I don't think it stands a snowball's chance in hell. Low inflation is over and we're not going back.

- We are moving into a multipolar reserve-currency world where the dollar will be challenged by the renminbi and the euro for reserve currency status.

- These currencies, especially the renminbi, would not necessarily be used as a reserve currency, but rather to settle trade. Gold could play an increased role here.

- The fact that China is running current account surpluses does not exclude their currency from becoming a global reserve currency. In fact, the US ran surpluses post-WW2, and this led the dollar on its global reserve currency path.

- The Chinese are using swap lines to settle international trade accounts. This is a fundamentally different approach from the dollar reserve framework and would mean that trade can occur in renminbi without nations needing to hold vast reserves of the currency.

- The various crises that today’s financial market participants have witnessed were easily solved by throwing money at whatever problem arose. The current inflation problem is different.

- This situation is also vastly different from the late 1970s, when Paul Volcker curbed inflation by prolonged high interest rates. Chronic underinvestment in the resource sector and labor issues will cause inflation to remain sticky.

- The traditional 60/40 portfolio allocation will struggle in this environment. Zoltan recommends a 20/40/20/20 (cash, stocks, bonds, and commodities).

Zoltan Pozsar is one of the most widely followed investment strategists in the world today. Zoltan was a senior adviser to the US Department of the Treasury, where he advised the Office of Debt Management and the Office of Financial Research, and served as the Treasury's liaison to the FSB on matters of financial innovation.

Ronnie Stöferle : Zoltan, thank you very much for taking the time. It’s a great pleasure. Here with me is my dear friend Niko Jilch, financial journalist and a very-well-known podcaster.

Niko Jilch : Hi, Zoltan, it’s very nice to meet you. I’ve been reading all your stuff lately.

Zoltan Pozsar : It’s very good to meet both of you. Thank you for the invitation.

Ronnie Stöferle : Niko has been responsible for the chapter about de-dollarization in our In Gold We Trust report for many years. This discussion will evolve around that topic. But there are many things to talk about these days.

Zoltan, as you are from Hungary, I want to ask you a personal question. After the Second World War, the Hungarian pengő suffered the highest rate of hyperinflation ever recorded in human history. The hyperinflation in Hungary was so out of control that at one stage that it took about 15 hours for prices to double and about four days for the pengő to lose 90% of its original value. Like Germans and Austrians, do you think that Hungarians, due to their hyperinflationary history, are especially concerned when it comes to inflation? Are they especially interested in the topic of gold? What’s your take on that?

Zoltan Pozsar : I heard about that pengő story quite a bit from my grandmother. But you know, since then we have the forint in Hungary, and I think a lot of these hyperinflationary episodes were just about being on the wrong side of the outcome of WW2. I don’t think that the general population or the policymaking circles in Hungary still think about or base policy decisions on the post-Second World War pengő experience. But you could have posed the same question to anyone in Germany, and you’d get the same answer. It’s a particular phase in history, and I think they’ve learned lessons from it.

Ronnie Stöferle : I’m referring to that because many people our age used to get little gold coins from our grandparents. It is in our monetary DNA, due to the experiences of our grandparents. If you look at gold purchases in Germany, for example, they are significantly higher than in most other countries. I think that has to do with our attitude when it comes to inflation. Compare this to the United States, where everybody is still scared of the deflationary Great Depression.

Zoltan Pozsar : That’s right. We are all afraid of different things, but in the general population in Hungary this is not nearly as strong a theme as in Germany. But the Hungarian central bank has been one of the central banks that’s been quite early in buying gold.

Niko Jilch : Yes. Let’s get going with a very actionable question. You just mentioned Hungary buying gold. I think the Hungarian central bank was one of the European central banks buying gold recently. Europe already has a lot of gold. Why are central banks stockpiling gold and do you think that is going to accelerate? What are you looking at in this regard?

Zoltan Pozsar : Yes, I think it’s going to accelerate. I think reserve management practices, the way central banks manage their foreign exchange reserves, is going to go through transformative change over the next five to ten years. There are a number of reasons for this. One reason is that geopolitics is a big theme again; we are living through a period of “great power” conflict.

