The history of money is several thousand years old. But do we know its evolution? How was it created? How does it work? Its influence?

The questions that revolve around this social link are of little interest to the average person. Yet money structures our economic and political models.

In the classical sense of the term, it is an instrument of payment in force in a given place and time. According to Aristotle, it is a unit of account, a store of value and an intermediary for exchanges. Beyond these three functions, it is composed of a single aspect: trust. Money relies only on the trust of its users. Above all, money relies on the trust of its users, whether or not it is a value in itself. In a market economy, this is a fundamental element in the proper conduct of politics in the broad sense. To paraphrase Michel Aglietta - an illustrious 21st century economist - trust in money is the alpha and omega of society. The fact that the many inflationary and financial crises in history have been followed by large-scale reforms is therefore not surprising... Confidence was lost, and it had to be restored.

So why are the recent financial crashes an exception? What were the reforms of previous centuries? What were the dominant schools of economic thought? A brief look at the evolution of the monetary system, especially since the 19th century, will give us some answers.

Money throughout history

Currency has existed almost since the dawn of time, but has taken many different forms (salt, shellfish, livestock,etc.) throughout history. It first became a metallic currency in the 7th century B.C. by Gyges, King of Lydia. Electrums (natural alloys of gold and silver) were used to trade goods and pay wages. Debt is preserved both as a source of financing and exchange, thanks to the circulation of debts.

Photos of electrum in 600 BC

The advent of metallic money marks a major societal change. "Struck" by the public power, symbol of the strength embodied by the city, this new tool serves to vivify the local retail trade and is accepted to pay taxes. In a period of emancipation of thought, its introduction allows an improvement of citizenship and an increased development of science. Moreover, it is a real economic and social innovation.

However, the fall of the Roman Empire and the advent of the Middle Ages altered the status quo. The establishment of feudal systems restricted freedoms and limited access to metallic money. To ensure that as many people as possible could continue to trade, new systems such as the counting stick and the bill of exchange were introduced.

Bartering was only marginally used at this time, in line with previous centuries.

Counting stick used in the Middle Ages

During the second half of the Middle Ages, the intensification of commercial exchanges accelerated the need for a practical means of exchange for all. Bi-metallic systems (gold/silver), and even tri-metallic systems (gold/silver/bronze) in the Muslim world, were used for the crusades and the expansion of trade. Under different names, a multitude of national currencies appeared - all of them referring to a specific metal weight. Devaluations were regularly established by simply reducing the weight of each currency.

The 12th and 13th centuries were then marked by numerous upheavals and an anthropological break. Time became man's business, no longer dictated by the Church but by merchants. Religious society gradually lost its power to mercantile society, and in particular to merchant-bankers like the Medici. Historians refer to this flourishing era as a "commercial revolution", with unprecedented technological innovations (water mills, compasses, mechanical clocks, etc.) fueled by a booming banking system. This was the birth of the stock market, futures, insurance contracts, public loans... and the gradual liberation of interest-bearing loans, still known as usury. Italy was at the heart of the world economy, represented by extremely powerful city-states such as Genoa, Florence, Venice, etc.

