On July 29, 2025, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) conducted three separate monetary interventions in a single day, an exceptionally rare occurrence. Among other measures, it offered to lend Japanese government bonds (JGBs) on the spot market twice, once in the morning and once in the afternoon. In addition, it offered US dollars in exchange for pooled collateral – a mechanism whereby the Federal Reserve (Fed) provides dollars to an institution, such as a foreign central bank, in exchange for a basket of assets as collateral, in order to ensure rapid liquidity in times of stress. These measures are intended to support the smooth functioning of the Japanese bond market, which is showing increasing signs of gridlock.

JGB lending operations are generally triggered when certain securities become unavailable or expensive to borrow, a possible sign of a shortage in the repo market. This market plays a key role in providing banks, hedge funds, and other financial institutions with access to short-term liquidity. When the Bank of Japan is forced to intervene several times in a single day, this reflects a malfunction in traditional financing channels and suggests a weakening of confidence in the liquidity of Japanese government bonds.

As I had written last week, the agreement between the United States and Japan continues to have a marked effect on the Japanese debt market.

Trump's aggressive trade negotiations with Japan and Europe have a clear strategic objective: to bring Japanese and European investors back to the US debt market. With the US set to raise huge amounts of money on the markets in the coming months, the US Treasury will act as a veritable vacuum cleaner for liquidity. Trump wants to secure external support as quickly as possible to absorb this wave of issuance.

Last week's investment pledge by Japan is a perfect illustration of this: on closer inspection, these are not industrial or capital investments, but essentially loans to the US, with barely 4% allocated to equities. Similarly, the $600 billion that Europe plans to mobilize through future trade partnerships could also be entirely directed toward financing US debt.

The US Treasury has announced that it plans to borrow $1.7 trillion in net debt on the markets for the third quarter of 2025. This figure is up $453 billion from the April forecast. This dramatic revision is largely due to a carryover effect: in the second quarter, due to political gridlock over the debt ceiling, the Treasury was only able to issue $65 billion in debt, whereas it had initially planned to raise more than $500 billion. Most of these issuances have therefore been postponed to the current quarter.

But this postponement does not fully explain the scale of the increase. Even when the effect of the delay is neutralized, actual borrowing requirements rose by around $60 billion. This means that the federal government's cash flow is more negative than expected and that the budget deficit continues to widen beyond expectations. Added to this is the Treasury's goal of replenishing its cash balance, the famous Treasury General Account (TGA), which it wants to raise to $850 billion by the end of September.

In practice, this means that the markets will have to absorb a massive wave of Treasury bill issuance, particularly in the short term. This is Bessent's crazy gamble!

This colossal borrowing amount – more than $1 trillion in a single quarter – is historic outside of a period of major crisis. It also puts into perspective the huge gap between political rhetoric on revenue and the reality of the federal government's financing needs. Donald Trump recently highlighted the revenue generated by tariffs, particularly on Chinese products, as an important source of income for the United States. However, even assuming that these tariffs bring in $25 billion to $30 billion per quarter, this is still a drop in the bucket compared to the Treasury's current needs. The Treasury needs to raise 40 times more than the revenue from these tariffs to finance its deficit and replenish its cash reserves. This contrast highlights how exceptional or symbolic revenues are not enough to bridge the structural budget gap, and how difficult it is to contain the US debt trajectory without major tax or budgetary reform.

While this surge in financing needs is partly due to a mechanical carryover from the debt ceiling impasse, it also signals a deeper deterioration in the US budget situation. The Treasury is entering a phase where it must raise huge amounts of money in record time – an unprecedented situation that could have significant repercussions for financial stability and the bond market.

This situation is forcing the US authorities to channel global liquidity towards Treasury issues. But this role as a cash vacuum is starting to create serious tensions, particularly in Japan.

This pressure on Japanese government bonds comes at a time when the country is undergoing a major political crisis. Long-term JGB yields remain close to historic highs, against a backdrop of the ruling coalition losing its majority in the senate elections. Opposition parties, which advocate debt-financed tax cuts, have strengthened their position, increasing pressure on Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba, a proponent of fiscal austerity, to step down.

