Are central banks panicking?

The Fed's surprise intervention on the weekend of March 11-12 to try to stop the contagion linked to the SVB bankruptcy was not enough to stop the global run on bank deposits.

A single chart explains the current contagion: US banks are sitting on more than $700 billion of losses on their bond portfolios.

The losses are purely accounting, as these products are intended to be held until maturity. But the regional bank failures are forcing the realization of these losses and pose an immediate concern for the insolvency of these institutions.

The cause of these bankruptcies is a run on deposits, which began last week and is now spreading to the entire regional banking sector in the United States, as well as to the most fragile banks such as Credit Suisse.

This bank run is primarily linked to an arbitrage movement.

How is it that a risk so simple to understand (and repeated many times in my bulletins) was not taken seriously by a larger number of "analysts"? Out of the 19 professionals covering SVB, 11 were buying the stock, 6 were in a "hold" position... It was not until March 10, a few hours before the bank's failure, that 2 analysts out of 19 reacted and changed their recommendation to sell the stock!

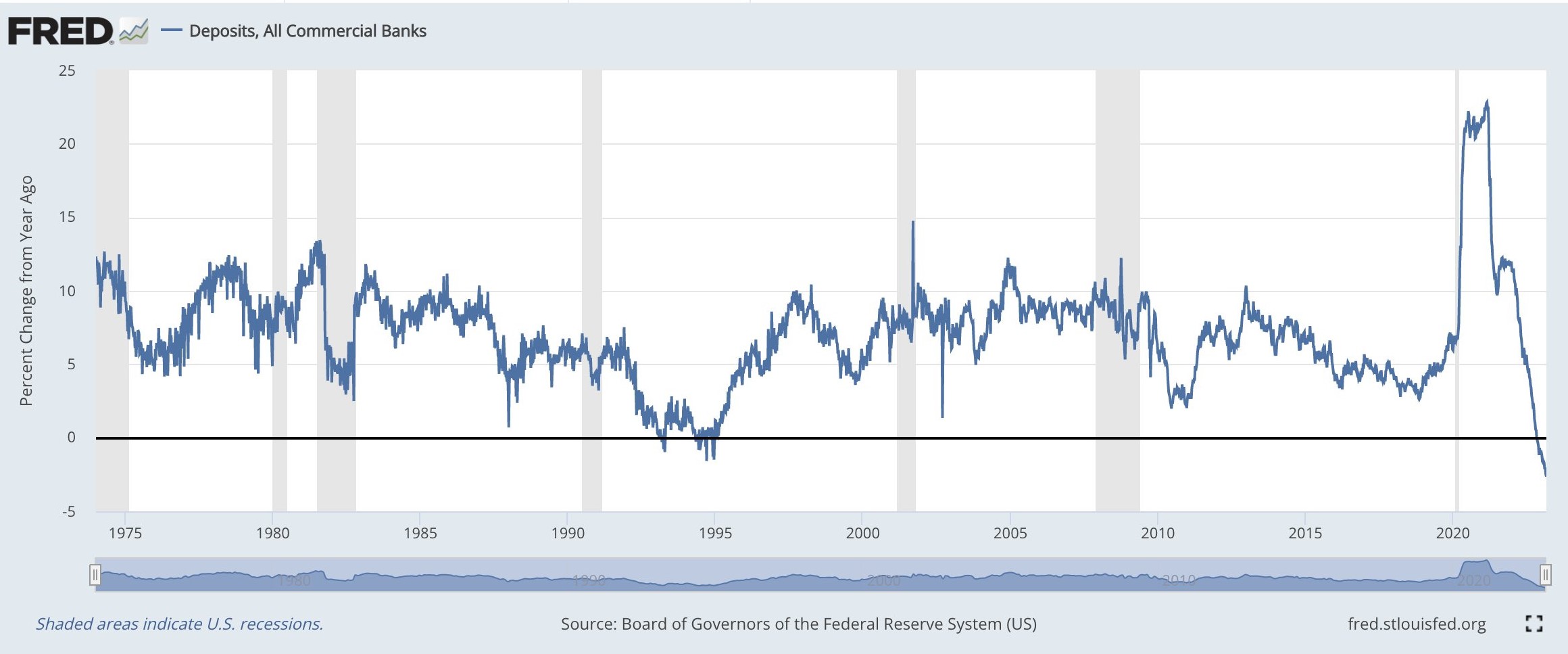

Yet the origin of the run on deposits is quite simple:

Deposits at U.S. commercial banks have been falling sharply since the rate on Treasury bills (T-Bills) rose above 5%. Not only do these securities pay more than money tied up in a bank account, but they are also safer in the event of a run on the bank's deposits. The banking panic has accelerated the movement; more and more Americans are converting their cash reserves held in their accounts and buying T-Bills or ETFs linked to these short-term bonds which now provide better protection.