We can mention these great powers: China, the US and Russia and their various proxies. But trust in the dollar – I have to be careful about how I phrase this – the dollar will still be used as a reserve currency in certain parts of the world, but there will be other parts where that’s no longer going to be the case. The dollar is not going away overnight, and it’s going to still be a reserve currency and used for invoicing and trade and all that in parts of the world.

But there will be other parts of the world that are not going to rely on the dollar as much. One example would be Russia. Russia’s forex reserves have been frozen. That means that their dollars and euros and yen assets became unavailable for use.

There’s legal risk, there’s sanctions risk, and there’s geopolitical risk. If you look at the world in terms of two camps – aligned and nonaligned, East and West, and so on – some regions, the global East, the global South, the nonaligned regions, and the ones that have foreign policy conflicts or disagreements with the United States, will, I think, be less likely to use the dollar as a reserve asset.

There’s a number of subplots to this. They will be looking for other reserve assets as an alternative. I think gold is going to feature very prominently there. As a matter of fact, since the outbreak of hostilities in Ukraine and the freezing of Russia’s forex reserves, foreign central banks’ purchases of gold have accelerated quite a bit.

We see this in the IMF data; we see this in the data published by the World Gold Council; you read about it every day in the financial press. The difference between gold and US dollars as a reserve asset is: The textbooks refer to the latter as “inside money” and gold as “outside money”. What that means is that when you hold gold and you physically hold it in your country, in the basement of your central bank, you basically control that monetary base. But when you hold reserves in the form of US dollars, you ultimately are going to hold those in either bank deposits in a bank that’s ultimately controlled by a state, or at a central bank controlled by a state, or in US government securities or other sovereign debt claims that are ultimately controlled by a state. Thus, you’re not really in control of that money; you’re basically always at the mercy of someone giving you access to it and basically reneging on that access and that promise.

That is one reason why the world is looking at alternatives. I would add two other things that are going to change reserve management practices. Foreign countries hold US dollars as FX reserves because at the end of the day you need to have some currency in reserve that you will be able to tap into as a country to import essential goods. When people think about why central banks hold FX reserves, there’s only a few reasons:

- You need to import oil and wheat and whatever you don’t produce at home, and the price of commodities is denominated in US dollars, and it’s invoiced in US dollars. There’s no way around it. Essentials that you import are priced in dollars.

- When the local banking system has dollar liabilities and there’s some crisis, you have to provide some backstop to that; or if your corporations borrow too much offshore in US dollars, and they run into problems, you will have to cover that.

- There is a new theme where, in addition to gold, foreign central banks are going to start accumulating currencies other than just the dollar because there will be more oil that’s going to be invoiced in renminbi and other currencies. It’s no longer the case that countries can rely only on dollars to import essentials that they need.

Niko Jilch : You wrote about the birth of the petro-yuan, and Europe regularly tries to do energy deals using the euro. In a multipolar world, will there be one single reserve currency, or do we have to get rid of that thought? Europe has aligned itself with the US and they have sanctioned Russian currency reserves. Thus, China and Russia have turned hostile against the euro. Do you consider the euro basically just the “dollar-lite” at this point, or is it an alternative? Reserve currency-wise, it is still number two.

Zoltan Pozsar : I think there will be three dominant currencies: the dollar, the renminbi, and then the euro is going to be like a third wheel. The euro was a very important creation in many respects. One reason why it was so important is that it gave Europe the ability to pay for its commodity imports with its own currency. It gave Europe commodity import bill sovereignty, if you will. They didn’t have to hustle to earn dollars to be able to import the oil and gas that they need, because the OPEC countries and Russia took euros from them.

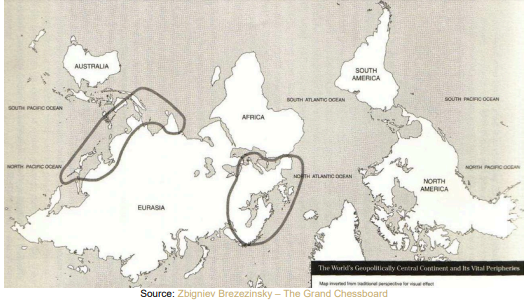

There’s obviously going to be a change in a world where you will be more dependent on energy imports from North America. The US will demand dollars for their energy exports. The other thing about the euro is that China is reducing the dollar’s weight in its basket, but it’s increasing the euro’s weight. It’s kind of a hard question to answer because Europe is a great prize in this “great game” of the 21st century, which China is going to be playing on the Eurasian landmass and in Africa and the Middle East. Where the gravitational pull of things will fall, Europe going forward is a big question in terms of the euro’s status as a reserve currency and whether their share is going to go up or down.

