Investors are always looking to history for guidance by attempting to find the most economically comparable period to the present. Two timeframes are the most conspicuous, the '40s and the '70s.

However, today’s environment is significantly more extreme.

In resemblance to today, the economy of the 1940s had high government debt and large fiscal deficits relative to GDP along with repressive Fed interest rate policies.

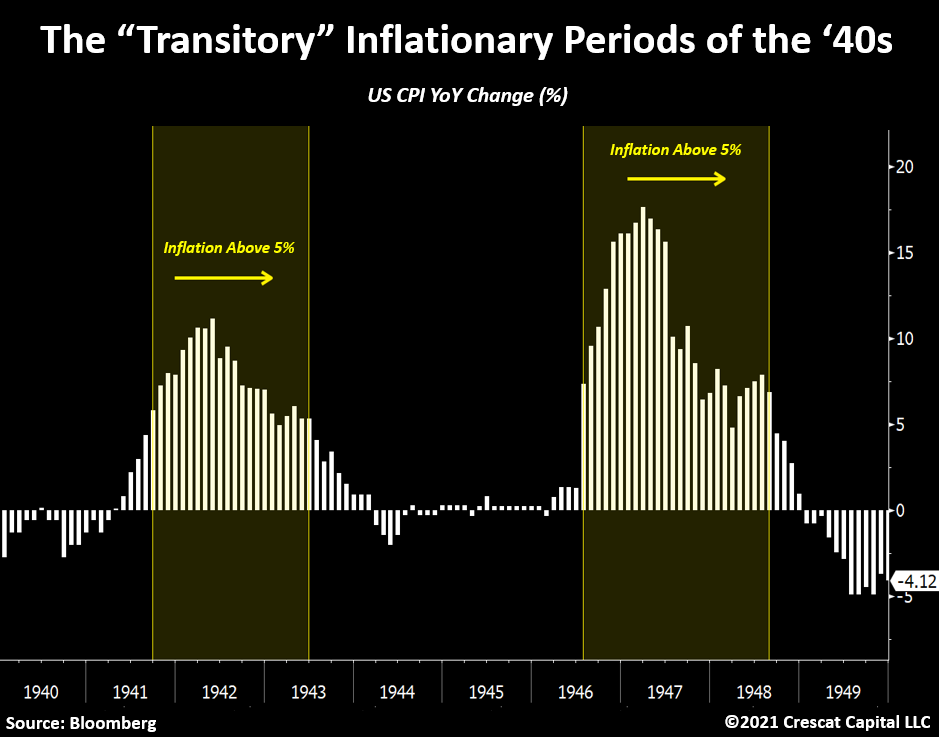

It was a decade that included two sharp waves of increasing inflation in the Consumer Price Index, the first during World War II and the second right after it.

Monthly CPI rose to a short-term peak of 13.2% on a year-over-year basis in 1942, and while it fell back down to 0% in 1944, it then spiked again to a higher peak of 19.7% in 1947, the highest year-over-year CPI increase of the last century.

Some macro investors today are citing the 1940s to validate the Fed’s hypothesis that the recent rise in consumer prices will prove to be transitory.

However, note that during each of those inflationary spikes, CPI stayed above a 5% YoY rate every month for over two years. If the past is prologue, this period supports the idea of inflation getting much worse before it gets better today.

Unlike the 1940s, when the US dollar was still pegged to gold, in the 1970s we had the abandonment of the gold standard which marked the onset of five decades of limited financial and monetary discipline ever escalating to the historic macro imbalances we have today.

Such a shift in the monetary system was just as significant as today’s unlimited QE policies.

The consequence of the macro setup during that era was that inflation rose in three waves from the late 1960s through the 1970s to reach a peak of 14.7% in 1980. Those waves were steadier and more persistent than the inflationary waves of the 1940s, we think due to the long-term, trending dynamic of the wage-price spiral that was at work.

Interestingly, both of those regimes, along with today’s, share one thing in common: negative real interest rates.

The 1940s was the most financially repressive environment yet in that respect. The Fed at least allowed interest rates to rise in the 1970s while inflation rose faster.

From a market perspective, there was one important lesson from both periods: At times when investable assets yield less than inflation, owning tangible assets becomes imperative. Commodities were far-and-away the best performing asset class in both of those decades.

The Fed today is favoring the 1940s’ style of financial repression. It is “not even thinking about thinking about” raising interest rates anytime soon. The definition of financial repression is deliberate government and Fed policies that result in savers earning returns below the rate of inflation. The purpose of it is to inflate away excessive debt burdens, especially at the government level.

As a result, we are experiencing the loosest monetary policy of all time today.

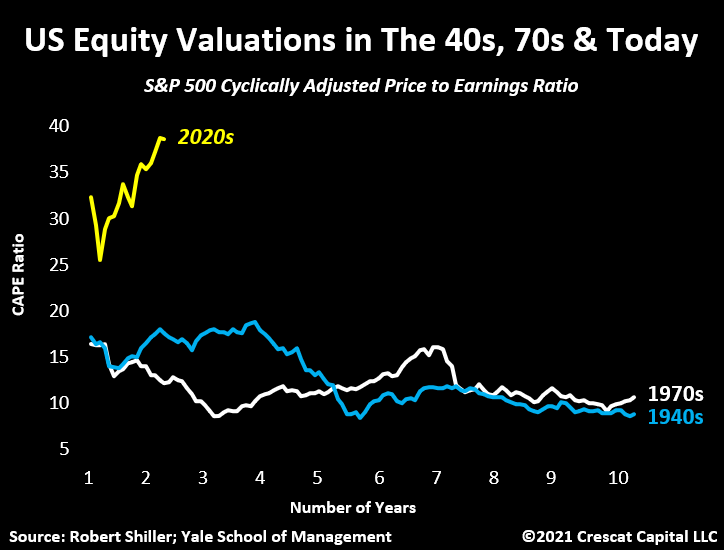

Meanwhile, the valuation of the stock market, which is highly dependent on the suppression of the cost of capital, far exceeds the periods of the 1940s and 1970s.

