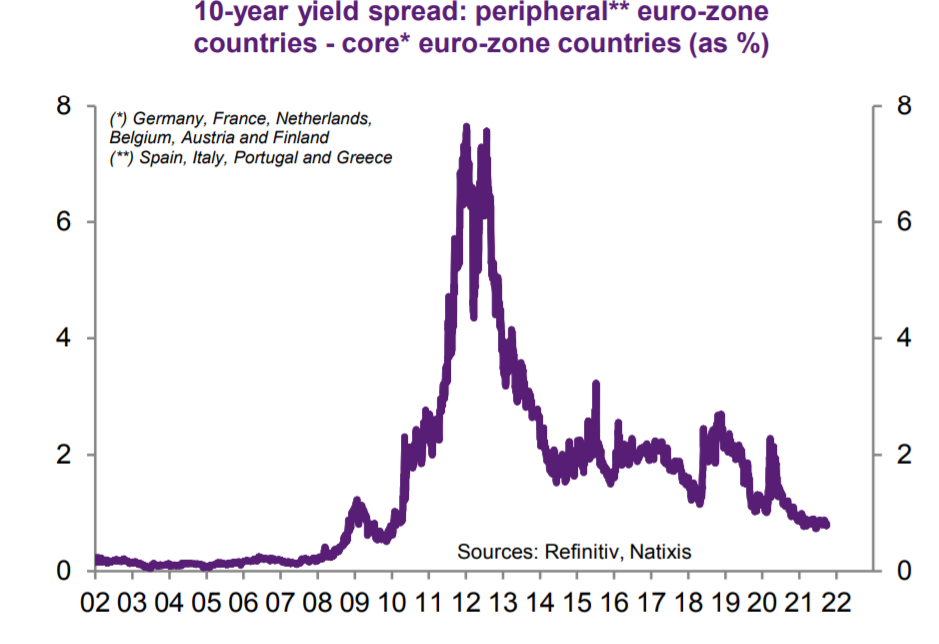

Everything seems to be going well in Greece, where the Prime Minister has just confirmed the purchase from France of twenty-four Rafale aircraft and three frigates, for a total of six billion euros. Has the country emerged from the public debt crisis it experienced in 2011? More generally, are the "peripheral" countries of the eurozone (Italy, Spain, Portugal, Greece), which were affected by the Greek crisis at the time, out of the woods? Do they no longer have to worry about debt problems?

When compared to the "core" countries of the European Union (Germany, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Austria, Finland), the "Club Med" countries seem to refinance themselves with the same ease: the interest rate differential between the two groups is less than 1%. We can clearly see the crisis of 2011 and, since then, a gradual reduction of this spread:

However, this good health and confidence of the markets turns out to be completely fake, as explained in the Natixis study from which this chart is taken: since 2015, most of the debt issued by these countries is bought by the European Central Bank (ECB)! Not crazy, private investors are turning away from it.

Admittedly, the debt of the core countries is also acquired by the central bank, but these countries benefit from good market confidence anyway, with the ECB's purchases just allowing - but it is already a lot - to lower the rate at which they refinance on the markets by several points. Without this help, France would be bankrupt. Borrowing at 4-5% would cause the debt burden to explode and the government budget would sink with no hope of returning to normal. France is slipping from the core of the eurozone to its periphery, and that's the problem. In short.

So the peripheral countries are still on life support, as they have been since 2011. Their apparent good health on the debt market is just an illusion. They suffer from structural problems (high public debt, low growth, failing modernization and innovation, low skills of the labor force) that should lead them to have to offer higher interest rates to refinance themselves. But this is not happening, thanks to the ECB.

This is hardly encouraging for the eurozone, although it is not a surprise. This situation could continue for several more years, except that a disruptive element has appeared: inflation. Christine Lagarde has just stated that the ECB should not "overreact" to the transitory effects on inflation. Of course, but in any case it can hardly act anymore. Because if it raises interest rates and/or if it stops buying government bonds (from peripheral countries and France), the eurozone will experience a worse crisis than in 2011, i.e. it will explode.

The ECB is building a Potemkin village of European public debt, to keep up appearances, hoping that inflation will not undermine the whole thing...

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.