Since April, a large part of the market believed it had a simple strategy: to hedge against a market that had become too vertical, too dependent on AI, too expensive, and too unstable. Many managers and investors noted that valuations – particularly those of companies linked to artificial intelligence – were reaching worrying levels, even for those who were benefiting directly from them.

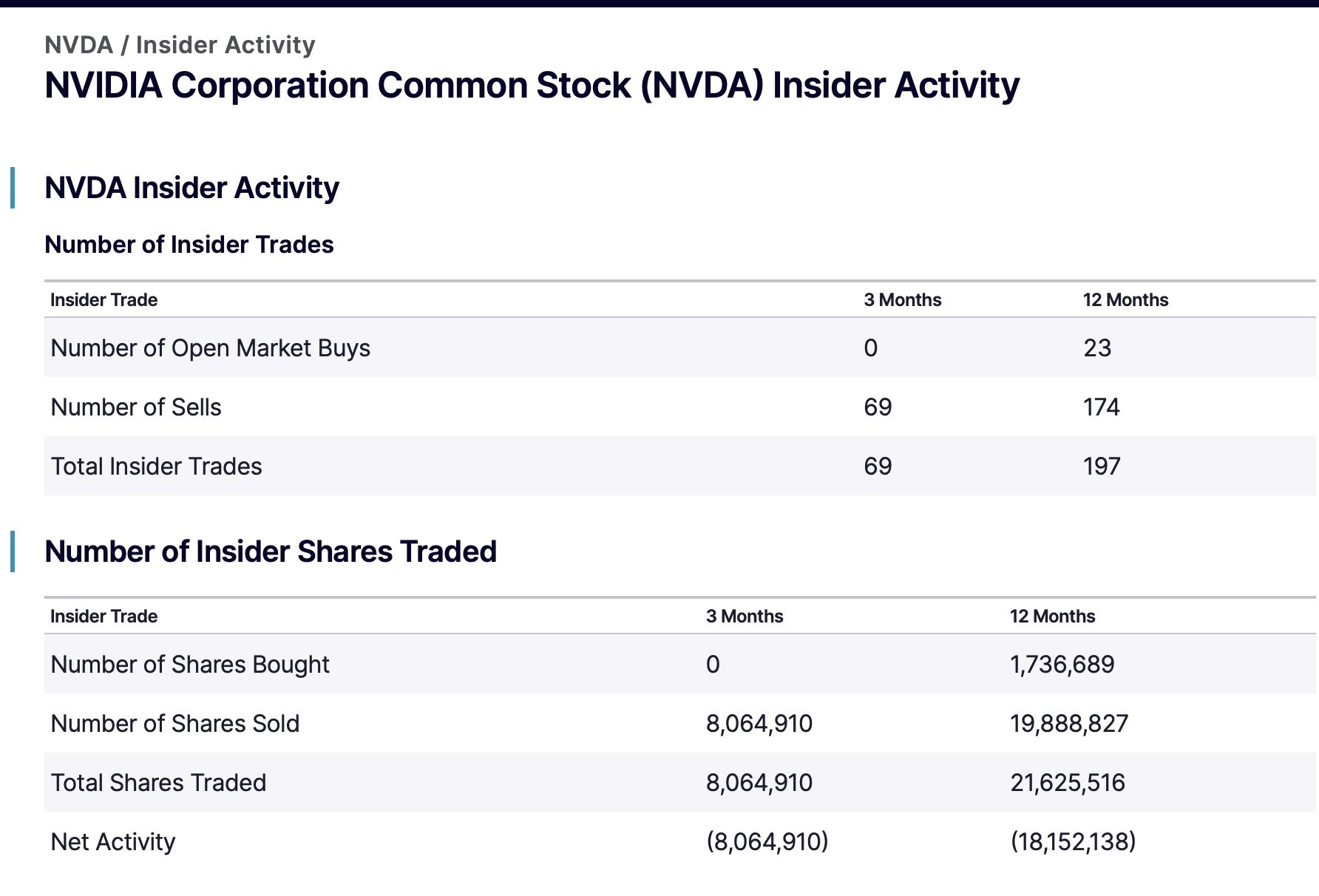

The example of NVIDIA is particularly telling: over the past three months, the company's executives and managers have carried out 69 share sales, compared with no purchases.