Europe is at the geographical end of the Belt and Road Initiative, so there’s that pull on the one side and then there’s the trans-Atlantic pull. We will have to see how that transpires, but I think it’s helpful to frame your thinking about the next five to ten years in macro, money, interest rate markets and global economics as follows: There is Belt and Road and Eurasia; it’s all of Asia, all of Europe and the Middle East, Russia, North Africa and Africa in general. The world island, so to speak.

Then there is what we refer to as the G7. North America, Australia, Japan and other little islands and a peninsula here and there. These are basically the two “economic blocs”. If you think about the macro discourse, we are talking about the aligned countries and nonaligned countries. Everything that you see in terms of supply chains and globalization is going to also happen in the world of money, because supply chains are payment chains in reverse.

If you realign supply chains along the lines of political allegiance – who is your friend and who is not – you will also realign the currency in which you will invoice some of these supply chains and trade relations. Eurasia is looking like a renminbi slash gold block. Then what we refer to as the G7 looks like a dollar block.

I think Europe is a question mark in there. It’s going be fought over.

Ronnie Stöferle : We’ve observed French president Macron going to China recently, causing some turbulence, especially in the US, when he said some things that Americans didn’t appreciate. Isn’t it important to differentiate between a reserve currency and a trade currency? I think for the renminbi to become a trade currency for trading oil and gas is pretty easy. But to become a reserve currency, wouldn’t they have to open up their capital accounts, deepen their capital markets, and let the renminbi start to float?

Zoltan Pozsar : I get that question a lot. What I usually answer to that is: Babies are not born walking and talking and trading interest rates; it’s a 20-year journey. They are born and then they stumble around; then they formulate sentences; then they make their case and decide what they want to do in life, and then they do it in life. Then they have a midlife crisis.

The dollar has gone through all of that. After the Second World War, when we read the history books, it became the reserve currency, but it was still a journey to get there. Post-war reconstruction of Europe and Japan and the Marshall Plan. The US was running current account surpluses, much like China is running current account surpluses today. The US was providing financing to Germany, the UK and Japan to import all the stuff from American companies that they needed to build out their industries.

I am amazed when people say that China and the renminbi are becoming something big, but they have a current account surplus, so they cannot become a reserve currency. The US became a reserve currency with a current account surplus. It’s just that things later changed and then they turned to running a deficit.

The young generation of traders and market participants conceptually understand the dollar as a reserve currency, but are unaware that that status was born out of a surplus position.

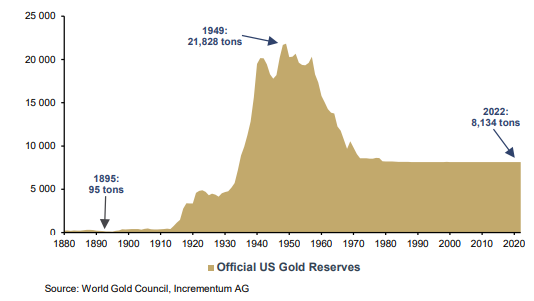

Ronnie Stöferle : The US also had more than 20,000 tons of gold, which was pretty important in establishing that trust in the dollar.

Zoltan Pozsar : Yes, exactly. All the gold flows went there, and that is where it started from. The fact that China is running current account surpluses is fine. There’s also a mechanism through which China is going to provide the world the renminbi that the world doesn’t have but will need in order to import stuff from China, and that’s swap lines. It’s not going to be like a Marshall Plan, but there are mechanisms through which China is going to pump money into the system.

The second thing is that China reopened the gold window in Shanghai with the Shanghai Gold Exchange. There’s that convertibility of offshore renminbi into gold if someone so wishes; that’s another important feature. Renminbi invoicing of oil has been happening for a number of years now, with all the usual suspects – Russia, Iran, Venezuela – but now it’s going to happen with the Saudis and the GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] countries at large. We are starting to see copper deals that are priced in renminbi with Brazil. When you read the statements and listen to the BRICS heads of state, they have an agenda. They are all busy de-dollarizing their cross-border trade flows; they are accepting renminbi as a means of payment; they are launching central bank digital currencies, which just basically means that they will bypass the Western banking system, for reasons we’ll discuss.

