Weiss, Colin R. (2025). "Official Reserve Revaluations: The International Experience," FEDS Notes — Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, August 1, 2025,

With public debt at high levels, some governments have begun to explore financing additional expenditures without raising taxes while also not increasing public debt outstanding. One possibility is using proceeds from valuation gains on gold reserves, as has been floated in the U.S. and Belgium recently.[1] For the U.S., this would involve revaluing the government's 261.5 million troy ounces in gold reserves — the largest gold reserves globally — from a statutory price of $42.22 per troy ounce to current market prices, which stand around $3300 per troy ounce.[2]

This note reviews the rare cases when countries used proceeds from valuation gains on gold and foreign exchange reserves. Over the past 30 years, only five countries have done so — Germany, Italy, Lebanon, Curacao and Saint Martin, and South Africa. What motivated the governments in these countries to use the proceeds from valuation changes in their official reserves? How were the revaluations implemented, and what were the outcomes? Revaluation proceeds have been either used by the central bank, as in the cases of Italy and Curacao and Saint Martin, or by the central government, as in South Africa, Lebanon, and Germany.

Central banks have used revaluation proceeds to offset operating losses and maintain net profits or minimize reported net losses.[3] In Italy, revaluation proceeds covered a one-off loss for the conversion of a specific bond the Banca d'Italia owned. In Curacao and Saint Martin, the proceeds covered losses generated by a fall in interest income from holding relatively lower-yielding securities than previous years and realized valuation losses as the central bank rebalanced its portfolio. The use of revaluation proceeds temporarily boosted profits for both central banks, but, in Curacao and Saint Martin, the use was paired with other measures to genera additional income on a sustained basis.

Central governments have drawn on revaluation proceeds to retire existing debts, often in exceptional fiscal circumstances. While reducing the debt stock using revaluation proceeds improves the fiscal situation at the margin, drawing on revaluation proceeds may not address larger structural challenges. For example, Lebanon's debt-to-GDP ratio continued to increase even after revaluation proceeds were used to retire some existing debts.

Background: Accounting for gold and foreign exchange reserves on central bank balance sheets

