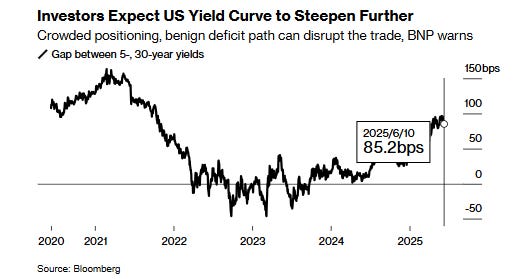

Guneet Dhingra, head of US Rates Strategy at BNP Paribas points out this week that market positioning in favor of a steepening yield curve — i.e. a rise in long-term yields relative to short-term rates — has reached its highest level in at least ten years. In his view, this shows that this bet is now too "overcrowded", increasing the risk of a reversal.

A "crowded" steepener trade means that a large number of investors are betting on a widening of the spread between long and short rates — in other words, on a steepening of the yield curve.

In practical terms, this translates into a yield curve trading strategy in which investors:

- Buy long-term bonds (e.g. 10- or 30-year bonds), to take advantage of a possible rise in yields, and therefore a fall in price if they expect a gradual rise, or conversely if they expect a bull steepener (when long rates fall less quickly than short rates);

- Sell short-term bonds (e.g. 2-year bonds), because they anticipate that short rates will fall more quickly or that their current yield is too high.

This type of trade can also be made with interest-rate swaps or futures on different maturities, but the idea remains the same: to bet on a faster rise — or slower fall — in long rates relative to short rates.

The fact that this trade is "crowded" means that too many people have already set it up. As a result, the scope for further gains is limited — and, above all, if the momentum were to reverse, all these investors could make a massive reverse move, triggering particularly severe market fluctuations.

It's a bit like a crowded theater: as long as everything's going well, the atmosphere remains calm. But at the slightest warning, everyone rushes for the exit — and that's when things can get seriously out of hand.

The analyst therefore recommends an options-based strategy, designed to take advantage of outperformance in long-maturity interest rates in a context of generalized rate easing. He points out, however, that fiscal concerns remain, even if much of the skepticism seems already priced in.

Dhingra sums up the situation wryly: "Steepeners are big, but not as beautiful. " This type of position could well become the next pain trade — a gamble that ends up backfiring on the majority of investors who are heavily exposed to it — given current market conditions.

The main risk for those massively positioned in a steepener trade lies in a scenario where the curve does not steepen as anticipated, or even flattens. This can happen in two ways:

- Long rates fall faster than short rates: this often happens in a context of economic slowdown, flight to safety, or if markets anticipate strong long-term monetary easing (a lasting reduction in key interest rates). In such cases, the price of long bonds rises sharply, penalizing those who have sold them as part of a steepener.

- Short rates remain high or even rise again, while long rates stabilize or fall only slightly: this can happen if the Fed remains hawkish for longer than expected, for example because inflation persists or the job market remains tight. In this case, short rates do not fall, and the yield curve remains flat or flattens further.

In both scenarios, the market's steepening bet fails, and as many investors are leveraged into the market, losses can be very rapid and substantial.

In other words: the more massive and credit-financed the consensus, the more asymmetric the risk. And if the market disappoints this consensus, even slightly, the downturn can be brutal.

This is exactly what Dhingra calls a pain trade: a scenario that few anticipate, but which hurts those who have massively taken the same bet.

If the yield curve steepening bet reverses, it could have a significant impact on the gold price.

In a scenario where long rates fall rapidly — for fear of recession or a return to caution by central banks — gold would benefit. Falling real interest rates would make the metal more attractive, and rising risk aversion would reinforce its role as a safe-haven asset. Conversely, if short-term rates remain high or rise again, this could temporarily weigh on gold, due to higher opportunity costs and a possible strengthening of the dollar.

The real risk for the markets — and therefore a potential rebound driver for gold — would lie in a sudden withdrawal from bond market positions, linked to the high leverage on steepening trades. Such a jolt would send shockwaves through risky assets and, after any initial stress, gold would once again become a sought-after asset for its stability. In short, a sudden reversal in the steepener trade could rekindle gold's rise.

Gold continues to trade at historically high levels, supported by continued massive purchases of physical metal by central banks.

This dynamic of massive purchases by central banks, which began three years ago, has never really stopped. Unlike traditional investors, these institutions do not let short-term price fluctuations dictate their strategy. They don't "play" with gold: they accumulate it.

What guides their actions is not a speculative rationale, but a structural objective: to strengthen the solidity and sovereignty of their reserves by reducing their dependence on foreign currencies, particularly the US dollar. In other words, they aim to replace a growing proportion of their monetary reserves with physical gold, perceived as a universal, apolitical safe-haven, not subject to counterparty risks or sanctions.

These purchases are planned, regular and part of a long-term rationale. Whether gold is trading at $1,800, $2,400 or $3,000 an ounce, central banks continue to pursue their strategy, convinced of the geopolitical and monetary relevance of this accumulation. It is this consistency — far more than passing tensions or speculative movements — that today constitutes the gold market's most solid foundation.