The money you have in the Western banking system is only yours if the political process that those banks ultimately report to or exist in allows you access to this money. When that trust is broken, you start building out your alternative payment and clearing systems.

China and the BRICS countries are basically doing with the renminbi all these steps that don’t seem to add up to much when you read about them in isolation; but when you look at them in the totality of things, and when you take a 10-year perspective about what they have been building, it adds up to quite something.

The other thing I would say is there’s capital flight from China. People want to keep their money anywhere but in China. Although certain countries have no option but to keep their money in China, other people want to keep their money elsewhere. I think it’s important to point out that China is not blocking those capital outflows with capital controls.

Outflows of capital from China mean that FX reserves are getting drained, which I don’t think China minds per se, because they are draining themselves from “geopolitically hot” assets. If capital flees because some domestic rich person thinks their money is safer in a condominium in New York, and they want to drain FX reserves to buy something, fine... that’s his problem, not the state’s problem anymore.

Depending on how you look at these things and the perspective you want to take, things are moving in a direction where a large part of the world is going to use the renminbi to a much larger extent. That’s a path toward becoming a major trade and reserve currency.

The other thing I would say about the reserve currency question is this: people have stashes of dollars because you need them in a crisis. That kind of thinking and that body language if you’re a central bank, came of age in an era where you didn’t have the dollar swap lines. And because you knew that if you’re short dollars, the next thing you’re going to have to do is go to the IMF and that’s going to be very tough and painful. China has a swap line with everybody. As a result, nobody will have to hoard renminbi to be able to trade with China. Had these swap lines existed in the 1980s, Southeast Asia would have had a different financial crisis than in 1997 – it was a liquidity crisis. These days, we deal with liquidity crises through swap lines.

I mention this because I don’t think that the journey for the renminbi to a reserve currency is that countries will start accumulating it; it’s going to be managed through swap lines. I keep on re-reading President Xi’s address to the GCC leaders; there’s a lot to unpack there. He says, “We are going to trade with each other a lot more and we are going to invoice everything in renminbi” and “You will have a surplus, I will have a deficit; or I will have a surplus and you will have a deficit, and then there’s going to be an interstate means of how we are going to recycle and manage the surpluses and deficits”.

It seems to me that what the Eastern vision for the Eurasian landmass under Belt and Road looks like from a monetary perspective is that there will be interstate mechanisms to recycle surpluses and deficits. And it’s not going to be as driven by the private sector as the dollar system is being driven by it; it’s going to be a more managed system. That’s how I think about China and renminbi as a reserve currency, more of a trading and invoicing service, or something like that.

Niko Jilch : I have two quick questions. The first is political. You have described how we’ve seen the first steps toward de-dollarization over the years; and now since Russia invaded Ukraine, everything has sped up tremendously. It’s now out in the open – the Saudis are talking about it. Has Russia basically reset the global financial system with this invasion?

Zoltan Pozsar : I’ll just observe that I think the news flow about de-dollarization and central bank digital currencies has taken on new momentum. If the freezing of Russia’s FX reserves was triggered by the war in the Ukraine, then yes, I think the world has changed. Things that were not accessible or thinkable before that invasion became real. It’s a change in the rules of the game. Things are changing fast, and countries are adapting.

Niko Jilch : You are in the US right now. What has the reaction from Washington been like? There was one statement from Yellen a couple of days ago where she talked about the danger that the dollar could lose reserve currency status because of sanctions. But that’s pretty much it. Everybody else is talking about this, but the US is not saying anything.

Zoltan Pozsar : Secretary Lew was one of the first, I think in 2015, to say you can weaponize the dollar and you can use it as a tool of war. But keep in mind that the more frequently you do that, the higher the risk that the rest of the world is going to adapt to that pattern. Christine Lagarde gave a fascinating speech last week with the same message. A year ago, Secretary Yellen dismissed my Bretton Woods III idea, but the tone of Yellen’s speech more recently was very different this time around. Things are changing. What’s been done has been done; trust is easy to lose and impossible to regain. The self-defense mechanism is there. Especially if you read the Financial Times every day, you get a sense that the BRICS countries have their own narrative and the G7 has its own narrative.

