The stress observed in cryptocurrencies and silver is not a mere epiphenomenon: it is the first sign of a market regime that is beginning to strain beneath the surface.

Bitcoin has returned to test a support zone that has been tested since 2024, around $70,000, while Ethereum is undergoing a much more severe correction—a classic sign of deleveraging that primarily affects the most leveraged segments.

This decline is not abstract: it is already beginning to put pressure on certain players. Michael Saylor's company, Strategy, finds itself automatically underwater on some of its recent purchases, made at significantly higher levels. At the same time, more fragile players in the sector, such as BitMine Immersion Technologies, are seeing their business model directly threatened by the combination of a declining bitcoin, high fixed costs, and more restrictive access to financing.

The case of BitMine Immersion Technologies perfectly illustrates the nature of the current stress on cryptocurrencies. Officially, the company is no longer just a miner: it has repositioned itself as a true “ethereum treasury,” assuming massive directional exposure to ETH. As Tom Lee pointed out, the stated objective is not to avoid volatility, but to ride it out, based on the assumption that Ethereum underperforms in bear markets and then outperforms in the next bull cycle. In this logic, current losses are presented as unrealized, almost as a structural feature of the model.

The accounting reality is nevertheless brutal. BitMine Immersion Technologies now has several billion dollars in unrealized losses on its Ethereum holdings, with the cumulative value of the position falling by more than 40%. This point is crucial: even if the loss is theoretically “unrealized,” it immediately affects the company's financial credibility, its financing capacity, and its perception by the market. In a more constrained liquidity environment, the accounting distinction between realized and unrealized losses becomes secondary. What matters is perceived solvency and the ability to hold the position without being forced to sell.

This case highlights a broader phenomenon: part of the crypto ecosystem has been structured around effectively disguised leveraged balance sheets, which are highly sensitive to prolonged drawdowns. As long as prices rise and liquidity is abundant, these structures are perceived as visionary. When liquidity dries up, they become systemic points of fragility.

BitMine Immersion Technologies is therefore not an isolated accident, but an advanced symptom of a market where stress is not expressed primarily through a widespread crash, but through the gradual and silent pressure on highly exposed players, before any visible contagion to traditional markets.

Once again, the signal is clear: this is not a rejection of crypto as such, but a purge of leverage and liquidity, typical of phases where stress begins to rise in the system before reaching the core markets.

Another sector affected: silver. A Chinese fund that is very active in derivatives ceased operations on Friday, triggering a first wave of liquidations:

This was the UBS SDIC Silver Futures Fund LOF, whose listing was suspended by the Shenzhen Stock Exchange after a speculative surge completely detached its market price from its net asset value. This suspension acted as a brutal confidence shock: the problem was no longer the silver price, but the very ability to exit positions. Trapped in domestic products, many investors then sold what remained liquid—international futures, ETFs, derivatives—triggering a secondary panic and an extremely severe liquidity shock, unrelated to the actual physical demand for the metal.

On Thursday morning, silver underwent another correction. On the Shanghai market, a volume equivalent to nearly two years of global production was dumped on futures in a matter of hours. This type of movement is not fundamental: it is a liquidity shock.

Despite these liquidity shocks, the equity markets remain impervious for the time being. Short volatility continues to work: in concrete terms, investors and intermediaries sell volatility—via options, structured products, or systematic strategies—by betting on the stability of indices. With each attempt at tension, the VIX is sold, which mechanically compresses implied volatility, stabilizes prices, and encourages repurchasing of stock futures at the slightest weakness. This self-perpetuating mechanism creates the illusion of a solid and disciplined market. This is precisely where denial sets in: in the belief that this regime can indefinitely absorb liquidity shocks elsewhere, and that the stress observed in metals, cryptos, or certain credit segments can remain compartmentalized in the long term without ultimately contaminating the core of the market.

