Western investors are not rushing to buy gold, but are mainly focusing on passive investments.

This is one of the most striking paradoxes of the current cycle. In an environment marked by persistent inflation, geopolitical tensions, and record government debt, the historical reflex would have been to seek refuge primarily in gold. However, it is equity ETFs and passive strategies that are capturing most of the inflows. Not out of deep conviction, but out of habit.

For several months now, capital inflows into US equity ETFs have reached levels rarely seen before, to the point where they have become the main driver of the indices.

This trend is often interpreted as a vote of confidence in growth or in “American exceptionalism.” In reality, it mainly reflects a perceived lack of alternatives. Bonds no longer offer credible protection, cash is eroded by inflation, and non-US markets appear riskier or less liquid. Passive investing then becomes the default choice.

This shift has structural consequences. Passive flows do not analyze, prioritize risk, or discriminate on valuation. They buy what is rising, weighted by capitalization. The more flows come in, the more the same stocks are reinforced, the more the indices rise, which in turn attracts new capital. The market thus becomes self-referential, disconnected from fundamentals at the margins, but supported by the mechanics of flows.

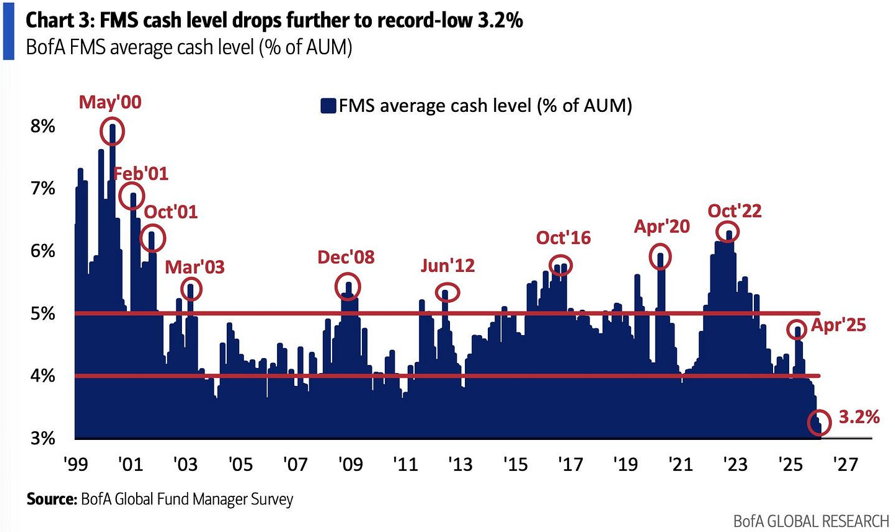

The latest Bank of America Global Fund Manager Survey sends a clear signal: the market is extremely optimistic. Global growth expectations are rebounding strongly, the average cash level has fallen to 3.2% of assets under management, a historic low, while protection against a decline in equities is at its lowest since 2018. In other words, managers are invested, confident, and under-hedged. At the same time, BofA's Bull & Bear Indicator is flashing at 9.4, a level historically associated with phases of advanced complacency. This type of configuration says nothing about the precise timing, but it greatly reduces the margin for error: when everyone is on the same side of the boat, the market becomes mechanically vulnerable to the slightest shock—macroeconomic, financial, or geopolitical. This is not a signal of an imminent crash, but a classic warning: marginal upside potential is shrinking, while risk asymmetry is deteriorating.

This is precisely what makes the situation fragile. Markets do not turn around when pessimism prevails, but when consensus becomes total. When everyone is already invested, the slightest surprise—macroeconomic, geopolitical, or financial—can trigger rapid adjustments, due to the lack of natural counterbalances. Volatility can then suddenly reemerge after having been suppressed for a long time.

In this context, the fact that gold is not yet capturing these flows is less a sign of weakness than an indicator of lag. History shows that real monetary assets are rarely bought first. They become central when confidence in financial constructs—indices, promises of liquidity, passive management—begins to crack. For now, Western investors favor simplicity and liquidity. But this choice speaks volumes about the state of the system: a market driven more by the structure of flows than by long-term conviction.

