Donald Trump's recent change of tone on tariffs, like his unexpected softening towards Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, highlights an often overlooked reality: the real balance of power isn't played out on the political stage, but in the workings of the US debt market.

In other words, even under the presidency of a man with a reputation for unpredictability and interventionism, the trajectory of American policy remains profoundly constrained by the demands of the bond market. This debt wall, i.e. the colossal scale of the U.S. Treasury's refinancing needs, imposes a de facto discipline. As soon as long-term interest rates soar or demand for Treasuries falters, any attempt at political independence or institutional confrontation comes up against the reality of global financial flows.

Trump, seemingly free to make his own choices, finds himself forced to adapt his discourse - not out of conviction, but under the silent pressure of the markets. He cannot sustainably oppose the Fed or adopt excessively deviant trade or fiscal policies without immediately paying the price on the bond market. The slightest tension between the White House and the Fed is enough to push up risk premiums, increase borrowing costs and threaten a balanced budget.

This strategic about-turn illustrates the extent to which markets - and sovereign debt markets in particular - now dictate the limits of executive power. What looks like a political tug-of-war actually conceals a delicate balancing act, with the real political center of gravity shifting towards the yield curve.

Behind the volatility of financial markets and the apparent tumult of economic policies, it is in reality the market for long-term interest rates that holds the decisive power. Contrary to popular belief, these rates are largely beyond the central bank's direct control: they reflect investors' expectations, fears and demands.

While the Fed can influence short rates, its influence on long rates remains indirect and conditional. It can only hope to bring them down by giving strong monetary signals - in particular, by cutting its key rates, as Donald Trump would like.

And therein lies the paradox: the US President is hoping for an easing in long-term interest rates to lighten the burden of federal debt and boost activity... but is discovering that this easing cannot be decreed. It depends on a factor that neither the White House nor even the Fed can fully control: market confidence. And when that confidence wavers, long rates become an autonomous force, dictating terms to politics rather than the other way round.

So, despite some easing of trade tensions - notably Trump's reversal on tariffs - and a slight rebound in equity markets, the long-rate market remains under pressure.

The recent correction in the financial markets has not been kind to US sovereign bonds - quite the contrary. During the previous major upheavals, US Treasuries had fully regained their safe-haven status: investors rushed to buy them, causing yields to fall sharply, particularly on the 10-year.

This movement was explained by a need for absolute security against a backdrop of a general collapse in confidence.

But this time, the scenario is radically different. Despite rising risk aversion and growing tensions on equity and credit markets, US 10-year yields are not falling - worse, they remain high, and are even continuing to rise. This phenomenon reveals a profound anomaly: Treasuries are no longer playing their role as a safe haven. This reflects an unprecedented lack of confidence in the American signature itself, or at least in the sustainability of its fiscal path.

In other words, it's no longer just the risk to private assets that's causing concern, but the risk to the very heart of the global financial system.

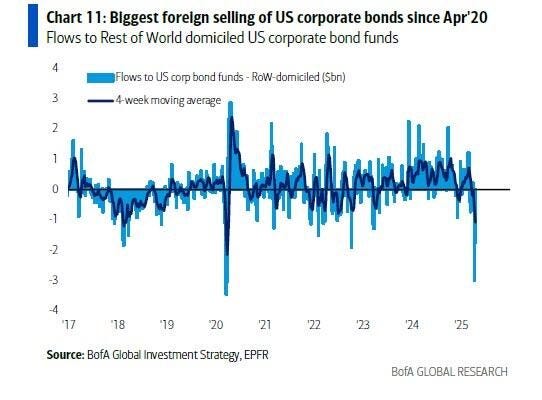

Even the recent violent correction in US corporate bonds has not triggered the traditional pullback towards US sovereign bonds.

Investors, particularly foreign investors, are unloading their US assets on a massive scale, whether in equities or corporate bonds. But, in an unprecedented move, this capital is not being redirected into Treasuries, as might be expected. Rather, it is leaving the US markets altogether.