Using Robert Shiller’s cyclically adjusted price to earnings ratio as a gauge, we are at 38.3 times today. That is more than double what we saw during the most overvalued levels reached during those two decades.

Even more significantly, the market cap of US stocks relative to nominal GDP is by far greater than any other time in history. The levels of overall debt are also materially higher.

Total debt, including private and public, as a percentage of GDP is almost double the size of the 1940s and 1970s.

Now, let us get back to the 1940s case study.

While the Fed was able to keep short and long-term interest rates subdued at that time, US households played a major role in accomplishing that.

As a form of patriotism, Americans purchased large amounts of US government bonds to finance military operations and production.

To put this into perspective, World War II cost the US close to $300 billion. Households funded almost $185 billion of that amount. This level of participation by US investors to fund large government deficits is completely absent today.

While we continue to see record levels of Treasury issuances in the market, the increasing dependence on the Fed and banks to continue funding extreme deficits has never been greater.

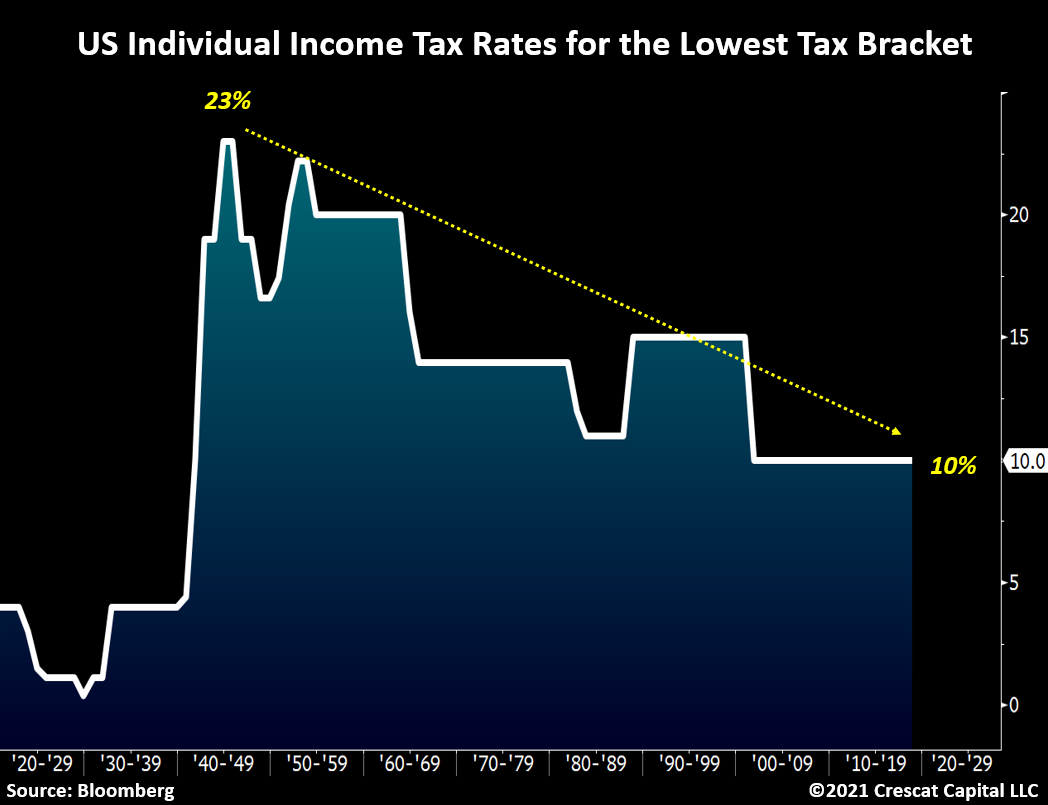

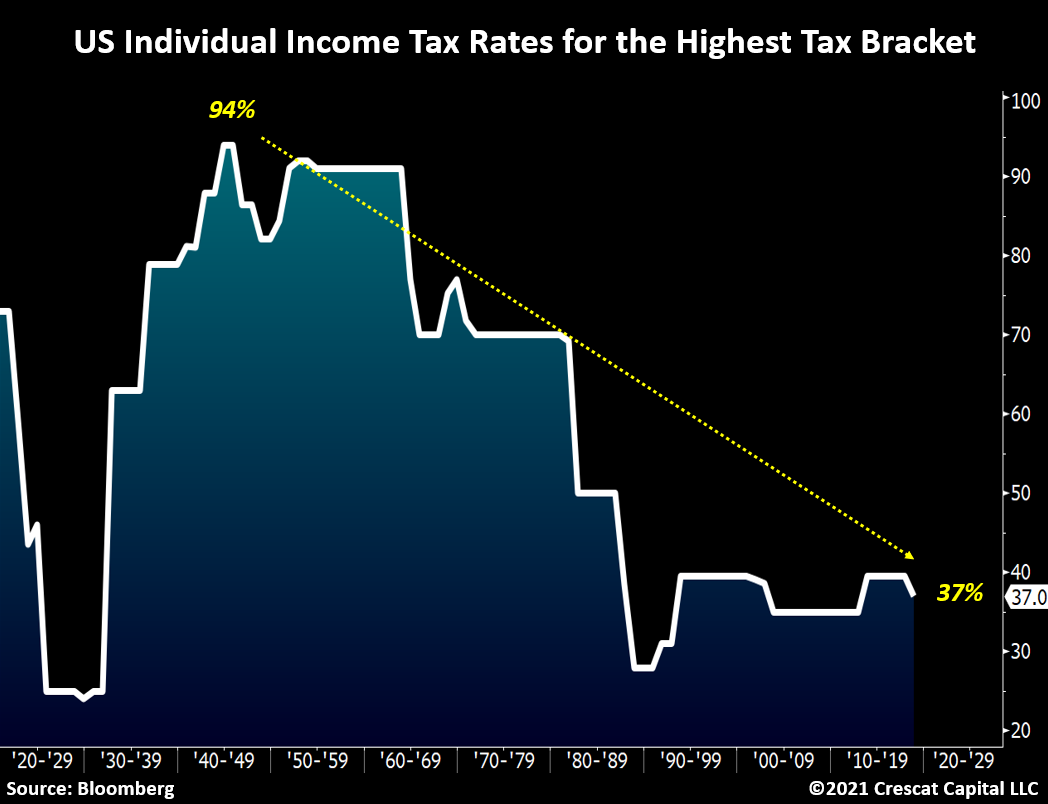

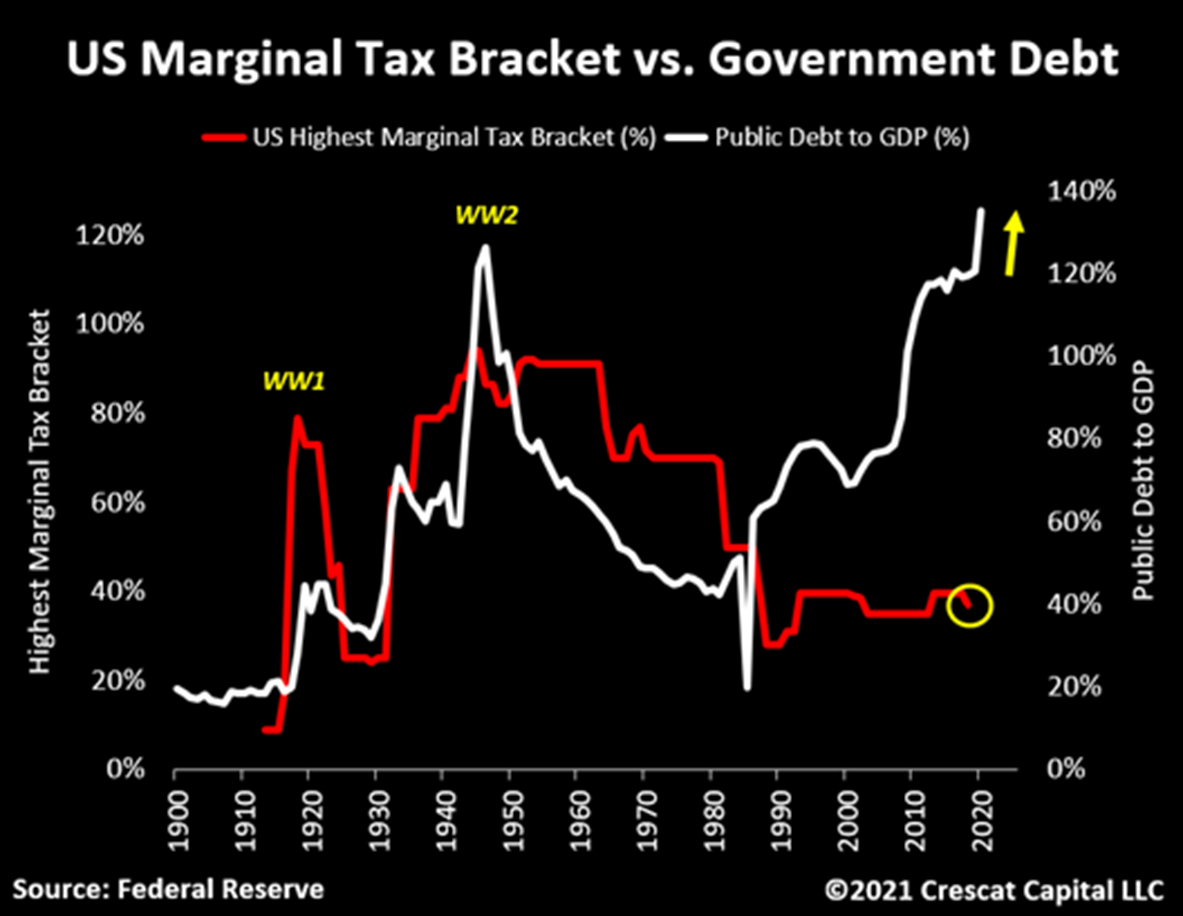

Even from an individual income tax perspective, today’s policies are far more excessive.

Let’s use the decade of the 1940s again for comparison.

The tax rate for the lowest bracket increased from 4% in 1939 to 23% at its most extreme in 1945, which is more than twice where it is set today.

Additionally, the tax rate for the highest bracket was 82% at its lowest level for the 1940s decade. It reached as high as 94% in 1944, which compares to 37% today.

Yes, today’s tax policies may not be sustainable. Throughout history, tax revenues relative to GDP have tended to follow government debt levels. Today is the first time we are seeing such a large divergence between the two.

However, given the need for fundamental growth to justify today’s historic valuations in risky assets, one would wonder how meaningfully the government could really reverse these tax policies.

Here is another perspective to prove our point.

