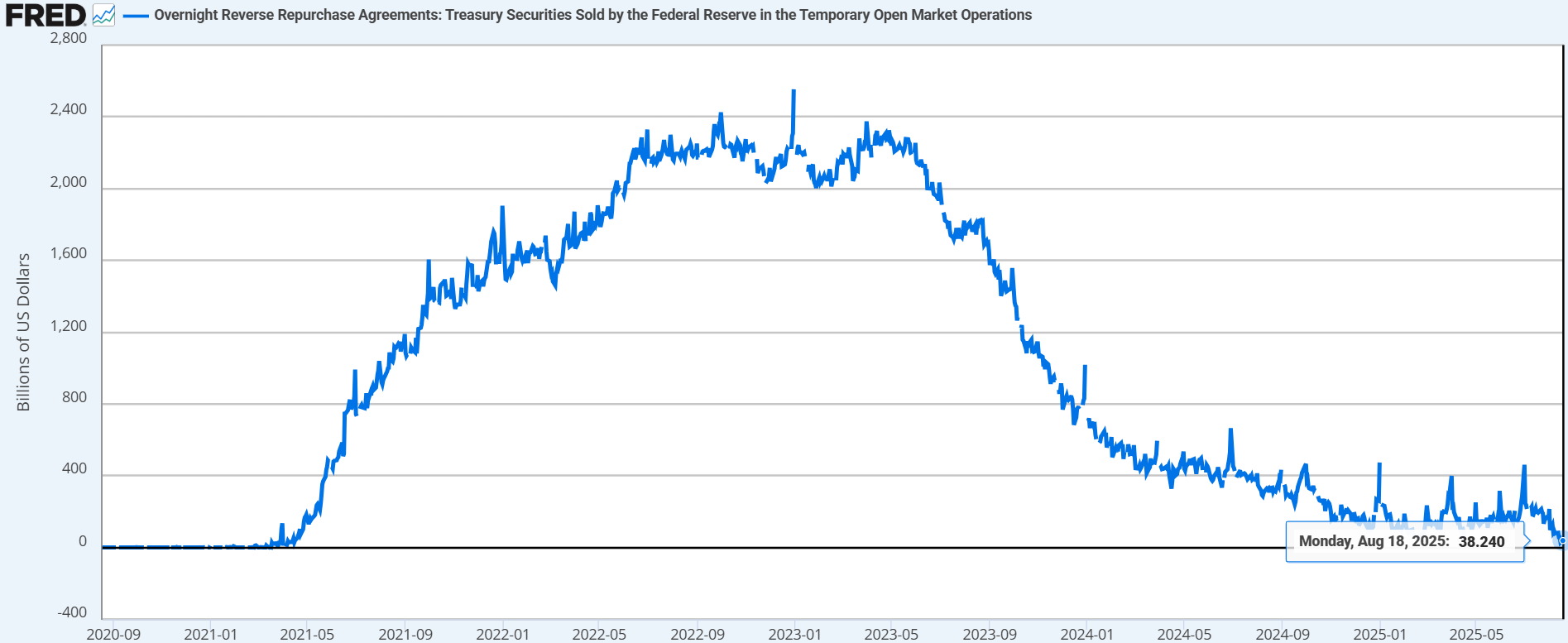

For several years, the US economy has been operating with a huge liquidity safety cushion: the Fed's famous Reverse Repo Facility (RRP). This was a kind of reservoir where money market funds placed their excess cash each night. At its peak in 2022, there was more than $2.5 trillion stored in this reservoir! This allowed the Fed to reduce its balance sheet (quantitative tightening) and the Treasury to issue massive amounts of debt without triggering an immediate crisis: all it had to do was draw on this reserve.

But that cushion is now empty. The RRP has fallen to around $38 billion, which is practically nothing.

In concrete terms, this means that there is no longer any cushion to absorb the US government's financing needs. From now on, every new dollar of debt issued by the Treasury or every dollar sucked up by the Fed through its QT will compete directly with the financing needs of banks, investment funds, and investors. In other words, the system has lost its “safety valve.”

This is precisely where the risk lies: as long as the RRP was full, it was possible to believe that liquidity was infinite and that the markets could absorb any volume of issuance. But with this valve exhausted, the system is exposed to tensions. We find ourselves in a situation similar to 2019, when the repo market froze within hours, or to 2007, when the funding markets froze. From now on, any shock can turn into a systemic liquidity crisis, because there is no longer any hidden buffer.

And yet, at the same time, credit markets are sending a completely contradictory signal. Investment grade credit spreads – that is, the yield premium that investors demand for holding debt from solid companies rather than Treasury bonds – have fallen to 0.73%, their lowest level since... 1998.

In short, investors are behaving as if the highest-rated US companies were almost as safe as the government, and as if there were no risk of default.