This behavior marks a break with the usual market mechanics. For a growing proportion of international investors, Treasuries are no longer fulfilling their role as the ultimate safe haven. Whether due to high long-term yields, fiscal concerns or a loss of confidence in monetary policy, the message is clear: US sovereign debt is no longer perceived as the haven of stability it once embodied.

The downward resistance of yields - particularly on 10- and 30-year maturities - reveals a much deeper dynamic than mere nervousness linked to geopolitical news or the Trump administration's decisions.

The problem no longer lies in cyclical volatility, but in a structural questioning of investors' appetite for US duration. Even when equity markets ease or the executive branch tries to stall, investors demand an ever-higher premium to agree to lend long-term to the US government. This persistent skepticism is directly reflected in the persistently high yields on Treasuries, despite political "repositioning" efforts.

This underlines one thing: long rates are no longer sensitive to short-term political or monetary communication. They are now the expression of a more fundamental malaise, linked to the United States' fiscal trajectory, the massive supply of debt to be absorbed, and growing doubts about the institutional anchoring of monetary policy. In this sense, the long rates market has become the silent but implacable judge of the US fiscal mess.

The sustained breach of the 5% mark on the US 30-year yield is not just a technical signal. It marks a shift in the perception of US sovereign risk. Markets now demand a much higher risk premium for holding long-dated debt. This is no longer a reaction to economic conditions, but rather a lack of confidence in the face of a series of structural factors: fiscal drift in the United States, geopolitical tensions, and the weakening of the dollar as a global anchor.

The Fed retains some control over short-term rates, but has lost its grip on the long term. Investors are fleeing duration in favor of real assets (gold, real estate), safe-haven currencies (CHF, JPY) and real-return proxies. This rise in rates is therefore not an anomaly, but an adjustment in global confidence.

A 30-year at 5% does not herald a peak, but a warning: the market doubts the financial and institutional solidity of the United States. Only a break in the trend - a collapse in growth, direct intervention by the Fed, or a massive return of foreign buyers - could reverse this dynamic. Failing that, the markets are reassessing US debt with a fresh, more demanding eye.