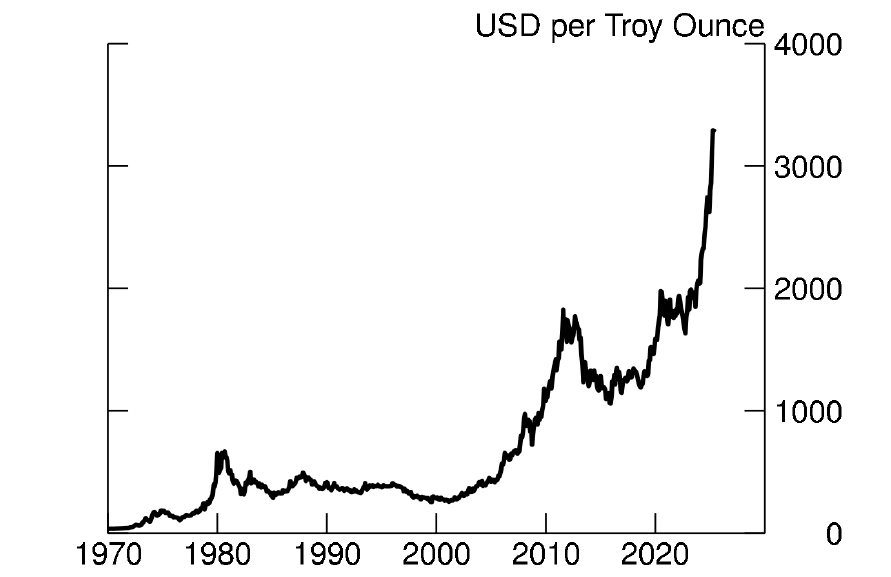

Central banks use a wide range of accounting procedures to value the gold holdings on their balance sheets (Sullivan, 2018). Some value their gold reserves at their historic cost; others report it at current market prices. When central banks report their holdings at current market prices (fair value), the unrealized profits or losses from valuation changes are recorded in "revaluation accounts" on the liability side of the balance sheet. Practically, the unrealized valuation changes in gold reserves are often reported together with the valuation changes on foreign exchange reserves in a single entry on the balance sheet. When gold is valued at historic cost (or modified historic cost), gold reserves can be revalued at market prices (or values closer to market prices) to generate revenues. When all official reserves are valued at market prices the unrealized valuation changes recorded in the revaluation account can be shifted to other parts of the balance sheet to generate funds, as discussed in more detail below. Drawing on valuation changes in gold as a funding source is particularly salient because most gold reserves globally were acquired prior to 1990, and as shown in Figure 1, gold prices have climbed substantially since then.

Figure 1. Price of Gold: 1970-2025

Source: Bloomberg

The cases discussed below include several different methods for creating funds, and I outline these methods using stylized balance sheet here. Importantly, in all cases, the quantity of international reserves remains unchanged during the use of revaluation proceeds (either in terms of the physical amount of gold or the par value of assets held as reserves). The first broad category is gold reserves valued at historic cost with the central government as the end user. Table 1a shows the initial change to the central bank's balance sheet due to a revaluation that increases the reported value of the gold reserves by X: assets increase by X due to the change in the valuation, while liabilities also increase by X as the valuation gains are distributed to the central government's account with the central bank. As the central government uses these new funds, the composition of the liability increase will shift from the government's account to commercial bank reserves held at the central bank (not shown in the figure).

The second broad category of revaluation transfer is when gold reserves are reported at fair value and funds listed in revaluation accounts are transferred to the central government. Table 1b shows this example for a transfer of size Y. In this case, only the composition of the central bank's liabilities changes: revaluation accounts decrease by Y while the central government's account with the central bank increases by Y. Again, as with the previous case, commercial bank reserves at the central bank will increase as the central government uses its new funds.

The final broad case of revaluation transfer present in the international experience is when gold reserves are reported at fair value and the central bank uses its revaluation accounts to offset other operating losses. Table 1c displays this for a transfer of size Z. Here, as with the previous example where revaluation accounts were used, only the composition of the central bank's liabilities changes. In this case revaluation accounts decrease by Z while net profits increase by Z.[4]

Table 1. Stylized Examples of Revaluation Transfers on Central Bank Balance Sheets

| Assets | Liabilities | |

|---|---|---|

| a. Reserves valued at historic cost, use by central government | Gold Reserve +X | Central government account +X |

| b. Reserves valued at fair value, use by central government | Gold revaluation account -Y | |

| Central Government Account +Y | ||

| c. Reserves valued at fair value, use by central bank | Gold Revaluation Account -Z | |