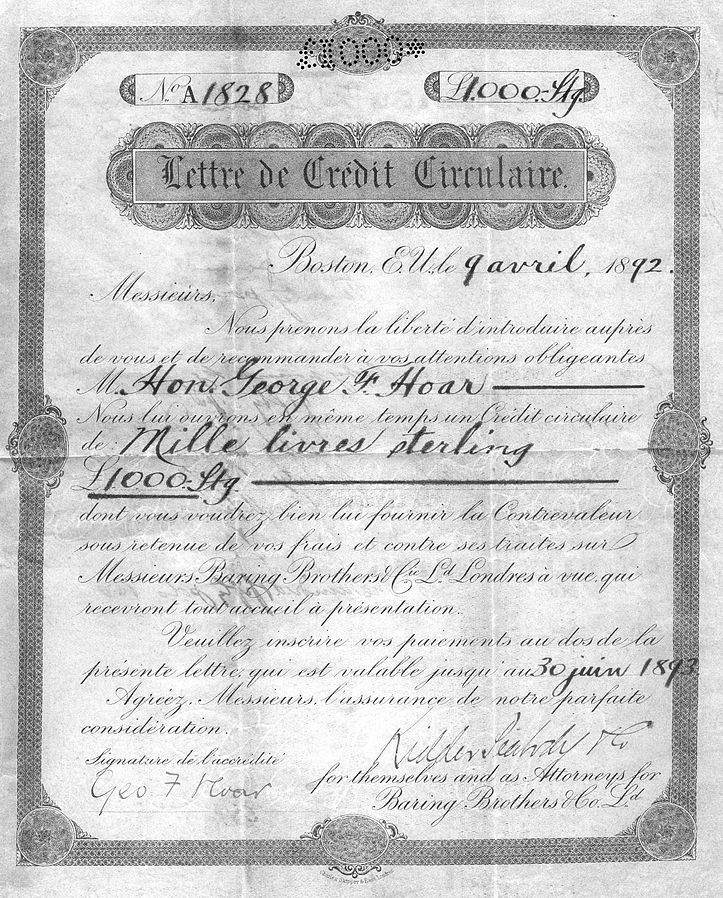

Bill of exchange, also called "circular letter of credit"