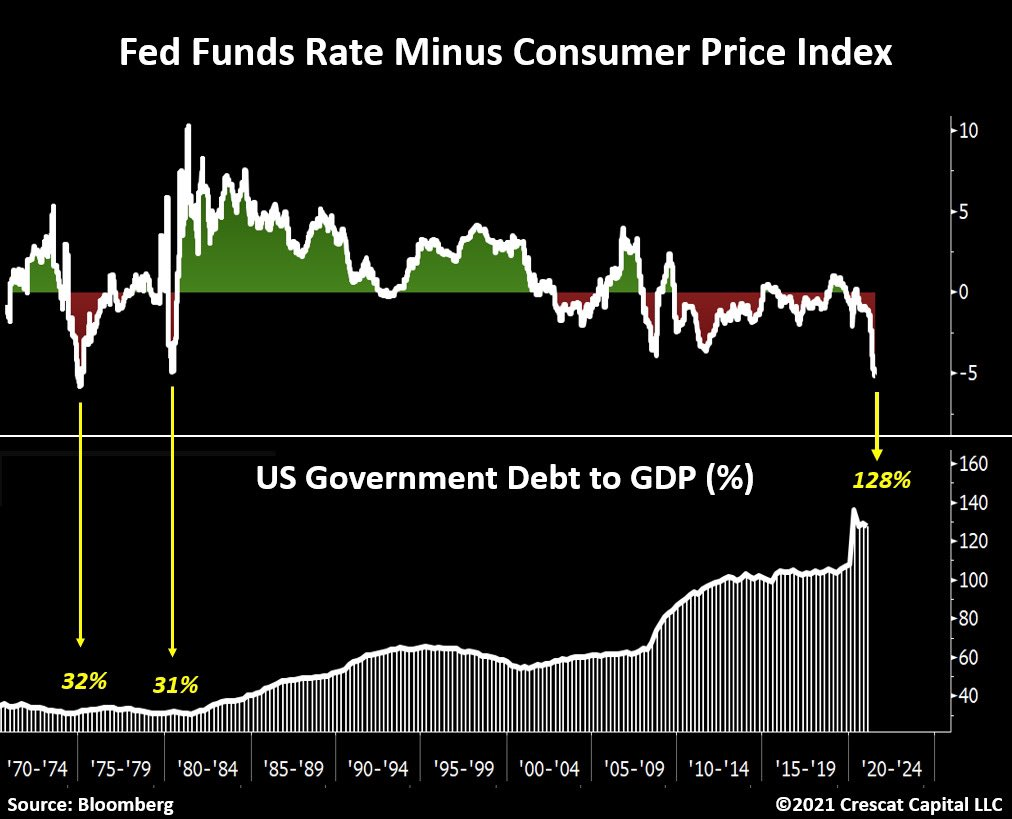

In 1973, when CPI was on an upward trend and reached 5%, the Fed also called it “transitory” but still raised interest rates from 7% to 13%. Note that back then, the government debt to GDP levels were only 32% versus 128% today.

If inflation ever becomes a more persistent problem, what could the Fed even do? Shock the world and raise rates by 2%?

It cannot even do that at the current levels of debt or at these insane valuations for risky assets. The world believes high asset prices are dependent on low interest rates. Our analysis shows they are even more dependent on low inflation, and that is the Fed’s predicament.

Entirely different from today, the government and institutions of the 1970s were fully cognizant of the risk of inflation becoming an uncontrollable problem.

Here is what Richard Nixon wrote two years after announcing the end of the gold standard:

“…everything that the government gives out with one hand it must take back with the other, in higher taxes or more inflation or both. Spending proposals must be looked at in this way, by asking whether they are worth either of these costs. Much government spending fails this test.”

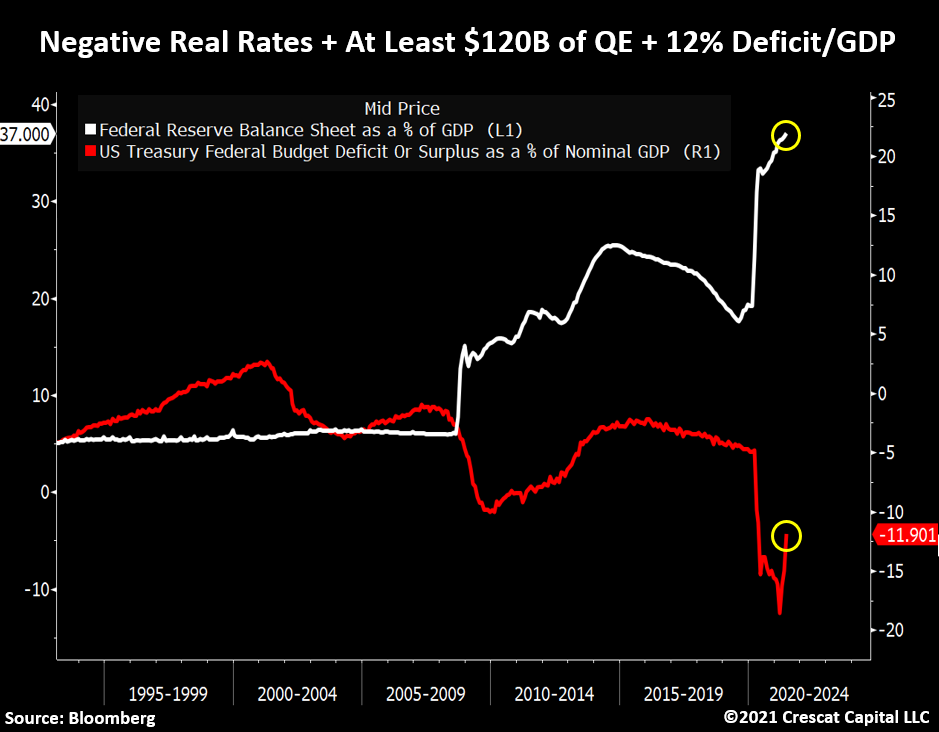

Today, in contrast, the most common refrain we hear from policy makers is that they have not done enough. Therefore, we shall proceed with at least $120 billion/month of QE, 0% interest rates, and 12% government deficits relative to GDP.

The macro imbalances today are extreme, and the ultimate inflationary consequences of years of reliance on ever greater monetary and fiscal stimulus as the primary policy tools to solve economic problems are inescapable.

While some people like to say that the inflation rate will accelerate in steady fashion, we believe this line of thinking is utterly wrong.

Macro forces are cyclical.

As inflation gradually becomes the prevailing narrative, households and businesses act accordingly creating a vicious cycle that can result in surprising surges in the cost of living that ebb and flow.