| Net profit +Z |

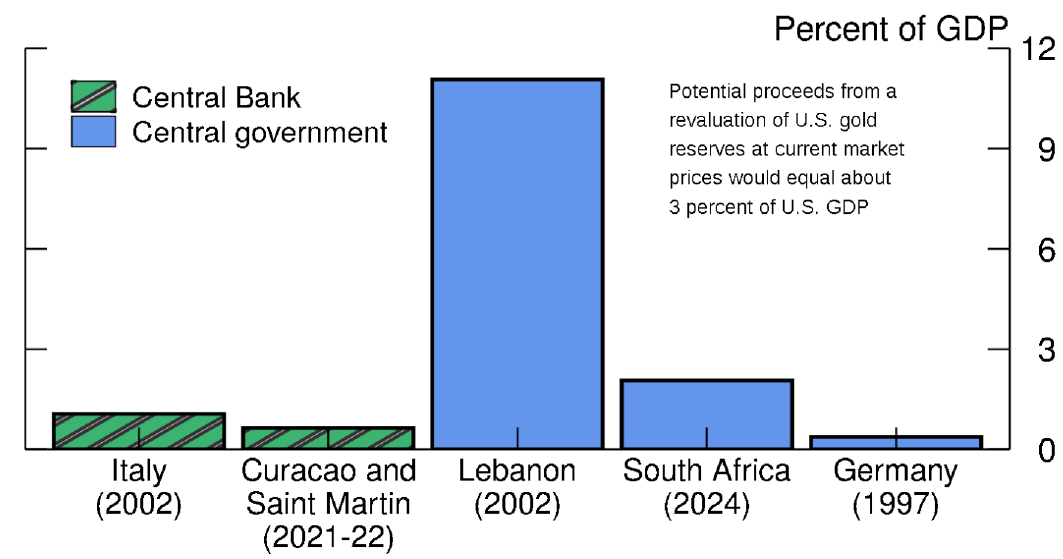

Figure 2 plots the funds created by using revaluation proceeds as a share of GDP in the year the funds were for each of the five international examples. The bars shaded green denote cases where the end-user was the central bank, while bars shaded blue mark examples where the central government sought to use revaluation proceeds. Except for the German case, the transfers when the end-user is the central government are larger than the proceeds used by the central bank. For comparison, the inset note reports the potential revaluation amount as a share of GDP for the U.S.

Figure 2. International Reserve Revaluation Proceeds

Note: Potential proceeds from a revaluation of U.S. gold reserves at current market prices would equal about 3 percent of U.S. GDP. Bar color distinguishes end-user of revaluation proceeds.

Sources: World Bank World Development Indicators and country central bank annual reports.

International use of revaluation proceeds by central banks

-

Curacao and Saint Martin

The most recent uses of revaluation account proceeds by a central bank occurred in 2021 and 2022, when the Central Bank of Curacao and Saint Martin (CBCS) engaged in simultaneous sale and purchase transactions involving $55 million of their gold reserves ($5 million in 2021 and $50 million in 2022). The central bank's annual reports for these years state that they sold portions of their gold reserves and then immediately repurchased this gold at the same price to convert unrealized valuation gains on their gold reserves into realized profits (CBCS, 2022, 2023). Essentially, after the transactions, the CBCS could book these now-realized profits as income and use them to offset other losses incurred by the bank in these years.[5] In 2021, generating this additional income allowed the CBCS to cover the remaining losses entirely out of retained earnings from 2019, while the 2022 revaluation-related transaction allowed the bank to turn a small net profit that year.

Combined, these two simultaneous sale purchase transactions involved about 8 percent of the CBCS's gold reserves and was equivalent to about 0.6 percent of the 2021 and 2022 GDP of Curacao and Saint Martin, relatively modest amounts compared to other cases and leaving plenty of scope for additional use of the revaluation accounts. However, in 2023, the CBCS did not conduct a simultaneous purchase and sale transaction involving its gold reserves to offset continued operating losses. Instead, it sold just over 1 percent of its gold reserves to generate income to offset losses and shifted its official reserves portfolio more towards assets that have higher yields to "increase…interest income" (CBCS, 2024). That move was thus part of a larger rebalancing of the CBCS's official reserves portfolio towards assets that generated significant interest income. Therefore, the CBCS appears to have used its gold revaluation accounts to help offset losses in a couple years, but it relied on other means to generate a more permanent increase in income.

-

Italy

In 2002, the Banca d'Italia transferred €13 billion from its gold revaluation accounts, or about half of the 2001 value of the account, to help cover losses (Banca d'Italia, 2003). Specifically, the proceeds were used to cover some of the losses resulting from a conversion of nonmarketable sovereign bonds held by the Bank of Italy to marketable debt securities to comply with EC Treaty regulations. The nonmarketable bonds had originally been issued to the Banca d'Italia in 1993 to replace the Treasury's overdraft account at the bank. The transfer was equal in size to about 1 percent of Italy's 2002 GDP, as seen in Figure 2, placing it on the smaller side of the examples discussed in this note. Against the objective of helping the central bank avoiding reporting overall net losses, this use of revaluation account proceeds, was quite successful, as the Banca d'Italia reported a small net profit in 2002.

