This week, Cyrille Jubert published an excellent article on the explosive silver situation.

The silver chart pattern is reminiscent of that seen at the end of 2010:

The gold/silver ratio remains historically high, suggesting a relative undervaluation of silver:

A return to the historical average (67) could quickly propel the price of silver to $40 an ounce.

Tensions in the physical silver market over the past week provide further evidence that we are on the cusp of a new peak.

The silver market has seen a significant increase in the EFP premium, a structure that links futures contracts to physical silver. This phenomenon reflects increased tension between COMEX futures prices (notably the March contract) and the spot price of physical silver.

Let's try to explain this in detail.

The COMEX, based in the USA, is an exchange where silver futures contracts are traded, enabling a price to be set for future delivery. Conversely, the London market, often referred to as London Spot, handles immediate transactions in physical silver. These two markets are usually linked by the EFP mechanism, which enables investors to exchange their futures contracts for physical positions.

The EFP mechanism acts as a bridge between these two markets. For example, an investor holding a futures contract on the COMEX can, via an EFP, convert it into a physical position on the London market.

EFPs (Exchange For Physical) are a tool for arbitraging between COMEX futures contracts and the London physical market. They capture the price difference between two maturities, for example between the March and December contracts. Under normal circumstances, a futures contract with a longer maturity, such as the March contract, is more expensive than one with a shorter maturity, such as the December contract. This difference is due to the holding premium, which incorporates storage costs, interest rates and the opportunity cost of tied-up capital.

The EFP represents this premium and functions as a time spread. As maturity approaches, this spread tends to diminish naturally, as the costs associated with holding become insignificant.

Banks, acting as market makers, are generally short EFPs. They are betting on the anticipated fall in the spread in order to make steady profits by capturing price convergence.

However, over the past week, the EFP premium has risen considerably, beyond normal levels.

The EFP (Exchange For Physical) spread is currently 105 points, indicating that the COMEX futures price is $1.05 per ounce above the spot silver price on the physical market.

There is currently increased demand for COMEX “H” contracts (expiring in March), while interest in the London physical market remains low. This is unusual, as these two markets are generally well correlated via the EFP.

This dynamic is reflected in the price differential between the “Z” (December maturity) and “H” (March maturity) contracts, an indicator known as the Z/H spread. A widening of this spread signals strong demand for conversion mechanisms between futures contracts and physical silver.

This situation reflects unusual tension in the market.

For the banks, this increase in premium poses a problem. As they are short EFPs, they incur increasing losses as the spread widens. This forces them to hedge their positions by buying back contracts, further intensifying the pressure on the market.

This situation indicates tension in the system, which could be linked to increased physical demand or logistical constraints, similar to those observed in 2020.

During the Covid pandemic, the EFP mechanism was severely disrupted. The closure of refineries in Europe interrupted the flow of physical money. At the same time, credible but unconfirmed rumours suggested that the US Mint was massively stockpiling physical silver, increasing demand on the COMEX and reversing traditional flows between London and the United States.

These disruptions were exacerbated during the Covid crisis by regulatory differences between the markets, a phenomenon known as “regulatory arbitrage”. These divergences exacerbated imbalances, highlighting the shortcomings of cross-delivery mechanisms between COMEX and London.

In 2020, the increase in the EFP spread was therefore mainly due to physical constraints, such as refining, transport and production capacities, rather than financial mechanisms. During the pandemic, these factors caused major disruptions, highlighting the system's vulnerability to logistical and regulatory shocks.

What's the situation today? Is there a risk of physical delivery?

Some observers believe that the recent increase in EFP is directly linked to the taxes that the Trump administration is planning to impose on imports. These taxes could have a major impact on the logistics and costs associated with the delivery of physical silver, particularly for bars from China.

To understand this dynamic, it is essential to point out that the COMEX, located in the United States, is one of the main markets for trading silver futures contracts. These contracts can be converted into physical silver through the EFP mechanism, which often involves the delivery of standardized bars. A large proportion of these bars are produced in China, a major player in the refining and supply of precious metals.