Which are the countries that are developing their CBDCs? That are de-dollarizing, that are accumulating gold, which are joining Project mBridge. When you are not aligned with the U.S. from a foreign policy or geopolitical perspective, you are being forced to take defensive measures to carve out a sphere where you have monetary sovereignty and you’re in control of things. The analogy I often bring up is, just as you don’t have Huawei cell towers in the United States, for obvious reasons, China doesn’t want to internationalize the renminbi through networks they don’t control, which are Western banks.

Ronnie Stöferle : Your most recent pieces were called “War and Interest Rates”, “War and Industrial Policy”, “War and Commodity Incumbrance”, “War and Currency Statecraft”, and “War and Peace”. I very much enjoyed reading them. I just picked up a report by Marko Papic from the Clocktower Group. The piece is called “War is Good”, which sounds quite counterintuitive; but he makes the point that investors should avoid extrapolating geopolitical disequilibrium into global conflict. He said that as we have previously seen in history, this multipolarity has for decades, even centuries, also led to an enormous amount of technological innovation. He also sees multipolarity injecting a burst of CAPEX that will probably lead to higher inflation in the short term, but for the longer term this should be disinflationary. Would you agree that we should not be too scared of global conflict or war, as it could also have positive effects like innovation, higher productivity, and so forth?

Zoltan Pozsar : Certain types of war can be good. We are in an age of unrestricted warfare, not just land, air and sea shooting at each other. If war is about technology, money, the control of commodities. etc., then there is no blood. But it’s war, nonetheless. It comes down to rare earths and oil and gas – commodity resources and genuine physical stuff. You don’t really want to think about history as being completely obsolete.

We need to be careful here, because we don’t want to reimagine history here, going forward. With the Napoleonic Wars and the Crimean Wars and First and Second World War, physical resources, land and industries, that’s the stuff you fought over. It’s hard to imagine that all conflict in the future will be about bits and bytes and data and spreadsheets and balance sheets. There is risk here. I think war is not good, because it’s a very risky game. Now, it usually happens in the domain of trade and technology and money, and then it spills over into uglier forms.

The catalyst for everything that we are talking about is a very tragic hot war with a very tragic civilian aspect, in Ukraine. I don’t think that war is good. Yes, it is going to be a catalyst for change, and this is going to mean a lot more investments. As I articulated in my thesis, we are going to pour a lot of money into rearming, reshoring, friendshoring, and energy transition. But again, all these themes are going to be very commodity-intensive and very labor-intensive. It’s going to be “my commodity” and “my industry” and “my labor” versus yours.

It’s not just a US versus China thing, it’s a US versus Europe thing as well, so it’s going to be very political. None of these things are going to be interest-rate-sensitive. The Fed can raise interest rates to 10%; we are still going to rearm; we are still going to friendshore; we are still going to pursue energy transition; because these are all national security considerations, and national security doesn’t care about the price of money, i.e. interest rates. Maybe 5-10 years down the road we are more self-sufficient and such, but I think the next five years are going to be complicated from an exchange-rate, inflation, and interest-rate perspective. My “War” dispatches were not “happy” pieces.

Ronnie Stöferle : I think the title was meant to be provocative on purpose. Marko Papic is from Yugoslavia, so he knows what war is about. He was referring to the competition and innovation that could happen when there’s new forces coming up. I wanted to ask you, regarding the topic of inflation, up until last year, central bankers all over the globe were telling us, it’s transitory, there’s no stagflation, and “It looks like a hump” (Christine Lagarde).

Then, the Federal Reserve, especially, reacted very, very aggressively. Now we are seeing something that Gavekal calls “pessimistic bulls”, investors hoping that inflation rates will come down, that this will influence the Federal Reserve; and this will lead to us going back to the old regime where, when the Fed surprises, they only surprise in one direction and that direction is up. One of our takes is that we will see much more inflation volatility. The “Great Moderation” is over; forget about that. We see upcoming inflation volatility in inflationary waves.

Would you say that the first inflationary wave is over and that we should expect more inflationary waves? There’s now this very close co-operation between monetary and fiscal policy. We’re seeing problems in demographics, in the labor market, deglobalization, things like that. Would you say that we will go back to the times when 2% was the upper limit for inflation?

