Foreign investors continue to buy US debt on a massive scale.

In April 2025, despite high market volatility, net purchases of US corporate debt by non-residents approached $50 billion, according to the latest Treasury data:

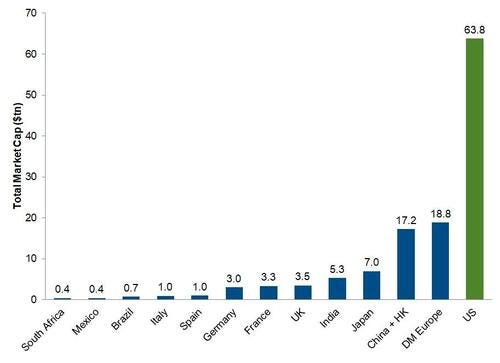

This appetite, far from waning, is part of a broader trend: US markets now account for over 70% of the developed world's market capitalization - an absolute record, illustrating the unprecedented Americanization of global portfolios:

With a market capitalization of $63.8 billion, the US stock market is now worth more than all the other markets listed below combined, which total $61.6 billion:

Markets are trading at historic levels. The S&P 500 has just broken a new record, having increased sixfold since the financial crisis:

Scott Bessent intends to capitalize on this flow. The U.S. Treasury Secretary is repeating the strategy initiated by Janet Yellen: issuing ever more very short-term debt to artificially contain refinancing costs. But he has amplified its scope, in a maneuver described by several observers as Activist Treasury Issuance.

The Treasury has thus increased the amounts allocated to weekly auctions of 4- and 8-week T-Bills, raising them to $80 billion and $70 billion respectively.

The aim is twofold: to capture the markets' appetite for liquid, well-remunerated assets, while sending investors a signal of stability and support in the very short term. The liquidity of T-Bills thus becomes a political tool, designed to reassure international flows.

But this strategy comes at a particularly critical time.