How can this paradox be explained? On the one hand, the excess liquidity that allowed all shocks to be smoothed out has disappeared. On the other hand, the market is acting as if this liquidity were still there, continuing to buy corporate credit without demanding a risk premium. This apparent strength of the system is partly an illusion. Banks hold mountains of bonds purchased when rates were much lower. With rates rising, the market value of these bonds has fallen sharply. Normally, this should appear in their accounts as losses. But an accounting trick allows them to hide these losses: by classifying these bonds as hold-to-maturity (HTM), they do not have to value them at market price. As long as they claim to hold them until maturity, these losses remain invisible on their balance sheets.

As a result, on paper, everything looks under control. Solvency ratios are stable, balance sheets appear robust, and investors may be under the impression that the banking system is in much better health than it actually is. But this robustness is artificial. If a bank is forced to sell some of its HTM assets to raise cash – for example, in the event of a liquidity stress – then the latent losses become real, immediately and on a massive scale.

This is exactly what happened with the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in 2023: supposedly “safe” bonds had to be liquidated, and hidden losses suddenly came to light, triggering a domino effect. In other words, as long as confidence holds and banks don't need to sell, the illusion works. But the day liquidity tightens, this facade of solidity can collapse very quickly.

The famous safety cushion is now empty. In concrete terms, this means that each new Treasury auction acts like a giant vacuum cleaner for liquidity: investors must mobilize immediate cash to buy the bonds issued, which dries up the system in the short term.

One might think that “fiscal QE” – i.e., deficit-financed public spending – offsets this phenomenon by injecting money into the real economy. But in reality, much of this money is used primarily to repay existing debt and plug deficit gaps. The net liquidity that actually returns to the system is therefore much smaller. And, more importantly, it arrives with a time lag relative to the immediate cash outflows associated with frequent Treasury auctions.

It is this disconnect that makes the situation particularly dangerous. Financial players – banks, funds, brokers – need to find cash immediately to absorb the supply of debt. Without a cushion like the RRP, they are forced to sell other assets or reduce their positions urgently in order to refinance. This causes violent shocks: credit spreads widen suddenly, volatility rises and forced sales can follow, sometimes in rapid succession. History has shown in 2019 and 2008 how quickly these financing tensions can arise when liquidity runs out.

In short, we are at a turning point. Markets are behaving as if the liquidity party could last forever, even though the hidden reserve that supported it has disappeared. This is the liquidity paradox: bright red risk signals on the one hand, and a perception of maximum security on the other. And it is precisely this kind of configuration that paves the way for the most brutal reversals.

The buyback mechanism normally allows the US Treasury to provide some flexibility to the market by repurchasing old bonds and injecting cash back into the system. It is supposed to be a technical safety valve, a means of easing liquidity demand. But recently published figures tell a different story.

In the latest operation, investors offered nearly $29 billion worth of securities for sale back to the Treasury. In other words, banks and funds wanted to offload their bonds en masse and recoup cash. However, the Treasury only agreed to buy back $4 billion. This discrepancy is striking: it highlights how strong the demand for liquidity is, but also how much of it remains unmet.

This episode perfectly illustrates the current paradox. Fiscal QE, i.e., deficit spending and public spending, does bring a little cash into the system. But this money is quickly absorbed by massive debt auctions, which act as veritable liquidity vacuums. The few corrective mechanisms, such as buybacks, are too limited to restore balance, especially since the Reverse Repo (RRP) cushion is virtually empty.

In practice, this means that every new debt issue or monetary tightening measure by the Fed hits the financial system directly, with no buffer. The situation is reminiscent of the 2019 repo crisis and the 2007 ABCP crisis: as long as everything seems to be holding up, tensions remain invisible, but as soon as demand for liquidity exceeds the system's capacity to respond, the correction can be brutal. Widening spreads, funding freezes, rising volatility, and forced sales then become inevitable.