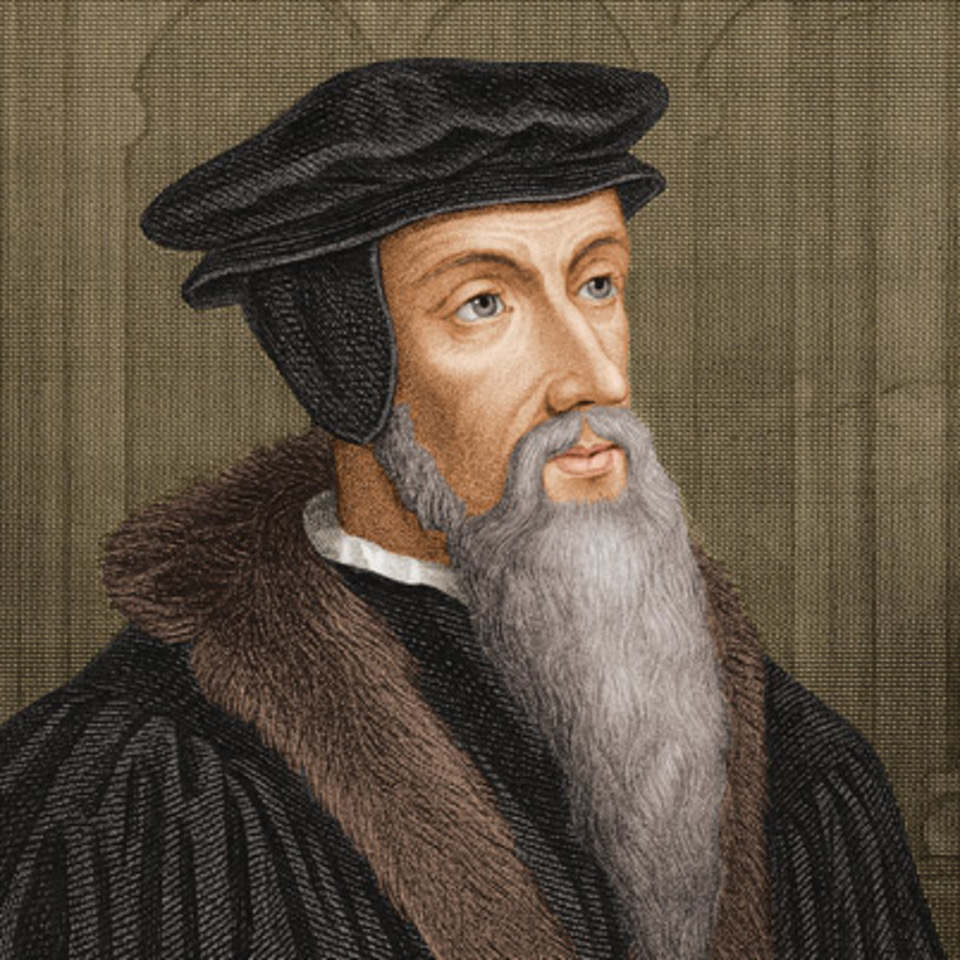

The 16th century accelerated this progression. Following on from the rupture orchestrated by the Middle Ages, the relationship between man and faith - and man and money - was seen in a new light during the Renaissance. In this period, marked by the development of the humanist movement, the intensification of religious reforms led to the politicization of currency and the emergence of mercantilist concepts. Following the birth of Protestantism in 1517, interest-bearing loans became widespread under the impetus of John Calvin.

John Calvin (1509 – 1564)

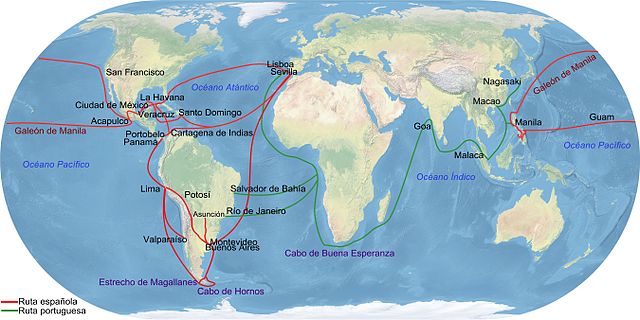

This period was also marked by the emergence of new economic cycles, the effects of which stirred up public debate. The discovery of America and its vast quantities of metals - at a time when metal currencies were still the main means of payment - generated a period of high inflation in Western Europe and China. Different currencies coexisted, and metal shortages coupled with this new abundance. Monetarist thinking took its first steps with Copernicus' famous declaration that "money depreciates when it becomes too abundant", which Jean Bodin - a French economist and philosopher - took up and developed in his "Réponse à M. de Malestroit", as did John Locke and Thomas Gresham, who both made similar statements.

Flow of metals in the 16th and 17th centuries

The financial changes of the next two centuries were to overturn these ideals. With the creation of deposit banks (represented by goldsmiths), the birth of central banks - then privately-owned -, the development of banknotes and the creation of the first international currency - the thaler (forerunner of the dollar) - the monetary system became more bankable. Known as "tulipomania", the first financial crisis linked to the rising price of tulips occurred in Holland in 1636.

New schools of economic thought took hold, and two in particular stood out when the Bank of England's suspension of the gold convertibility of banknotes in 1797 was followed by historic inflation two years later, and an economic crisis in 1810.

Represented by David Ricardo, the proponents of the currency school defended the idea that money should be issued on the sole condition that the central bank hold the equivalent in gold and silver. This monetary policy would not only make it possible to control inflation (and thus the loss of value of money), but also to create the conditions for a prosperous economy. In contrast, the proponents of the banking school - founded by the British economist Thomas Tooke - believe that the quantity of money in circulation should be decoupled from the holding of gold and silver and should refer only to economic circumstances. Bank loans can be issued in unlimited quantities, depending on the demand of economic agents.

Birth of the Gold Standard

In 1844, following the numerous financial crises of the early 19th century, the currency school prevailed when the last version of the Bank Charter Act was passed in England. Twenty years after Ricardo's death, the gold standard was adopted in the country. The value of each currency is then defined according to a weight in gold, and currency issuance becomes dependent on the gold reserves that central banks hold in their vaults.

David Ricardo (1772 – 1823)

Against the backdrop of a constantly growing globalization, the international community decided to ratify this unique monetary system. Most of the Western countries introduced it in 1873. India, Argentina and Russia did the same a few years later. The money supply and the exchange rate of each country were henceforth linked to gold movements. This means that their wealth is conditioned, to a lesser degree, to the distribution of yellow metal in the world.

