Current events have led to a flood of analyses in recent hours that are as spectacular as they are approximate: Japan is said to be triggering a “historic transfer of wealth,” the yen carry trade is about to explode, and a “Gilt moment” is brewing in the shadows. However, when we look at the markets, none of this holds water. The yen is not strengthening, quite the contrary; the USD/JPY remains abnormally high, proof that the dollar remains the scarce currency in a global liquidity crisis.

However, as long as the yen remains weak, there is no driver for unwinding carry trades. The very mechanics of the sensationalist argument collapse: unwinding carry trades requires a strong yen. We are far from that.

Alongside the persistent weakness of the yen, Japanese 20-year bonds are soaring – but they are no longer soaring for the same reasons as between 2021 and 2024.

The first phase of rising long-term interest rates in Japan, from 2021 to the end of 2023, was a classic reaction: Japan was emerging from a decade of zero inflation, prices were accelerating, and the BoJ was tentatively beginning to widen the YCC fluctuation bands. At the time, the steepening of the Japanese curve told a simple story: Japan was belatedly joining the global inflationary cycle. Investors naturally demanded higher returns for holding long-term bonds in an environment where inflation was no longer anecdotal.

But the current phase is entirely different. Since 2024, and more markedly since spring 2025, the rise in Japanese rates no longer reflects “persistent domestic inflation” or “Japan's awakening.” Today's rate rise is explained by a much more global mechanism: liquidity stress forcing foreign investors to liquidate long JGBs to raise dollars. European insurers, Asian pension funds, and global asset managers are selling 20-year bonds not because they doubt Japan, but because they need to pay margins, reduce their risky positions, or simply replenish their cash reserves. It is global refinancing needs that are driving the Japanese curve, not domestic conditions in Japan.

This shift is essential to understand: in 2021–2024, the rise in Japanese rates reflected economic normalization; in 2025, it reflects tension in the global monetary system. The previous phase was inflationary; the current phase is deflationary in spirit, as it speaks of a lack of cash, dollar scarcity, and forced adjustment of global leverage. The same movement – a rise in rates – tells two diametrically opposed stories depending on the period. It is precisely this ambiguity that many analysts fail to grasp, reading the current rise in JGBs as a “domestic” signal, when in fact it is a symptom of an entirely different balance sheet mechanism.

This latest rise in rates has been interpreted as either the end of the zero interest rate policy or the announcement of a historic domestic pivot. The reality is much simpler: foreign investors are short of dollars and are selling what is least useful as collateral, i.e., long-term JGBs. When you have to pay margins urgently, you liquidate paper that is useless in a cash crunch. The rise in Japanese 20-year and 30-year yields is therefore a symptom of global liquidity stress, not a sign of a Japanese monetary awakening. The budget plan announced for Friday adds a layer of term premium, but this is only a narrative catalyst: the real driver remains the hunt for dollars.

The comparison with British Gilts does not hold up either. In the UK in 2022, the crisis was essentially a leverage crisis: LDI pension funds exposed to five, six, or seven times their capital via interest rate derivatives, cascading margin calls, and an overwhelmed Bank of England forced to intervene amid the panic. Nothing, absolutely nothing in the Japanese structure resembles this. The BoJ holds half the market; Japanese banks, insurers, and pension funds almost never leverage JGBs; foreigners hold only a marginal fraction of the total stock. Nothing is scalable, nothing is left to the market, nothing can trigger a self-perpetuating spiral. Japanese long positions are being sold because that is what foreigners can sell, not because Japan is imploding.