This represents more than eight million shares sold by those who know the company best. Over twelve months, nearly twenty million shares were sold, while purchases remained very marginal. When insiders – executives and senior managers – sell their own shares en masse, it generally reflects latent concern about the level of valuation. It's not that the company is of poor quality, but its stock price reflects such ambitious prospects that even those who know its inner workings prefer to lighten their positions.

In such a context, the need for hedging is real. Hedging means buying insurance to protect your portfolio against a correction. A classic hedge consists of buying put options, which generate a gain when the market falls.

An essential point that investors often overlook when purchasing a protective option is that an option reflects not only price expectations, but above all volatility expectations. When buying a put option for hedging purposes, one might think that one is simply purchasing a lottery ticket that will pay off if the index falls. In reality, this is only part of what you are paying for. Most of the price of a put corresponds to implied volatility, i.e., the level of future fear that the market anticipates. The higher the implied volatility, the more expensive the cost of protection, even if the index does not move. It's a bit like taking out home insurance in the middle of hurricane season: the house is no more fragile, but the price of insurance skyrockets because everyone is looking to hedge at the same time.

In today's markets, implied volatility has remained high for several months, largely because the index is highly concentrated and everyone perceives a form of structural instability. Thus, every time an investor buys a put option, they are not only betting on a market decline: above all, they are paying a high premium just for the right to bet. This initial cost can represent 70%, 80%, and sometimes 90% of the option's final value. As long as the market does not correct sharply, implied volatility disintegrates – this is the famous theta – and the put loses value, even if the fundamental situation has not changed.

This is a reality that many have forgotten: a put option is not an automatic winner when the market declines. Its price depends largely on volatility expectations, and a simple easing of this implied volatility can wipe out its value in seconds – even if the market itself has not rebounded. In other words, people paid for two things: theoretical protection in the event of a decline and insurance against volatility itself. And it is this second component – implied volatility – that has been methodically destroyed by the market's microstructure. This explains why almost all of the protection purchased since April has been wiped out: not only did the market not fall enough, but more importantly, implied volatility collapsed just when the insurance should have started to gain value.

The result is paradoxical but essential to understand: investors were right to seek protection, as extreme valuations and massive insider selling fully justified it. But the instruments they used were invalidated by volatility dynamics. They paid dearly for an invisible component – implied volatility – that was destroyed before their protection even had time to work. This proves that the current problem is not a lack of caution on the part of investors, but the failure of traditional insurance mechanisms in a market that has been completely reconfigured by very short-term products.

This strategy blew up in mid-air this week.

Why? Because the modern market no longer follows the rules of the past: the VIX can be crushed in a single session, even in times of high tension, under the combined effect of dealers and the positive gamma generated by 0DTE options.

Let's try to explain the phenomenon...

The modern market no longer works as it used to. In the past, during periods of nervousness, uncertainty, or obvious risk, volatility rose. The VIX – the index supposed to measure market fear – reacted naturally: it rose as soon as investors began to doubt. It was logical, almost mechanical. Today, this mechanism is broken. The VIX can now collapse in a matter of minutes, even in the midst of tension, simply because the structure of the market has changed. It is no longer real risks that dictate volatility, but technical flows linked to ultra-short options.

To understand this phenomenon, two concepts need to be explained.

The first is the role of market makers – dealers – who continuously buy and sell options. When an investor buys an option, the dealer automatically takes the other side of the transaction and must then adjust their positions on the index to hedge.

The second is the rise of very short-term options, known as 0DTE, which expire on the same day and now account for a huge share of daily volumes.

When large quantities of ultra-short options are traded, dealers often find themselves in a “positive gamma” situation. In practical terms, this forces them to buy the index when it falls slightly and sell it when it rises a little, in order to balance their positions. This automatic mechanism acts as a stabilizing force: it dampens movements and crushes volatility. As soon as the market deviates, even slightly, dealers perform the opposite operation, which almost instantly brings prices back to their equilibrium point.