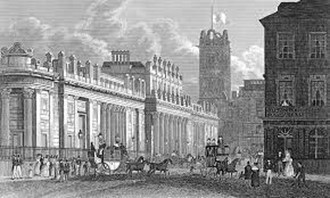

Inegalitarian by nature, this system was also highly unstable. As a growing number of countries joined the system, falling gold production feeds hoarding and generates cycles of falling prices. The hardest-hit countries experienced sharp rises in unemployment and productivity. Moreover, the United Kingdom - the decision-maker in the choice of this regime - wields a particular influence within the system. Benefiting from its industrial and financial strength, as well as its energy power thanks to its numerous coal mines, the country succeeded in imposing the British pound as the international reserve currency. In a way, the Bank of England was the world's central bank (as is the U.S. Federal Reserve today). A change in its key interest rate - which rises when gold is scarce - enabled the central bank to attract foreign capital. This status helped maintain the UK's position as the world's leading power for several decades.

Bank of England circa 1840

When the First World War broke out, the unsustainability of this system reached its peak. The financing of the war economy proves to be extremely expensive, and the yellow metal reserves of the belligerent countries are rapidly depleted. England, Germany and the United States decide to suspend the use of the gold standard.

While the economy is at a standstill, the abundance of money (banknotes and bank deposits), causes moreover a strong and durable inflationary period. (A situation that closely resembles the one in which we live following the crisis of the coronavirus...) The share of the metal coins in the total monetary mass decreases, gold and silver become mainly reserves of values.

1918 - 1939: Between the Struggle for Monetary Hegemony and the Search for a New System

A few years after the Treaty of Versailles, the United States then saw in this breach the means to impose their financial power. At the end of the Great War, the Wilson government demanded the repayment of the loans it had granted for nearly four years. This status as a creditor allowed the country to hold 45% of the world's gold stock after the war!

In contrast, the debtor countries paid a high price. Although France managed to reduce its debt thanks to a policy of devaluation in 1928 under the impetus of Raymond Poincaré, the situation in Germany was quite different. The Treaty of Versailles imposed the payment of the large sum of 132 billion marks to the war victors. Faced with this repayment and other structural problems, German Chancellor Friedrich Ebert decided to make continuous use of printing money. But the devaluation and acceleration of the circulation of the mark led to a loss of confidence in the currency. Hyperinflation was rife in the country. The Weimar Republic decided to create, with great difficulty, a new monetary unit: the reichsmark.

(In the face of a possible presentiment, a nuance is necessary: the rise of Hitler was not made in a context of hyperinflation, but because of a very high unemployment rate linked to the financial crisis of 1929. In 1933, when the Führer was appointed chancellor, unemployment reached 17.5%, whereas it had only been around 2% in the 1920s).

Castle of marks: German hyperinflation (1921-1924)

At the same time, under the initiative of the United Kingdom, the Genoa Conference was ratified in 1922. In order to restore an international monetary order, the 34 countries represented decided to return to the gold standard, where only the pound sterling and the American dollar were convertible into gold.

At a time when economic debate was gaining momentum, the return to the pre-war system generated much controversy. While advocating the idea of a sustainable and equitable regime, John Maynard Keynes declared the gold standard to be a "barbarous relic." He considered that the resulting scarcity of money could cause the economy to collapse.

For his part, the German economist Silvio Gesell denounced the deflationary effects of the gold standard and continued his fight for a melting currency: a system in which money that was not spent - over a long period of time - was taxed in order to be reinjected into the real economy. In these mixed times, Gesell saw a growing interest in his work. Detailed in his book "The Natural Economic Order", which he published during the Great War, his theory began to spread throughout the world. Keynes called Gesell "a strange prophet" and declared that "history will remember more of his ideas than of Marx's."

The status quo was maintained, however, until the onset of the financial crisis of 1929 - which signaled the abandonment of the gold standard. The effects of the "Great Depression" were unprecedented: unemployment and poverty soared, and the banking panic turned into a full-scale economic crisis. Economist Hans Cohrssen declared: "The technical difficulties of achieving monetary stability are minor compared to the overall understanding of the problem. Until the monetary illusion is overcome, it will be impossible to mobilize the political will."