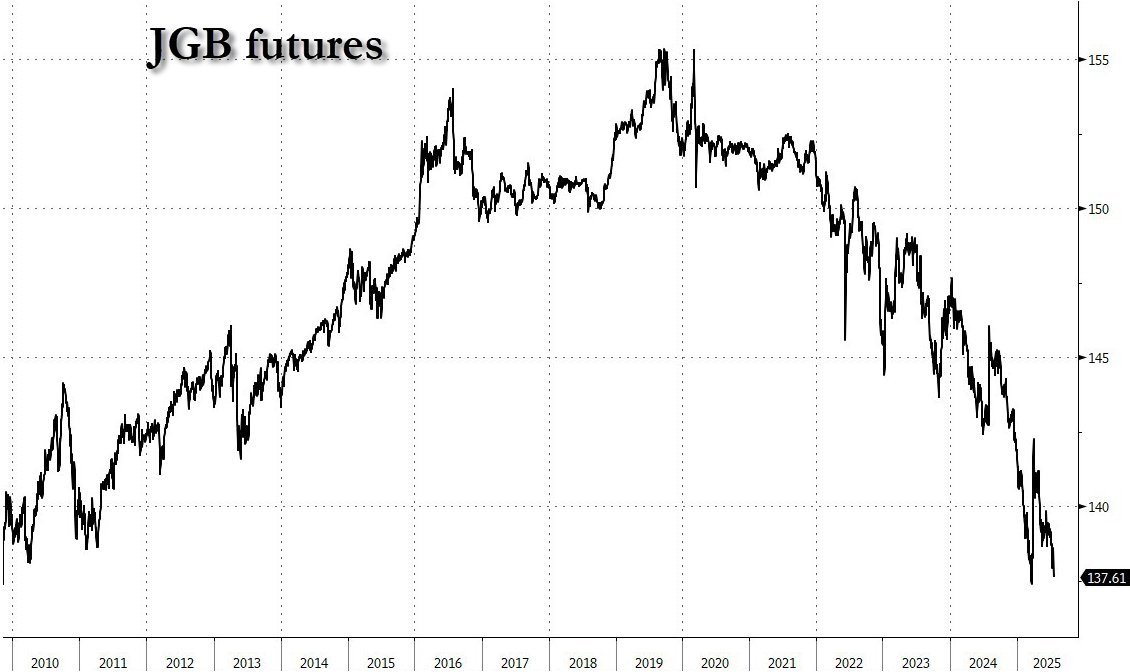

The central issue raised by the prolonged decline in Japanese government bond futures (JGB futures) is not just one of price, but above all one of liquidity. This is because price declines can be tolerated in a healthy market as long as securities remain easily tradable. What is now worrying investors is that JGBs appear to be losing their status as liquid assets, which is essential to their role in the global financial system.

Japanese bonds have historically been considered one of the safest and most liquid assets in Asia. They serve as collateral in many interbank transactions, as a benchmark in risk calculations, and as a pillar in the reserve management of large institutions. However, as the Bank of Japan has become the dominant – if not the sole – buyer in the market, the market's real depth has eroded. The less trading there is between private players, the less credible price formation there is, and the more liquidity deteriorates.

In other words, the JGB market gives the illusion of stability thanks to the BoJ's intervention, but this stability is based on an artificial equilibrium. As soon as conditions become tense – as during yen stress or a need for collateral – it becomes difficult to find a counterparty without causing violent price movements. An asset that cannot be sold quickly without significant loss can no longer be considered liquid.

And that is where the real danger lies: if JGBs are no longer perceived as reliable and liquid instruments, this calls into question the entire Japanese financial architecture and, beyond that, part of the global collateral chains. This could create systemic mistrust, accelerate capital outflows and force the BoJ to step up short-term interventions to preserve the appearance of liquidity. But these interventions, as we are now seeing several times a day, only expose the growing fragility of the market.

At the same time, the fact that the BoJ also has to provide US dollars against collateral shows that some players – most likely Japanese or Asian institutions – are short of dollars, a key currency in international financial transactions. This phenomenon is often a sign of global liquidity stress, as we have seen in previous crises.

If this type of intervention becomes the norm, it poses a sustainability problem. By intervening repeatedly to keep interest rates under control and ensure liquidity, the BoJ runs the risk of seeing the yen depreciate sharply, as the market perceives too great a distortion between the real price of debt and its artificially sustained value. In August 2024, a similar episode had already caused a mini-crash on the Japanese markets.

The operations carried out on July 29, 2025 signal worrying tensions in Japan's financial plumbing. If these interventions become daily or even multiple daily occurrences, it will mean that the bond market can no longer function without permanent assistance and that Japan is approaching a breaking point – either on interest rates or on its currency.

What is particularly worrying about the current situation is that despite three successive interventions by the Bank of Japan (BoJ) in a single day, 30-year interest rates on Japanese government bonds (JGBs) have started to rise again. This suggests that the market is beginning to challenge the BoJ's ability to control the yield curve, which has been a pillar of its monetary strategy until now.

Normally, intervention by the BoJ, either in the form of massive purchases of JGBs or collateralized lending facilities, would have been enough to stabilize rates and calm the market. But the fact that three intraday interventions were needed, and that long-term rates rose again despite this, indicates that confidence in the effectiveness of the BoJ's tools is eroding.

This phenomenon is doubly worrying. On the one hand, it signals that private investors are gradually deserting the secondary market for JGBs, leaving the BoJ alone at the helm, which greatly reduces the real liquidity of the market. On the other hand, it shows that demand for Japanese bonds is no longer sufficient to naturally contain rates, despite decades of ultra-low rates and unprecedented monetary support.

This return to higher long-term rates, against a backdrop of structural market fragility and repeated interventions, poses a systemic risk for Japan. An uncontrolled rise in rates could lead to massive losses on the balance sheets of Japanese financial institutions (banks, insurers, pension funds), which are heavily exposed to JGBs. Worse still, it would call into question the dogma of “yield curve control,” a pillar of Japanese monetary policy, and open the door to a crisis of confidence in the sustainability of Japan's public debt.

What is striking about the current situation is the apparent loss of effectiveness of the Bank of Japan's interventions. Last year, a similar support operation was enough to calm Japanese rates for several days, and this immediately had an impact on the price of gold in yen, which took a healthy break after a period of growth. The markets then regained a semblance of stability, albeit temporary.

Today, the situation is very different: even repeated interventions by the BoJ throughout the day are no longer able to calm the bond market for long. Rates rise again almost immediately, and, more importantly, gold denominated in yen is no longer taking any breathers. Instead of correcting or consolidating as in previous episodes, gold continues its parabolic rise, a clear sign of a flight to perceived quality... away from the yen.

This reflects a deeply worrying trend: the markets no longer believe in the Bank of Japan's ability to control the situation, and this is reflected in the immediate reaction of assets considered to be barometers of confidence — foremost among them gold in local currency. The latter is climbing not only because of the weak yen, but also because economic agents are beginning to doubt the credibility of the Japanese monetary framework itself.

In other words, we may be witnessing the beginning of a regime change, where the BoJ's interventions, once feared and effective, are now seen as insufficient, even as an admission of powerlessness.

And when even gold – which is supposed to fall when the central bank intervenes – continues to rise, it is a sign that the system is beginning to lose its traditional bearings.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.