International use of revaluation proceeds by central governments for fiscal policy

-

South Africa

The most recent use of unrealized profits from revaluations in international reserves by a central government occurred in South Africa in 2024. Specifically, the National Treasury and the South African Reserve Bank agreed to use R150 billion of the valuation gains recorded in the "Gold and Foreign Exchange Contingency Reserve Account" (about 30 percent of the total valuation gains in the account) between 2024 and 2027 to "reduce borrowing, and consequently the growth in debt-service costs" (National Treasury, 2024). This transfer is equivalent to about 2 percent of South Africa's 2023 GDP, which, as shown in Figure 2, places it in the middle of the size distribution of the actual and proposed revaluations studied in this note.

At the time of the proposal, South Africa's fiscal situation was far from ideal. Like other countries in recent years, South Africa's government debt-to-GDP ratio surged at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Debt servicing costs, which were already higher than in many EMEs, rose somewhat in 2022 and 2023 to just over 20 percent of government revenues with the global rise in interest rates (National Treasury, 2024).[6] The International Monetary Fund's (IMF) Article IV staff report for South Africa in 2024 highlighted challenges of declining GDP per capita (with real GDP growing less than 1 percent in 2024) and high unemployment alongside the difficult fiscal situation (IMF, 2025). Still, South Africa's fiscal circumstances are less exceptional than other cases discussed below, which involved violations of fiscal rules or recent multilateral debt reductions.

Given that South Africa's use of revaluation account proceeds is ongoing, it is too soon to assess whether their use helped place fiscal policy on a more sustainable path. Future interest expenses may fall not only due to the reduction in government debt outstanding but also because the reduction in the debt stock induces a fall in South Africa's borrowing costs. Indeed, long-term bond yields in South Africa fell on the day the plan to transfer revaluation proceeds to the National Treasury was announced, though it is harder to know whether the plan caused yields to fall on a more s (Goko-Petzer, 2024).[7] At the same time, as noted by McCauley (2024), the National Treasury's savings from lower interest expenses will likely be offset at least to some degree by increased interest expenses for the South African Reserve Bank. Therefore, the total savings to the consolidated South African public sector (central government and central bank) is far more uncertain.

-

Lebanon

Lebanon transferred some of its unrealized profits on its gold and foreign exchange reserves to the central government to retire $1.8 billion of treasury bills in December 2002 (IMF, 2003). This was equivalent to around 11 percent of Lebanon's 2002 GDP, making it the largest use of revaluation proceeds (in domestic GDP terms), as reflected in Figure 2.

The relatively large size of this operation likely reflected Lebanon's extremely difficult fiscal situation at the time. Lebanon had incurred substantial debts to rebuild its physical infrastructure following the end of the Lebanese Civil War in 1990, and the interest costs of this debt consumed 91 percent of government revenues by 1997 (Hausmann et al., 2023). The use of the revaluation accounts in December 2002 followed a meeting in November 2002 organized by the French government to mobilize international financial assistance to aid the Lebanese government.

Despite the international aid, the retirement of some government debt through funds transferred from gold revaluation accounts, and a swing of the primary fiscal balance into surplus territory, Lebanon's debt to GDP ratio continued to increase after 2002, and further financial assistance and fiscal restructuring was agreed upon in 2007.[8] Some of the debt retirement that occurred in 2007 resulted from additional use of the gold revaluation accounts, as the IMF's 2009 Article IV consultation report for Lebanon lists exceptional government financing in 2007 equal to 6.3 percent of GDP that consisted of debt cancellation and gold revaluation (IMF, 2009). Overall, the Lebanese experience again highlights that while gold revaluations can provide funds for the government, their ability to offset larger structural challenges can be limited.

