The sudden rise in 10-year yields on Japanese government bonds – reaching 1.60%, their highest level since 2008 – comes amid heightened macro-financial tensions.

The yield on 20-year Japanese bonds is on track to reach its highest level since the beginning of the century. This movement, which has yet to attract much media attention, could nevertheless have major consequences for global bond markets as a whole.

If the long end of the Japanese curve – historically stable and largely controlled by the Bank of Japan – were to truly break out of its channel, it would signal a structural shift. Japan, which has long been an island of bond market stability and a source of cheap capital via the yen carry trade, would then become a source of volatility.

An uncontrolled rise in Japanese long-term rates would force international investors to reassess the level of risk in other sovereign markets, particularly those where central banks have also saturated their own primary debt markets.

The shock would not be confined to the JGB curve: it could lead to a general increase in risk premiums on Western debt, an exit from yen carry trades, and a sharp rise in the overall cost of capital.

In other words, the markets are not prepared for Japan to cease being the implicit guarantor of global monetary stability. What is at stake on the 20-year curve is perhaps the awakening of a long-dormant volcano.

This move coincides with the announcement of a new trade agreement between the United States and Japan, presented as a bilateral breakthrough on automotive tariffs. Officially, Washington has agreed to reduce tariffs from 25% to 15% on certain Japanese vehicle imports.

But the simultaneous reaction of the bond and stock markets suggests that this agreement goes far beyond what has been made public.

According to several industry sources, Japan has agreed, in exchange for this tariff reduction, to use part of its sovereign wealth funds – notably the GPIF (Government Pension Investment Fund, which manages more than $1.5 trillion) and Japan Post Bank – to finance strategic US projects. There is talk of a package of guarantees and potential investments worth more than $550 billion, spread over several years, which would include infrastructure purchases, industrial co-financing, and potentially targeted purchases of US federal debt.

The implicit objective would be twofold: to avoid a trade war that would damage the Japanese automotive industry, while helping to stabilize the US debt market amid chronic budget deficits in Washington. This discreet support would be a way for Japan to “pay” for the tariff cuts without resorting to direct budget transfers.

Japanese stock markets welcomed the agreement: the Nikkei index jumped 2.1% on the day following the announcement, with Toyota (+8%) and Honda (+3.9%) leading the gains. Investors anticipate an immediate competitive advantage for Japanese vehicles in the US market, especially since models that are “fully made in Japan” could now enter the market on more favorable terms than certain vehicles assembled in Canada or Mexico, even though they contain a high proportion of US components.

Meanwhile, Ford, GM, and Tesla are facing skyrocketing costs: +50% for steel and copper, +25% for vehicles produced in Canada or Mexico, and up to +55% for imports from China.

The result: while US manufacturers are facing widespread cost increases, Toyota benefits from a simple framework and a clear competitive advantage. This is ironic for a policy that is supposed to support the US automotive industry.

But this apparent relief on the equity markets contrasts sharply with the alarm bells ringing on the bond market. In a single trading session, the Japanese 10-year yield jumped by more than 5%, an exceptionally large move for a market as controlled as the JGB market. This shock reflects a double break: on the one hand, the sudden loss of visibility on Japan's fiscal trajectory, and on the other, internal political instability, with Ishiba's government now deprived of a majority in the Senate.

Even more worrying, this tension seems to reflect growing concern about the implicit use of public debt to finance the geopolitical counterparties of the agreement with the United States. In other words, investors fear that Japan has agreed – behind the scenes – to financially support US industrial policy, even if it means compromising its own financial stability. The market's message is clear: confidence is eroding, and a risk premium is now required to continue financing the Japanese government.

The lack of official communication on the exact terms of the agreement, combined with the Bank of Japan's shrinking room for maneuver – it already holds more than 53% of total outstanding JGBs – is heightening mistrust. The BoJ, which has been engaged in a process of gradually reducing its bond purchases (tapering) since July 2024, now finds itself powerless in the face of capital flight that could accelerate. And with good reason: if Japan does indeed commit, even implicitly, to financing US debt as part of a broader geopolitical agreement, what rational investor would still choose to buy Japanese debt?

At equivalent yields, US debt offers far greater liquidity, market depth and political stability. In other words, by accepting this role of discreet supporter of the US Treasury, Japan is undermining the attractiveness of its own bonds. The Bank of Japan, which can no longer launch massive quantitative easing (QE) without losing all credibility, finds itself in a dead end: the market is anticipating a sustained rise in rates, and private buyers are now demanding a significantly higher risk premium to hold JGBs.

Japan is currently mobilizing public funds to support US debt through institutional players such as the GPIF and Japan Post Bank. Although not officially confirmed, this strategic move appears to be an integral part of the new trade agreement with the US. By redirecting some of its capital towards Treasuries, Tokyo is seeking tariff relief for its automotive industry while consolidating the bilateral alliance. However, this choice automatically weakens the attractiveness of its own sovereign debt by reducing domestic demand for JGBs.

In this context, the market could anticipate a monetary response from the Bank of Japan. If investors fear a loss of control over government financing, they could bet on a return to QE. Such a prospect would imply the resumption of massive bond purchases by the BoJ, and therefore additional money creation, which would logically weigh on the yen.