Trump's new taxes could complicate the import of these silver bars by increasing their costs. It would become more difficult and costly to supply the silver needed to honor futures contracts on the COMEX. As a result, market players could demand a higher premium to compensate for these additional costs, which would explain the increase in the EFP spread.

This problem is all the more crucial as the EFP mechanism relies on a fluid interaction between international markets. Any trade barrier, such as a tax, upsets this balance by increasing costs and slowing down deliveries. It could also create a temporary scarcity of physical silver on the US market, putting further pressure on the EFP. In short, these potential taxes complicate the supply chain and contribute directly to the widening of the EFP spread.

This short-term problem comes at a time when more and more studies anticipate a structural silver deficit by 2025.

Demand for photovoltaics continues to grow, particularly in China. Record solar panel installations in 2023 are expected to continue into 2025, supported by innovations such as TopCon cells.

Strong demand for physical silver... but also strong demand for physical gold.

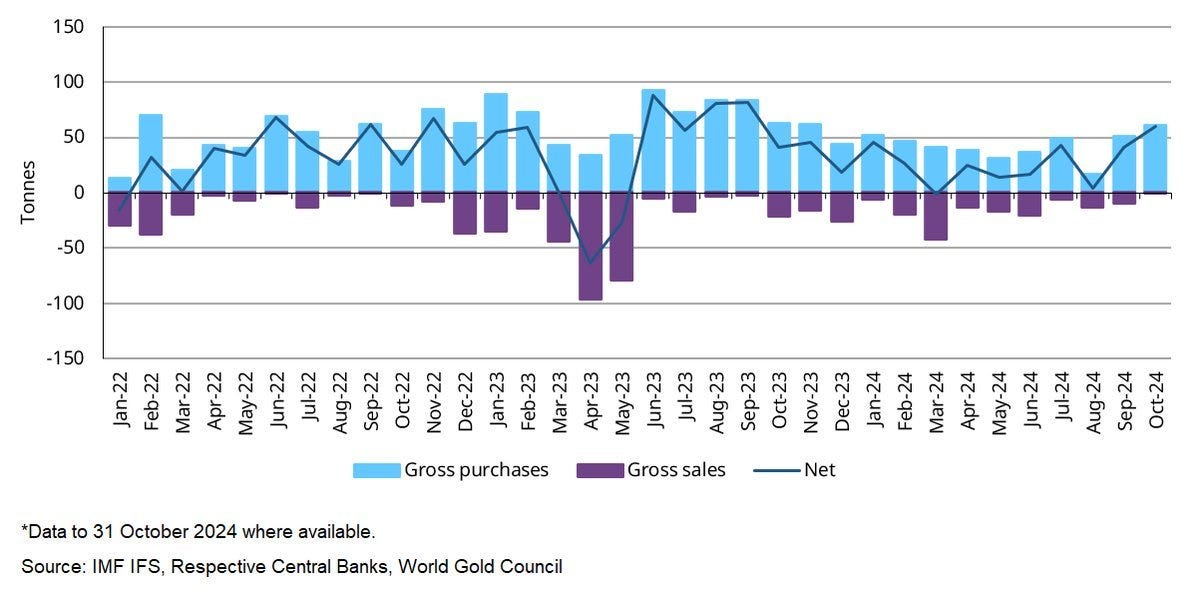

Central banks bought 60 tonnes of gold in October, their largest net monthly acquisition in 2024. Since the beginning of the year, they have accumulated a total of 694 tonnes of gold, a level comparable to that of 2022:

Moreover, China resumed its gold purchases in November after a six-month pause. India and Turkey purchased 77 and 72 tonnes of gold respectively this year. The National Bank of Poland (NBP) also bought a record 21 tonnes of gold in November, taking advantage of the correction period. Poland's gold reserves now stand at 448.2 tonnes.