Zoltan Pozsar : Two percent inflation and going back to the old world, I don’t think it stands a snowball’s chance in hell. Low inflation is over and we’re not going back. There are a number of reasons for that:

- Inflation has been a topic for three years now. We started to fight it a year ago, but it’s been a part of our lives for much longer. The CPI is up, I think, 20% since the pandemic and wages are up about 10%. There’s still a deficit in terms of what your money buys versus this statistical artifact that’s the CPI. Everybody has their own basket. There’s a saying: “Inflation expectations are well anchored when nobody talks about inflation”. Now, it’s increasingly hard to talk to any investors without talking about inflation. So, inflation expectations are not well anchored anymore.

- Wall Street and investors are very young. This is an industry unlike physics, where we all stand on the shoulders of earlier giants – physics is a science where knowledge is cumulative. Finance is cyclical; you make your money in the industry and then you retire and grill tomatoes. Then everybody else has to relearn everything you knew and again retire that knowledge as they go along. If you’re young, let’s say 35-45 years old, you haven’t really seen anything but lower interest rates andlow inflation. In terms of how you think about inflation, it’s a new skill you have to acquire, because it’s not a variable you had to think about in the past.

What that means in practical terms is that there’s this tendency to think about inflation as if it was another basis on a Bloomberg screen that blew out, and it’s going to mean-revert. What do I mean by that? At your age and my age, our formative experiences in financial markets are the Asian Financial Crisis, 2008, some spread blowouts since 2015, the Covid pandemic; all of these things were crises of bases where FX spreads were broken, and then AAA CDOs and AAA Treasuries turned out to not be the same thing. There was a basis between those two, and the cash/Treasury futures basis broke down in March of 2020, when the pandemic hit and we didn’t really have a risk-free curve for a couple of days until the Fed stepped in.

These are all easy things, because all you need to do to fix these dislocations is, you throw balance sheet at the problem, which in English means someone has to provide an emergency loan or you have to do QE and pump money in the system; and then, once the money is there, the basis dislocations disappear.

Just as the UK had this mini budget problem, we have the problem with SVB. All we had to do is say, “Here, we give you money, we guarantee deposits, problem solved”. So, these are easy problems. With inflation there is a clear difference. And I think we are in love with this idea that Paul Volcker is a national hero because he raised rates to 20% and “that’s all it takes to get inflation down”. Well, not really. Paul Volcker is a legendary policymaker, but he was lucky. There are two reasons I will mention.

- The OPEC price shocks that precipitated the inflation problems happened in the early 1970s. When prices go up, people start drilling more; and supply increased in that decade after the OPEC price shocks. This was the period when the North Sea oil fields were developed, and Norway started to pump in the North Sea and Canada drilled more and Texas drilled more and we were just swimming in oil. Then Paul Volcker arrived in the early 1980s, raised interest rates and caused a deep recession, and the demand for oil and oil prices collapsed. So that’s fantastic. More oil, less demand. That’s how you get inflation down.

- The second thing was the labor force back in Volcker’s time. There were more people working because of the boomer generation, and female labor force participation was going up, so there was a lot of labor coming in. Also, the politics around wages was changing, because in 1981 President Reagan famously fired air traffic controllers because they dared to go on strike. So, it’s easy to get inflation down when energy and labor are going down for fundamental reasons. There’s more supply, and politics is supportive.

Today, oil prices are elevated and we haven’t invested in oil and gas for a decade. Geopolitics is just getting worse. For Volcker it had got worse the decade before, and he was dealing with a very stable geopolitical environment by the time he was fighting inflation.

Now, the oil market and all other commodities are tight and geopolitics is getting nastier – look at the OPEC production cuts. OPEC+ wants to target USD 100 per barrel; we are below that. Probably they are going to cut more to get up to where they want to be in terms of target. The SPR has never been lower in history.

Labor? Very different from Volcker’s backdrop. The baby boomers are retiring, and millennials just don’t hustle as much as boomers did. The older millennials, the young generation today, all go to college; but they don’t have to work on the margin to put themselves through college, because student loan are flowing from the faucet, and their parents are richer, so the parents are going to put them through school. When you look at the boomer generation, their parents weren’t wealthy and their student loans were not as easy to come by, so they had to do odd jobs at restaurants and God knows where in order to make some money on the margin, to put themselves through college.

