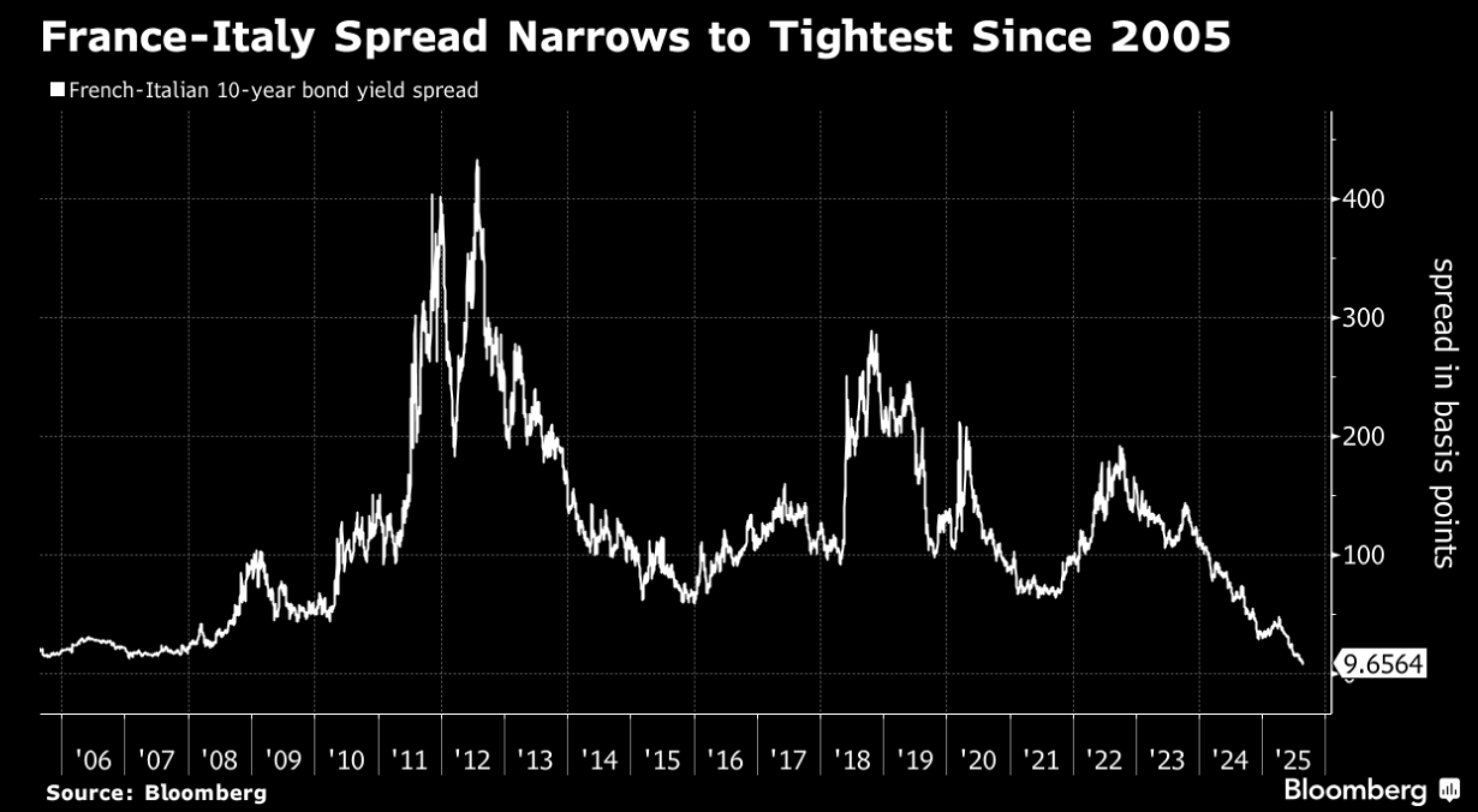

On September 8, the French government will face a decisive confidence vote. The uncertain outcome of the vote comes at a time when tensions are already visible on the bond market. French 10-year yields are now trading at the same level as those in Italy, something that has not happened since 2005.

This convergence is highly significant: traditionally, government bonds issued by the French Treasury (OATs) have enjoyed a credibility premium that clearly distinguishes them from Italian BTPs, which are considered riskier. This premium is now disappearing, a sign that investors are beginning to place France in the same category as peripheral issuers. At the same time, the yield spread with the German Bund – which serves as the absolute benchmark for the eurozone – is widening rapidly and heading toward levels reminiscent of the early stages of the sovereign debt crisis.

