The prices of gold and silver have just set new historical records, confirming the monetary regime shift that major global investors have been anticipating for several years.

Gold has just crossed the symbolic threshold of $4,000 per ounce for the first time in its history, while silver is approaching $50, its highest level since January 1980. This double record is not simply a speculative episode: it marks a real change in the monetary regime that is rapidly accelerating.

What is at stake today goes beyond the simple rise in the price of a metal: it is the questioning of an entire system.

The biggest names in global asset management – Jeffrey Gundlach (DoubleLine), Paul Tudor Jones (Tudor Investments), Ray Dalio (formerly of Bridgewater), and Ken Griffin (Citadel) – share the same diagnosis: the dollar is structurally depreciating, fiat currencies are losing credibility, and inflation is here to stay.

As Ken Griffin, founder of Citadel, points out, inflation remains stubborn, the dollar has just recorded its biggest half-yearly fall in half a century, and gold is breaking record after record. Capital is gradually turning away from assets based on trust and redeploying towards those based on tangible value – gold, silver, or even rare digital assets.

In other words, confidence is shifting away from assets based on promise and returning to assets based on substance.

The paradigm shift is impossible to ignore: the era of the 60/40 portfolio is coming to an end, and the next decade could see the biggest rotation of capital in a generation. Gundlach is already talking about gold at over $4,000, silver at $50, and, as in the 1970s, this is probably just the beginning. Remember that between 1977 and 1979, silver increased eightfold – without even counting the leverage effect of mining companies.

But while gold and silver symbolize the loss of confidence in currency, copper now embodies its physical limit. The United States is about to run out of the very metal that allows... electricity to flow. Every hyperscale data center, every charging station, every “green” transmission line relies on miles of copper. And yet, current policy is blocking the public infrastructure that consumes the most, without reducing demand.

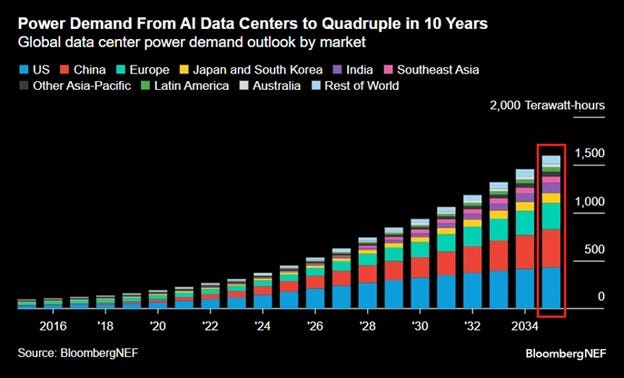

The major energy modernization plan launched under Biden – more than 3,000 high-voltage line and interregional corridor projects – has just been frozen by the Trump administration in the name of “budget streamlining.” As a result, the government is pulling out, but the private sector is stepping in on an unprecedented scale. The giants of cloud computing, semiconductors, and AI are rebuilding their own power grids. A single hyperscale campus requires between 30,000 and 50,000 tons of copper. In other words, the more the public grid disintegrates, the more metal the private sector consumes.

The paradox is complete: reducing the federal scope increases private demand. Every megawatt not distributed by the government must be rebuilt at private expense, with miles of cables, transformers, and redundancy – all made of copper.