That was part of labor supply for lower-end restaurant and hospitality jobs. Those things are missing today. We have a stagnant labor force participation rate that’s actually falling on the margin; and we have a severe labor shortage, which only immigration can fix. But that’s not an easy solution and it’s also quite political. We have a skills gap where most of the jobs don’t require a college degree, but everybody that’s entering the labor force is overeducated for some of these jobs. That keeps the labor market from clearing.

The US labor market used to be something we were proud of, what made us different from Europe. In Europe, you can’t move around, because of the language barriers. If you speak German, you can’t have a job in France. That was not a problem in the US; you could just put your house up for sale and go to a different state. But, when mortgage rates are through the roof and housing is expensive, especially in the hot areas where you could get a job, you’re just not going to move around as much. So now there’s a labor mobility problem. This is a very different backdrop. I would say that people tend to overthink inflation and get technical about core inflation and this and that.

There are two things to keep in mind. The labor market is ridiculously tight. I don’t think unemployment is going to go up much during this hiking cycle. Because, if you’re an employer and you’re lucky enough to have the staff you need, you’re not going to get rid of them, because you will have a hard time hiring them back. If unemployment doesn’t really go up, the wage dynamics are going to remain robust in a very tight labor market; and that matters for services inflation, which is determined by the price of labor.

Then, on the other side, what you need to look at are the prices of food and energy, both of which are stochastic, and they are caught up in geopolitics. So, if you want to take a guess: Food and energy prices, do they have more upside or downside?

Probably more upside, because things are tight, things are geopolitical, mine versus yours. And that’s necessities – if the price of necessities is going up, and the labor market is tight, there’s going to be a lot of feedthrough from higher headline inflation to higher wage inflation; and core goods, whatever that is, doesn’t really matter as much. This is the price of flatscreen TVs and the price of used vehicles. Frankly, if you’re the Federal Reserve, you’re not going to care about used vehicle prices and the price of flatscreen TVs and D-RAM chips and all that stuff, because it’s not the type of thing that is going to determine what people are asking for in terms of wages.

I like to say that people go on strike not because the price of flatscreen TVs goes up, but because the prices of food, fuel and shelter go up and you can’t make a living.

So, I think that’s the near-term environment, and I think what we are seeing is that interest rates have gone from zero to five percent. We have had little local fires, which the Bank of England and the Fed were very eager to put out as soon as they surfaced. Crises that were dealt with very quickly. But we don’t really have much progress to show for all these interest rate hikes. Housing is slowing and demand for cars is slowing, but unemployment is still very low. When you look at the earnings of consumer staple companies like Nestlé or Coca Cola, or Procter and Gamble, you don’t really see the economy falling off a cliff. People are eating price increases, and it’s not like they are spending less. It’s going to be a persistent problem, and it’s just wishful thinking when the market thinks that we are going to be cutting interest rates by the end of the year.

Everybody who has assets and anybody who grew up as a financial market professional, don’t forget that we’ve done QE for more than 10 years. That’s like a lifetime in finance. But that’s not the only thing that can happen. Yeah, things are painful, but this is in terms of getting inflation down to targets. Unemployment is still three and a half percent, so I don’t really see the pain in the economy. More will be necessary.

I think it’s important to think about inflation in cyclical terms near-term, as in what happens to it because of the hiking cycle. What I just told you there is, inflation is probably going to be stickier than you think. Definitely for the next one or two years. Tight labor markets, high wage inflation, core inflation, all well above target, around four or five percent.

The second thing is these industrial policy things that we talked about. Rearming and reshoring and energy transition; this is going to be like an investment renaissance that’s coming. We can already read about the Inflation Reduction Act with billions in investment so far in its first year, and there’s a lot of stuff coming. Recessions are usually not associated with an investment boom. The longer inflation persists, and if the Federal Reserve doesn’t manage to drive us into a recession where unemployment goes up meaningfully, I think we’re going to run out of time, because all these investment themes are gathering momentum. And once they gather momentum, as I said, it’s going to require a lot of labor and a lot of commodities. That’s just going to add to the inflation problem and it’s going to make the Fed’s job more complicated.

Niko Jilch : This brings up a core question that everybody wants to know the answer to. How do you invest for this environment; what assets do you expect to do well?