This highly bullish stance is not based on a broad and consistent improvement in fundamentals, but on a single promise: that of AI. The rise in indices is increasingly driven by an extremely small core of stocks directly associated with infrastructure, semiconductors, and software platforms related to artificial intelligence. The rest of the market is participating little, if at all. This concentration is the mechanical consequence of an environment where real growth is sluggish, margins are under pressure, and the cost of capital remains high: in the absence of credible macroeconomic drivers, capital is seeking refuge where the growth narrative appears most clear. The problem is not that this scenario is false, but that it has become the consensus view. When aggregate optimism, implicit leverage, and sector concentration simultaneously reach extremes, the market ceases to be driven by diffuse momentum and becomes dependent on the constant validation of a single narrative driver. It is precisely this type of configuration that makes corrections not only possible, but structurally unstable when they occur.

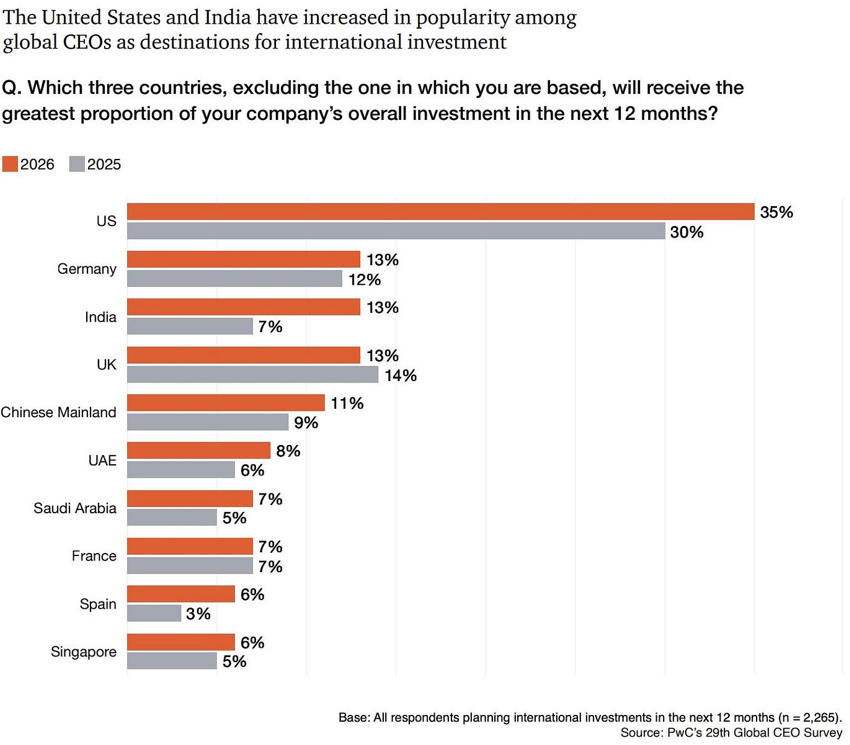

Massive investment in AI has become the central anchor of the US bull market frenzy and, by extension, one of the main sources of the current global financial imbalance. In the US, AI is the focus of growth narratives, capital flows, implied leverage, and risk tolerance, in a context where real growth outside of technology remains moderate and very unevenly distributed. This phenomenon creates a striking asymmetry: a handful of stocks capture most of the performance, while the rest of the global market—Europe, emerging markets, traditional cyclical sectors—lags behind. This concentration is not only stock market-related, it is also monetary and financial: it attracts global savings to US assets, strengthens the dollar, sucks up global liquidity, and forces other regions to cope with higher capital costs and more fragile growth. The paradox is that this dynamic is based on colossal investment in capex, energy, and infrastructure, the economic returns of which are still largely theoretical. As long as the promise of AI is believed, the system holds; but the more dominant this narrative becomes, the more global equilibrium depends on the continued validation of a single engine, located almost exclusively in the United States. It is precisely this asymmetrical dependence that makes the cycle both powerful... and inherently unstable.