As a result, even when the market is clearly risky, indices are excessively expensive, or investors are nervous, the VIX no longer reacts. It is compressed like a spring. And when a large volume of 0DTE options expire on the same day, this positive gamma can cause a sharp drop in the VIX, because dealers no longer need to hedge as much and stop buying protection. In a matter of minutes, the volatility index falls, not because the risk has disappeared, but because the mechanics of options have temporarily neutralized it.

That is why, today, volatility no longer reflects market fear, but only the configuration of technical positions. The VIX can be battered in the midst of financial turmoil, simply because of the automatic flows generated by 0DTEs. To the uninformed observer, this gives the illusion that everything is fine. In reality, it mainly means that the natural warning mechanisms have been disabled.

The VIX was crushed on Tuesday, wiping out all gains

Tuesday was a textbook example.

The market wasn't really rising, the Nasdaq was stagnating, Bitcoin was stagnating... but the VIX plummeted by more than 12% in a matter of hours.

It's not that the risk has disappeared.

It's simply that dealers, in a long gamma position, mechanically crush volatility when options expire or deflate. A simple “breath” of gamma is then enough to melt away the entire price of protection in a matter of minutes.

The result: those who had paid for puts as insurance for weeks saw their premiums evaporate... without the market moving.

The VIX no longer has a memory. It reflects the moment, not the cumulative risk. And traditional insurance – the “firewalls” – no longer work.

Since April 1, insurance sellers have been crushed

Between April and today, all traditional hedging strategies have converged on the same impasse. Those who bought long-term puts were wiped out: implied volatility collapsed much faster than prices, reducing their protection to nothing. Those who opted for very short puts, such as 0DTE or 1DTE, were wiped out day after day: these options expire so quickly that, without an immediate and severe market movement, they automatically lose all their value. Those who paid for hedges on the Nasdaq saw these hedges collapse under the effect of market makers' gamma, which artificially stabilizes index fluctuations and prevents volatility from rising. Those who bought the VIX as insurance accumulated dry losses, as the VIX no longer reflects real risk but the daily mechanics of very short options.

