In the past few weeks, a coordinated barrage of hawkish comments by central bankers of some of the world’s most advanced economies have pushed long-term bond yields higher, clearly weighing on gold prices. At the annual ECB forum in Sintra, Portugal, President Mario Draghi talked about a strengthening and broadening global recovery supporting nascent reflationary forces in Europe. At the same conference, Bank of England Governor Mark Carney mentioned the possibility of removing monetary stimulus soon if economic slack continues to lessen, and Governor Stephen Poloz’s comments about absorbing excess capacity in Canada were perceived as a hint of an imminent rate hike, delivered last week.

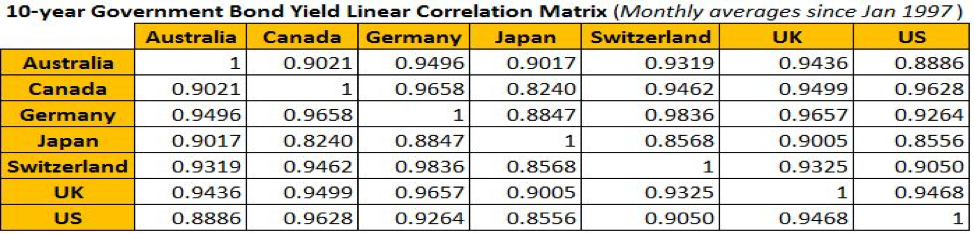

The concerted effort, driven by growing optimism about a global economic recovery taking root after a lackluster 2016, had a noticeable impact on fixed income with global bond prices dropping markedly. Yields on 10-year government bonds have risen sharply in the US, Canada, Germany, the UK, Switzerland and even Australia, where the central bank has conspicuously refrained from joining the hawkish chorus. To be fair, this is of course due to the very high correlation among the advanced economy government bond markets as shown in the matrix below.

Sources: FRED, RBA, BoC, ECB, BoJ, SNB, BoE, author's calculations

The sell-off in fixed income has been such that gold prices came off despite an initial drop in the US dollar, temporarily trouncing the long-term negative correlation between the currency and the precious metal. To some observers the move has been reminiscent of the “taper tantrum” in 2013, when former Chairman Bernanke’s announcement that the Federal Reserve would begin to reduce its purchases of Treasury bonds as part of its quantitative easing program drove 10-year Treasury yields from 1.66% in May to nearly 3% by September.

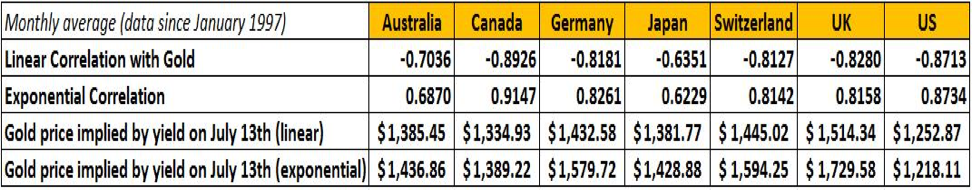

Despite the recent sell-off in bonds however, with the notable exception of 10-year US Treasuries global yields at present levels still appear consistent with significantly higher gold prices. To be sure this may simply be an indication that global bond yields are too low, especially when compared to US Treasuries, although by the same token narrowing interest rate differentials would suggest a weaker US dollar ahead. The table below shows linear and exponential correlations of the precious metal with a number of the major global bonds over the last 20 years, as well as the gold prices in USD that would be consistent with current yield levels. In particular, note that 10-year Canadian government bond yields, which are more highly correlated to gold than even US Treasuries, suggest gold prices at almost $1390 on an exponential basis. In the UK, although certainly highly influenced by even greater uncertainty emanating from Brexit, current levels on 10-year gilts are consistent with prices in USD at almost $1730.

Sources: FRED, RBA, BoC, ECB, BoJ, SNB, BoE, author's calculations

Going forward, a crucial question for gold is the extent to which the major central banks will be able to achieve a much sought-after but likely elusive “normalization” of monetary policy. In other words, pressure on gold prices stemming from higher yields will depend on where interest rates eventually peak in this tightening cycle and whether those levels approach those of previous cycles. Ultimately this will almost assuredly depend on the strength and sustainability of the nascent recovery and the reflationary forces allegedly underway, as well as whether growth and inflation rates return to what would be considered to be more “normal” levels.

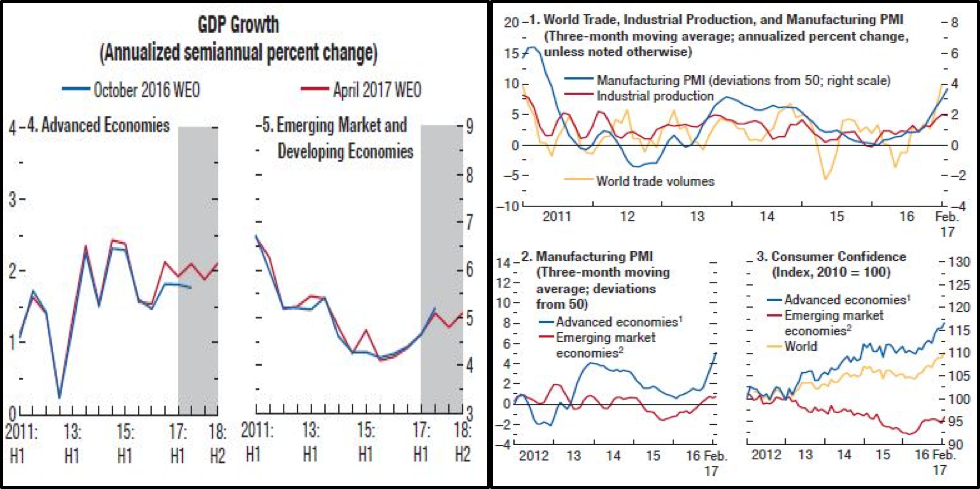

There have certainly been signs of improvement in global economic data since last year, when growth in emerging markets was the weakest since 2009. Global growth has clearly picked up since the first half of 2016 on the back of a recovery in global trade, manufacturing and investments, in advanced and emerging markets alike, as the IMF highlighted in its April meeting. Leading economic indicators from the OECD also point to further progress over the next 6 to 9 months for most major economies, giving further impetus for central banks to begin removing extraordinary monetary policy accommodation.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook April 2017

The legendary Sir John Templeton is credited with saying that “the four most expensive words in the English language are “this time it’s different””, a maxim that is well-known to most investors and usually associated with bubbles and generally preceding crises. However, unconventional monetary policy following the global financial crisis, including record levels of debt and negative interest rates in a number of countries, has led to terra incognita for the global economy and financial markets. The Fed is expected to start what is likely to be a long process of balance sheet reduction by the end of the year, while the ECB is likely to begin tapering of its quantitative easing next year. The “normalization” of monetary policy, while plausible, may turn out to be a misnomer or even a pipe dream without much stronger growth and inflation. In their absence, long-term global bond yields are likely to remain below what would be considered “normal” in previous cycles, and downward pressure on gold prices likely weaker than in the past.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.