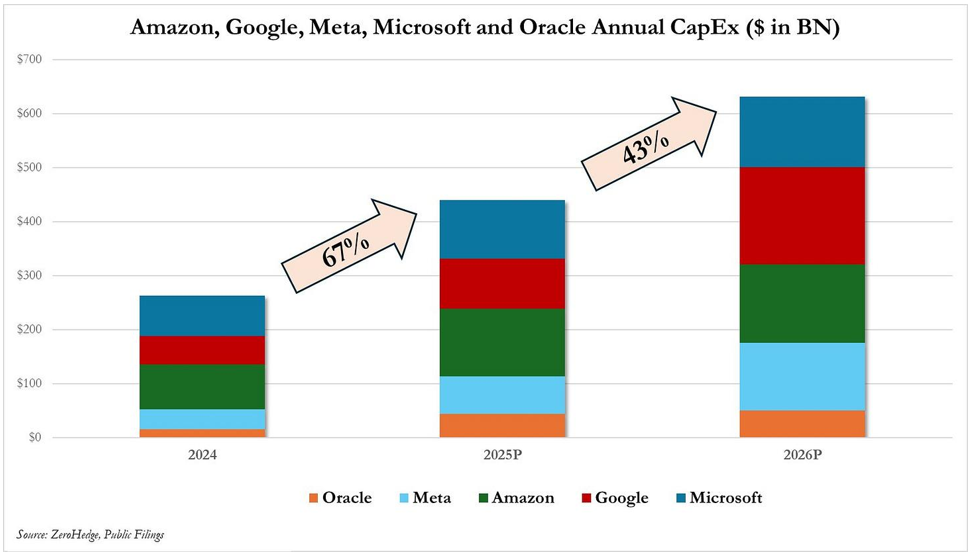

This same denial is at work on the central theme of AI and CapEx. The figures speak for themselves. The combined capital expenditures of Amazon, Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Oracle will rise from around $260 billion in 2024 to over $430 billion in 2025, then to nearly $620 billion projected in 2026, representing an increase of +67%, then another +43%.

We are no longer talking about a marginal adjustment, but a structural shift towards a heavy CapEx, industrial, energy-intensive model.

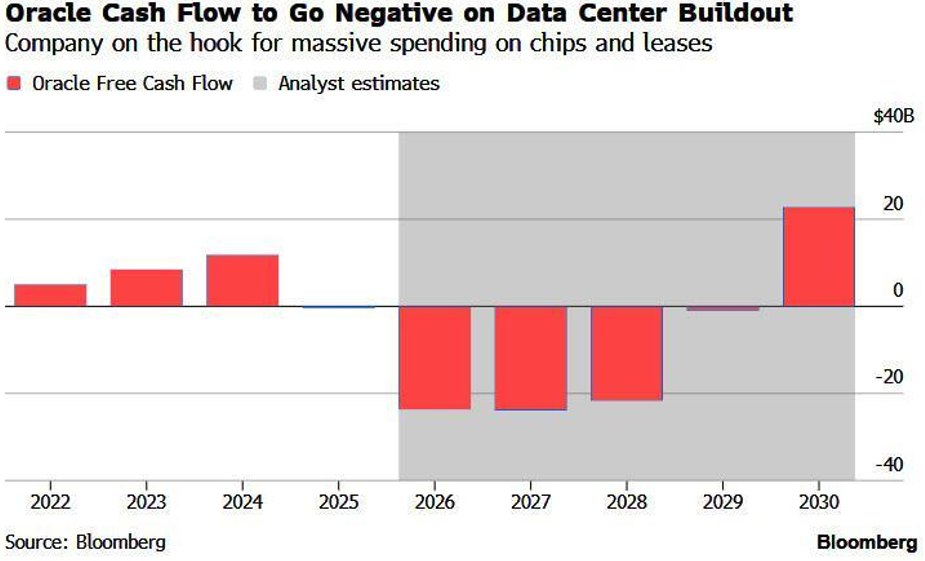

Oracle is the clearest example of this: the rise of data centers and commitments to chips and leases are pushing free cash flow into negative territory in several years:

