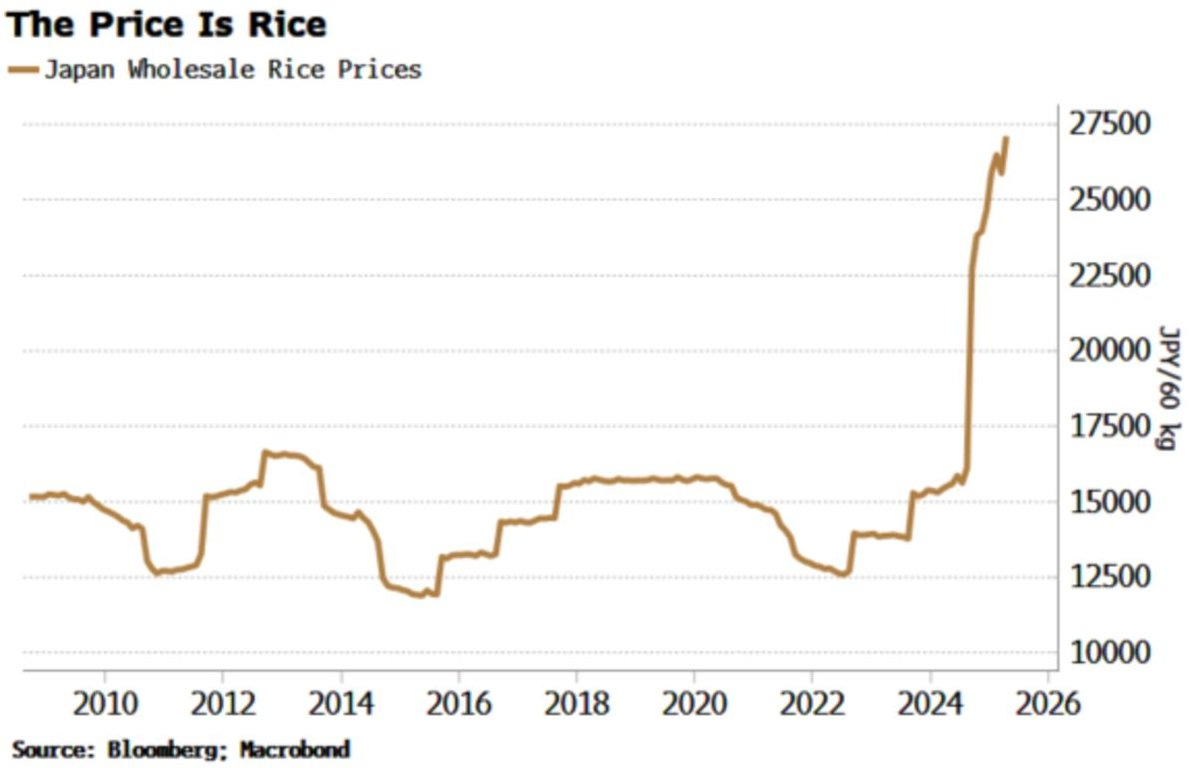

Japan is currently undergoing a critical period that is shaking the apparent stability of its economy. Although underlying inflation remains contained, the soaring price of rice - an emblematic and central commodity in the Japanese household consumption basket - has shaken perceptions of the cost of living. In just a few months, wholesale rice prices have almost doubled, topping 27,000 yen for 60 kg, as illustrated by the Bloomberg graph:

This sudden increase, both perceptible and tangible in everyday life, quickly sent shockwaves through the political arena. The government's initial response was to authorize the release of 200,000 tons of rice from strategic reserves, before abruptly suspending sales in the face of distributors' unexpected enthusiasm. This initiative, aimed at easing inflationary pressures in the run-up to the summer elections, reveals a much deeper tension: Japan is sacrificing its food security reserves in an attempt to contain a crisis of perception, symptomatic of a structural imbalance.