Zoltan Pozsar : I think this means all sorts of bad things for a 60/40 portfolio, the standard portfolio construction. At the very least, you need to do something like 20/20/20/40. Meaning 20% cash, 20% commodities, 20% bonds and 40% stocks.

Cash and commodities make sense to me for the following reasons. Cash used to be like a dirty asset, because it didn’t yield anything. But cash now yields a substantial amount. We shouldn’t be punting on the back end of the curve at about the 10-year yield, because if the market is wrong about recession and rate cuts and inflation, the US 10-year Treasury yield is going higher, not lower from here. When the yield curve is inverted, cash is actually a very nice asset; it gives you a very decent yield, the highest yield along the curve; and it gives you option value, which means that if you find some great assets to buy, you can. Commodities, I think, are equally important because, as I said, we are underinvested. Commodities are fundamentally tight; geopolitics is messing up commodities and resource nationalism is on the rise. Even if the supply is there, it’s going to come with special terms attached, and that’s going to mean higher prices, not lower.

Within that commodities basket, I think gold is going to have a very special meaning, simply because gold is coming back on the margin as a reserve asset and as a settlement medium for interstate capital flows. I think cash and commodities is a very good mix. I think you can also put, very prominently, some commodity-based equities into that portfolio and also some defensive stocks. Both of these will be value stocks, which are going to benefit from this environment. This is because growth stocks have owned the last decade and value stocks are going to own this decade. I think that’s a pretty healthy mix, but I would be very careful about broad equity exposure and I would be very careful of growth stocks.

Ronnie Stöferle : You worked for the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the most powerful branch of the Federal Reserve, and you meet a lot of institutional clients. I want to ask you, these topics we’re talking about, I know where you’re coming from, because I worked for a big bank in Austria but started discovering gold and the Austrian School of Economics. And at some point, I said: “I feel like a vegetarian in a big butchery”. Being in such an institution as the Federal Reserve, it’s not always easy to have alternative views.

I know the Federal Reserve is often being criticized for their timing, for being behind the curve. Do you think that within the Fed and also large institutional houses, these things we’re talking about: de-dollarization, inflation being very sticky for years to come, more fiscal expansion – you were talking about lithium, for another example – are those topics being discussed, or are they still just topics for outsiders and mavericks like us?

Zoltan Pozsar : Last year I had close to 400 client meetings, and these are hedge funds, banks, asset managers – everybody wants to talk about these things. Everybody wants to understand the implications. Some people are more advanced in terms of thinking about them, and for some it’s new. I have regular interactions with the Federal Reserve, they also receive my writings. I publish these ideas and pieces for institutional clients, central banks, and all that. Christine Lagarde is talking about them, and Janet Yellen is, too. Maybe a year ago, I felt like I was putting my neck a little too far out and it was risky because maybe my gut was horribly wrong and I shouldn’t say the things I said about Bretton Woods III. But the thesis is proving more and more correct by the day.

I now ride on the coattails of Christine Lagarde, who delivered a speech very much in the vein of my War dispatches. She talked about what it means for interest rates, for industrial policy, for currency dominance, and all that stuff. If you are a central bank, you don’t exist in a vacuum; you have to think about these things. The Fed is doing QT, but they don’t really determine how much duration they put back into the market. That’s totally up to the US Treasury. So, there’s co-operation there. Look at the body language around SVB. That was a crisis that couldn’t happen, because the Federal Reserve put out the fire so fast. The last thing you need when your status as a reserve currency is not what it used to be in certain parts of the world is a banking crisis (or a debt default because of the debt ceiling).

These topics are becoming more mainstream. When I talk to the most sophisticated macro hedge funds and investors, the common refrain that comes back is they’ve never seen an environment as complicated as this. There is consensus around gold; it’s a safe bet, and everything else is very uncertain. This is a very unique environment. I think we need to take a very, very broad perspective to actively reimagine and rethink our understanding of the world, because things are changing fast. The dollar and the renminbi and gold and money and commodities. I think they are all going to get caught up.

Niko Jilch : Did you just say that there’s consensus among sophisticated asset managers about gold?

Zoltan Pozsar : No, macro investors.

The full transcript, where we discuss more topics, including Zoltan’s views on recency bias, Niko and Ronnie making the case for Bitcoin and what books Zoltan is currently reading is available to download here.

Original source: ingoldwetrust.report

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.