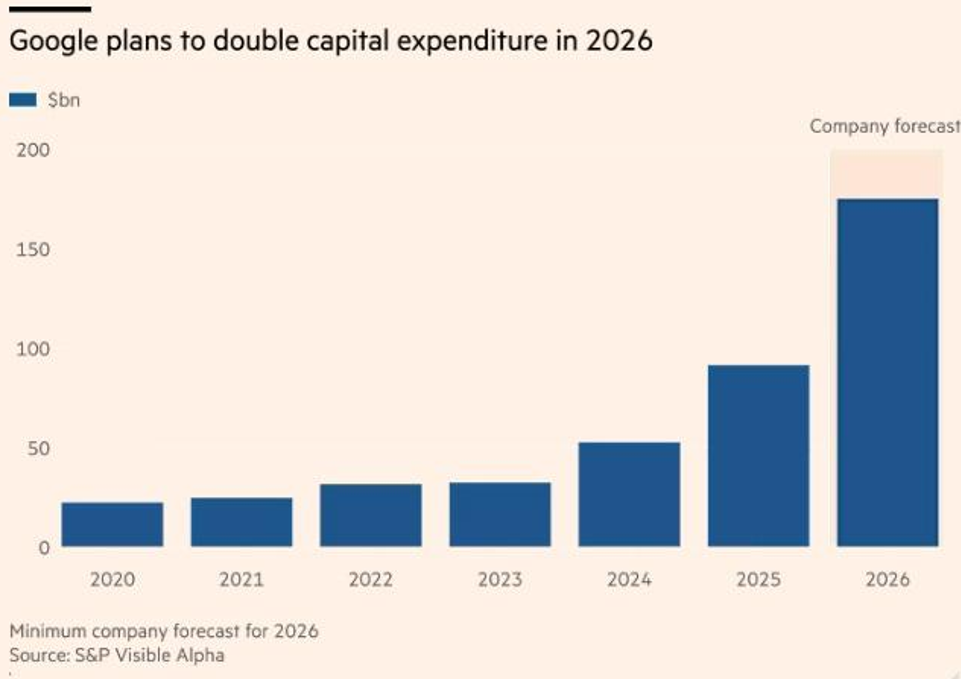

The same logic applies at Google. Behind the rhetoric of supposedly “software-based” AI lies an increasingly industrial reality. The figures speak for themselves. After annual CapEx remained below $30 billion between 2020 and 2022, Google moved to around $35 billion in 2023, then $55 billion in 2024. Projections point to nearly $95 billion in 2025, before a spectacular jump to between $170 billion and $180 billion in 2026—almost double in one year and more than six times the level of five years ago.

This trajectory is not theoretical: it reflects massive and very concrete investments in data centers, TPUs, cooling systems, infrastructure redundancy, and, above all, access to electricity.

This massive CapEx poses a simple problem that the market is still avoiding: the cost and availability of energy. The more power-hungry the models become, the more the electricity bill becomes a key factor in profitability. AI reintroduces an energy constraint into models that the market continues to value as if they were virtually immaterial.

AI is no longer a pure software product with incremental margins, but a heavy industry, constrained by network capacity, the price per megawatt hour, and the security of long-term electricity supplies.

It is precisely this structural transformation that the market continues, for the time being, to underestimate.

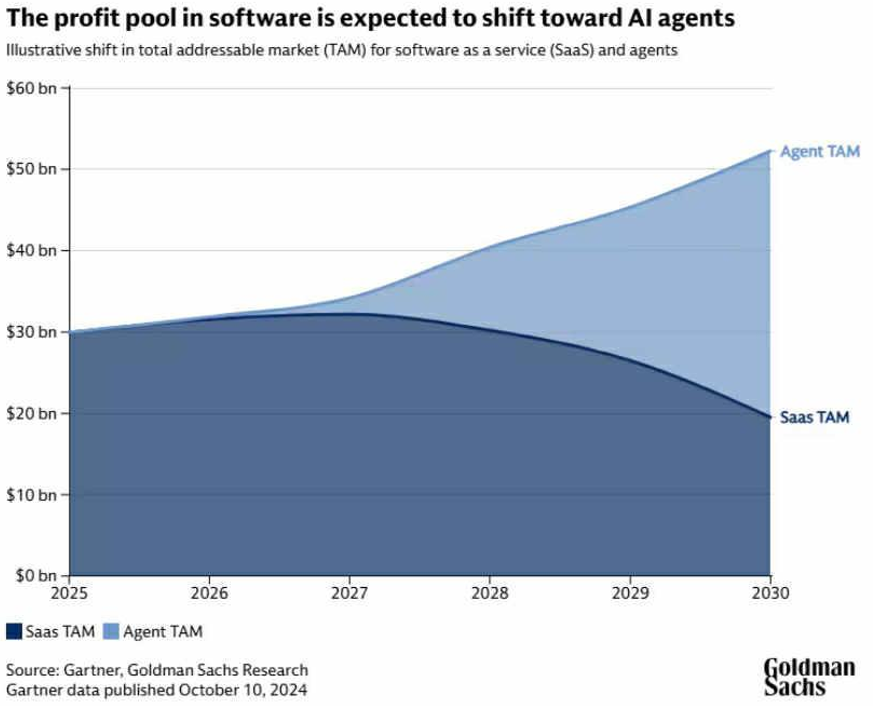

But the fundamental issue lies elsewhere: this massive CapEx is not neutral for the software economy. It does not simply add to what already exists; it calls into question the very value of many SaaS building blocks, transferring part of the value creation to AI agents capable of replacing, automating, or compressing functions that were previously billed as separate software services.