But the real threat is emerging on a completely different front: the Japanese bond market. Since April, yields on very long-term securities - notably 40-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs) - have jumped by almost 100 basis points:

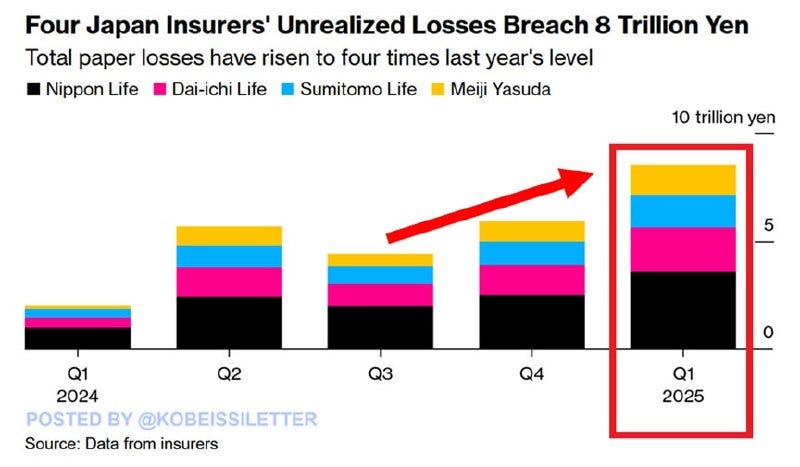

Worse still, the inversion of the curve between 35- and 40-year maturities - where the former now offers a higher yield than the latter - signals a profound malfunction. This kind of anomaly only emerges in extremely stressed markets, where liquidity disappears and valuation benchmarks collapse. Japanese institutional investors are already recording substantial latent losses - estimated at over 3.6 trillion yen, according to their March 2025 reports:

In the first quarter of 2025, four of Japan's leading life insurance companies posted colossal unrealized losses, exceeding $60 billion in total. Nippon Life - the industry leader - alone accounted for $25 billion in unrealized losses, a 260% year-on-year increase. This figure reflects the collapse in the valuation of bond portfolios, a direct consequence of the sharp rise in Japanese government bond (JGB) yields, particularly on long maturities.

These losses have not yet been recognized in net income, as they concern securities held to maturity or classified as long-term investments. However, they considerably weaken the apparent solidity of the balance sheets of these insurers, whose financial health is based on rate stability, which is now compromised. If rates remain persistently high, or if a deterioration in the market forces these players to liquidate their securities, the latent losses could materialize, jeopardizing the equilibrium of the entire Japanese insurance sector.

This phenomenon raises a broader concern: the sustainability of the Japanese model, based on decades of ultra-low interest rates. Life insurance companies, like pension funds, have invested massively in fixed-income securities, particularly very long-term JGBs. The current market downturn calls into question not only the valuation of their portfolios, but also their ability to continue guaranteeing stable returns to their policyholders, against a backdrop of an accelerating ageing population.

The Bank of Japan, which holds more than half of the entire domestic bond market, can no longer hide the truth indefinitely. By reducing its support, it is revealing the naked reality: Japanese bonds are no longer worth what they were thought to be. Losses are piling up, confidence is eroding, and the market is losing its footing.