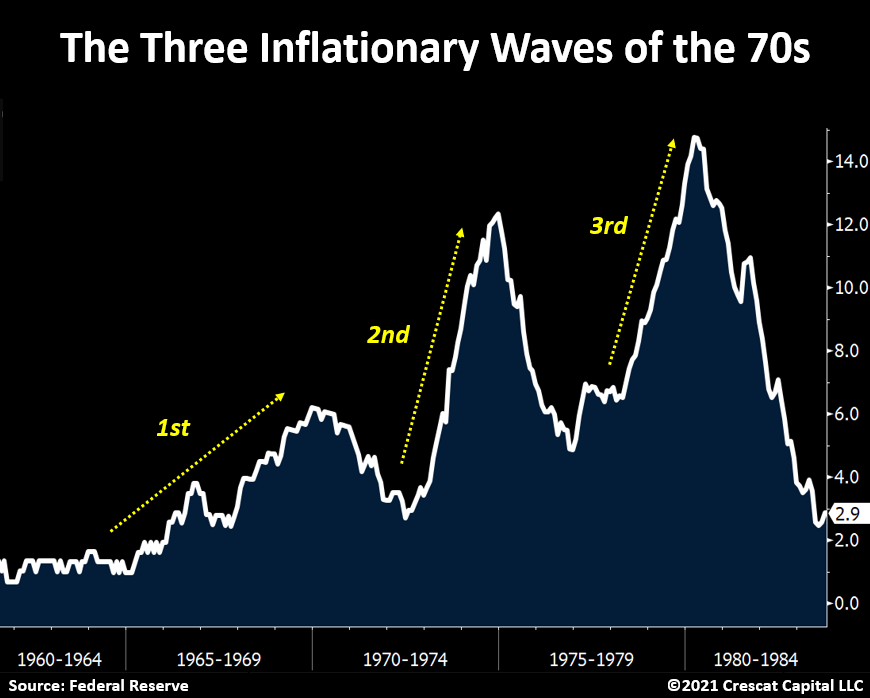

Let’s return to the 1970s case study.

From 1965 to 1980, the US economy experienced three inflationary waves that built on themselves becoming progressively larger as time went on. Note how CPI made “higher highs” and “higher lows” marking a persistent 15-year trend of a rising annualized inflation rate.

This historic fact is exactly the opposite of what is implied by the popular “inflation-is-transitory” narrative today.

That idea implicitly promotes a concept that inflationary cycles are short-term and mean reverting rather than long-term and trending.

Those years were marked by fierce counter shifts in monetary and fiscal policies that repeatedly changed focus from fostering economic growth to strongly fighting inflation.

As a result, financial markets experienced one of the most volatile boom-and-bust periods of history. At that time, the Fed was fortunate to be able to raise rates without triggering a debt crisis.

This is a very different setup today.

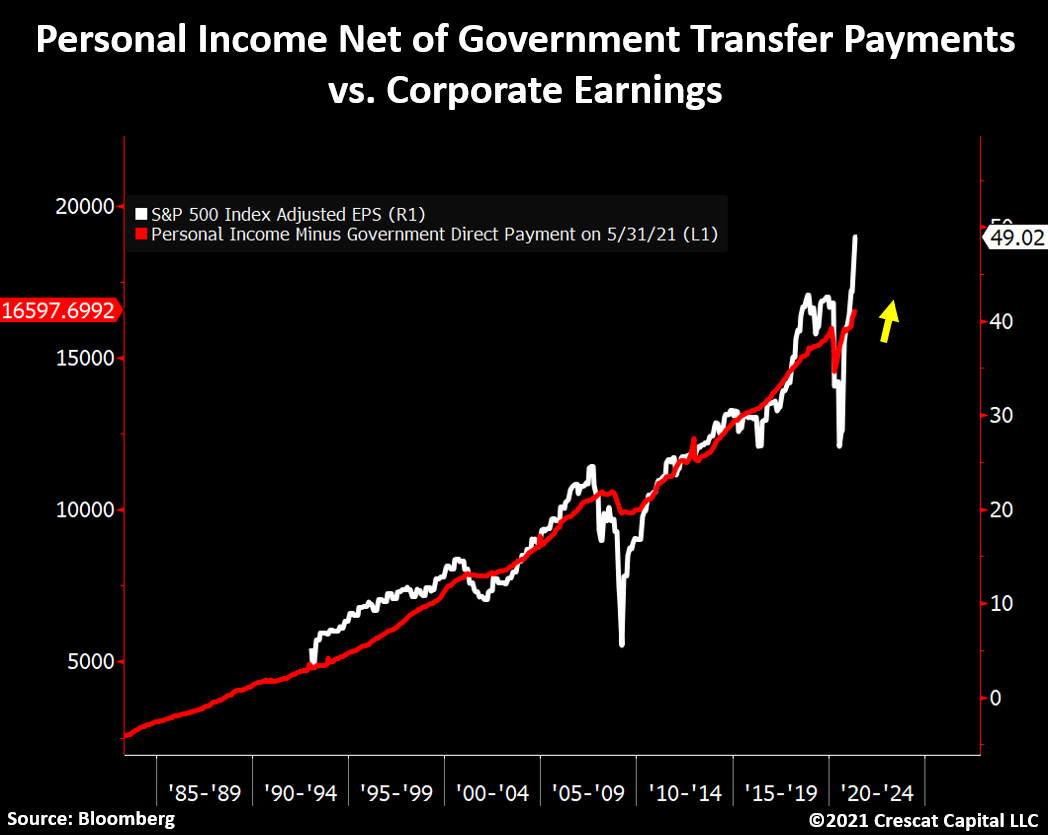

The chart below could not illustrate more meaningfully our current conviction in the inflationary thesis. Through monetary and fiscal policies, the historic amounts of liquidity recently added to the economy have translated into one of the hottest economic environments we have ever seen.