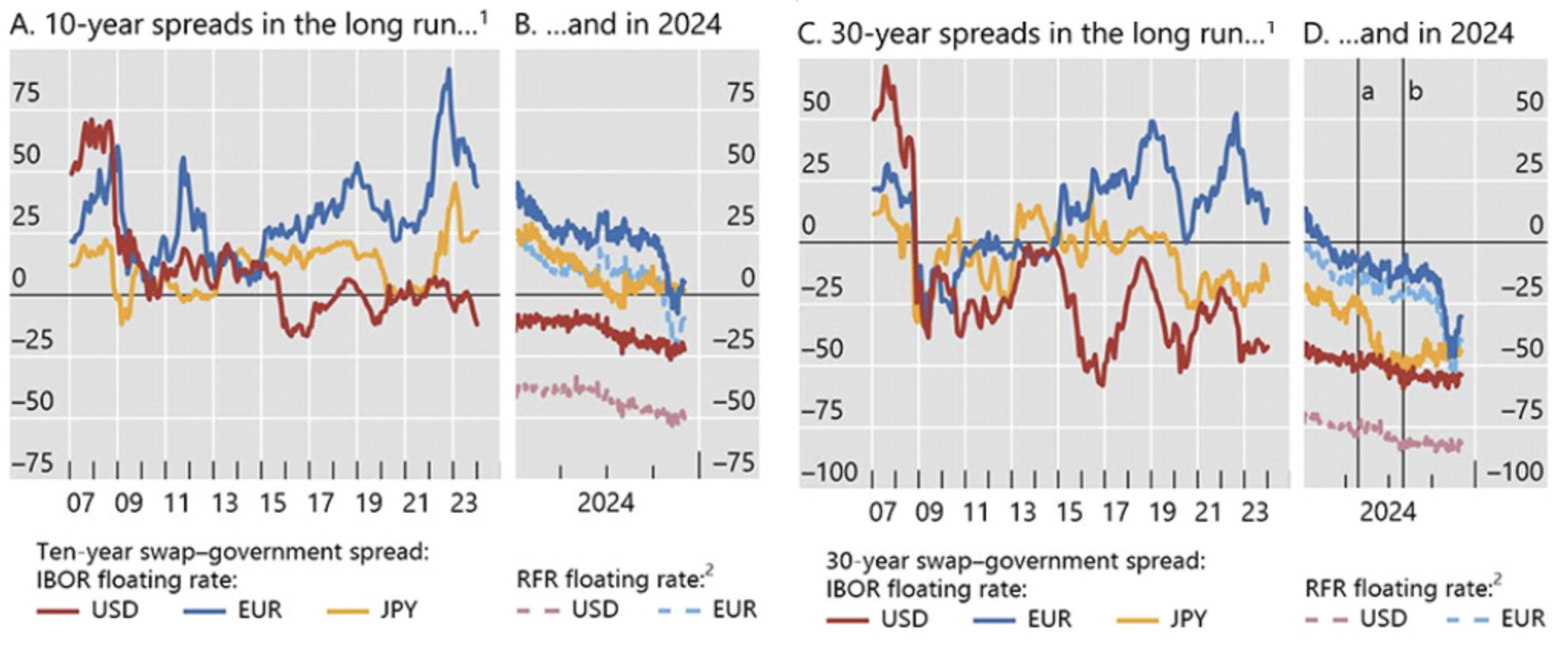

This signal of mistrust in the US 30-year bond - where a breach of the 5% mark embodies a structural loss of confidence in the US sovereign debt - should not be seen in isolation. It is part of a wider dynamic of tensions on the interest-rate markets, of which interest-rate swaps are both the reflection and the vector.

For it is precisely through these derivative instruments - which are supposed to offer protection against interest-rate variations - that a massive arbitrage architecture has been built up, which is now under threat. When the fixed rate of a swap falls below the yield of a Treasury with the same maturity, as is currently the case, this creates an apparent carry opportunity. But behind this opportunity lies a leveraged mechanism, sensitive to the slightest market jolt.

Let's take a closer look at this phenomenon:

Interest rate swaps, key instruments in financial risk management, are at the heart of a latent imbalance in the global bond market. Their operation is based on an exchange of interest flows between two parties: one pays a fixed rate, the other a variable rate indexed to a reference rate such as the SOFR. These contracts enable players to secure their exposure to interest-rate variations, by adapting their risk profile.

When fixed swap rates fall below the yield on government bonds of the same maturity - a phenomenon known as “negative spread” - arbitrage opportunities arise. An investor can buy Treasuries on a long-term basis, finance this position on a short-term basis via the Repo market, and then use a swap to receive a floating rate higher than the fixed rate he is paying. This arrangement, known as a “basis trade”, can generate a positive carry, especially when coupled with a currency carry trade such as zero rate yen financing.

But this seemingly risk-free strategy relies on high leverage and solid counterparties. As soon as the market becomes tense - rising long-term interest rates, more expensive financing, loss of confidence - these arrangements become fragile. The disappearance of a counterparty in a swap, for example, removes the hedge against interest-rate risk, transforming a neutral position into direct exposure to the bond market.

This imbalance spreads by domino effect. Forced sales of Treasuries amplify the rise in long rates, triggering margin calls, further sales, and so on. Instead of normalizing, swap spreads continue to fall, as players are no longer able or willing to take on the other leg of the contract. The system freezes, liquidity disappears and mistrust sets in.

This is precisely what is happening right now. Swap spreads are currently falling dramatically, not only on the 30-year maturity, but also on the 10-year - two crucial segments of the yield curve.