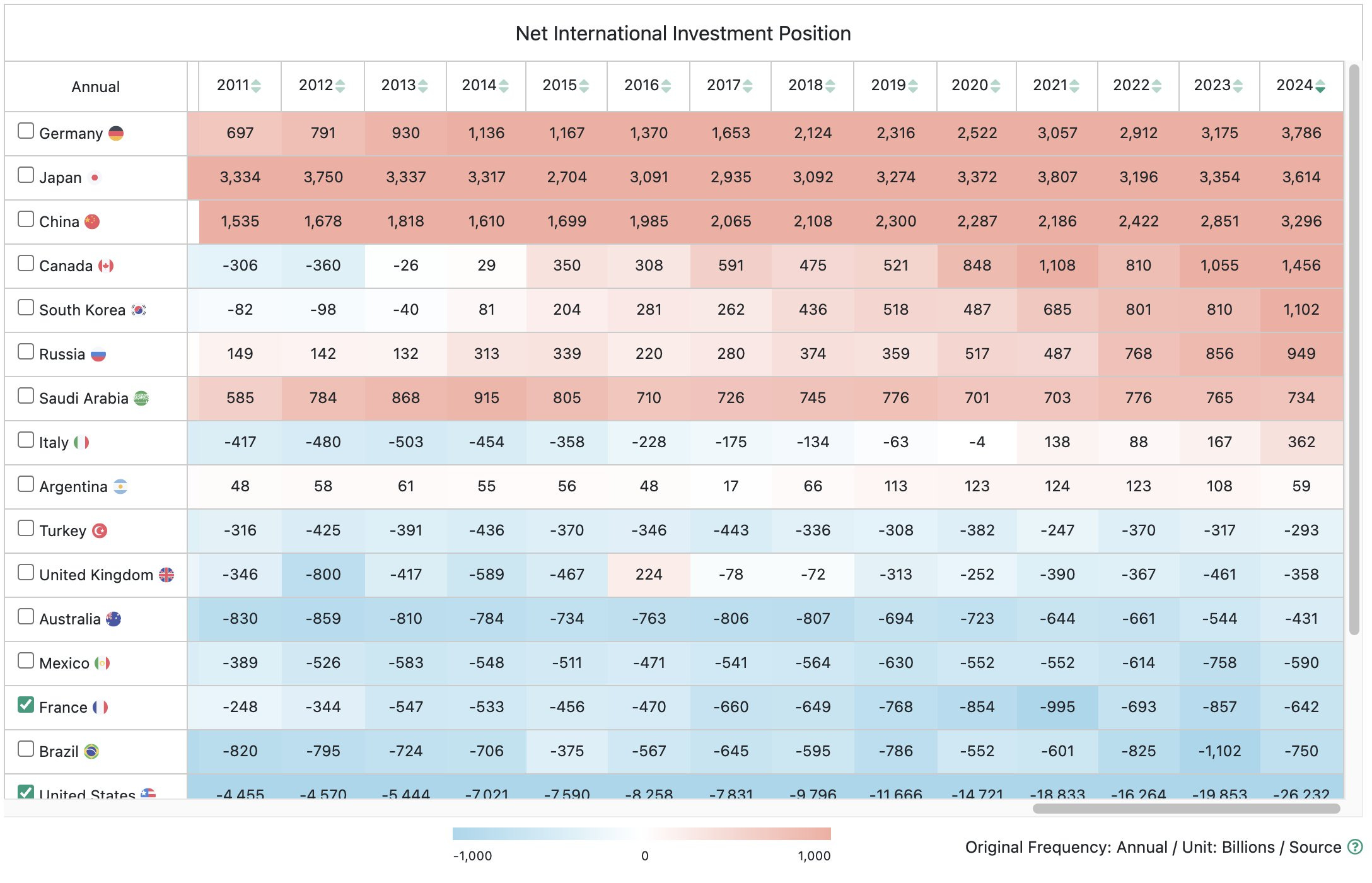

This shock comes at the worst possible time. Once perceived as the world's most reliable sovereign issuer and the world's leading net creditor, Japan has just lost that status. It is now overtaken by Germany, as shown in the net international investment position table:

The yen's depreciation has accelerated this downgrading, but it is above all the growing need to repatriate capital - to manage the domestic crisis - that is the main cause. The global implications are considerable. Japanese institutions hold over $4 trillion in foreign assets, a significant proportion of which is in US and European bonds. If they are forced to liquidate these positions to strengthen their domestic balance sheets, Western rates will rise further, triggering a new shockwave on markets already weakened by US deficits. This week's poor auction of 20-year US bonds may well be the first sign of things to come.

The mechanics of the yen carry trade, a discreet but powerful driving force behind the rise in global assets over the past two decades, are also breaking down. As JGB yields become more attractive, Japanese investors are repatriating their funds, unwinding positions that had previously supported US equities, European bonds and emerging markets.

Earlier this week, Japan's Ministry of Finance (MoF) quietly intervened in the bond market panic following a surge in long-term rates. It sent a questionnaire to the main market players on JGB issuance volumes, hinting at a possible reduction in supply to calm volatility. This initiative immediately sent the 20-year yield tumbling by more than 20 basis points, reflecting an attempt to regain control of the market through technical adjustments, without a formal monetary policy announcement.

