On November 1, Christine Lagarde took over from Mario Draghi at the ECB, i.e. where the destruction of our currency is being implemented. What kind of policy can we expect from her, and what conclusions can we draw from it in terms of personal finances?

Is the president of the ECB a decision-maker or an implementer?

Contrary to a widespread media legend, Mario Draghi did not save the euro. All he did was implement a monetary policy in line with the political choice made in July 2012 by the heads of state or government. The latter had decided by mutual agreement that Greece should remain in the eurozone, which was therefore destined to last and not to explode.

The "whatever it takes" statement made by the president of the ECB on July 26, 2012 is therefore merely the translation into the mouth of a bureaucrat of a decision taken upstream by politicians. Mario Draghi is therefore not the "saviour" of the eurozone. At most, he is the one who decided how he was going to take his respite. The independence of the ECB from political power being all that is more theoretical, the post of president of the ECB thus resembles more that of a workshop manager than that of a CEO.

If, therefore, what goes on at the ECB is to be monitored very closely, Frankfurt should be seen as a production centre rather than a decision-making location.

With Christine Lagarde, the political authorities have decided to take the plunge

Moreover, it is the heads of state or government who appoint the president of the ECB, its vice-president and the other members of the executive board - Parliament has only to give its opinion on this matter.

Since July 2, we have therefore known that the ECB will be led for the next eight years not by a former president of the Central National Bank - as has always been the case until now - but by a personality who shines above all for her political ability, and not for her technical expertise in the field of economics and finance.

However, Christine Lagarde is not without convictions. She differs from Jens Weidmann, for example, in that she is steeped in Keynesian ideas, as her tenure as head of the IMF shows. In Washington, she will remain as the person who steered the institution towards supporting very low interest rate policies, while at the same time being alarmed by their consequences in terms of all-out debt, in the greatest tradition of the pyromaniac fireman.

In short, she is the ideal candidate to pursue a policy of monetary flight to the top even further.

Furthermore, it is seriously doubtful whether there is yet another choice for the eurozone.

Will the ECB ever raise rates?

As Natixis explained almost a year ago, the interest rate policy in the eurozone (as in Japan) seems to be a foregone conclusion.

On March 15, 2019, Patrick Artus warned:

"A long period of low interest rates is:

- irreversible, due to the effect of an increase in interest rates on the value of bond portfolios and on borrower solvency;

- dangerous, due to the appearance of zombie companies and dominant positions and the weakening of banks.

Central Banks have therefore fabricated an irreversible and dangerous situation”.

Note that here, Natixis does not even mention the consequences of a rise in interest rates on the public finances of the member states in the zone. However, the bank has taken care of this in a note published on December 11.