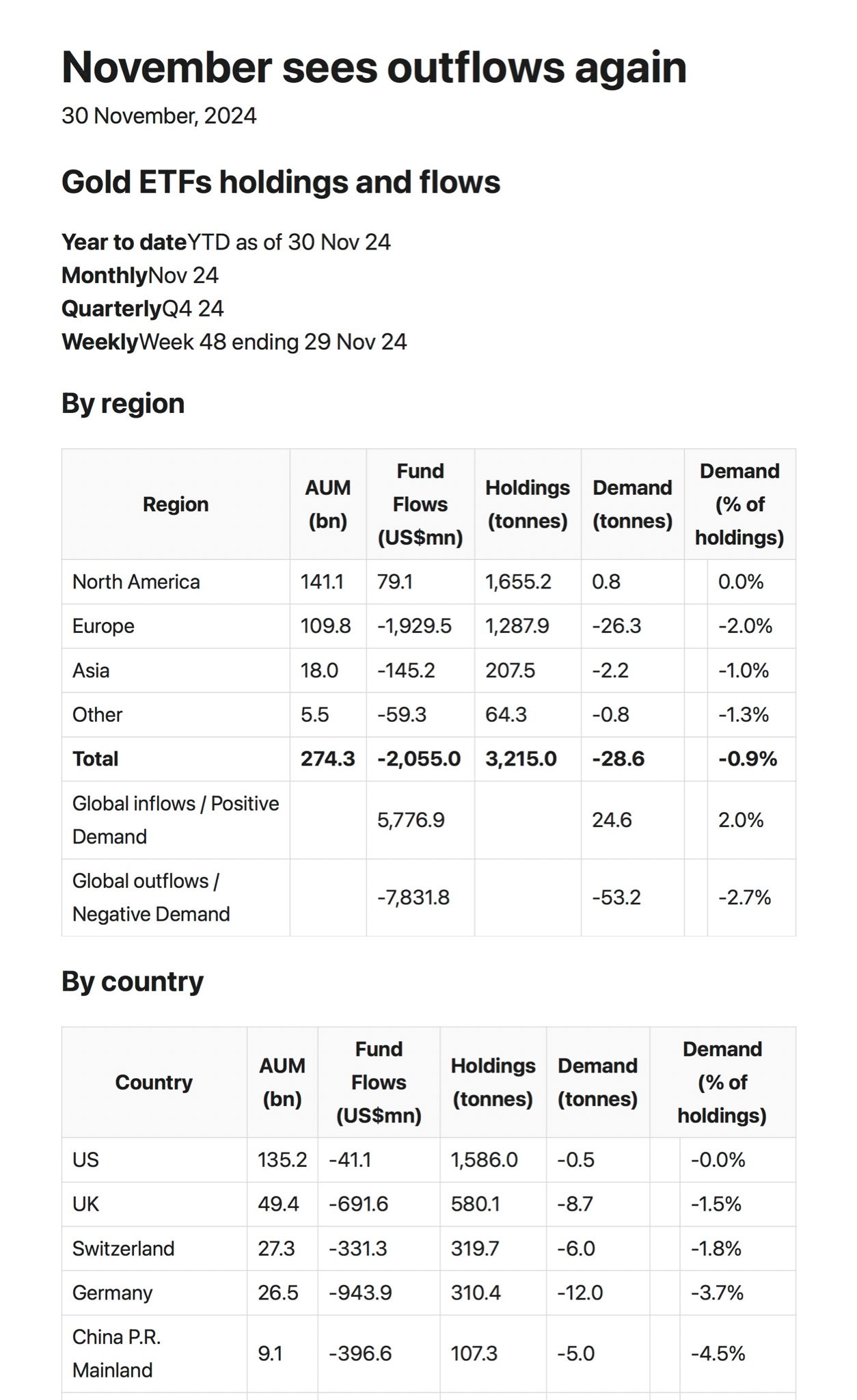

Central bank purchases of physical gold, as well as tensions on the silver market, are taking place against a backdrop of general indifference on the part of Western investors.