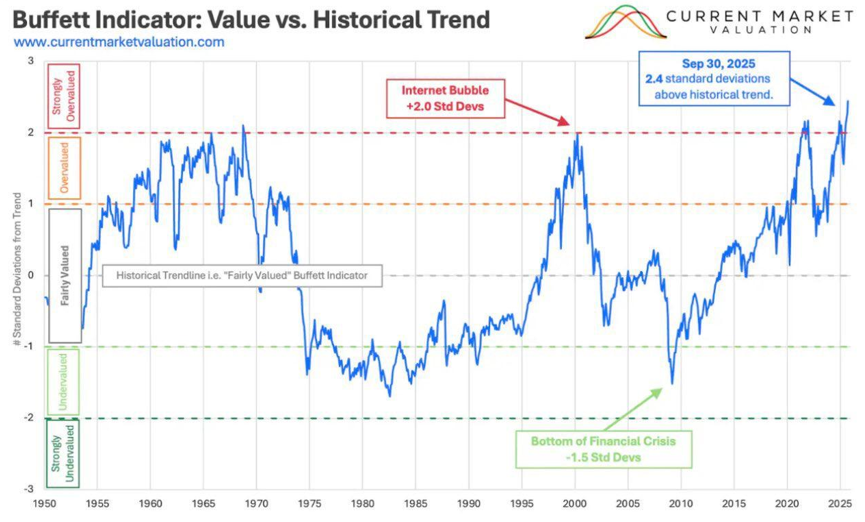

The AI frenzy has propelled the US market into historically extreme valuation territory, as clearly shown by the Buffett Indicator, which is now well above its long-term trend, at levels comparable to—or even higher than—those seen during the dot-com bubble.

The key point is not only that the market is expensive, but why it is expensive: this overvaluation is based on an exceptional concentration of growth expectations in a very limited number of AI-related stocks. In other words, the entire market is valued as if the promise of AI were not only going to materialize, but do so quickly, on a large scale, and without friction. Historically, such significant deviations from the trend have not signaled a precise timing of reversal, but they have almost always corresponded to phases where future returns were low and risk was asymmetric. In this context, the market is no longer driven by a generalized expansion of fundamentals, but by the anticipated capitalization of a still uncertain future, which makes the structure particularly sensitive to any disappointment in margins, capex, energy, or the actual pace of AI value creation.

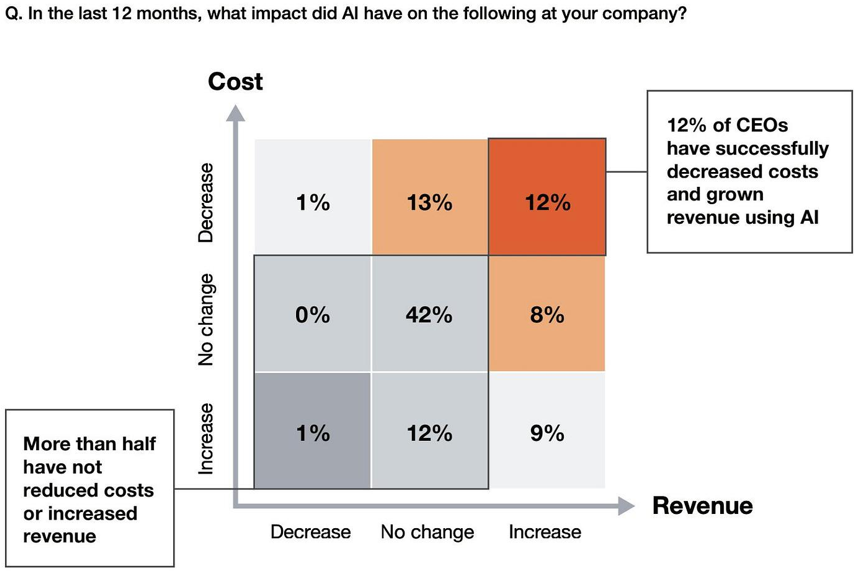

Added to this is a point that is often overlooked: AI is currently a huge consumer of capital, but not yet a visible producer of economic results. The figures speak for themselves: the vast majority of companies have seen neither a significant reduction in costs nor a tangible increase in revenues linked to AI.

