Many news agencies have relayed the now viral video of Kenyan President William Ruto's speech at the Summit for a New Global Financial Deal organized by French President Emmanuel Macron.

SEE IT: #Kenya President @WilliamsRuto lectures French President @EmmanuelMacron, IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva (@KGeorgieva), and @JoeBiden's newly appointed @WorldBank President Ajay Banga. Tells them they are not listening. We do not want anything for free. We no… pic.twitter.com/MooPPMxqEn

— Simon Ateba (@simonateba) June 25, 2023

This intervention caused quite a stir on African social networks, as it reflects a new form of language, which we will attempt to analyze.

Firstly, the tone of this intervention is completely new. William Ruto apostrophized the French president and called him by his first name, Emmanuel, thus marking his desire to position himself as an equal with him. Such familiarity is exceedingly rare at a public meeting with an African head of state.

Kenya is in a very complicated fiscal situation, with a national public debt of $67 billion. It is the seventh most indebted country in Africa, after Egypt ($352 billion), South Africa ($268.8 billion), Nigeria ($99.9 billion), Morocco ($84.1 billion), Algeria ($83 billion) and Angola ($76 billion).

"In Kenya, we pay around 10 billion dollars every year to honor our debt. If we were to use it instead for the country's development, it would be an immediate redirection of immense resources, and it would have an enormous impact on the energy transition, health, electrification, etc. To achieve this, all we need to do is convert the money we were supposed to pay to the World Bank, the IMF and all the other lenders into a 50-year loan facility with a 20-year grace period," explains William Ruto.

Refinancing the country's debt is extremely difficult, and access to new credit is proving increasingly complicated. The country is no longer able to access development programs set up by Western donors.

In such a situation, the Kenyan president should have adopted a much more reserved attitude. Negotiations on African debt with the IMF are traditionally conducted in a very discreet and measured manner. What could have prompted William Ruto to change his stance towards the IMF President and the French President?

"Not the IMF, not the World Bank. We want another organization where we have as much say as you do."

William Ruto calls for a different form of global organization for debt issuance.

Why is this different from the demands made by Pan Africanism 20 years ago?

Since then, the level of indebtedness of Western countries has evolved. 20 years ago, Western countries and the IMF, the organization they set up to manage the financing of developing countries, could back their policies with a certain credibility. Things were fairly straightforward: on the one hand, the rich countries were creditors, and on the other, the poor countries were debtors.

Today, the level of indebtedness of Western countries has changed the way poor countries view the debt problem.

Pan Africanism in 2023 notes this difference in treatment of public debt. In calling for a change in the rules set by the IMF, the President of Kenya points to this injustice. Wealthy countries have better access to credit. For over 10 years, the monetary policy of central banks has provided access to free money, while African countries have had to make do with "preferential rates" granted by the IMF. Africa was too far from the money printing press to benefit from the enrichment seen over the last decade.

The health crisis in particular changed the situation. Western countries faced a shock that they were only able to overcome thanks to massive public indebtedness.

But it wasn't international bodies like the IMF that intervened. The dollar's status as an international reserve currency enables the United States to absorb this type of shock. This is not the case for African countries, which have to borrow. African countries have only the IMF to negotiate their debt, whereas Western central banks have a number of financial tools (swaps, special financing windows) that enable them to obtain better credit terms.

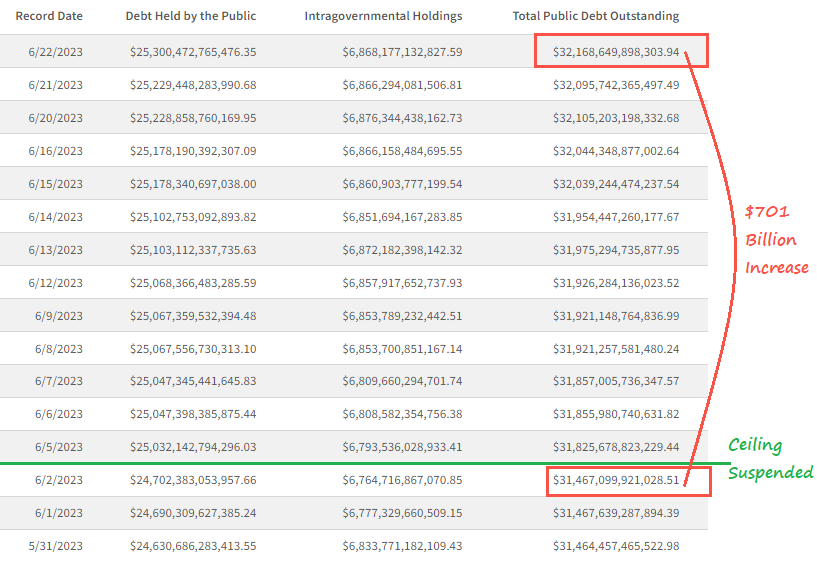

Since the beginning of June, the United States has borrowed over $700 billion to keep its government running and meet its debt repayments:

That's $54 billion in debt created every day!