-

Germany

In 1997, German chancellor Helmut Kohl and finance minister Theo Waigel proposed a revaluation of Germany's gold and foreign exchange reserves with DM20 billion of the revaluation gains to be used to offset deficits elsewhere in the German budget.[9] The Bundesbank valued its gold reserves at historic purchase prices that were significantly below the prevailing market prices in 1997. With the creation of the euro and the European Central Bank (ECB) in 1999, the Bundesbank was going to have transfer at least a portion of its international reserves to the ECB. The ECB planned to value reserves at current market prices and record valuation changes in its own revaluation account, meaning that the Bundesbank would be transferring unrealized valuation gains on its gold reserves to the ECB.

Kohl and Waigel planned to revalue the reserves prior to their transfer to the ECB and use a portion of the revaluation gains equivalent to 0.5 percent of 1997 German GDP to help shore up the government's budget (Duckenfield, 1998).[10] Specifically, the plan would have this portion of the revaluation gains repay some of the debt of the Redemption Fund for Inherited Liabilities, a special fund created by the federal government to help assume some of the local East German government debts upon unification. This part of the government balance sheet would then show a surplus that would offset deficits elsewhere in the German fiscal balance.

The use of some of the revaluation gains to reduce the German budget deficit was necessary because the level of the deficit was projected to violate the threshold set in the Maastricht treaty. Germany's economy had weakened towards the end of 1996, and the German government had needed to borrow more than it originally planned in the first half of 1997. Violating the Maastricht treaty at the time would have been particularly perilous because it would have both endangered Germany's ability to join the European Monetary Union and undermined the credibility of the deficit targets set in the Maastricht treaty that the German government had pushed for (Duckenfield, 1998).[11]

Opposition to the revaluation plan emerged from both the Bundesbank and the broader German public, and their opposition highlights that revaluations may not be viewed as prudent fiscal management. The Bundesbank argued that the plan violated the independence of the central bank and that meeting the Maastricht criteria through revaluation "would not do justice to these requirements" (Bundesbank, 1997). Leading German newspapers ran editorials opposing the revaluation on the grounds that such a use of revaluation proceeds would encourage other governments to violate the Maastricht criteria (Duckenfield, 1998). Eventually, a compromise was reached where German official reserves were revalued in 1997, but the funds that were originally to be used to cover the fiscal deficit in 1997 were not distributed until 1998.[12] In addition, the Bundesbank's 1997 annual report indicates that only DM13 billion of revaluation gains were distributed in 1998, smaller than the initially proposed amount (Bundesbank, 1998a). In the end, the German fiscal deficit in 1997 satisfied the Maastricht criteria even without the proceeds from the revaluation.

References

Archer, David and Paul Moser-Boeh (2013). "Central Bank Finances," BIS Papers No. 71.

Banca d'Italia (2003). Abridged Report for the Year 2002 (PDF). Rome: Banca d'Italia, November.

Bundesbank (1997). "Revaluation of Gold and Foreign Exchange Reserves," Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report (June): 5-8.

Bundesbank (1998a). Annual Report 1997 (PDF). Frankfurt: Deutsche Bundesbank, May.

Bundesbank (1998b). "Public Finance," Deutsche Bundesbank Monthly Report (September): 32-44.

Central Bank of Curacao and Saint Martin (2022). Annual Report 2021 (PDF). Willemstad/Philipsburg: Central Bank of Curacao and Saint Martin, May, .

Central Bank of Curacao and Saint Martin (2023). Annual Report 2022 (PDF). Willemstad/Philipsburg: Central Bank of Curacao and Saint Martin, December.

Central Bank of Curacao and Saint Martin (2024). Annual Report 2023 (PDF). Willemstad/Philipsburg: Central Bank of Curacao and Saint Martin, December.

Duckenfield, Mark (1998). "The Goldkrieg: Revaluing the Bundesbank's Reserves and the Politics of EMU," Program for the Study of Germany and Europe Working Paper Series 8.6.