In practical terms, a negative swap spread means that the fixed rate offered in an interest-rate swap is lower than the yield on a government bond of equivalent maturity. In a normal environment, this spread should remain close to zero, as arbitrage forces tend to smooth out the differences between these two instruments. Today, however, this spread is not only becoming negative, but is sinking deeper and deeper.

This fall in swap spreads reflects several concurrent phenomena:

- On the one hand, increased pressure on the balance sheets of financial institutions, which are reluctant to take positions for lack of capacity or risk appetite.

- Secondly, a persistent and structural demand for hedging on the part of players with long durations (pension funds, insurers), seeking to protect themselves against a further rise in long-term rates.

- Finally, a reduction in leverage and a contraction in liquidity in the system, making traditional arbitrage much more costly, if not inaccessible.

In other words, the fall in 10- and 30-year swap spreads reflects more than just a temporary market inefficiency. It reveals a profound imbalance in the functioning of the interest-rate market, which is at once balance-sheet-related, psychological and structural. It's a silent but fearsomely powerful indicator of a system that shrinks in on itself.

In such an environment, even historically robust arbitrage mechanisms become inoperative. Banks, funds and insurers prefer to preserve their flexibility rather than engage in asymmetric risk strategies. The collateral multiplier is shrinking: the same bond can no longer be used as collateral in as many transactions as before. The entire liquidity transformation system contracts.

The situation becomes critical when market tensions intersect with a crisis of governance. If the central bank's independence is called into question, for example by a political attempt to dismiss its president, confidence in the institution's ability to react collapses. International investors may then flee sovereign bonds, pushing up long rates even further. Under these conditions, even a cut in key rates becomes ineffective: markets interpret such a move as a sign of panic.

This phenomenon highlights an often underestimated truth: interest-rate derivatives, although designed to manage risk, can become crisis amplifiers when carried by a system that is overly indebted, overly interconnected, and overly dependent on abundant liquidity. When a link breaks, arbitrages turn against their authors, and the most liquid markets become unstable.

In the long term, only credible, rapid and massive central bank intervention can halt this dynamic. This requires not only technical tools - such as bond repurchases or the extension of financing facilities - but also a solid institutional foundation based on trust. For it is this trust, in counterparties as well as in monetary authorities, that is the real backbone of the markets.