Although Gesell died in 1930, his death was only physical, for his struggle was fiercely pursued by Cohrssen. After founding an association (the Free Economic League) dedicated to the publication of Gesell's ideas, Hans Cohrssen wrote a book in collaboration with the American economist Irving Fisher. In it, the authors put forward the monetary policy inspired by Gesell and the way in which it could be implemented. This legacy of thought, which was constantly growing, contributed to the first experimentation with fiat money in the Austrian village of Wörgl in 1932. The introduction of this local currency was a great success. Economic activity was excellent and unemployment was reduced by 20% within a year. The inhabitants of the neighboring towns were amazed and decided to replicate the concept. The movement spread throughout the world: 450 American mayors said they were ready to use it. But this new monetary policy soon came to an end. The Austrian central bank judged that its use would be detrimental to the sovereignty of the shilling and decided to ban it, without even thinking about it. The introduction of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1933 (a far-reaching financial reform) overturned the American financial system and thus put an end to the idea of a new monetary concept on the other side of the Atlantic.

Gesell's thinking remains, even today, unfinished. Will it ever be revived?

Silvio Gesell (1862 – 1930)

During the Second World War, the United States relied on its military-industrial complex to sell weapons and munitions on a massive scale in exchange for gold bullion, which it continued to accept. In 1944, the country had 70% of the world's gold stock, 25% more than in the aftermath of the Great War. This dominant position, combined with a large capital market and a powerful army, allows the United States to lead the the Bretton Woods Conference (a conference supposed to rebuild a sustainable international monetary order). On July 22, 1944, a gold standard system favorable to American interests was decreed. The value of the dollar was indexed to the price of gold, while other currencies were indexed to the dollar. In other words, the monetary stability of a country requires the acquisition of American currency.

Bretton Woods Conference in 1944

Aware of the iniquity of this regime, General De Gaulle denounced its instrumentalization by the United States. After explaining that the return to the gold standard made it possible to prevent states from giving in to "the deceptive delights of money creation," the general declared, during a conference given at the Élysée Palace in 1965, that this new regime allowed "the United States to indebt itself freely to foreigners." Sixty years later, the US debt exceeds 30 trillion dollars...

Faced with Triffin's dilemma (1) and the depletion of yellow metal resources, U.S. President Richard Nixon decided to end the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1971. The gold standard was definitively abandoned.

Central banks and private deposit banks now create money ex-nihilo (out of nothing), without having to refer to the quantity of gold they hold. The hegemony of the dollar continues, albeit in a different form.

The world's monetary system was based on confidence in the American currency and the country's military and nuclear power. The FED became the world's central bank, just as the Bank of England had been a century earlier.

Gradually, the main central banks became independent. This means that money is created, out of thin air, in potentially unlimited quantities, without any direct public decision.

One dollar bill

In view of the current period, a return to economic history is more necessary than ever to think about the system of tomorrow. The singularity of the system that has prevailed since 1971 shows us - more than ever - that economics is an inexact science. The same system that generated exponential growth in the money supply is now faced with high inflation, the direct and indirect consequences of which are dramatic.

The wait-and-see attitude of monetary institutions to raise interest rates is closely linked to the fear of economic collapse, which dates back to 2007-2008. This is because a rise in interest rates will ultimately trigger a major financial crisis. Unless central banks allow inflation to continue, in which case the currencies of the major powers will be worthless.

At the end of this cycle, the great challenge is to know whether we will be able to draw inspiration from past and forgotten proposals, such as those of Gesell, or from new ones that are the fruit of collective intelligence nourished by the spirit of justice, in order to build a sustainable monetary system. Or will we simply choose, as we too often do, denial and obstinacy? History is watching and will not forget us.

Notes :

- Triffin's dilemma is an economic paradox that holds that the country whose currency is the international reserve currency must necessarily have a permanent trade deficit for non-resident economic agents to hold its currency.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.