In his book L’or des Français (The Gold of the French), published in 2024, Yannick Colleu offers a reinterpretation of the actual gold reserves held by the French. Between wars, demonetization, exports, and resales, the actual gold reserves held by the French remain unknown. Nevertheless, some estimates can be made based on the main events that have contributed to the evolution of gold reserves over more than two centuries.

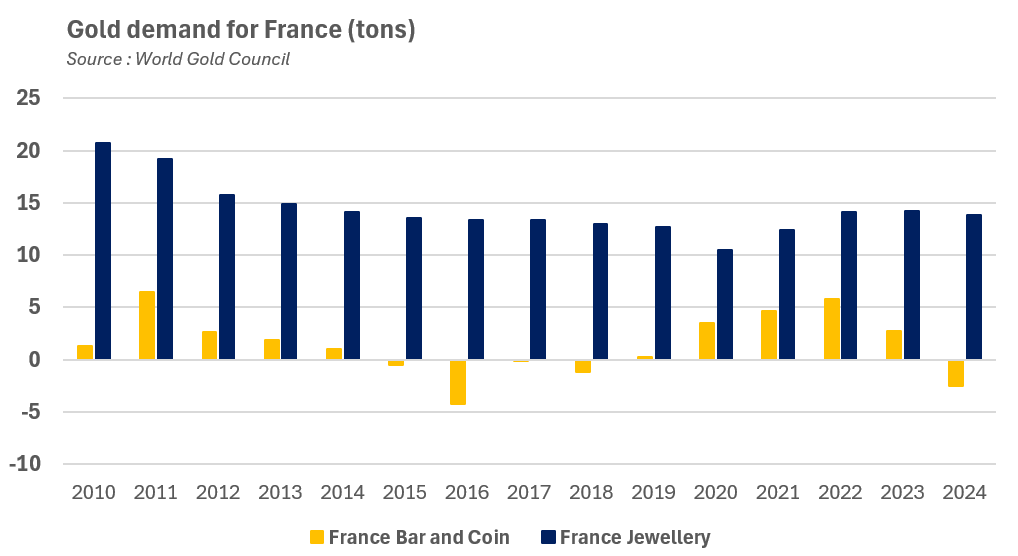

While the French have purchased nearly 240 tons of gold over the past 15 years, barely 9% of these purchases were in the form of coins and ingots, according to the World Gold Council. In fact, the French were even sellers of investment gold in 2024. Furthermore, the French appetite for gold remains moderate, with their German and British neighbors demanding up to 2.5 times more.

In this context, how can we define and estimate the French gold stock to date? I had already published an article on the subject a few years ago, but this one proposes to take a more critical approach based on the work of Yannick Colleu.

The origins of French gold

Many French people may have already forgotten this, but gold coins were common currency just a century ago. Gold circulated as a means of payment, but until the mid-19th century, it was still relatively rare in everyday life. In fact, most of the gold issued in the form of coins was minted under Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte and the Third Republic. In total, between 1803 and 1921, it is estimated that coin issues amounted to around 3,500 tons of gold. More than 80% of these issues were concentrated between 1850-1880 (48%) and 1895-1914 (34%).

As a major center of the gold market in the 19th century, Paris received large flows of gold from Australia, South Africa, the United States, and Russia, which fed reserves and covered monetary issues. In the second half of the 19th century, France effectively accumulated trade surpluses with other European states, enabling it to build up significant gold reserves. In fact, France accounted for more than 80% of the currency in circulation in the Latin Union, the distant ancestor of the euro.

The accumulation of gold in France was therefore mainly the result of the exploitation of new gold deposits and the country's commercial power during the second half of the 19th century. France abandoned gold in 1936, following in the footsteps of Great Britain and the United States a few years earlier, and under pressure from continuous devaluations. At the end of the 1930s, France held an exceptional stockpile that represented nearly 10% of the world's official gold reserves at the time. The Banque de France is believed to have held up to nearly 4,800 tons of gold in its vaults around 1933, compared to around 2,400 tons today.