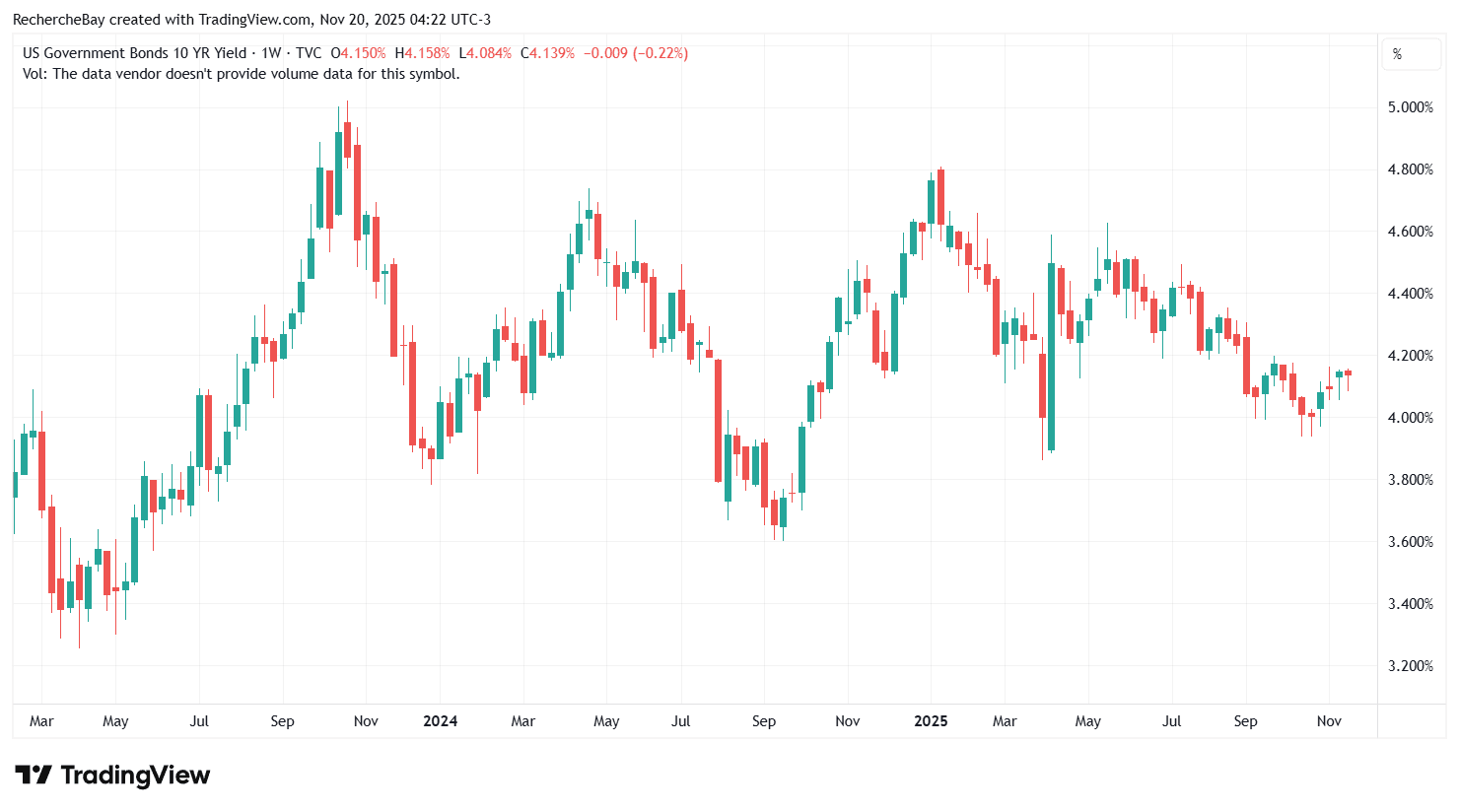

For all these reasons, we must not misjudge the crisis or its pace. We are not in a bond crisis. Not yet, anyway. If we were, US 10-year bonds would be on fire, Bunds would diverge, and the yield curves of developed countries would all become unanchored at the same time. None of this is happening.

The US 10-year remains stable:

What we are experiencing today is a cash crisis, a collateral crisis, where players are selling what they can, not what they want. It is a crisis of liquidity, not a crisis of confidence in sovereigns. The major bond crisis, the one that will call into question the sustainability of public debt, will undoubtedly come – but later, after the Fed's next intervention, when implicit monetization becomes impossible to hide. On that day, the debate will focus on the very credibility of governments. Today, we are in a state of emergency, focused on operations and short-term management.

Gold, meanwhile, is navigating this landscape perfectly and reacting in tandem with the rise in Japanese rates since 2023. This makes sense: when rates rise because liquidity disappears, gold captures the fear of the system; when rates rise because sovereign doubt sets in, gold captures the fear of solvency. The two trajectories – that of long-term JGBs and that of gold – tell the same story from two different angles: on the one hand, the fragility of governments, and on the other, the search for an asset without liabilities.

In a liquidity crisis, paper gold is automatically sold through ETFs to raise dollars, but at the same time, demand for physical gold increases, and we see the usual disconnect between the spot price, which consolidates, and physical premiums, which tighten. In liquidity crises, ETF flows never tell the whole truth about real demand.

One crucial point must be added: these episodes of liquidity stress have always offered unique opportunities to accumulate physical metal. The liquid market (ETFs, futures) is sold for the wrong reasons; physical metal is bought for the right ones. Premiums tighten, inventories fall, Asian imports pick up – all while giving the temporary illusion that “gold is falling.” Then, when the forced selling phase subsides, the spot price automatically catches up with the reality of physical demand.

In the current crisis, the price of gold is consolidating because of technical selling – not because of its strategic role.

In the next crisis, the sovereign debt crisis, it will rise for fundamental reasons. We are currently going through a phase where paper gold is being sold due to a lack of cash; next will come a phase where physical gold will be sought after due to a lack of confidence.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.