Goko-Petzer, Colleen (2024). "South African Rand Jumps as Nation Taps Reserves for Debt," Bloomberg, February 21.

Hausmann, Ricardo, Ugo Panizza, Carmen Reinhart, Douglas Barrios, Clement Brenot, Jesus Daboin Pacheco, Clemens Graf von Luckner, Frank Muci, and Lucila Venturi (2023). "Towards a Sustainable Recovery for Lebanon's Economy," CID Faculty Working Paper No. 439.

International Monetary Fund (2003). "IMF Concludes 2002 Article IV Consultation with Lebanon," Public Information Notice No. 03/36.

International Monetary Fund (2009). "Lebanon: Staff Report for the 2009 Article IV Consultation and Assessment of Performance Under the Program Supported by Emergency Post-Conflict Assistance," IMF Country Report No. 09/131.

International Monetary Fund (2025). "South Africa: Staff Report for the 2024 Article IV Consultation," IMF Country Report No. 25/28.

National Treasury (2024). Budget Review 2024 (PDF). Pretoria: National Treasury, February.

McCauley, Robert N. (2024). "Shifting South African Public Sector Borrowing," Global Economic Governance Initiative Working Paper 062.

Sullivan, Kenneth (2018). "Working Towards a Common Accounting Framework for Gold," World Gold Council Discussion Paper 16/06.

1. In the U.S., the idea has come up in the context of helping to establish a strategic bitcoin reserve or a sovereign wealth fund, and the use of revaluation proceeds was proposed in recent legislation by Senator Lummis (https://www.congress.gov/bill/118th-congress/senate-bill/4912/text). In Belgium, the press reported the governing coalition was considering financing additional spending partly through monetization of some of the National Bank of Belgium's gold reserves, with the National Bank of Belgium commenting on the idea in a recent press release (https://www.nbb.be/doc/ts/enterprise/press/2025/cp20250319en.pdf).

2. The U.S.'s gold reserves are owned by the Treasury department, and the statutory price was set by a 1973 law (the text of the law can be found at https://www.congress.gov/93/statute/STATUTE-87/STATUTE-87-Pg352.pdf.)

3. For a useful discussion of central bank finances in general, see Archer and Moser-Boehm (2013).

4. The specific reporting of this increase in net profits depends on the exact institutional arrangement for the distribution of the central bank's net profits. I abstract from this detail in my stylized example.

5. The CBCS's annual reports for these years note that income fell largely due to realized losses (or reduced valuation gains) on its investments from the global rise in interest rates while expenses increased due to rising interest rates (CBCS, 2022, 2023).

6. The National Treasury's 2024 budget review shows that South Africa's debt servicing costs are above the 75th percentile in a sample of 75 non-oil exporting emerging market economies (National Treasury, 2024).

7. The rand appreciated and South African CDS spreads fell following the announcement as well.

8. Interest payments over this period, while substantially lower than they were prior to 2002, remained above the primary surplus, so overall debts continued to grow (Hausmann et al., 2023).

9. Although addressing the fiscal deficit was the primary motivation for the revaluation at that specific time, less than half of the proceeds from the revaluation would have been used for this purpose. In addition, DM25 billion would have been placed in a special reserve fund for exchange rate stabilization, and just under DM5 billion were to be used to increase the Bundesbank's capital position (Duckenfield, 1998).

10. Overall revaluation proceeds would have totaled 1.4 percent of 1997 German GDP.

11. The Maastricht Treaty required countries to have a fiscal deficit of 3 percent of GDP or less in the year before they adopted the euro.

12. Specifically, the funds were distributed in the second quarter of 1998, and the Bundesbank's September 1998 report on public finance seems to imply that there was likely to be a slight reduction in German fiscal deficits in 1998 compared to 1997 even excluding the revaluation proceeds (Bundesbank, 1998b).

Original source: Federal Reserve

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.