In other words, the market no longer sees France as a fully-fledged “core zone” country, but as a country sliding toward the periphery, with increased financing risk.

In the eyes of the markets, France now appears to be the weak link in the core of the eurozone. An unfavorable or simply unclear political outcome today would be enough to trigger immediate mistrust.

A French bond crisis would unfold much more quickly than the Greek crisis in 2011. The difference lies in scale and financial structure. French public debt exceeds €3.4 trillion, or nearly 30% of the eurozone's total debt stock, with refinancing needs of more than €300 billion per year. Unlike Greece, which accounted for less than 3% of eurozone GDP in 2011, France is a key issuer: any financing incident immediately affects the credibility of the euro as a whole.

The French banking system acts as a risk multiplier: its balance sheets are loaded with OATs, with leverage far greater than that of US banks, and its liquidity is heavily dependent on the interbank market and sovereign collateral. If OATs were to be refused as collateral in repos, the daily liquidity of the French banking system would grind to a halt. In such a context, a bond crisis would not remain confined to the debt market: it would quickly turn into pressure on the banking sector. The first signs of nervousness are already appearing. At the start of this week, French banks are falling on the stock market, with BNP Paribas and Société Générale leading the way. But we need to put this into perspective: these stocks, like the sector as a whole, are coming off an exceptional year, buoyed by rising interest margins and solid half-year results. The Euro Stoxx Banks index, after gaining nearly 70% since January, has begun a short-term correction.

The recent red candle illustrates profit-taking rather than widespread panic, but it highlights the sector's sensitivity to bond market tensions. However, the slight widening of bank CDS spreads and the euro's decline against the dollar signal that investors are beginning to test the system's resilience. The correction remains limited for now, but it highlights the structural vulnerability of French bank balance sheets to any mistrust of sovereign debt.

In the event of significant tensions on the French bond market, the most likely scenario remains that of ECB intervention. But this time around, the operation is much more difficult than it was for Greece or Italy in 2011.

To calculate what an ECB intervention on French debt would represent over six months, realistic estimates must be made. France currently has more than €3.4 trillion in public debt and an annual refinancing requirement in the medium- to long-term segment of around €320-350 billion, to which must be added a high stock of short-term Treasury bills (BTFs) that are constantly being rolled over. Over a six-month window, this typically means €150-180 billion in OATs/BTFs to be issued or rolled over in the medium to long term, and around €100-150 billion in BTFs to be rolled over through weekly auctions. In a stress situation, if market demand contracts by a third to a half, the “gap” to be filled by a buyer of last resort can very quickly reach €80-120 billion over six months just to stabilize the OAT curve, not counting daily short-term liquidity.

Compared to previous cases, the scale changes everything. The two Greek programs of 2010-2012 totaled around €240 billion in official aid over more than two years, via the EU and the IMF, while the ECB's direct purchases at the time (SMP) peaked at around a few hundred billion for all peripheral countries, including Italy and Spain. In a French scenario, “median” support from the ECB equivalent to €25-35 billion per month to cushion six months of tension would already represent €150-210 billion in OAT purchases, i.e., the order of magnitude of a Greek plan... condensed over a six-month period and concentrated on a single issuer in the core of the zone. A more defensive scenario, in which the ECB would have to cover half of net issues and secure the rollover of BTFs during difficult weeks, would easily push the total to €200-250 billion over six months, in parallel with targeted liquidity operations for banks (LTRO/TLTRO) in order to maintain the acceptance of sovereign collateral.

This is precisely where such intervention would be more difficult than in 2011. First, because of the absolute size: supporting France, the second pillar of the euro market, means accepting monthly amounts that rival quantitative easing, even though the ECB is in the process of tightening its balance sheet. Secondly, in terms of relative proportion: concentrating €150-200 billion of purchases on OATs in six months would significantly distort the allocation key, at the risk of being perceived as quasi-direct monetary financing of a state, which is legally and politically questionable in Germany and the Netherlands. Finally, in terms of financial transmission: French banks hold a lot of OATs with higher leverage than their US counterparts; if the ECB were to focus “only” on the primary/secondary markets without also easing the repo pipeline, pressure on bank liquidity would remain high. In summary, to stabilize six months of stress in France, we are likely talking about a package combining €150-200 billion in OAT purchases and generous liquidity facilities, i.e., firepower that exceeds, over the period, the scale of a peripheral country in 2011 and brings the intervention dangerously close to the red line of budgetary financing.