The USD/JPY chart, which shows erratic movements following interventions by the Ministry of Finance, testifies to the growing feverishness:

A drop in the USD/JPY pair below 140 would indicate a massive flow of capital back to Japan - a potential signal of systemic stress. There is also abnormal activity in S&P 500 futures during Asian hours, suggesting that Japanese institutions are actively hedging or selling international assets in the middle of the night.

The financial world may be on the verge of a regime change. Financial repression, thought to have been relegated to the past, is making a discreet comeback through the Japanese door. The Tokyo authorities are already trying to manipulate the yield curve by adjusting the supply of debt, hoping to stem the panic without triggering a crash. But markets move faster than political decisions, and precedents - notably that of August 2024 - show that when Japanese institutions start to sell off, the repercussions are immediate and spread worldwide.

I wrote about this panic in my bulletin from last August.

Up until now, the Japanese bond crisis had been barely contained. The Bank of Japan's intervention in August 2024, combined with carefully-calibrated communication from the Ministry of Finance, had created an artificial calm on the markets and bought time. This reprieve, lasting only a few months, gave the illusion of a return to control of the situation. In reality, it was only a reprieve, not an actual solution.

This week's discreet intervention - via a simple questionnaire sent by the MoF to primary market participants - aims to regulate the supply of JGBs, and thus momentarily relieve the pressure on long rates. In response, 20-year yields retreated by over 20 basis points in the space of a few hours. It's a tactical victory, to be sure, but it doesn't change the fundamentals: indebtedness remains massive, structural demand for bonds is eroding, and the balance sheets of Japanese insurers and banks are increasingly fragile. In other words, we've probably gained a few weeks' stability, but no more.

In major bond crises, the breaking mechanism is often the same: the system cracks slowly at first, and then suddenly everything falls apart. As long as losses remain latent, as long as no one sells, everything seems under control. But at a certain point - when investors start selling to protect themselves, or when losses become too visible to ignore - the movement gets out of control. Prices fall, rates explode, losses materialize suddenly, and the panic instinct takes over from analysis.

This is the inflection point that Tokyo now fears. Every intervention becomes a desperate attempt to postpone the inevitable. But as in all crises of confidence, the longer the shock is delayed, the greater its final impact.

At a time when bond markets are losing their bearings and central banks themselves appear to be in a fragile position, physical gold is once again an anchor of stability and accounting truth. Unlike financial assets, which are based on promises (of payment, repayment or return), physical gold is not the counterparty to any debt, government commitment or monetary policy. It needs no trusted third party to exist or maintain its intrinsic value.

This is precisely what makes it the only asset that can insure against a systemic bond shock. Because, in a deep bond crisis, it's not just yields that adjust: it's the whole edifice of government debt that cracks, with knock-on consequences for currencies, bank reserves, pension funds and confidence in governments themselves. When holders of government bonds (insurers, central banks, pension funds) realize that these assets are no longer risk-free, the reflex is to look for a universal, liquid and elusive store of value: that's when gold comes into the picture.

But only direct ownership of physical gold - not paper, not mortgaged, not stored with a risky intermediary - offers this ultimate insurance. Paper gold (ETFs, contracts, certificates) can be suspended, taxed or even disconnected from its real underlying in times of stress. Physical gold, on the other hand, is not dependent on markets, banks or settlement platforms. At both individual and institutional levels, it is the only asset that is totally outside the system, allowing it to escape the reach of policies of financial repression, capital control or indirect confiscation through inflation.

In a world where the major monetary powers are all simultaneously out of balance - the United States with its deficits and its weakened dollar, Japan with its failing bonds, Europe with its political instability - the possession of physical gold is akin to an insurance policy against the improbable that has become possible: a collapse in confidence in sovereign debt.

Beyond the current crisis, it is a model that is faltering. Japan can no longer play its traditional role as the ultimate lender, the silent stabilizer of world markets. The reflux of Japanese savings is forcing the system to reinvent itself. So what's happening in Japan is not just a crisis of rates or exchange rates, it's a signal: the rules of global credit are being rewritten, and those who anticipate will be one step ahead.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.