Consequently, corporate profits surged by 47% on a year over year basis and are now significantly higher than any other prior peak. As illustrated below, personal income less government transfer payments tend to follow the bottom-line fundamentals of companies incredibly close.

To us, it suggests that personal income is about to drastically increase in the next quarters.

We think it is going to be driven by a large increase in labor cost.

After experiencing a secular decline in wage and salary growth for the last 30 years, we believe there is a structural shift upon us that will critically feed into the inflationary thesis.

Using our prior analytical work on the 1919 Spanish Flu period as a roadmap, when the cost of living becomes significantly more expensive, workers began to demand materially higher wages.

To recall, in the wake of that pandemic, one out of five people in the US work force was engaged in a labor related strike.

We believe a similar pattern is developing today.

The economy is likely at the early stages of an upsurge in labor-management conflict. In fact, we have not seen an increase in the federal minimum wage since July 2009.

When the first numbers on personal income were reported, economists warned that a significant amount of it was related to the stimulus checks and other fiscal programs.

They were not wrong. To be exact, today government transfer payments represent over 20% of personal income and reached 33% at their peak in March 2021.

As a result:

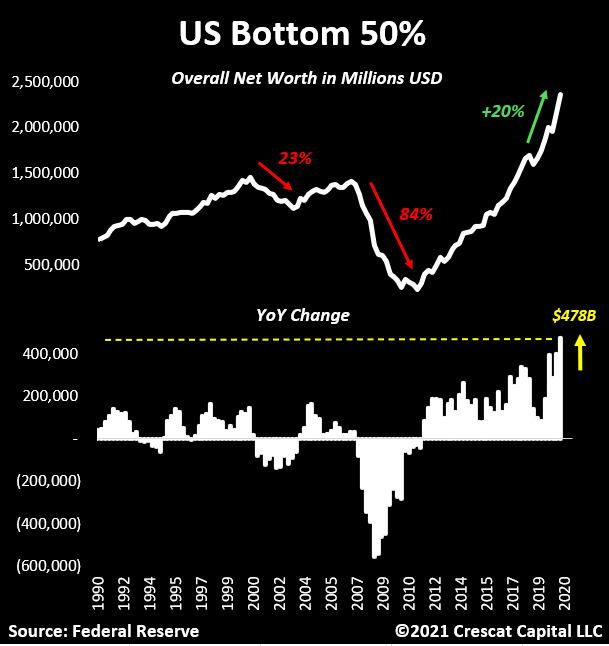

US households just experienced their largest wealth increase in history, including the bottom 50%. This was already accompanied by a significant amount of inflation, even if CPI is understated due to government-sponsored fudging.

But in our view:

If rising personal income is further driven by a new secular rise in wage and salary growth, it would considerably add to the inflationary thesis through a demand-pull dynamic, one that ultimately feeds the classic wage-price spiral.

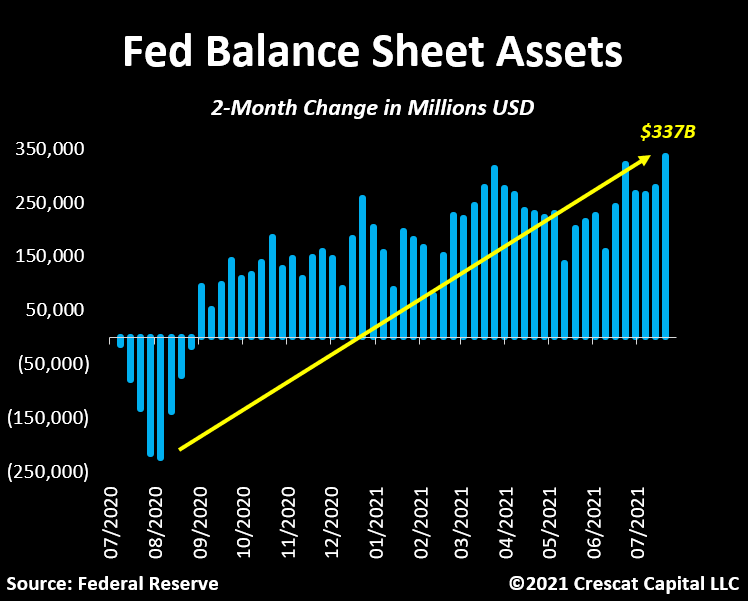

The craziest part of all of this is that monetary policy is gradually expanding.

Contrary to the taper talk, in the last two months alone, the Fed’s balance sheet increased by $337 billion, the largest amount in over a year.

So, with today’s environment being far more extreme than the 1940s and 1970s, does it mean that we are on the cusp to triggering hyperinflation?

That is not our view.