The movement accelerated and self-fueled the run on deposits, forcing banks to sell their assets: the losses on the products they were supposed to hold until their term were effectively realized.

To prevent these losses from being realized and contaminating the balance sheets of other banks, the Fed implemented a new tool following the SVB bankruptcy: the BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program), which aims to open lines of credit to banks to prevent them from selling their securities at a loss. The Fed lends liquidity to banks up to the face value of their bonds. Instead of having to sell at a loss, banks can now borrow from the Fed the equivalent of the amount of their bond securities at purchase value, not market value. Even though the securities physically remain on the banks' balance sheets, the cash advance is made against the value at the time the securities were purchased. These very flexible terms even provide an opportunity for new liquidity for the banks. JP Morgan has even estimated that this program could provide more than $2 trillion in additional liquidity! The Fed has already given up on balance sheet reduction, adding de facto $300 billion just for this first SVB rescue operation. Once again, monetary tightening is coming to an end much faster than expected. Since 2008, promises of a sustained reduction in the Fed's balance sheet have never been fulfilled.

Another decision taken in the panic following the SVB bankruptcy: the FDIC has decided to guarantee all deposits held by SVB clients, including amounts exceeding the famous $250,000 limit. A special fund will be set up and it will be financed by mandatory contributions from all banks. In other words, the SVB's losses are socialized through the entire US banking industry. SVB's customers will ultimately lose less money than those of other banks who will have to pay them back.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, who had predicted that she would not see another financial crisis in her lifetime, even had to promise an unlimited FDIC guarantee on deposits to try to stop the ongoing bank run. The FDIC is capitalized to the tune of $128 billion, whereas the amount of deposits in commercial banks in the United States is $17.6 trillion!

All bank deposits will be safeguarded, but banks that do not pose a systemic risk will not. With this type of selective measure, regional banks that are not "too big to fail" are now at risk. This decision could push the clients of these banks to transfer their assets to institutions more protected by the Fed. The most fragile institutions could be tempted to become "Too big to fail" in order to obtain the Fed's holy protection. How to become "Too big to fail"? All you have to do is become the counterparty of a large banking institution and make it bear the solvency risk in case of a collapse.

This counterparty risk caused a second weekend of panic, one week after the SVB bankruptcy.

March 19 will remain an historic day in Switzerland.

Credit Suisse was bought by UBS in an operation that has not finished making our Swiss neighbors react.

The shareholders of Credit Suisse were devastated by the operation: the bank was bought at -62.5% compared to its closing price of last Friday, while the share had already devalued by almost -95% in just a few months. The chart of the Credit Suisse debacle will long remain in the memory of banking investors:

More surprisingly, holders of AT1 bonds (Additional Tier 1 bonds) were also liquidated in the operation. However, these bonds are purchased for just this type of resale scenario. Equity holders are supposed to be liquidated first before this class of investors can be touched. And the decision to harm these investors now puts the entire AT1 bond market at risk. The loss to investors amounts to $16 billion, a record amount since the inception of the market.

The Swiss National Bank (SNB) is providing a CHF 100 billion hedge to the new UBS entity that will inherit the Credit Suisse portfolio.

To ensure sufficient liquidity, the SNB will have access to currency swaps set up by the Fed on an emergency basis.

That same Sunday, March 19, Jerome Powell tried to reassure the public about the stability of the financial system. A few hours later, the Fed introduced massive new measures to help central banks to exchange dollars for their currencies in an emergency.

Why such an emergency? Why such amounts? What is it about Credit Suisse's balance sheet and off-balance sheet accounts that is generating such panic?

Yet Credit Suisse has passed the tests imposed by the new banking solvency constraints...

Paradoxically, in order to avoid the contagion of banking risk, the authorities are now forced not to reveal the true exposure of Credit Suisse at the time of its takeover by UBS. To keep confidence, one must lie!

And to top it all off, the Swiss authorities have decided to force the issue! UBS shareholders will not be consulted. A special law will ignore their voice and they will have to assume the risk transferred to the institution in which they are shareholders!

