A phenomenon that is unprecedented, to say the least, is currently taking place in many countries, particularly in the eurozone: several central banks have declared that they are under threat of heavy financial losses in the coming months and years. On February 23, the ECB (European Central Bank) announced that it had dipped into its reserves in order to avoid an estimated loss of 1.6 billion euros in 2022. This seems at first sight unimaginable: How can a bank suffer losses? How can it endure such a risk when its monetary power seems unlimited? How can it respond?

A company that finds that its equity is negative must quickly make a decision... a central bank, on the other hand, operates in a completely different way and can afford to stay that way continuously. Many central banks have already found themselves in such a situation (Chile, Switzerland, Slovakia, Israel, etc.). Today, several monetary institutions in the eurozone are concerned. Here are the reasons.

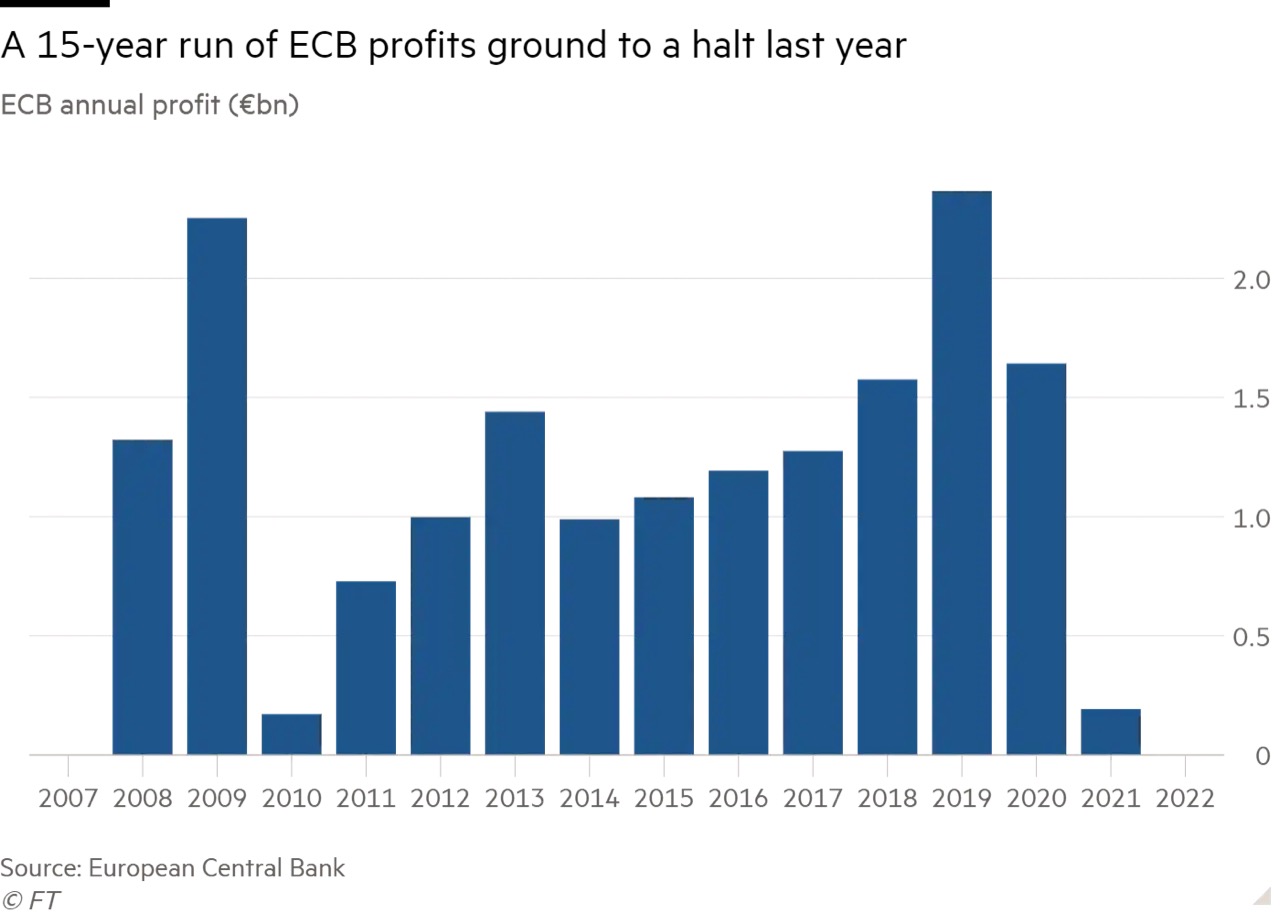

Since the introduction of an unconventional monetary policy in the eurozone, i.e., from 2008 and more intensively since 2014, the Eurosystem (the ECB and the national central banks) manages to make large profits and in different forms:

- Capital gains realized on the financial securities it holds on its balance sheet through its market transactions.