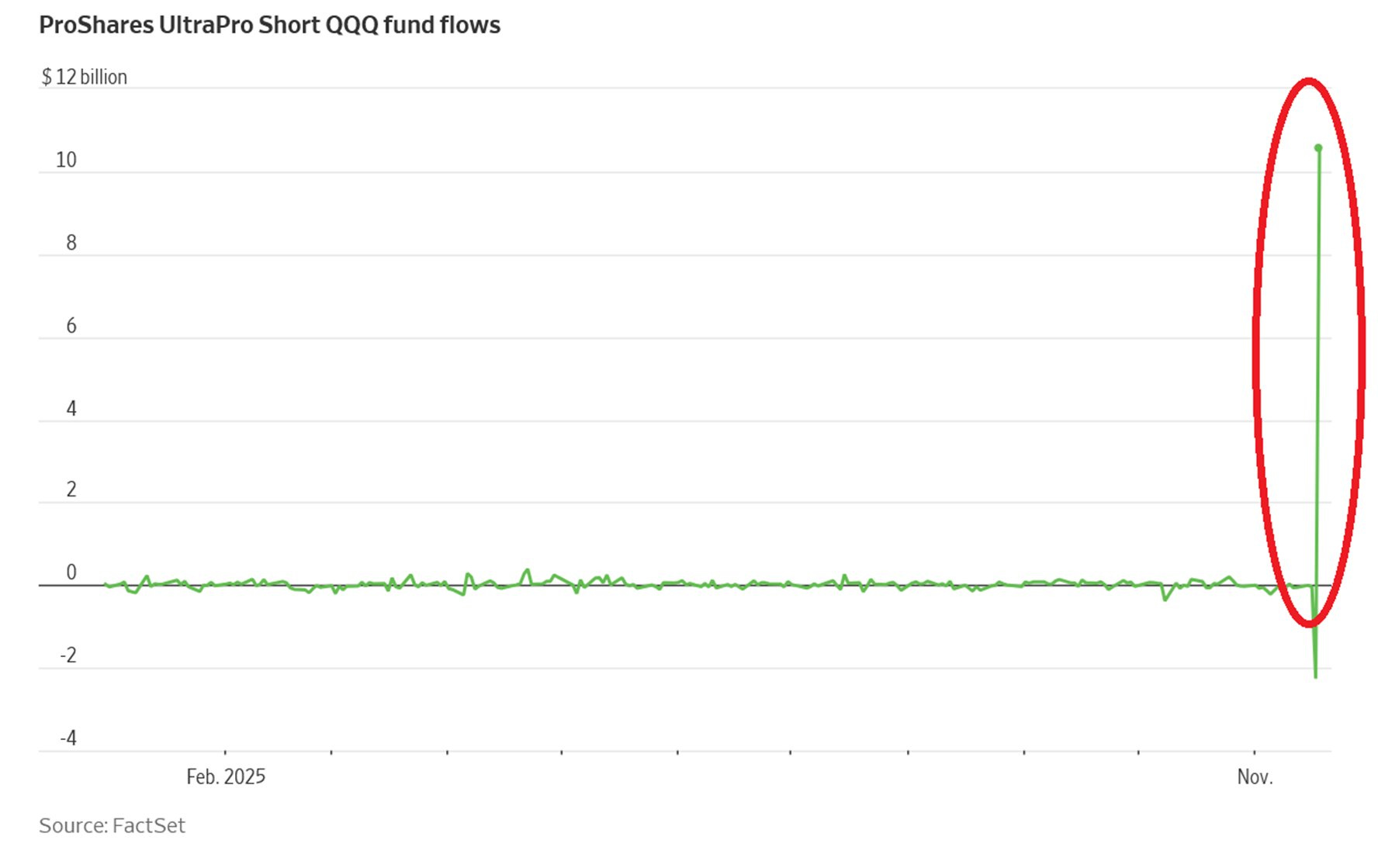

And those who turned to the SQQQ suffered what looks like a veritable bloodbath.

SQQQ is a publicly traded financial product, an inverse leveraged ETF. It is designed to rise when the Nasdaq falls, and even to rise three times faster than the index falls on a given day. On paper, this seems like an effective hedge: if the Nasdaq falls 1%, SQQQ should theoretically rise 3%. Many thought that with such an expensive market concentrated around a few tech giants, this type of tool would offer simple and quick protection. But what many investors don't know is that this product – like all leveraged ETFs – mechanically deteriorates over time. Every day, it resets its exposure: if the index stagnates or rises slightly, the SQQQ automatically loses value. This daily reset mechanism gradually erodes its price. If the index does not fall immediately, or if it fluctuates without direction, the leverage effect backfires on the investor.”

In the end, we arrive at a very simple phenomenon: people no longer take out insurance.

They no longer believe in it. They no longer see the point of it.

The market has conditioned them: all insurance is a sure loss.

And that is exactly what the market showed last Thursday, during the famous SQQQ purge.

Last Thursday: $12 billion wiped off SQQQ in a single trading session

This may be the most surreal scene of the year.

Traders who wanted to “hedge” bought $12 billion worth of SQQQ in a single day – a colossal amount, totally unusual.

The result? The next day, all these positions were wiped out.

Not because the Nasdaq soared, but because the VIX was crushed and gamma neutralized any attempt at a decline.

The Nasdaq barely moved. But the SQQQ lost. Again.

A tie. A flush out.

That's when we realized that even “short insurance” is worth very little in a market dominated by microstructure.

Conclusion: gold, the real insurance

If everyone has stopped paying for financial insurance (puts, VIX, SQQQ, Nasdaq shorts), it is not out of optimism. It is because the market has rendered such insurance unnecessary.

In a world where:

- 0DTEs crush volatility,

- dealers control every micro-tick,

- hedges evaporate before they even serve their purpose,

- and the Nasdaq never really corrects when it would make sense to do so.

There is only one asset left that does not depend on dealers, algorithms, or gamma, and that does not need volatility to do its job of providing protection: physical gold.

Gold cannot be crushed by leverage.

Gold cannot be neutralized by a market maker.

Gold cannot be vaporized by a 0DTE.

Gold does not disappear when the VIX “crashes.”

In a financial insurance system that has become inoperative, gold remains the only protection policy that does not destroy its own premium.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.