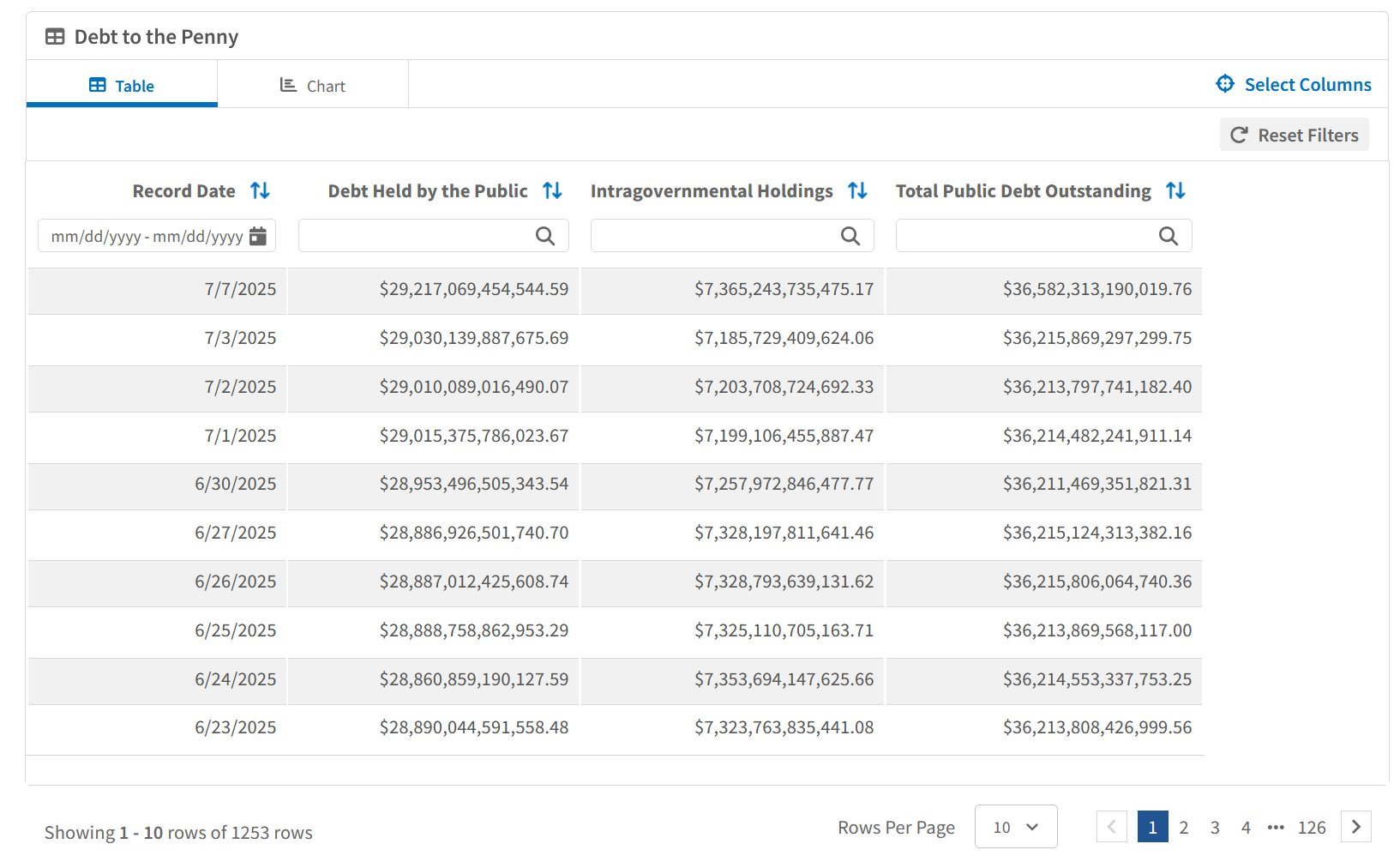

U.S. debt is exploding: on July 7, 2025, federal debt jumped by $366 billion in a single day, crossing the $36.58 trillion mark.

The acceleration is spectacular, as official Treasury data show. And the outlook is far from reassuring: markets are now anticipating, as a central scenario, public debt reaching $46 trillion by 2028 - twice what it was in 2020.

Bessent's gamble is likely to be complicated by the context of global bond markets. In the UK, long rates - particularly at 20 and 30 years - continue to rise, and are now above the levels reached at the peak of the Truss Plan budget crisis in 2022. And this without any recent political shock to justify such tension. This movement reflects a deeper, structural loss of market confidence in the sovereign debt of Western economies.

The UK epitomizes this growing vulnerability. Its massive exposure to debt, dependence on foreign capital and punitive fiscal policy - marked by tax hikes and the flight of wealthy taxpayers - are fuelling an increasingly unstable environment.

Technical projections point to long-term rates as high as 6.1%, or even 7.6%: levels that would make debt servicing difficult to sustain, even for a developed economy.

More broadly, this tension is part of a worldwide cycle of gradual disengagement from sovereign bonds, accentuated by the end of the zero interest rate era and the erosion of monetary policy credibility.

Asset managers are finally realizing that the great bond bull cycle is a thing of the past - a realization spectacularly illustrated by Dutch pension funds.

According to the Financial Times, these major players in the European pension system are preparing to sell around €125 billion of sovereign bonds, mainly with long maturities. This move, linked to a structural reform of the pension system in the Netherlands, is likely to put significant pressure on European public debt markets, already weakened by the economic slowdown, the end of ECB support and historically high debt levels.

The message is clear: government bonds are no longer perceived as risk-free assets, and their long-term growth potential is now in doubt. The “low rates forever” paradigm has come to an end, and institutional managers - who, for years, have been the last to adjust their portfolios - are beginning to reposition themselves in the face of a structurally higher interest-rate regime.