- Interest paid by debtors when central banks buy back their debt on the secondary market.

- Interest paid by commercial banks on their reserves with the ECB when rates were negative.

- Income on foreign currency reserves and investments (which is a very small part of its profits).

Once these profits are received, the ECB can decide to pay dividends to the various central banks of the eurozone (which correspond to its shareholders), or to keep them in reserves (which makes it possible to cover future losses).

The national central banks, on the other hand, being for the most part entirely government-owned, pay these dividends, but also their respective profits to the governments in addition to taxes (they may also keep a certain amount in reserves as the ECB does).

But after several particularly lucrative years, when money was "not worth much" and profits multiplied, the monetary institutions of the eurozone are now facing one of the consequences of their own policy. The ECB's interest rate hike to fight inflation is likely to result in heavy financial losses for the central banks.

Substantial losses

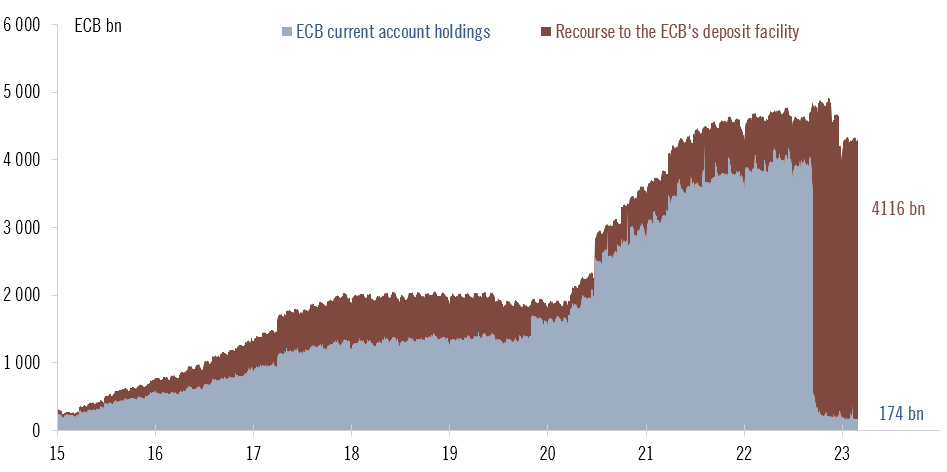

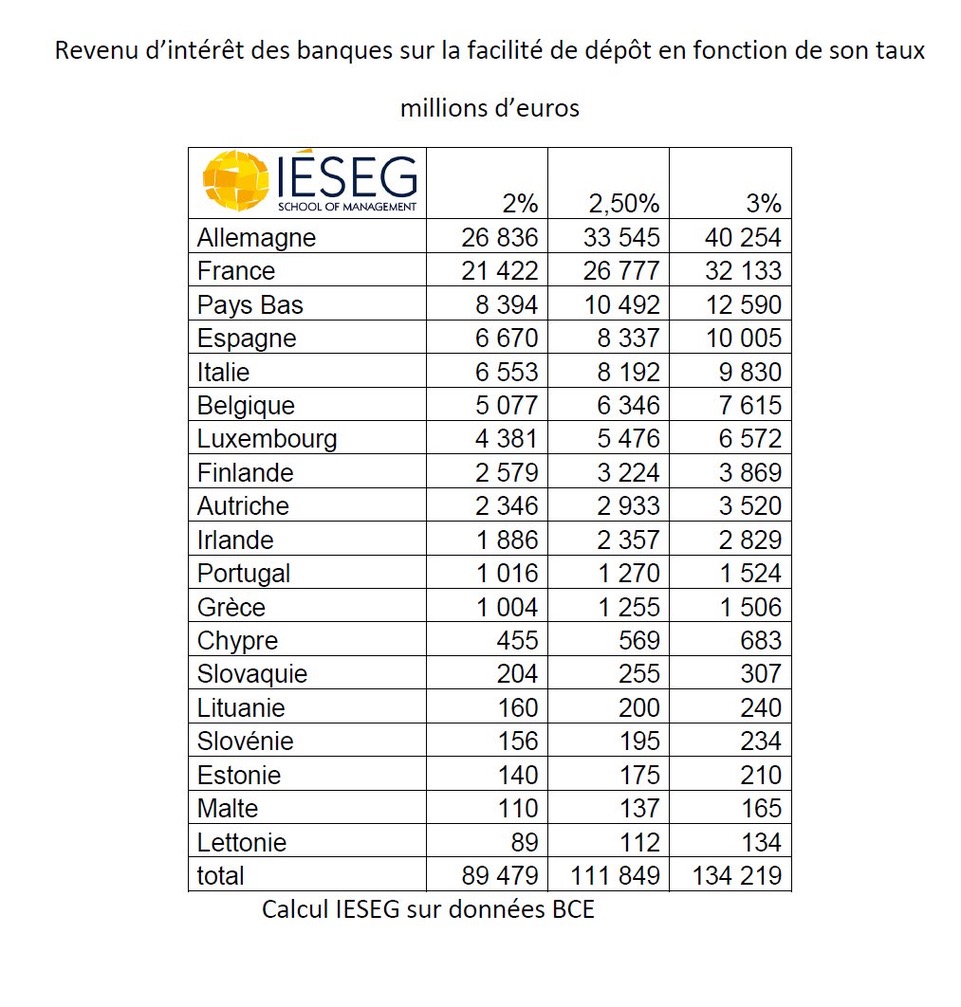

Not only are the financial securities they hold showing losses (some unrealized, others realized if the securities have reached maturity), but above all - and this is the main cause of their losses - they are forced to remunerate the savings of commercial banks placed with them, at the deposit rate currently set at 2.5%.

In fact, since the rise in interest rates, and the deposit rate by extension, banks have shifted the bulk of their reserves with central banks to their deposit accounts, allowing them to receive a particularly high return.

The total amount of these accounts is estimated at nearly 4,116 billion euros, mainly from long-term refinancing operations where banks have borrowed at negative rates. This represents an annual interest payment of 111 billion euros in 2023 if the deposit rate remains unchanged, 134 billion euros if the rate reaches 3%, and about 160 billion euros if it reaches 3.5% (equivalent to the European Union budget, equal to 168 billion euros).

While the ECB intends to continue its monetary tightening in the face of historically high inflation (8.6% in February), everything suggests that the amount of this interest will increase and accentuate the losses incurred by the Eurosystem.

Faced with this situation, the Frankfurt-based institution has already stopped paying dividends to national central banks. It has announced that it has drawn on its reserves to avoid a loss of 1.6 billion euros in 2022.

To reassure the markets and maintain its credibility, the ECB stated that the Eurosystem had set aside 116 billion euros in provisions and 113 billion euros in reserves and capital in recent years, before adding that its "net equity is sufficiently large to deal with any deficits".