In other words, every day, the American government can freely take on $162 in debt per capita, while the average African earns $5 a day ... and Western countries continue to force indebted African countries to find refinancing solutions from the IMF, an organization financed by countries that control the money printing press!

As long as the fiscal situation of Western countries was respectable and respected, IMF constraints could be understood and accepted. Today, they are much less so. Why don't Western countries, like the Africans, have to renegotiate their abysmal IMF debt? Why is it more difficult and costly for African countries to finance their debt, while Western countries are far from being good performers when it comes to public debt?

France is far from exemplary in this area.

In an interview published by El Pais, Germany's Minister of the Economy points out that France has never implemented the reforms needed since 1980 to solve its debt problem. This attitude is unacceptable in the context of monetary union. In other words, France goes into debt knowing full well that it will always have a solution for financing itself on the markets, without worrying about balancing its books. Germany criticizes France for not behaving like an adult when it comes to its debt.

And it is in this context that we observe William Ruto's familiarity with Emmanuel Macron. The French president is no longer in a position to position himself as a European "adult" vis-à-vis his African "child".

How can we maintain a debt financing system that is now run by poor performers? How can we impose such strict conditions on poor countries when Western countries themselves choose not to repay their debts and issue new ones when faced with an economic shock?

Peter Schiff has given a very specific explanation of this debt-rolling process in Western countries, which he likens to a Ponzi pyramid scheme.

In an interview, Peter Schiff argues that the recent debt ceiling debate should have shaken confidence in the dollar. He adds that the U.S. Treasury depends on new borrowing to pay off its existing debt, which is consistent with the definition of a Ponzi scheme. In his view, the U.S. government's scam cannot stand.

Peter Schiff points out that raising the debt ceiling is based on the idea that the U.S. always pays its bills. But in reality, the opposite is true. The reason the US government has to raise the debt ceiling is because it never pays its bills!

It's only logical, then, to see a change in the outlook of developing countries. And it's easy to see why the BRICS are making inroads with these countries.

Jim Rickards predicts that the BRICS+ countries will announce the creation of a new currency at the annual summit of their leaders, to be held August 22-24, 2023.

BRICS gold standard: the biggest currency shock in 52 years (@JamesGRickards)

— GoldBroker (@Goldbroker_com) June 27, 2023

▶ https://t.co/s2pyarfyIX@DailyReckoning #gold #BRICS #China #Russia #dedollarization pic.twitter.com/Hl1a1g7MKF

This new currency will form the basis of an international trading system that will dispense with the dollar and all its associated systems (SWIFT system, international organizations such as the IMF, interbank organizations such as BIS, etc.).

Jim Rickards announced that this currency would be backed by gold. Its use would significantly enhance the value of natural resources in emerging countries.

It could also create more competitive financing solutions for these emerging countries.

The promise of a new exchange system, offering an alternative to the classic dollar/IMF system, is probably one of the reasons why African countries like Kenya have changed their tone towards the IMF and Western countries.

This explains the recent purchases of gold by these countries' central banks: physical gold is the only tool for making a successful transition to this new de-dollarized system.

On December 18, 1912, the most influential financier and banker of his time, John Pierpont Morgan, was called to testify before the U.S. Congress.

Except from deposition with Samuel Untermeyer, Chief Counsel of the Pujo Subcommittee of the House Committee on Banking and Currency, established at the time to investigate the influence of Wall Street bankers and financiers on money and credit in the United States:

Mr Untermeyer: I want to ask you a few questions bearing on the subject that you have touched upon this morning, as to the control of money. The control of credit involves a control of money, does it not?

Mr Morgan: A control of credit? No.

Mr Untermyer: But the basis of banking is credit, is it not?

Mr Morgan: Not always. That [credit] is an evidence of banking, but it [credit] is not the money itself. Money is gold, and nothing else.

At a time when global debt represents three times world GDP, and in the face of unfair differences in access to debt, emerging countries suddenly seem to realize the difference between debt and currency.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.