The cost of the contract (CDS) allowing to insure against the risk of default of UBS explodes with this repurchase, proof that the risk is from now on transferred directly to the bank:

It is incredible to see such an operation taking place in Switzerland! But apparently, without this power move, the entire financial system was in danger of faltering.

The last two weeks have demonstrated in a factual way several monetary aspects that I regularly address in my bulletins:

- Bank deposits are being converted into unsecured securities using significant leverage.

- These securities are currently creating losses on banks' balance sheets, which materialize when the bank is in trouble and has to sell these securities before they mature.

- The FDIC is not sufficiently capitalized to insure all deposits. Promises made to bank customers only bind those who believe in them.

- Banks are forced to lie to keep their customers and avoid a bank run.

- Customers must have confidence in their bank's ability to avoid a bank run. To help them, they can count on analysts, but most of them did not see the banking crisis coming. They can count on new regulations, but these have been unable to prevent this new crisis.

- The whole financial system and the value of fiat money are ultimately held together by trust.

- Confidence in the functioning of the system presupposes that the customer continues to trust his bank, which is forced to lie to him.

It is primarily this last, illogical point that rationally drives investors to physical gold held outside the banking system.

The confidence of the system is based on an inconsistency that has no practical resolution.

Gold is the best way to protect against the contagion of banking risk.

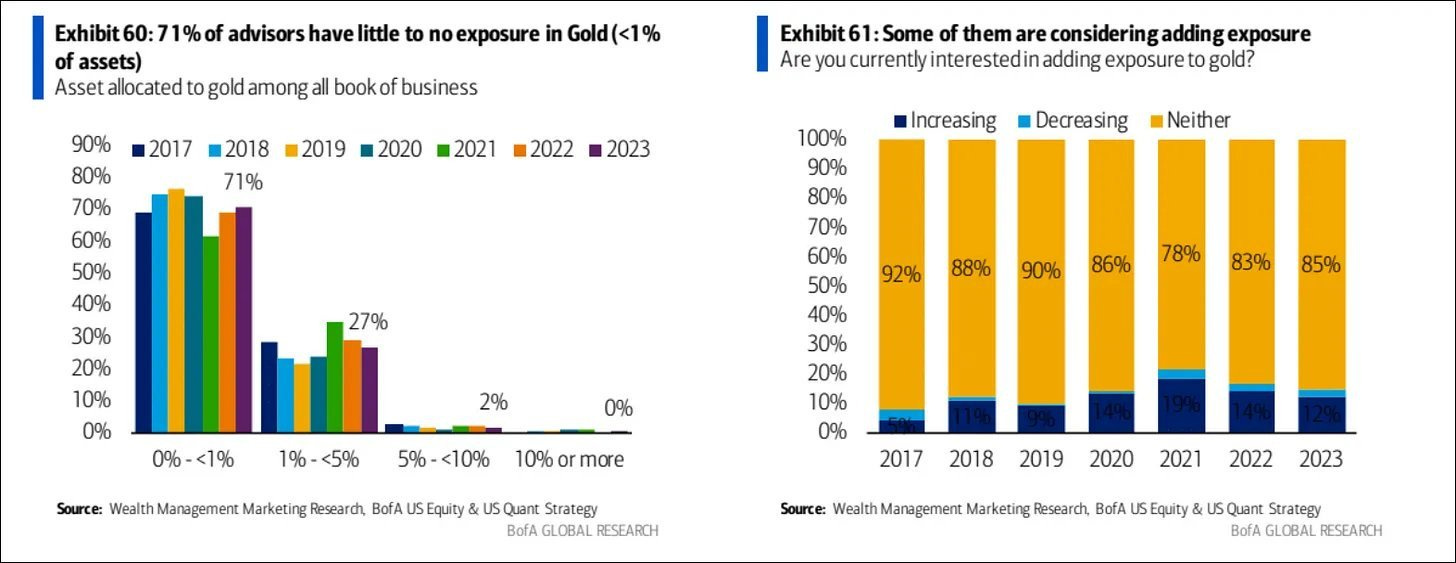

Very few institutions have understood this very clear fact.

Gold is very rarely included in investment portfolios. And when institutions are exposed to gold, it is almost entirely through certificates and ETFs and not in physical metal. More worrying: investment plans do not yet include the purchase of physical gold!

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.