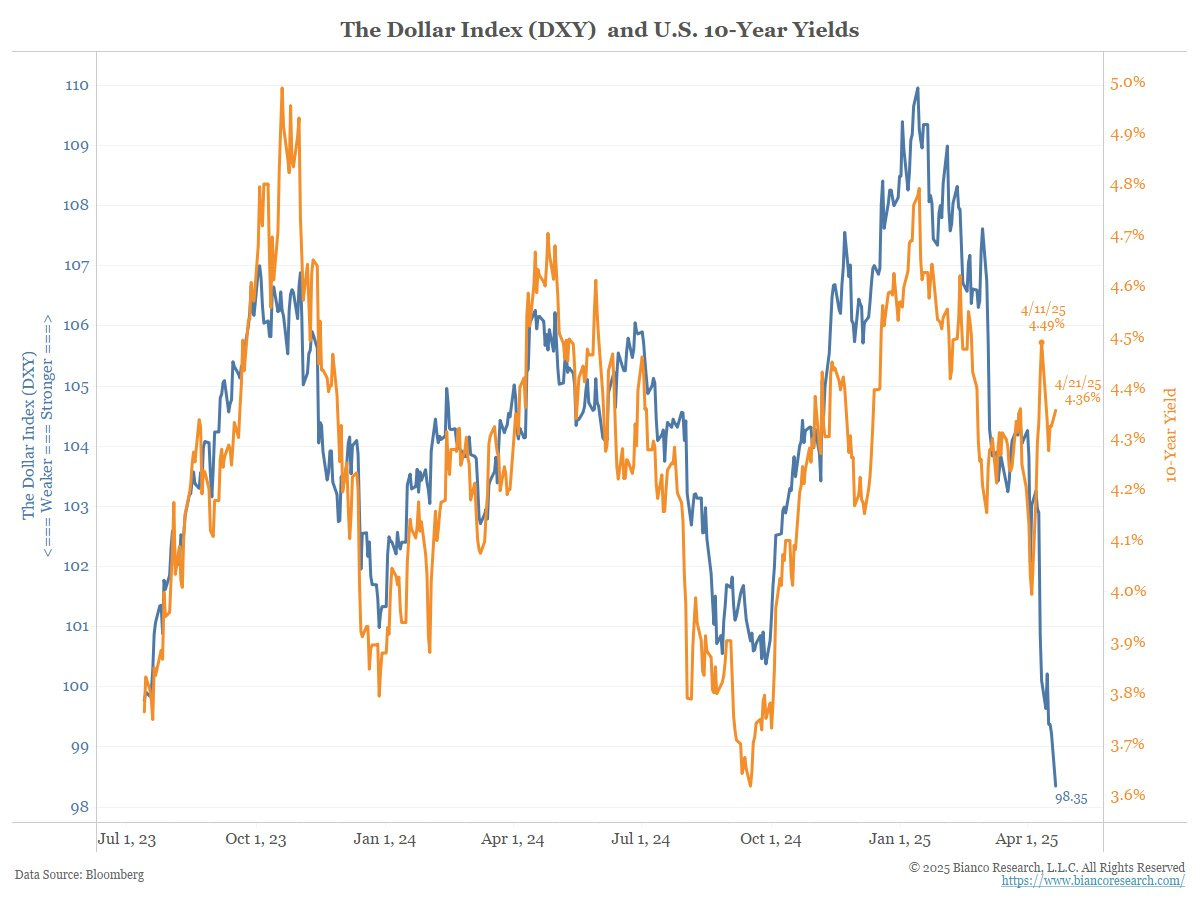

Another indicator of current tensions, highlighted by the tariff crisis, is the unprecedented break between the behavior of the dollar and that of interest rates.

In theory, a rise in US interest rates should strengthen the greenback, by making dollar-denominated assets more attractive to international investors. But this traditional link is breaking down - and that's precisely what's worrying.

The phenomenon is intensifying: even as long rates continue to climb, the Bloomberg Dollar Spot Index (BBDXY), which measures the dollar's performance against a basket of major currencies, has fallen to its lowest level since January 2024. This divergence is a strong signal. It suggests that higher rates are no longer enough to stabilize the dollar, and that, in theory, they would have to be pushed even higher to halt the fall. But such a prospect is difficult to sustain in the current context of economic and financial fragility.

What we're observing here is not just a passing anomaly, but a regime change. A de-anchoring. The market is giving a warning: confidence in the usual monetary policy transmission mechanisms is cracking. Even investors who have faithfully followed the relationship between yields and currencies are beginning to turn away.

And this slide is all the more worrying given that the BBDXY index, which is almost perfectly correlated to the traditional DXY (Dollar Index), is widely followed by professionals. So this is not a marginal or esoteric signal. It's a clear message from the markets: something has gone wrong with the traditional asset hierarchy.

The current market context marks a clear break with previous crises. Firstly, the simultaneous fall in US equities and corporate bonds is no longer accompanied by a flight to Treasuries. Secondly, the collapse of interest-rate swap spreads, particularly on long maturities, indicates a deep and lasting tension within the bond market. Finally, the disconnect between long rates and the dollar reveals growing mistrust of the US monetary anchor.

Under these conditions, it is logical that physical gold continues to play its role as a safe haven. The surge in premiums in China following the recent fall in gold prices shows that demand remains strong. This could quickly put an end to any consolidation phase.

Despite recent shifts in political rhetoric in the United States, systemic risks are still very much with us - and gold is well aware of this.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.