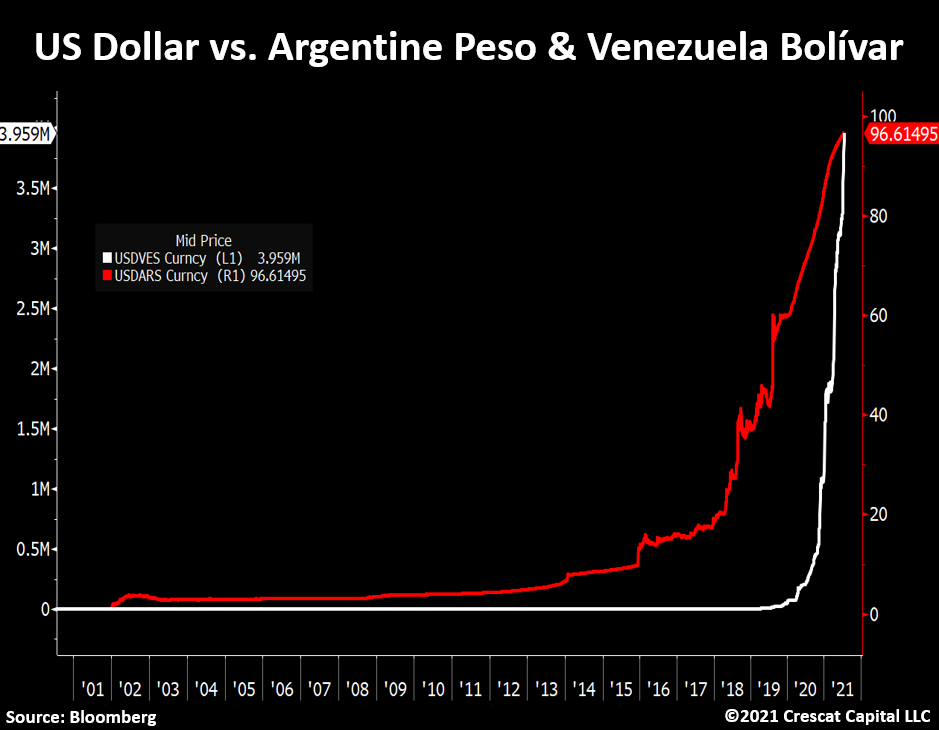

Those are extreme scenarios that start to develop when an economy experiences severe capital outflows, particularly from large businesses and institutions, which leads to a sequence of events.

First, the capital flight creates downward pressure on the local currency, increasing the likelihood of an inflationary problem. Also, as large corporations exit those countries, the labor market suffers, economic growth turns negative, and the instability of the currency is aggravated. The combination of an economic and currency crisis is what leads to social unrest, major political shifts guided by populist agenda, and a major move in opposition to capitalism.

The good news is that these issues take time to evolve, sometimes decades.

Aside from the obvious case being Venezuela, we think Argentina could unfortunately be going towards this path.

Notably, the two currencies are in two different axis, but the exponential appreciation of $USD vs. the $ARS and the $VES is clear.

To be clear, we are not seeing these signs in the US yet.

Almost all major corporations in the world continue to be based here and do business with the US economy.

Therefore, a hyperinflationary scenario is not in our minds as of now.

We think that the inflation rate will continue to rise and be more persistent for longer, the exact opposite of the concept that the Fed is promoting today by characterizing inflation as “transitory”.

We think, like the 1970s, we will see progressively larger inflationary waves that will build on themselves and set off important changes in market leadership and asset allocation.

In this macro backdrop, we believe natural resource industries and their underlying commodity prices will become one of the main beneficiaries. The scarcity of investable assets that yield above inflation expectations is slowly forcing capital allocators out of risky overvalued financial assets and into cheap hard assets.

Meanwhile, there is a clear lack of appreciation by policy makers of the amount of time, capital, skilled labor, and effort that it takes to extract and produce commodities. The green agenda, and the move toward electrification, is grossly miscalculating the need for critical commodities to make this transition possible.

Massive infrastructure developments through fiscal programs are unimaginable without high demand on natural resources in scarce supply.

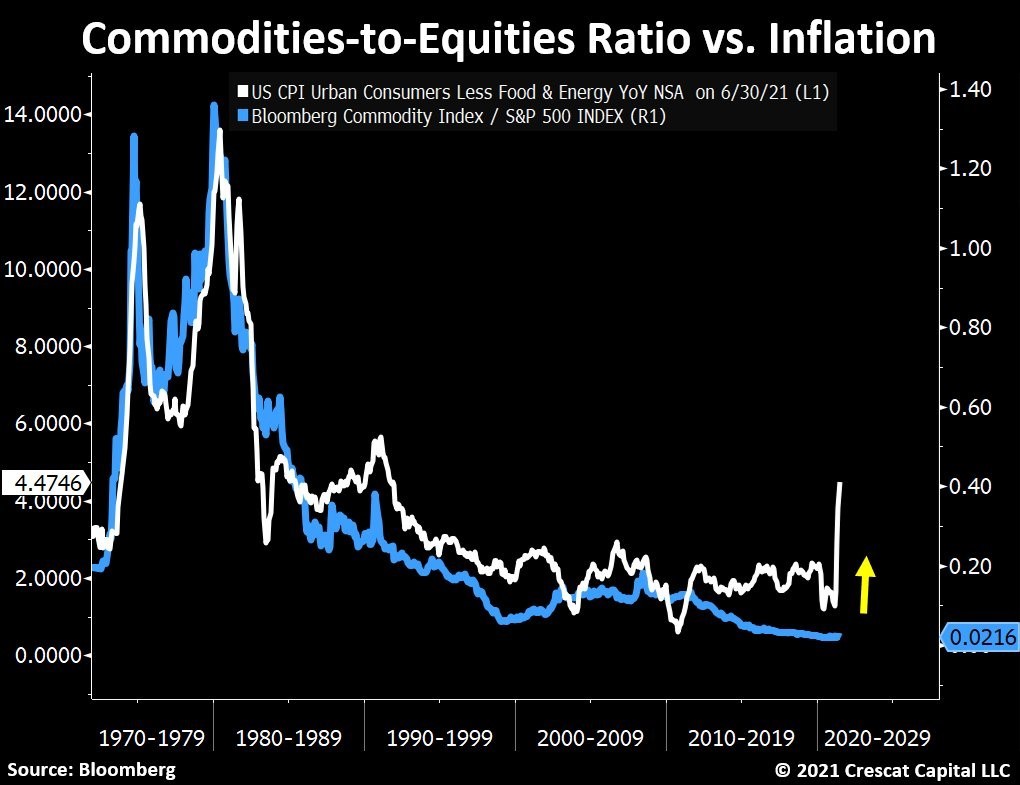

Note how the commodities-to-equities ratio, or what we may call the “tangible-to-financial assets ratio”, tends to follow inflation incredibly close throughout history.

Given our strong views about the likely longer-lasting inflationary consequences in the economy, we believe this is the time for investors to be long tangible assets and short hyper-overvalued stocks while also avoiding bonds.

Keep in mind, commodities remain under-allocated by institutions while stocks now have negative real earnings yield just like bonds.