Historical accounting of French gold reserves

According to Yannick Colleu, “the answer to the question of the maximum volume of gold savings held by the French public in 2024 can therefore be summarized in three responses: between 600 and 700 tons of French gold coins; between 15 and 20 tons of foreign gold coins; and an unknown volume of gold bars.”

In fact, from the 3,700 tons of gold put into circulation between 1803 and the 1920s, we must subtract just over 800 tons of official demonetization. As for definitive gold exports, these are estimated at 400 tons. This would bring the “official” gold stock to around 1,600 tons at that time. The task then becomes more complicated.

The archives of the Banque de France show that the gold stock of French coins around 1928 was probably close to 1,376 tons, from which 726 tons of demonetizations must be deducted until 1960. This brings the theoretical stock to around 960 tons of gold for the year 1960.

In fact, the Banque de France archives show that the gold reserves of French coins held by the Caisse Générale amounted to 867 tons in 1960, of which 800 tons were held by the public. This figure therefore seems fairly consistent with the sum of issues, demonetizations, and exports. The difficulty then lies in estimating the wear and tear these coins have undergone over more than 50 years. Based on the assumptions made, the author estimates that the stock of French and foreign gold coins potentially held by the public would be around 700 tons at most in 2024.

In reality, this stock could be even lower for two reasons. First, we must consider the historical events that led to unaccounted-for losses of coins. Second, we must factor in gold transactions carried out by individuals based on the latest estimates of gold coins held in 1960.

The default on Russian loans

Many events may have contributed to official demonetization. Economist Léon Say estimates, for example, that the defeat of 1870 cost France nearly 300 tons of gold in reparations. But on top of that were losses linked to financial disasters.

France is said to have lost a significant amount of gold when Russia defaulted in 1917. These loans, which were very popular with the middle classes and widely supported by the press, were in fact a bad deal for nearly a million French people. Up to 80% of Russian loans were reportedly taken out by French citizens, representing up to 9 billion gold francs according to the December 1919 census, and mobilizing up to a quarter of French savings invested abroad.

There is no clear estimate of the tonnage definitively lost by France. But the moral damage was very real. In the newspaper Le Démocrate de Seine-et-Marne of May 24, 1922, we read, for example, about a case of suicide by drowning: “The brave Mr. Rayer, from Jouy-sur-Morin, could not console himself for the loss of Russian funds, which had left a significant hole in his modest income. He had announced on several occasions that if all hope of receiving his coupons was lost, he would end his life, unable to return to work at the age of 82.”

The difficulties of the two war

The First World War marked a turning point in French gold holdings. Because, in truth, there can be no war without strong currency. War was declared on August 3, 1914, and just two days later, banknotes were made legal tender, preventing them from being converted into gold. In 1915, the famous poster by poster artist Abel Faivre proclaiming “VERSEZ VOTRE OR” (“Hand in your gold”) was printed in large quantities.

This appeal to the public to exchange their gold for banknotes, i.e. “public debt,” brought in up to 700 tons of gold to the Treasury. However, this was largely consumed by war expenditure, compounded by losses linked to the trade deficit, which led to the departure of nearly 900 tons.

As these banknotes were naturally insolvent, the massive devaluation of the franc in 1928 completed the withdrawal of this gold stock from the public. While the Germinal franc corresponded to approximately 0.290 grams of gold, the new implicit parity was close to 0.065 grams of gold, representing a loss in value of around 75 to 80%. The stabilization of the franc also encouraged gold purchases by the Banque de France between 1926 and 1928, estimated at nearly 230 tons.

World War II also had an impact on France's gold reserves. Estimates, such as those by René Pupin, show that World War II may have led to the theft of around 100 tons of gold. Yannick Colleu also points out that, as soon as they arrived in Paris, the Germans set up an authority responsible for registering all establishments that potentially held gold.