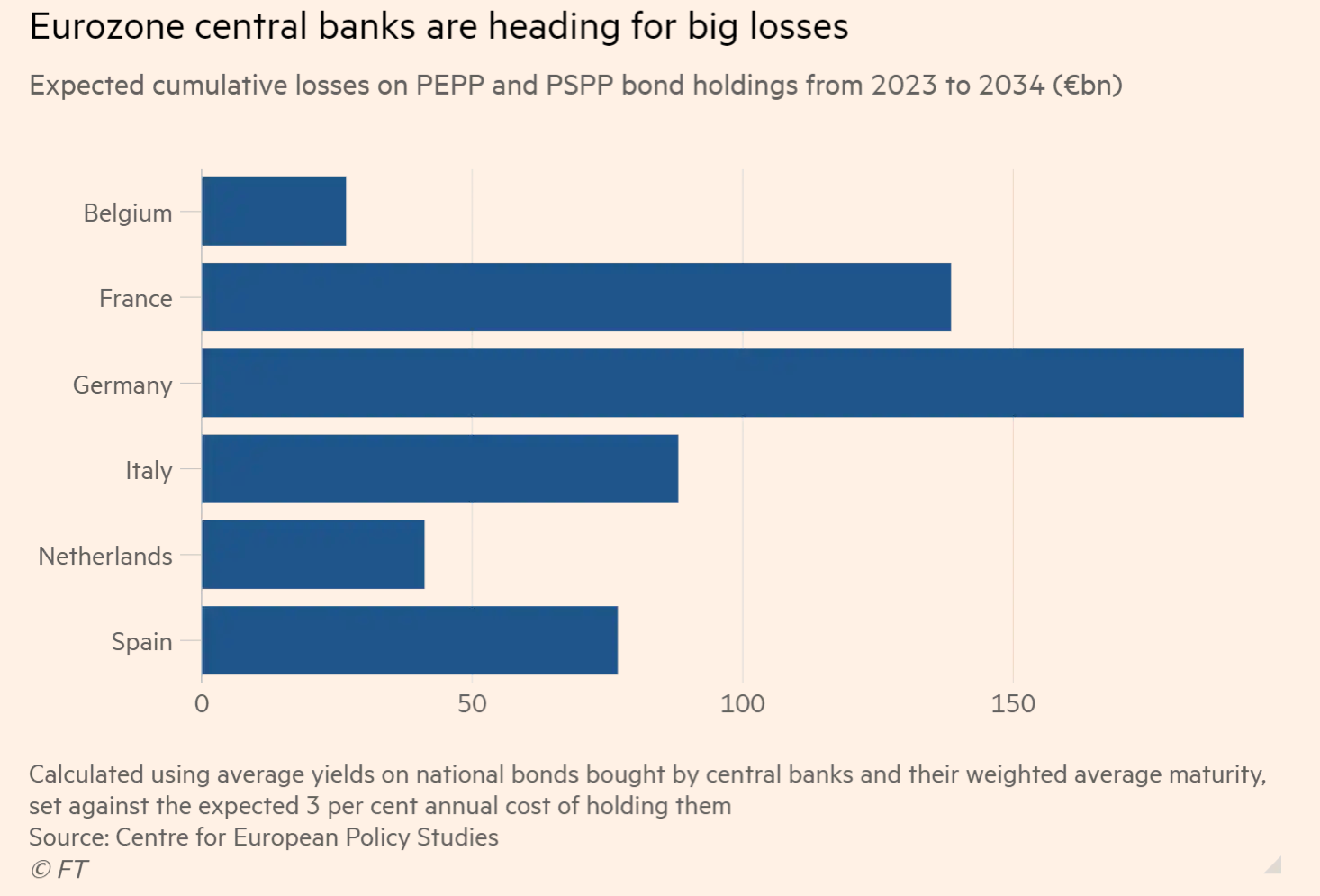

Nevertheless, depending on the estimated losses (on bonds and interest to be paid to commercial banks), all national central banks in the eurozone could quickly find themselves with negative equity. Some analysts even estimate that the total amount could reach 600 billion if the deposit rate reaches 3% and remains unchanged for the next six years.

A major political challenge

In fact, "The scale of the payout on deposits will drag many eurozone central banks into the red" says economist Frederic Ducrozet, before adding that they "could face growing political pressure to be recapitalized". While in theory a central bank can subsist with negative equity (through a process called "seigniorage": it accumulates a deferred asset until it regains profitability), this calls into question its credibility. This is particularly true in the eurozone, where there are many political and economic divergences.

Thus, the issue is as follows: either the ECB and the national central banks choose to continue with negative equity, at the risk of undermining their credibility at a time when they are trying to maintain it by fighting inflation. Or, they ask for a bailout from the governments, which would entail an additional expense for public finances at a time when the burden of their debt is constantly increasing. This could also call into question their independence...

The main risk to this dilemma lies in politics, and in particular the German position on the subject. With a public sector that is particularly hostile to the ECB's unconventional policies, and the numerous legal attacks in this regard over the past years, Germany is likely to be up in arms about this situation.

The Constitutional Court of Karlsruhe had formally refused to allow the Bundesbank to participate in asset purchase programs that expose it to the risk of losses... while the Bundesbank will quickly find itself with negative equity if one observes the estimates, despite the accumulation of nearly 20 billion euros in provisions in recent years. Potential losses are actually estimated at 193 billion over the next decade, more than all the other central banks in the eurozone.

According to the Financial Times, the President of the Bundesbank, Joachim Nagel, nevertheless tries to reassure that the German central bank has "little risk" of being confronted with such a situation in the short term because it has more than 3,350 tons of gold with a value of approximately 170 billion euros in Frankfurt, New York and London.

The Eurosystem faces complicated months

More broadly, this situation will be subject to growing political pressure from the various European countries and within the Governing Council. Especially since the pace of interest rate increases and the reduction of the ECB's balance sheet are causing many divergences... while long term rates on the markets are rising again due to a resurgence of inflation in Spain and France in February. The 10-year rate in France is now over 3.1%, in Italy 4.5%, and in Germany 2.7%.

The ECB could thus make further and larger interest rate increases in the months to come, leading to higher deposit rates and interest payments to commercial banks. On the markets, investors expect that the "peak" of interest rates in the eurozone will reach nearly 4% in the first quarter of 2024.

So this debate about central bank losses (which applies not only to the eurozone but to many countries in the West) shows us more than ever how much our system of unlimited debt is suffering. A new paradigm must be opened as soon as possible, where money creation would be rethought in depth to truly serve the productive economy and put an end to deadly investments.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.