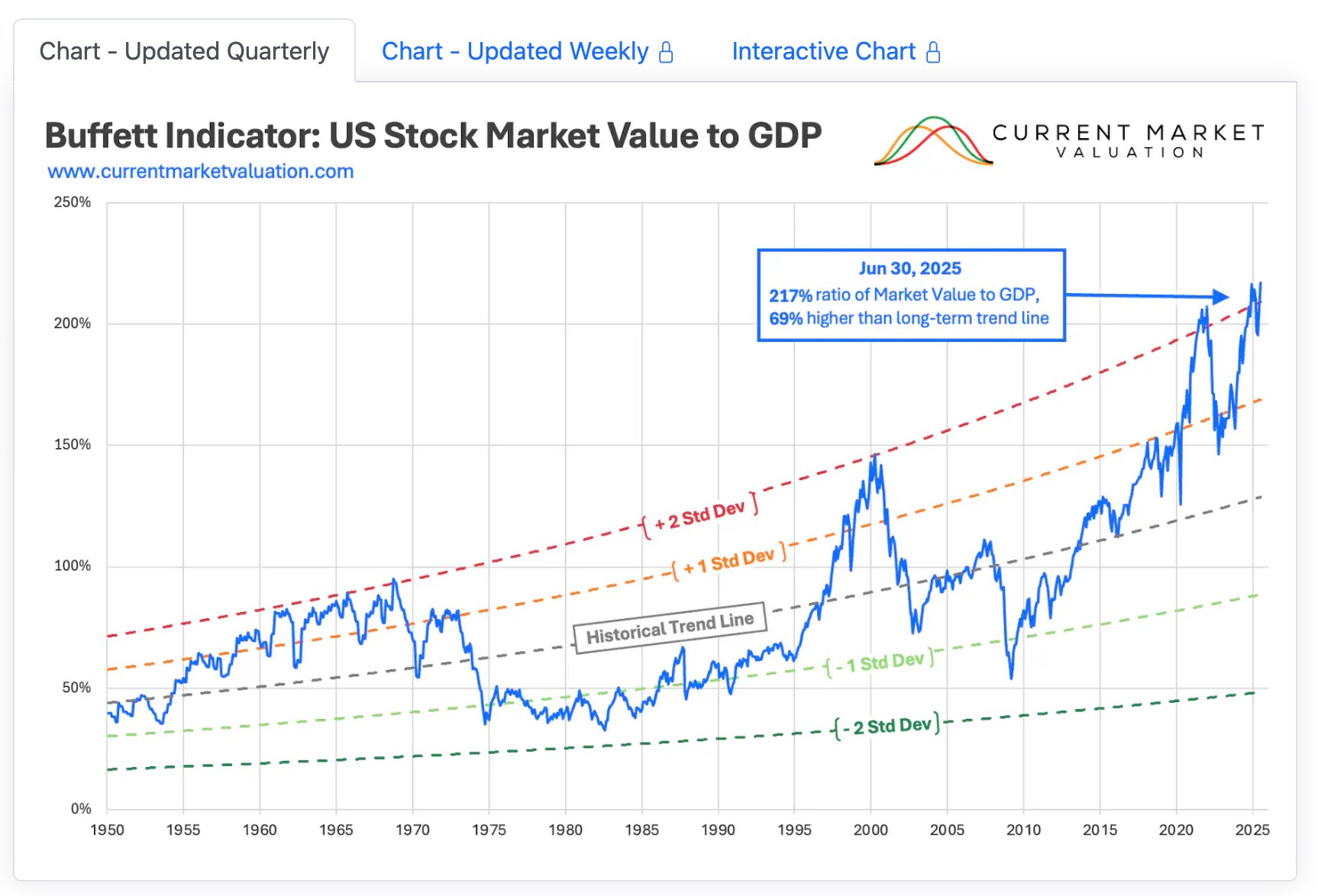

What makes liquidity risk even more dangerous today is that it is occurring in a market that is already completely disconnected from reality. By virtually every objective metric, the US stock market is not just expensive, it is wildly overvalued. Data compiled on June 30 by CurrentMarketValuation.com does not simply describe the market as “overvalued”; it describes it as “strongly overvalued” almost across the board, regardless of the model used.

Take the Buffett Indicator, which compares total market capitalization to US GDP. It is currently hovering around 200% of GDP, more than two standard deviations above its historical average. The only two times we have come close to such levels were at the peak of the internet bubble in 2000 and at the end of 2021. In both cases, investors suffered corrections of more than 40%.

In other words, we are reaching a point of maximum fragility: no more liquidity cushion (with the RRP almost depleted), a massive supply of Treasuries hitting the financing market head-on, and stock market valuations that leave no margin for safety. The slightest hiccup in liquidity could trigger a sudden downturn, because everything is already stretched to the limit.

We have already seen this recently. At the end of 2021, valuations were stratospheric, buoyed by abundant liquidity and zero rates. Signs of the market overheating were everywhere, but as long as the Fed kept pumping money into the machine, the market remained buoyant. Then, in early 2022, with the sudden shift toward monetary tightening, the wheels came off: indices fell 20% to 30%, and the most expensive stocks lost 60% or more.

Today, we find ourselves in an even more fragile situation. The difference is that the liquidity buffer that allowed the Fed to tighten the screws without immediate damage – the Reverse Repo Facility – is now almost empty. This means that even a limited funding shock could instantly spread through the markets. Extreme overvaluation is therefore compounded by structural vulnerability: there is no longer a safety net.

The parallel with 2000 and 2021 is illuminating: each time we reached these extreme valuation levels, the correction was deep and rapid. The difference in 2025 is that this risk of correction is compounded by real liquidity pressures. It is the combination of the two – overpriced markets and no cushion – that makes the current moment so explosive.

In this context, physical gold is regaining its status as a safe haven asset. When equity markets are trading at crazy valuations and the system's liquidity threatens to seize up, it remains a tangible asset with no counterparty risk, which central banks and private investors are quietly accumulating. It is no coincidence that, despite already high prices, central banks continue to buy gold at a steady pace: they clearly see that the dollar, the pillar of the system, is weakened by debt and liquidity tensions.

Gold does not generate yields, but in a world where financial assets are both expensive and vulnerable, it offers something even more valuable: the certainty of not being dependent on an overheated financial system, weakened by growing liquidity tensions, and which will probably need to resort to additional money creation to stabilize itself.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.