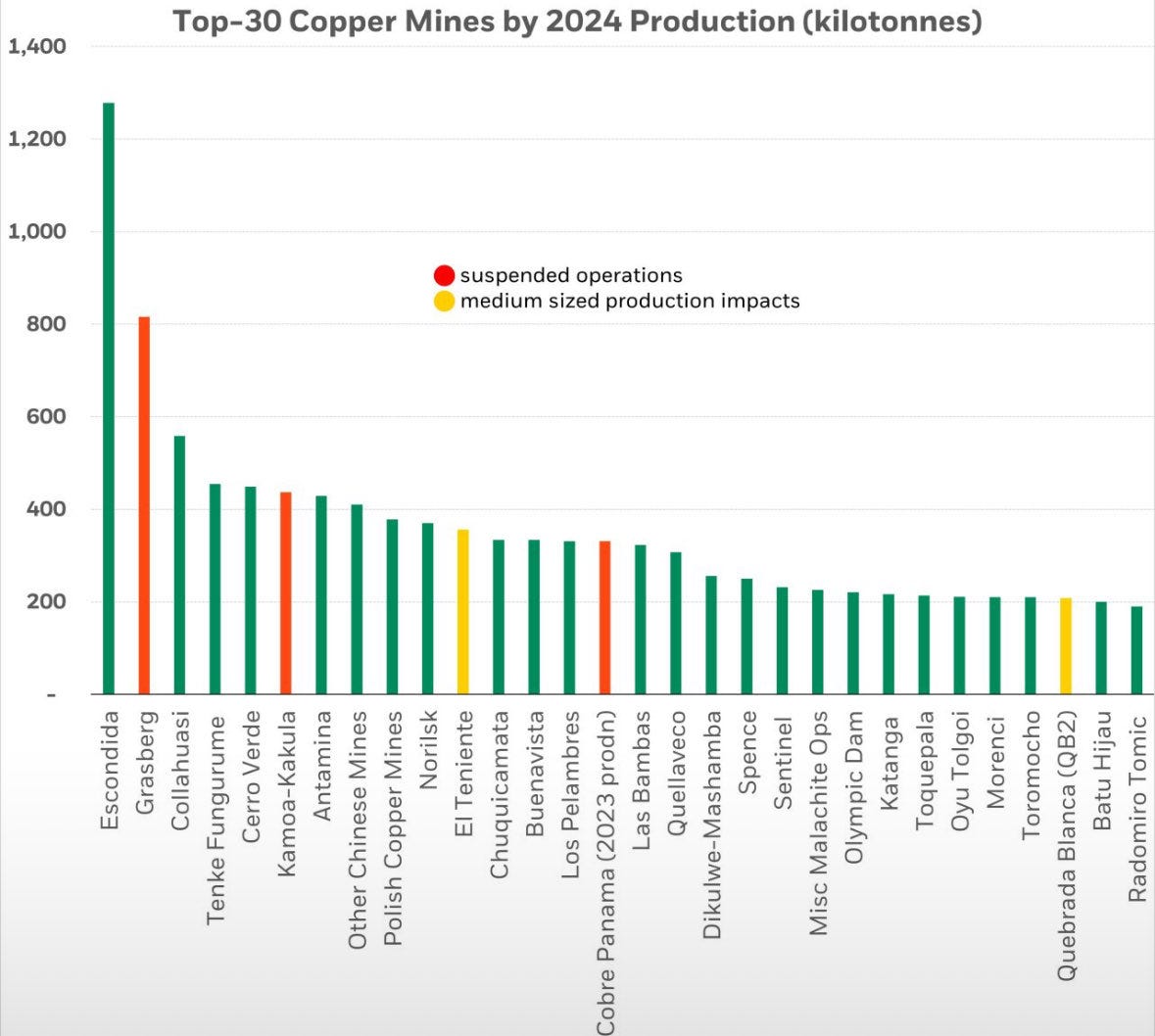

Meanwhile, global production is declining and the major historical deposits are running out:

Chuquicamata and Escondida in Chile are experiencing steadily declining grades; Cobre Panamá has been shut down since the Panamanian Supreme Court ordered its closure; and Grasberg in Indonesia was hit this summer by a major landslide in the underground area, causing the temporary shutdown of part of its operations. The accident damaged several tunnels and ore transport infrastructure, reducing Freeport-McMoRan's processing capacity by nearly 3% of global supply. Safety and restoration work is expected to continue until the end of the fourth quarter of 2025, delaying a return to full production and putting further pressure on global copper stocks. In the DRC, Kamoa-Kakula has seen part of its production suspended following seismic activity, while in Peru, Las Bambas and Constancia remain exposed to chronic social tensions. In Chile, Codelco, the pillar of national production, is accumulating delays and cost overruns at El Teniente and Radomiro Tomic, with a decline of nearly 10% in its production in 2025.

The problem is not limited to geology or social climate: it is structural. The cost of opening a new mine has tripled in ten years, the time it takes to obtain permits often exceeds ten to twelve years, and the majors – BHP, Rio Tinto, Glencore, Freeport – now prefer to buy advanced projects rather than finance them. The global pipeline of new capacity is therefore desperately empty: less than three million tons of new capacity by 2030, while demand is growing twice as fast.

Another constraint, more discreet but just as decisive, adds to that of copper: rare earths.

China has just announced a series of extraterritorial restrictions on the export of technologies and products related to the production, refining, recycling, and manufacturing of rare earth magnets. Most importantly, any company using these materials to manufacture semiconductors of 14 nm or less will have to obtain specific authorization from Beijing. In other words, China now has an implicit veto over the entire global semiconductor chain – from TSMC to ASML, whose lithography systems depend on these materials for their magnets and lasers.

The scope of these controls is extraterritorial: any product containing more than 0.1% Chinese-sourced rare earths will require a license before it can be re-exported. This is an almost exact mirror image of the US restrictions imposed on China on semiconductors – but this time, Beijing holds the key to the essential metal.

So, just as America seeks to relocate its technology production and build a sovereign digital infrastructure, two bottlenecks are closing in: copper and rare earths. The former limits the physical capacity to transport energy; the latter limits the technological capacity to transform it.

Gold and silver are breaking records because monetary confidence is crumbling. Copper and rare earths are becoming essential because physical constraints are setting in.

And it will be difficult, if not impossible, to rebuild the US AI infrastructure without copper... and without rare earths.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.