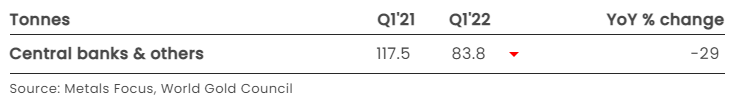

- Central bank gold demand in Q1 more than doubled q-o-q, but was 29% lower y-o-y

- Our survey findings show that central banks highly value gold’s performance during time of crisis

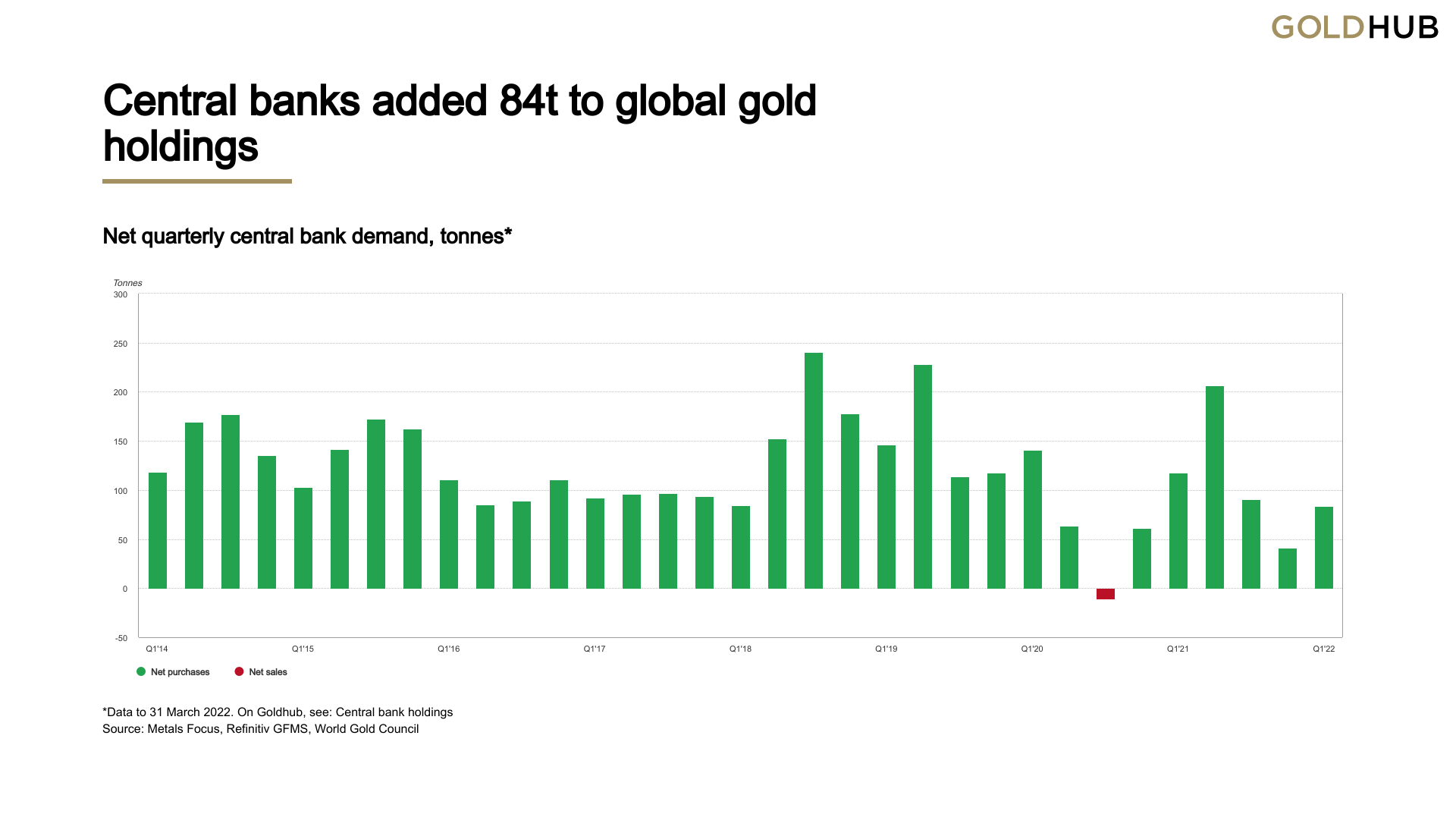

- At a country-level, both sizeable purchases and sales were seen during the quarter.