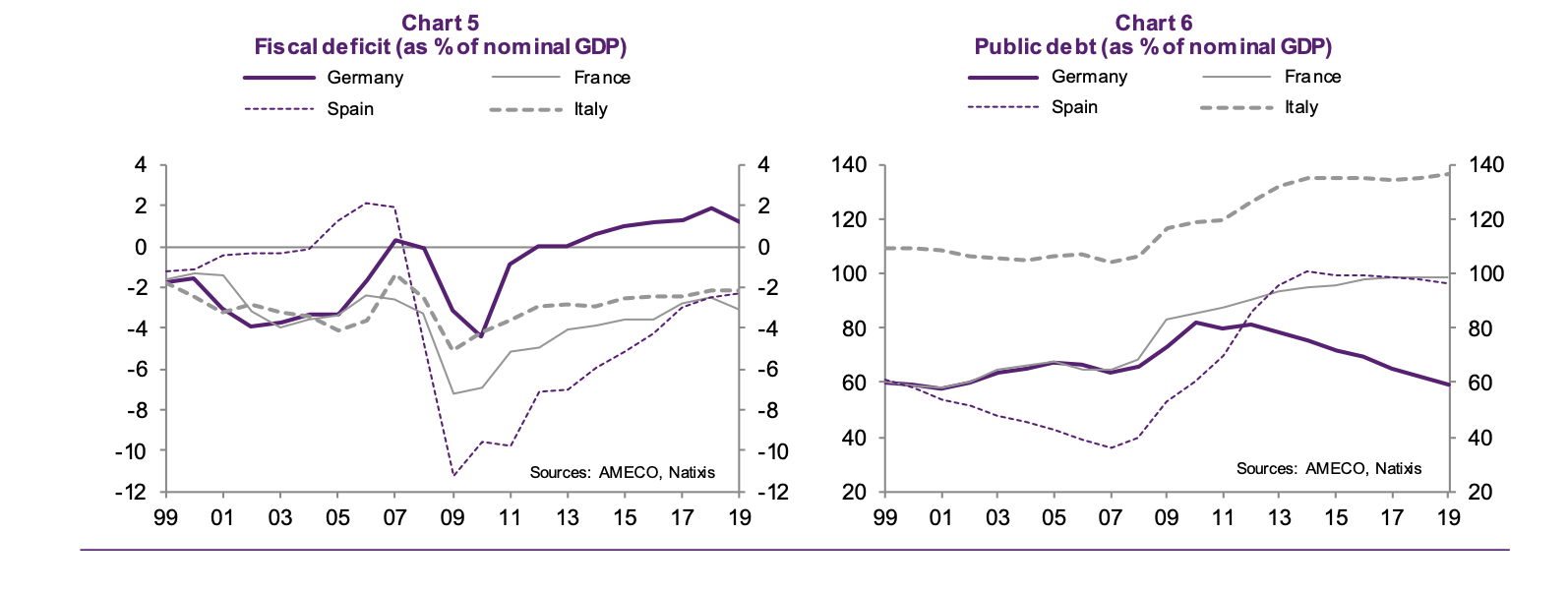

This shows that a normalisation of the ECB's monetary policy would have dramatic consequences for certain states since:

"...in a ‘normal’ situation, 10-year interest rates would be:

- 2.2% in Germany;

- 3.8% in France;

- 3.8% in Spain;

- 5.1% in Italy, [which] would pose a fiscal solvency problem ".

Indeed, as Patrick Artus points out, "the apparent interest rate on the debt would increase by:

- 80 bp in Germany

- 230 bp in France

- 150 bp in Spain

- 250 bp in Italy

Debt interest payments would increase by:

- 0.5 pp of GDP in Germany

- 2.3 pp of GDP in France

- 1.5 pp of GDP in Spain

- 3.4 pp of GDP in Italy".

In the end, you will not be surprised to read that "the fiscal deficit (Chart 5) [would probably be at] an unsustainable level given the public debt ratio (Chart 6) in France, Spain and Italy".

In other words, low rates have a bright future ahead of them.

All this for 1.4% growth in the eurozone in 2020... and 1.1% growth in France

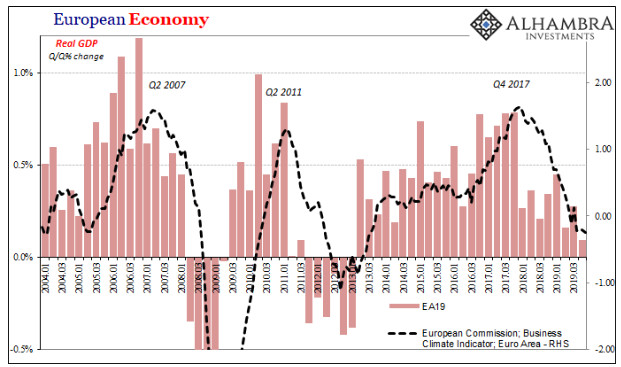

And that is not all, since the results of the ECB's policy are bad. As Patrick Artus wrote last May, "After five years of highly expansionary monetary policy in the eurozone, the German ten-year interest rate became zero or negative in the spring of 2019. This shows that five years of highly expansionary monetary policy have failed to :

- lift the eurozone’s potential growth;

- lift expected inflation in the eurozone;

- prevent the current cyclical downturn in the eurozone.

All this shows the relative effectiveness of the highly expansionary monetary policies.

Moreover, the return of zero long-term interest rates is going to weaken banks and further endanger future growth in the eurozone".

This observation is still very relevant as the European Commission has just announced its growth forecasts for 2020. On February 13, Brussels was forecasting an average of 1.4% for 2020, the same level of growth as England, according to the IMF. Emmanuel Macron will therefore have a hard time showing off in front of Boris Johnson since only our German and Italian neighbours will in principle do worse than us:

If we take a step back, we can see along with Bruno Bertez that, "[t]he economy is in tatters, look at this long-term evolution, it is sinister. But the short- and medium-term trend is no more encouraging".

In short, contrary to what "the ECB regularly tells us":

Christine Lagarde's hands are tied

In the end, not only is the policy pursued by the ECB dangerous, but it has become irreversible and, what is worse, it is not working. The patient is on life support and cannot withstand even the slightest power outage.

Christine Lagarde will therefore also do "whatever it takes" to keep the eurozone alive, until the day when the heads of state and government informally ask her to disconnect the patient, after a political decision has been taken.

It is therefore not surprising that "gold [is] climbing to new heights against the euro as if it were a vulgar emerging market currency", to quote Bruno Bertez.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.