Pierre-Eugène Fournier, Governor of the Bank of France (1937-1940)

But the flight of the Banque de France's gold reserves, miraculously organized by Pierre Fournier and anticipated for several years by the melting down of coins to facilitate their removal, made it possible to save most of the public gold reserves. According to sources, these episodes between the two world wars led to the melting down of up to 1,330 tons of gold between 1934 and 1948.

French gold reserves: what do the polls say?

There are two ways to estimate a country's public gold reserves. The first method is to “start from the top,” i.e., to estimate the potential gold reserves of French citizens based on the figures available to us. A second method is to use “sampling” via surveys.

A 2014 Ipsos survey revealed that 16% of French people own or have owned gold. Specifically, 12% of French people reported owning gold in 2014. The survey also revealed that buyers tend to hold onto their gold for a particularly long time: 80% received gold as an inheritance, and 70% of holders have owned gold for more than 10 years. It is also noteworthy that gold is held by all social categories, since “10% of people with modest incomes currently own gold, 11% of workers, 12% of employees, 13% of executives, and 13% of people with the highest incomes.”

Based on the assumption that 12% of French people still hold gold today, this would represent, with 700 tons of coins, approximately 85 grams of gold per person holding gold, or the equivalent of a dozen 20-franc Napoleon coins. While this figure may already seem high, it should be remembered that we do not know how much gold is held in the form of jewelry or ingots.

Demand for investment gold remains low in France

France is rather a poor performer when it comes to gold investment. According to the World Gold Council, France has added around 240 tons of gold to its reserves since 2010, largely in the form of jewelry. Demand for coins and bars fluctuates between buying and selling. However, this figure remains fairly low compared to Germany and the United Kingdom, which are estimated to have added 1,850 and 500 tons of gold to their reserves over the same period, respectively. Germany shows a clear preference for investment gold over jewelry.

Indeed, if we estimate that the annual gold repurchase rate is close to 2%, it is possible to assess the stock of coins and ingots available to the French. This rate would imply a renewal of stocks every 50 years, which would be consistent with the idea that 80% of French people inherit gold (meaning that 20% of gold would change hands per generation over a period of around 20 years).

Considering a transaction flow of three tons per year and a redemption rate of 2% for France, the stock of gold in the form of coins or bars could be between 100 and 200 tons, at a minimum. Applying the same reasoning to jewelry, with an average flow of 15 tons per year, for example, would bring the stock in the form of jewelry to 700 or 800 tons. We would then find ourselves with figures similar to those developed by Yannick Colleu, with the difference that this gold would be largely in the form of jewelry. This point remains a particularly embarrassing unknown.

Nevertheless, this highly theoretical reasoning has a weakness. Apart from transactions that would be more frequent among our German or British neighbors, this would imply that countries such as Germany or the United Kingdom would have private gold stocks two to four times greater than those of France.

Conclusion

While we know that the Banque de France holds around 2,400 tons of gold, it is difficult to estimate how much is held by the French public. The end of gold convertibility, followed by the definitive abandonment of the gold standard in 1971, put an end to regular monitoring of stocks in circulation. Nevertheless, reconstructing major historical events makes it possible to refine these estimates.

In his book L'or des Français (The Gold of the French), Yannick Colleu estimates the maximum gold stock held by the French in the form of coins at around 700 tons, excluding jewelry and ingots. Obviously, this estimate may seem low in view of the cumulative volume of monetary issues and the massive accumulation of gold by France between the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Nevertheless, demonetization and a series of military, financial, and geopolitical events led to a large-scale disposal of this gold. In particular, the two world wars contributed to significant losses in the stock held by the public. As a result, it is likely that the French gold stock has been significantly reduced over time.

The French interest in gold remains far below that observed in Germany, Switzerland, or the United Kingdom. It appears that the French prefer gold in the form of jewelry. While gold remains primarily associated with inheritance, it is nevertheless attracting growing interest in a context where building a robust and sustainable wealth base is becoming increasingly complex.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.