In other words, the market capitalizes on future promises even though, in the present, AI mainly translates into massive capital expenditures, rising energy costs, heavy infrastructure, and increased operational complexity. The parallel with commodities is illuminating: a mine also requires high, often increasing, capital expenditure, but at the end of the process, it produces a tangible, measurable, monetizable asset with clear physical and financial flows. AI, on the other hand, remains largely an option on future gains, the timing, scale, and diffusion of which remain uncertain. The risk is therefore not so much that AI will fail, but that the market will anticipate too quickly, too strongly, and too concentratedly benefits that are not yet visible in the accounts. In this context, the fragility stems from the gap between the amount of capital committed and the modest returns seen at this stage—a gap that, if it persists, makes the narrative much more vulnerable to the slightest slowdown, disappointment, or financial constraint.

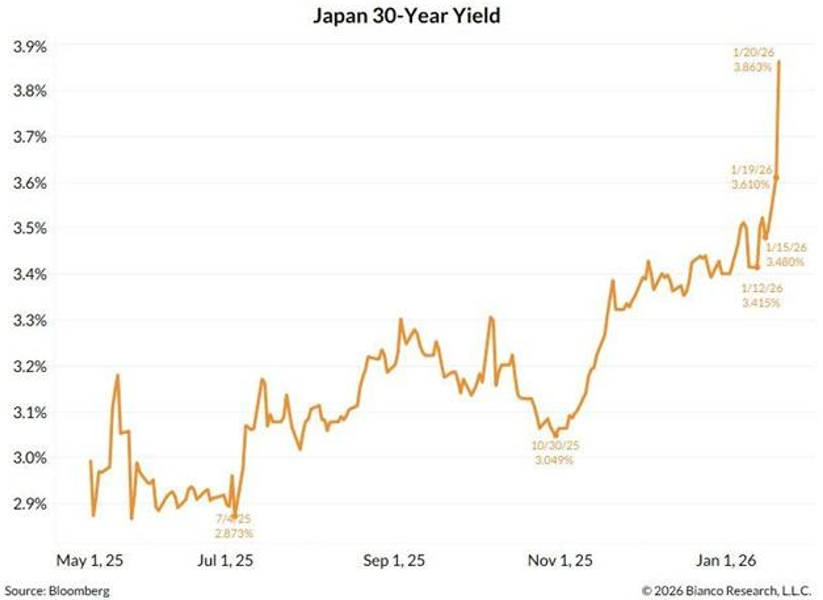

Artificially propping up the market through defensive mechanisms such as short selling, even as fundamentals weaken, creates particularly fertile ground for gold. When the apparent stability of indices is based less on real economic improvement than on the mechanical suppression of volatility, the system becomes dependent on flawless execution and constant risk control. At the same time, the rapid rise in Japanese interest rates, long considered the anchor of global stability, is introducing a source of structural stress on interest rate markets, carry trade, and global liquidity.

This combination—high valuations, artificial suppression of volatility, cracks in the Japanese pillar, and the return of tariff tensions—creates an environment where confidence in financial assets is maintained, but under increasing strain. The hardening of trade rhetoric and the reactivation of tariff mechanisms introduce an additional layer of uncertainty on value chains, margins, and imported inflation, at a time when markets are already hypersensitive to the slightest liquidity shock. Historically, this type of configuration does not trigger an immediate crisis, but gradually redirects flows toward gold, not as a panic asset, but as systemic insurance against a fragile balance that has become overly dependent on artificial mechanisms and defensive monetary policies. The gold price is setting new records in this context, breaking through the $4,750 mark for the first time, while silver is approaching $100, driven by persistent physical tensions and premiums in Shanghai that continue to soar.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.