This realignment will not be without consequences: it could amplify spread volatility, weaken the finances of the most exposed countries and mark the real beginning of bond disintermediation in the eurozone.

In this context, accelerating the pace of auctions becomes a real challenge. The Treasury is no longer issuing to finance a current account deficit, but to meet a massive refinancing requirement, with the average duration of its debt plummeting. Every bid becomes a test, every tender a signal of confidence - or rupture.

The objective is clear: exploit the global appetite for T-bills, still perceived as risk-free assets despite the structural imbalances in US public finances. With short-term yields above 5%, and abundant liquidity in search of yield without duration, the market has so far absorbed these massive issues without shuddering.

But this strategy is not without danger. By concentrating a growing share of the debt stock on maturities of a few weeks, the Treasury is weakening the financing structure of the United States. The average duration of debt continues to diminish, mechanically increasing the frequency of rollovers. Over the next year, more than $8 trillion will have to be refinanced. Every marginal rise in short-term rates, every liquidity friction, has an instant impact on the cost of debt servicing - which is already approaching $1.1 trillion a year.

Added to this is the growing political uncertainty surrounding Jerome Powell's position at the head of the Fed. Although his resignation has not been confirmed, pressure from Donald Trump and his entourage is mounting, fuelling speculation about a possible change in monetary governance in the months ahead. A successor more aligned with the priorities of the Republican executive could then initiate a rapid and aggressive rate cut, with the aim of relieving the burden of debt refinancing and supporting the markets ahead of the election. Such a move, motivated as much by budgetary as electoral considerations, would deal a severe blow to the Fed's independence - and risk permanently weakening the dollar as the world's monetary benchmark.

What if the market becomes saturated? What if, despite the structural support of the money markets, an auction were to fail or the rates demanded were to rise too quickly? The Treasury would then be faced with a perilous dilemma: either extend duration at prohibitive cost, or ask the Fed to intervene - at the risk of quantitative easing targeted at T-bills.

This type of intervention has already been seen in Turkey, where the central bank had to massively repurchase short-term debt to prevent the primary market from collapsing. Such action crosses a red line for a central bank that is supposed to remain independent. If the Fed were in turn to intervene in very short maturities to artificially support Treasury emissions, this would be tantamount to pure monetization of the short-term deficit - to the detriment of the dollar's credibility and monetary stability mandate.

In short, Bessent's gamble is to treat debt as a liquidity problem rather than a solvency problem. It's based on the idea that, as long as investors keep buying T-bills, the system will hold. But this line of reasoning overlooks a fundamental reality: sovereign risk does not always manifest itself over the long term. It can emerge suddenly, at a moment when confidence falters - in an auction room, on an autumn morning, when the market decides to say “no”.

Under these conditions, the current correction in precious metals can only be limited.

The gold price remains solidly underpinned by massive, regular purchases by central banks, which see it as a strategic bulwark against global imbalances. Silver, for its part, has shown remarkable resilience, despite intense selling pressure from bullion banks. On July 8, they sold the equivalent of half the world's annual production on the futures markets - without succeeding in pushing prices below $36. A symbolic failure, revealing a profound change in market elasticity.

Silver's surprising resilience can no doubt be explained by the spectacular surge in copper prices triggered by the announcement of new tariffs. Some saw it as yet another bluff by the US President, but the futures markets reacted with force, propelling prices to unprecedented levels. This imbalance is increasing the pressure on short sellers, whose room for manoeuvre is shrinking.

Silver shorts are becoming increasingly untenable. Their level remains historically high, despite the market's remarkable absorption capacity. If the Fed were to make an abrupt pivot - a scenario now deemed inevitable after Jerome Powell's expected resignation - a downward shock to rates would add to this tension, paving the way for a possible short squeeze on silver. Traders still seeking to contain prices could find themselves trapped in a market combining falling real rates, structural physical deficits and a now politically polarized environment.

In such an environment, betting against silver is less strategy than recklessness.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.