Global central bank gold reserves grew by a net 84t in Q1, 29% lower than in Q1 last year and driven primarily by a small number of sizeable transactions. During a turbulent quarter marked by geopolitical crises and surging inflation, central bank net demand for gold was somewhat muted, but nonetheless positive. This corresponds with the findings from our 2021 central bank survey: for the first time respondents highlighted gold’s performance during periods of crisis as the top reason to hold gold.

Sources: Metals Focus, Refinitiv GFMS, World Gold Council; Disclaimer

*Data to 31 March 2022. On Goldhub, see: Central bank holdings

Activity in the sector was dominated by a limited number of central banks with a few large transactions tipping the balance.

Egypt was the biggest buyer in Q1, reporting a 44t (+54%) increase in its gold reserves in February. This took total gold reserves to 125t, or 17% of total reserves which is on the higher end when compared to the country’s regional peers. For some time, Egypt has been adding gold from a domestic mine but usually in small increments. The Egyptian government has also been taking steps to ramp up domestic gold production in the long term. But the drop in FX reserves in January and February could mean that not all of the 44t came from domestic sources.

Turkey was the other major purchaser in the quarter, increasing its gold reserves by 37t. This pushed total gold reserves to over 430t, accounting for 28% of total reserves. India bought a further 6t during the quarter, taking gold reserves to 760t (8% of total reserves). Since it resumed buying in late 2017, the RBI has purchased over 200t, similar to the amount it bought from the IMF in 2009. Ireland was the other notable purchaser during Q1, adding a further 2t of gold on top of the nearly 4t bought in H2 last year. It also remains the only active buyer among developed market central banks, and while its monthly additions have been modest, it has increased overall reserves by 88%% since August.

In March, Ecuador also announced that it had added almost 3t to its reserves, sourcing the gold from small, local producers after it had been certified by an LBMA-accredited refiner. The statement also noted that holding gold “is of vital importance, since it represents a safe haven asset that appreciates in value during periods of uncertainty in the financial markets and geopolitical risks.”

In the same month, the Governor of the Central Bank of Ghana, Dr Ernest Addison, provided an update on the country’s Domestic Gold Purchase (DGP) programme. He announced that the bank had bought a total of 600kg since the programme launched in June 2021 with a target to increase its gold reserves from around 9t to over 17t by 2026. While the scale of buying remains modest, this is part of a recent trend among various central banks to buy domestically-mined gold using local currencies.

But arguably the biggest announcement during the quarter came in February, when the Central Bank of Russia (CBR) announced that it would resume buying gold from domestic producers following the imposition of international sanctions. The CBR suspended its gold purchases in 2020, since when its gold reserves have remained largely unchanged. Russia held just under 2,300t of gold (21% of total reserves) at the end of January, the last available data point at the time of writing. No indication was given on the scale of purchases but we will continue to monitor developments.

The majority of the sales in Q1 came from the gold-producing nations of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, at a time of rising gold prices. Kazakhstan was the largest seller during the quarter, decreasing its gold reserves by 34t to 368t. The central bank has traditionally bought from domestic sources, and it is not uncommon for those counties that buy locally-produced gold to swing between buying and selling. Uzbekistan reduced its gold reserves by 25t to 337t. While the decline is sizeable, this is not the first significant transaction from Uzbekistan in recent years. Active management of its gold reserves means changes are common, and even after its Q1 sale, gold reserves still account for 60% of total reserves.

Poland sold just over 2t during the quarter, taking gold reserves to 229t (9% of total reserves). While the central bank has been purchasing gold for strategic reasons, and recently announced its intention to buy 100t this year, its gold reserves are, at least in part, actively managed. Qatar (5t), Philippines (3t), Mongolia (2t), and Germany (1t) – the latter likely related to coin-minting – were also notable sellers during Q1.

Sources: IMF IFS, Respective central banks, World Gold Council; Disclaimer

*Data to 31 March 2022. Note: chart includes only purchases/sales of 0.5t or above. On Goldhub, see: Central bank holdings

Looking ahead, gold might attract further interest as a diversifier as central banks seek to reduce exposure to risk amid heightened uncertainty. Our expectation stands for central banks to remain net purchasers for 2022; however, slower economic growth and rising inflation may restrain central bank gold demand in the short term.

Original source: World Gold Council

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.