And yet, a paradox could emerge. Despite this bearish monetary signal, the yen could strengthen in the short term. This is because rising financial tensions would prompt many investors to unwind their carry trade positions by buying back the yen they had borrowed to invest in risky assets. This disorderly but massive withdrawal of liquidity would artificially support the currency, in a context where Japanese economic fundamentals would not justify it.

This strengthening of the yen, should it occur, would therefore not reflect confidence or stability, but rather a technical reaction to a sharp contraction in capital flows.

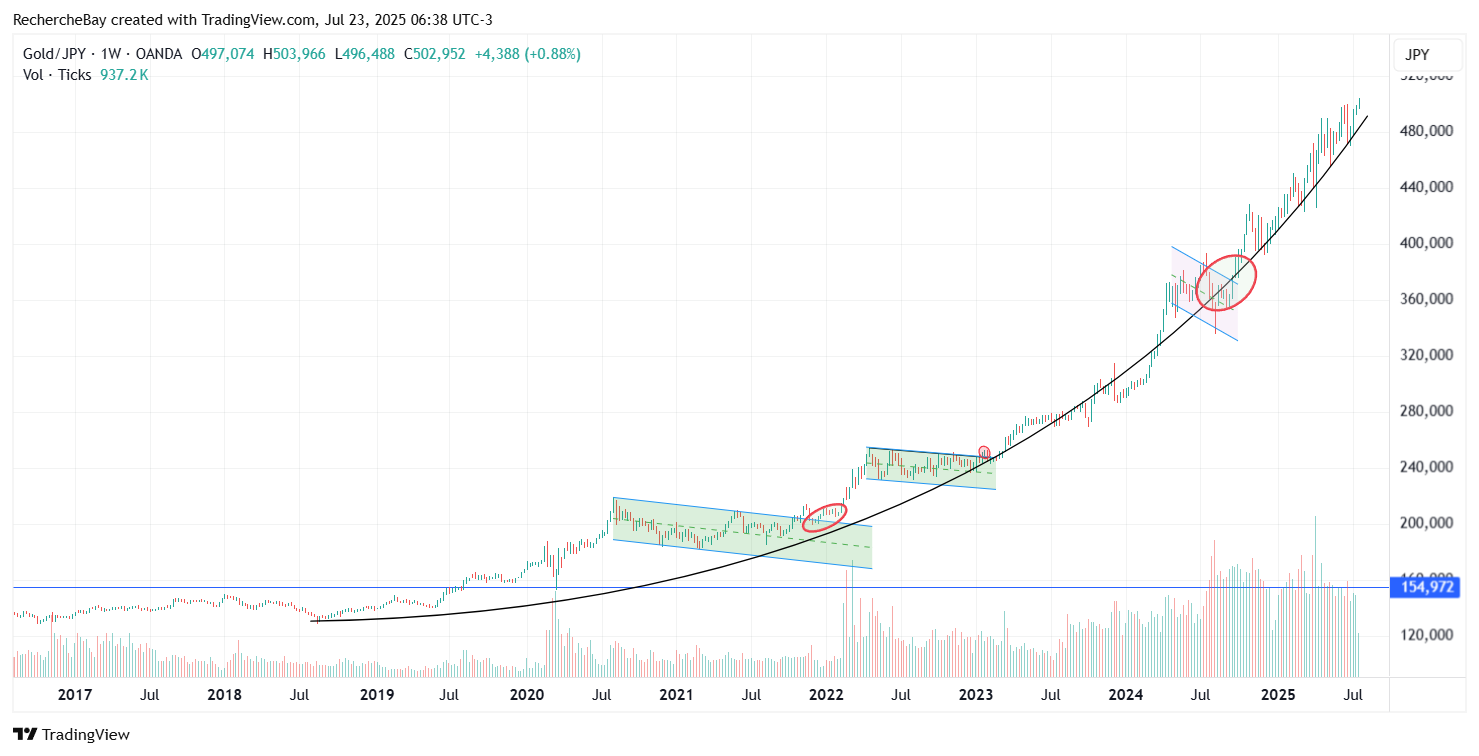

Gold denominated in yen reached another high this week, confirming a now parabolic upward trend.

This spectacular movement cannot be reduced to a simple mechanical appreciation of the yellow metal: it actually reflects growing investor mistrust of the Japanese currency and, more broadly, the strategic impasse in which the country finds itself.

For several months, the yen's depreciation against the dollar and other major currencies has automatically boosted the price of gold for Japanese savers. But beyond this exchange rate effect, the rise is part of a context of profound monetary instability. The Bank of Japan, locked into a policy of ultra-low interest rates and massive purchases of government bonds, is no longer able to stabilize either long-term interest rates or the currency. The partial refocusing of its bond purchases has only exacerbated tensions, revealing a loss of control over the yield curve – and with it, over inflation expectations.

In this context, physical gold is becoming the last credible refuge for Japanese households and institutions. It is no longer simply an anti-inflation asset, but an indicator of disruption: its dizzying rise in yen terms reflects a loss of confidence in the country's ability to maintain the value of its currency and the sustainability of its public debt. This is a powerful warning signal, especially as gold is reaching record highs in a historically deflationary country where the culture of cash and monetary stability remained firmly entrenched.

In other words, the bull market of gold in yen does not only say something about the yellow metal. It says much more about Japan itself.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.