Supporting France could therefore potentially mean absorbing €150 to €200 billion in OATs over a six-month period, amounts equivalent to two Greek bailouts condensed into six months and concentrated on a single issuer!

Such an intervention would distort the allocation key for purchases, undermine the ECB's legal credibility, and be politically contested by Germany and the Netherlands, which would denounce it as disguised monetary financing. In practice, acceptance of such a program could only come with strict budgetary conditions, i.e., austerity measures imposed on France in exchange for Frankfurt's support.

This is exactly what happened in Italy in 2011, when Silvio Berlusconi, weakened, had to give way to Mario Monti, a technocrat supported by Brussels and tasked with implementing an austerity plan. But the comparison has its limits. In France, the prospect of a “French Monti” faces a much more explosive social context. A national strike is already planned for September 10. If the streets paralyze the country at the very moment when the bond markets are going haywire, any attempt at budgetary supervision would become politically untenable. Unlike Italy, France cannot count on parliamentary consensus or social resignation. The strike would prevent the rapid installation of a technical government and would expose the fragility of an executive imposed from outside.

In such a scenario, austerity would not be decided by a legitimate government, but imposed by the markets and technical administrations.

But what does that mean in practical terms?

Bercy would freeze credits and defer payments to avoid default, while the ECB would make its support conditional on budgetary commitments that no one would have the political legitimacy to endorse. Brussels could impose tighter supervision and dictate a numerical framework, but its implementation would be chaotic. This would result in imposed and improvised fiscal austerity, which would further fuel social unrest.

If the social deadlock continues, two extreme outcomes could emerge:

- The first would be one of de facto austerity: unable to borrow normally on the markets, the government would be forced to slash its spending. This would result in delays in the payment of public sector salaries, the freezing of certain investments, and the deferral of social security benefits. In this scenario, austerity would no longer be a political choice but a reality imposed by financial constraints.

- The second outcome would be a major political crisis. Faced with the impossibility of forming a credible government and containing the protests, the President could decide to dissolve the National Assembly in an attempt to restore legitimacy through the ballot box. But such a dissolution would take place in a climate of financial and social panic, which would make the outcome of the election uncertain and risk further instability.

The risk is therefore clear: if the government fails on September 8 and the general strike brings the country to a standstill, France could plunge into a systemic bond and banking crisis within a matter of days, with no credible political support to implement the budgetary discipline demanded by the ECB and the EU. This would be an unprecedented scenario: the de facto placement of the heart of the eurozone under supervision, but without the political instruments to make it viable. The contagion would immediately spread beyond France's borders: the markets would test the United Kingdom, still weakened by the precedent of the Gilt crisis in 2022, and Japan, whose rates are already under pressure.

The central scenario remains that of rapid intervention by the ECB to contain spreads. But the scale of the French problem – €3.4 trillion in debt, €300 billion in annual refinancing, a banking system with excessive leverage – makes this intervention much more difficult to calibrate and legitimize than in the past. If political and social conditions prevent any orderly supervision, there is a risk of austerity imposed by financial constraints, amid political and social chaos. It is this combination of political instability, bond market fragility, banking vulnerability, and social unrest, that makes France a unique systemic risk in Europe today.

We are not facing a certainty, but a growing risk. In the central scenario, France would experience strong bond market tension, which would undoubtedly be quickly contained by the ECB. But in an environment where markets are scrutinizing the slightest flaw, the vote on September 8 and the parallel national strike create a dangerous window of opportunity.

A French bond crisis could unfold much more rapidly than the Greek crisis in 2011, because the amounts involved are larger, French banks are more exposed, and the bond crisis would immediately spread to Japan and the United Kingdom.

In such a context, safe-haven assets – physical gold and silver – regain their full significance. They do not depend on the solvency of a state or the soundness of a banking system, and offer a tangible bulwark against an environment where liquidity can disappear in a matter of hours.

Gold priced in euros is currently trading in a pivotal zone. Since the beginning of 2025, the yellow metal has been consolidating in a bullish flag pattern, which is classic in a strong uptrend.

After the spectacular surge in 2024, which saw prices rise from €1,800 to over €3,000, the market entered a consolidation triangle with gradually narrowing boundaries. We are currently testing the lower boundary of this flag, a major technical support level. As long as this threshold holds, the configuration remains positive and suggests a new upward leg in the coming months.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.