In other words, the risk for software is not having to directly finance data centers, but being cannibalized by AI itself: what was sold as a standalone solution becomes an integrated feature, sometimes virtually free, absorbed by the platforms that control the infrastructure and models.

This pressure on prices and margins automatically weakens SaaS business models, at a time when their multiples still incorporate assumptions of high growth and recurrence.

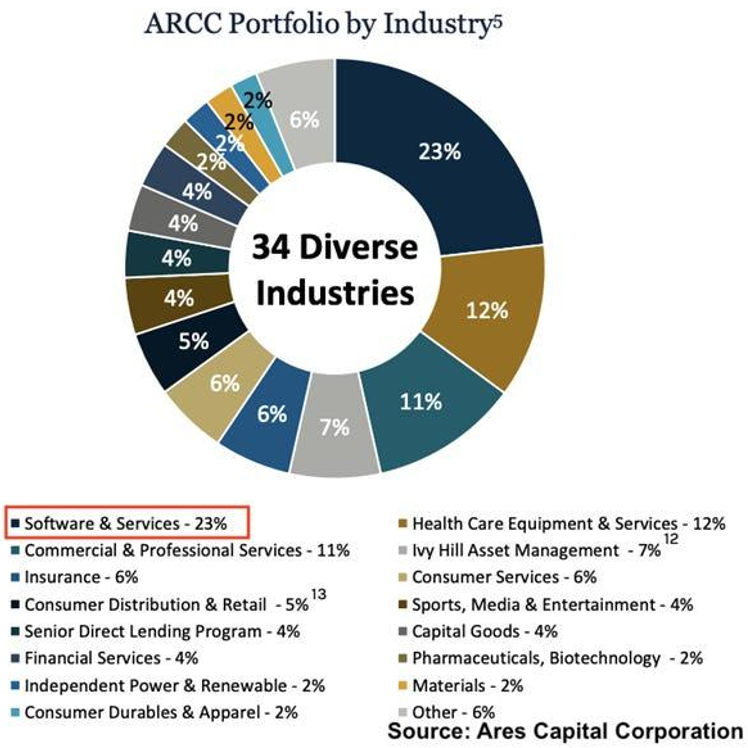

It is at this stage that the problem goes beyond equity to become a credit risk. A significant portion of private credit is exposed to software and “services,” often through end-industry classification.

This classification masks the economic reality: we think we are financing services, but in reality we are financing SaaS models threatened by AI substitution. In practice, actual exposure to software may be much higher than it appears, precisely because cannibalization does not occur by sector, but by function.

Behind loans to service, distribution, or healthcare companies, the real exposure is often technological. In other words, we think we are financing an industry, but in reality we are financing SaaS. When this dimension is taken into account, the actual exposure to software and the SaaS ecosystem can reach 50 to 55% of certain credit portfolios, without this being clearly apparent in traditional sector breakdowns.

The market is finally beginning to perceive this stress on the SaaS side, where recent corrections are no longer just market noise but a more profound questioning of models. Several players have seen sharp declines in recent days, including Salesforce, ServiceNow, Workday, and Atlassian, all penalized by fears of gradual cannibalization of their offerings by AI and pressure on multiples. This movement is beginning to spread to private credit, which until now had been perceived as protected. Major players such as Apollo Global Management, Ares Management, and Blackstone are seeing their exposure to software and technology services scrutinized much more closely. The key point is that this exposure is often masked by an “end-industry” reading: investors believe they are financing services, healthcare, or distribution, when in reality they are carrying a concentrated SaaS risk. The crack is no longer theoretical; it is beginning to appear simultaneously in equity and credit, a classic sign of stress spreading beyond its initial compartment.

The signs of stress are there. They are visible, sometimes intense, but as long as they do not directly affect indices and implied volatility, they are treated as irrelevant. However, market history is clear: it is precisely these phases of risk compartmentalization that precede the most brutal repricings.

In this context of widespread denial, the behavior of the gold price deserves special attention. Unlike silver, the yellow metal has not fallen in a disorderly fashion. Its relative resilience is not a sign of complacency, but rather of its monetary function. While the market still refuses to acknowledge systemic tensions, gold is not “panicking”: it is settling in. It gradually captures doubts about the sustainability of the regime—debt, CapEx, energy, credit—without requiring a visible shock to the indices. Historically, it is precisely in these phases of denial that gold begins to behave not as a tactical hedge, but as a store of value in the face of poor capital allocation. This is not an emergency signal, it is a fundamental signal.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.