In our view, it seems largely inconsistent for fiscal and monetary policies to be pedal to the metal at a time when economic activity is at one of its strongest levels in history.

In a way, however, some of the current policies are unavoidable.

With overall debt at historic levels and stocks and bonds at excessive valuations, stimulative policies must be targeted towards suppressing the cost of capital.

We think this macro environment is what makes commodities, especially monetary metals, to be at a uniquely optimistic setup.

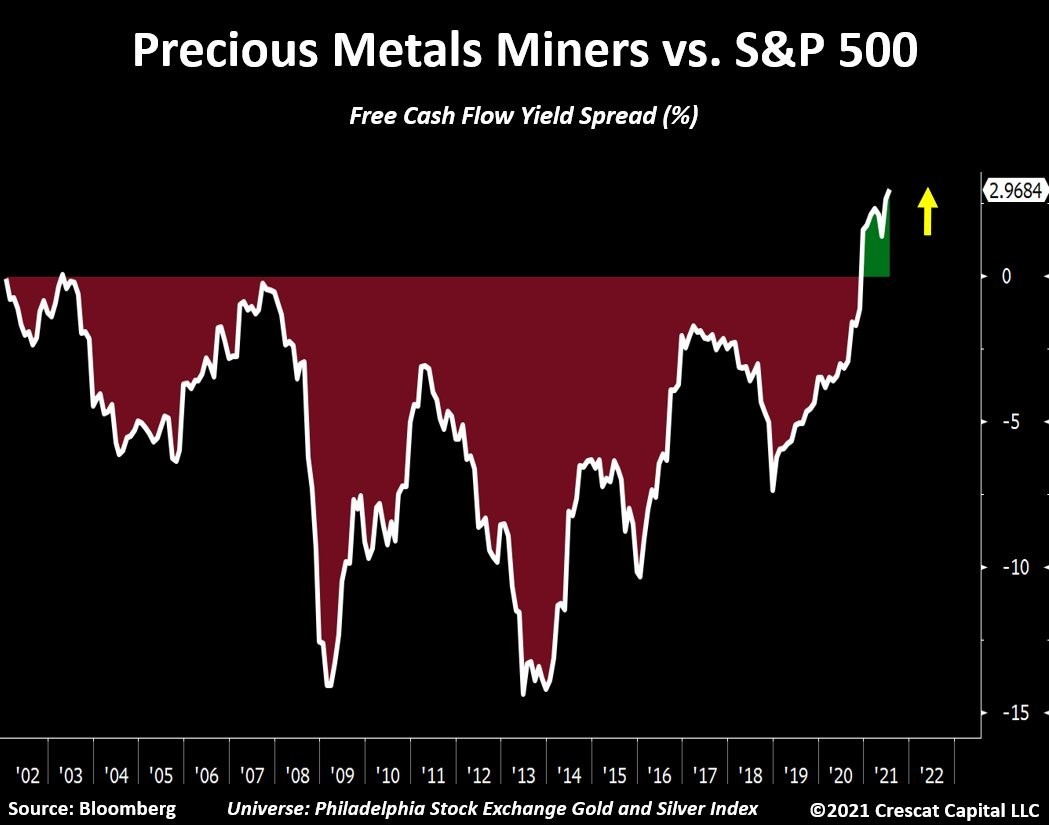

Gold and silver miners have never looked this cheap relative to the S&P 500. Their free-cash-flow yield is almost twice the overall market. The value and growth proposition embedded in miners today is unmatched by any other time in history.

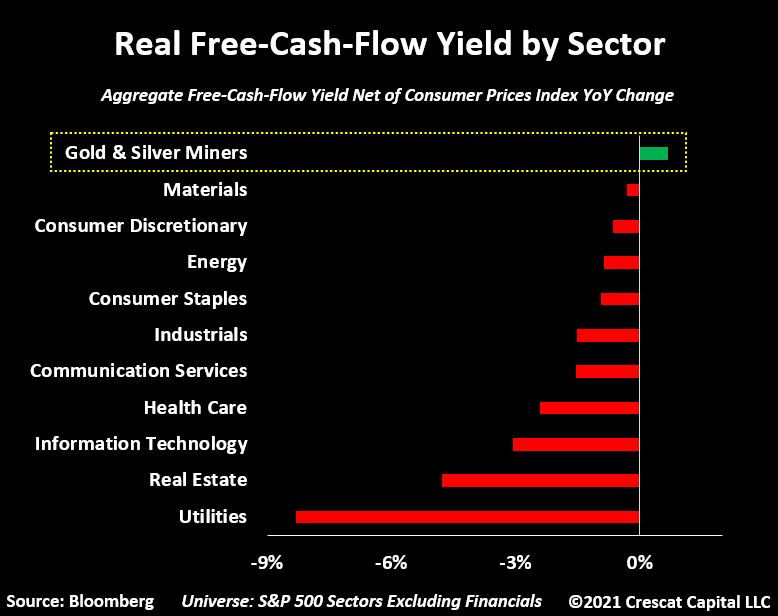

To follow up on this idea, if gold and silver miners were considered a sector, it would be the only part of the economy today that generates higher free-cash-flow yield than inflation.

So how are we positioning for this?

We are leading the charge to fund exploration and discovery of the new, large, high grade deposits of precious and base metals to fill the supply void left by the major mining companies after a decade of underinvestment in exploration and development.

The major metal producers have not been replacing their reserves and are facing a production cliff beginning in just four years.

Permitting new mines takes years.

The industry leaders will need to start allocating capital soon to the best projects out there in the hands of the junior mining segment if they want to continue their growth.

We believe a new M&A cycle will be ramping up soon as the larger producers are now gushing free cash flow that must be deployed to capture growth in the burgeoning new secular bull market for precious metals.

Hope you enjoyed this long article.

Original source: Linkedin Tavi Costa

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.