Despite gold's all-time highs, ETF assets backed by this precious metal continue to decline, particularly in Europe:

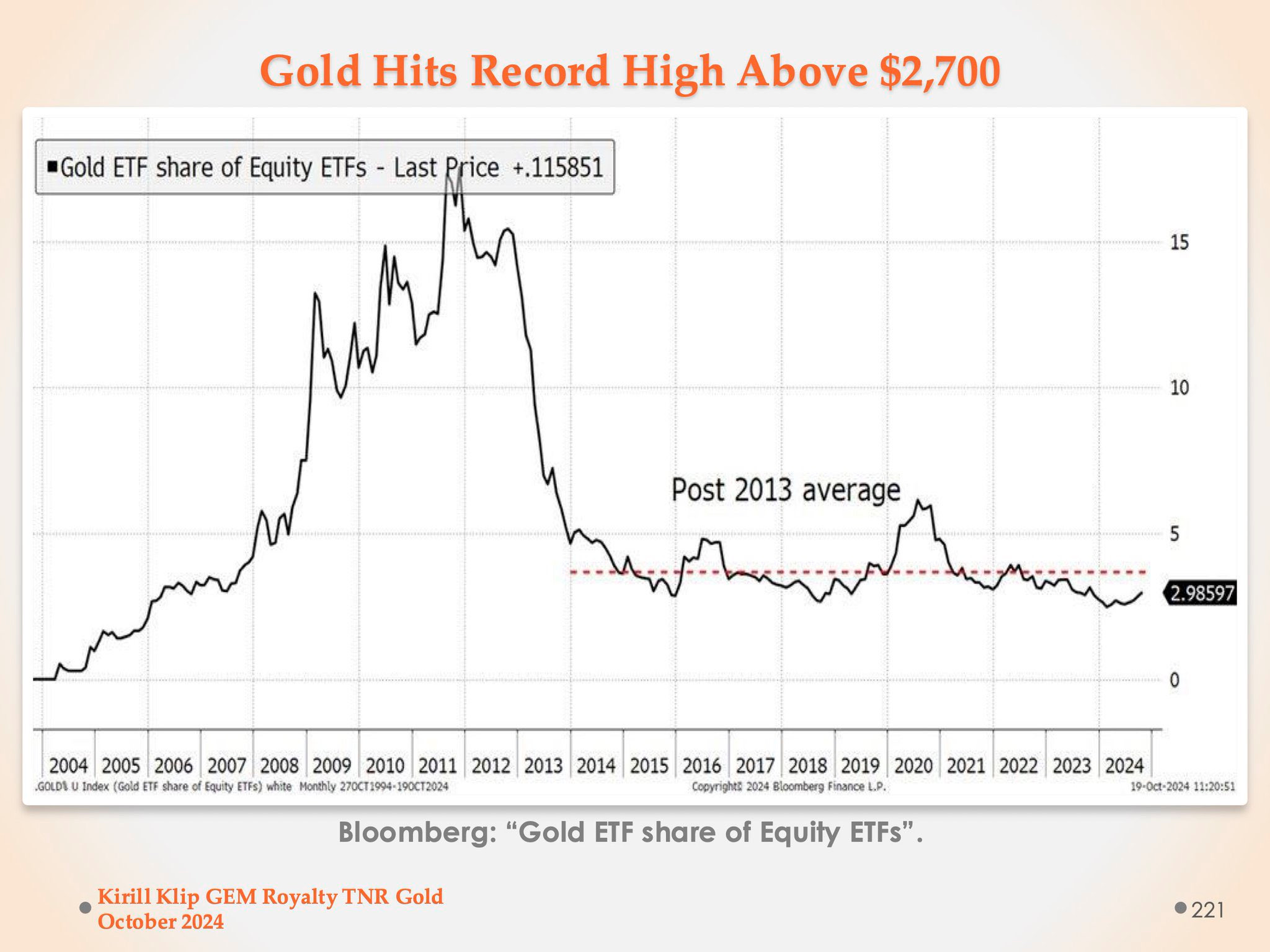

Despite the spectacular price rise, gold-backed ETFs as a proportion of all ETFs on the market are at their lowest level since 2006:

Western investors are currently favoring other types of ETFs, including those focused on equities, bonds, or fast-growing sectors such as technology, cryptocurrencies or artificial intelligence.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.