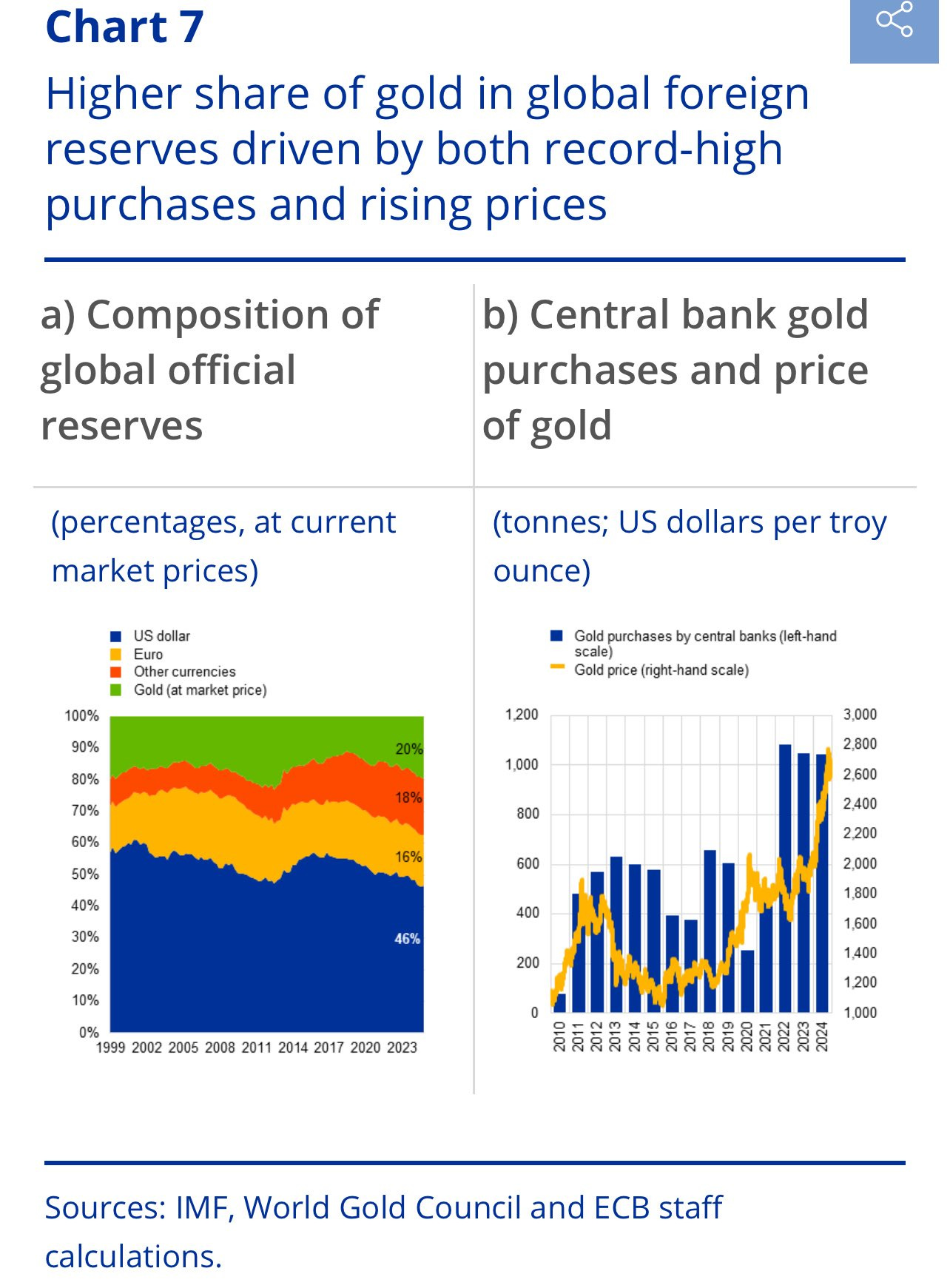

According to the European Central Bank (ECB), gold has now overtaken the euro to become the world's second most important reserve asset held by central banks, just behind the US dollar. This historic development is due both to a record increase in official gold purchases and to the soaring price of the precious metal.

By 2023, gold will account for 20% of the world's official reserves, compared with 16% for the euro. Only the US dollar remained ahead, with 46%. This shift marks a break in the architecture of international reserves. Long marginalized, gold is now once again playing a central role, driven by strategic purchasing policies pursued by central banks — particularly those of emerging economies or countries wishing to reduce their dependence on the dollar-dominated monetary system.

The graph on the right clearly illustrates this dynamic: since 2022, gold purchases by central banks have regularly exceeded 1,000 tons per year, a pace unprecedented in recent history.

At the same time, the price of gold has soared, nearing $3,000 an ounce, illustrating the convergence between institutional demand and a growing mistrust of fiat currencies.

Gold's rise to prominence is taking place against a tense geopolitical backdrop, where economic sanctions, bloc wars and financial instability are prompting more and more countries to turn to a non-political, liquid asset with no counterparty risk: physical gold.

In short, the ECB confirms what many analysts have been observing for the past three years: gold is no longer a simple safe-haven asset, but has once again become a central pillar of global monetary sovereignty.

According to Bloomberg, central banks are buying almost four times as much gold as they officially declare. This discrepancy suggests that many purchases are made discreetly, via alternative channels or with a deliberate delay in the publication of figures.

Behind this opacity lies a strategic intent: to accumulate gold without causing an immediate price surge, or drawing attention to a possible coordinated de-dollarization movement.

Central banks have been buying nearly four times more gold than what has been publicly disclosed, according to Bloomberg.

— Otavio (Tavi) Costa (@TaviCosta) June 4, 2025

A new gold rush is unfolding in real time. pic.twitter.com/Bzepx6LD0g

This concealment of purchases is taking place against a backdrop of geopolitical tension, marked by an erosion of confidence in the major fiat currencies — particularly the US dollar — in certain regions of the world. In this context, gold has regained a central role in the reserve strategy of central banks, as a bulwark against inflation, a hedge against the risk of sanctions, and a diversification tool outside the dollar-dominated monetary system.

The fact that these massive purchases are partly invisible in the official figures suggests that the real pressure on the gold market is much greater than it appears. If this reality were to be fully taken on board by investors, the gold price could experience another sharp surge, underpinned by far greater demand than the available data would suggest. This confirms that gold remains a pillar of long-term sovereign strategies, often conducted far from the spotlight.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.