Bank of America's results confirm the scale of the risks facing the US banking system.

Potential losses on the bank's HTM (Hold to Maturity) securities now stand at $131.6 billion, up $26 billion in the third quarter alone. Never before has the bank found itself with such a high level of virtual losses on these hold-to-maturity bonds.

But BoA is not the only institution to find itself in this situation. The increase in interest rates initiated by the Fed has had a devastating effect on bonds, which were massively purchased by banks, insurers and pension funds when rates were low.

The question is whether this fragility in the banking and insurance sector is likely to cause a contraction in credit: Are banks facing significant losses on bond securities being encouraged to reduce lending? Does the new interest-rate environment affect banks' ability to grant new loans? Is the flight of depositors changing lending conditions?

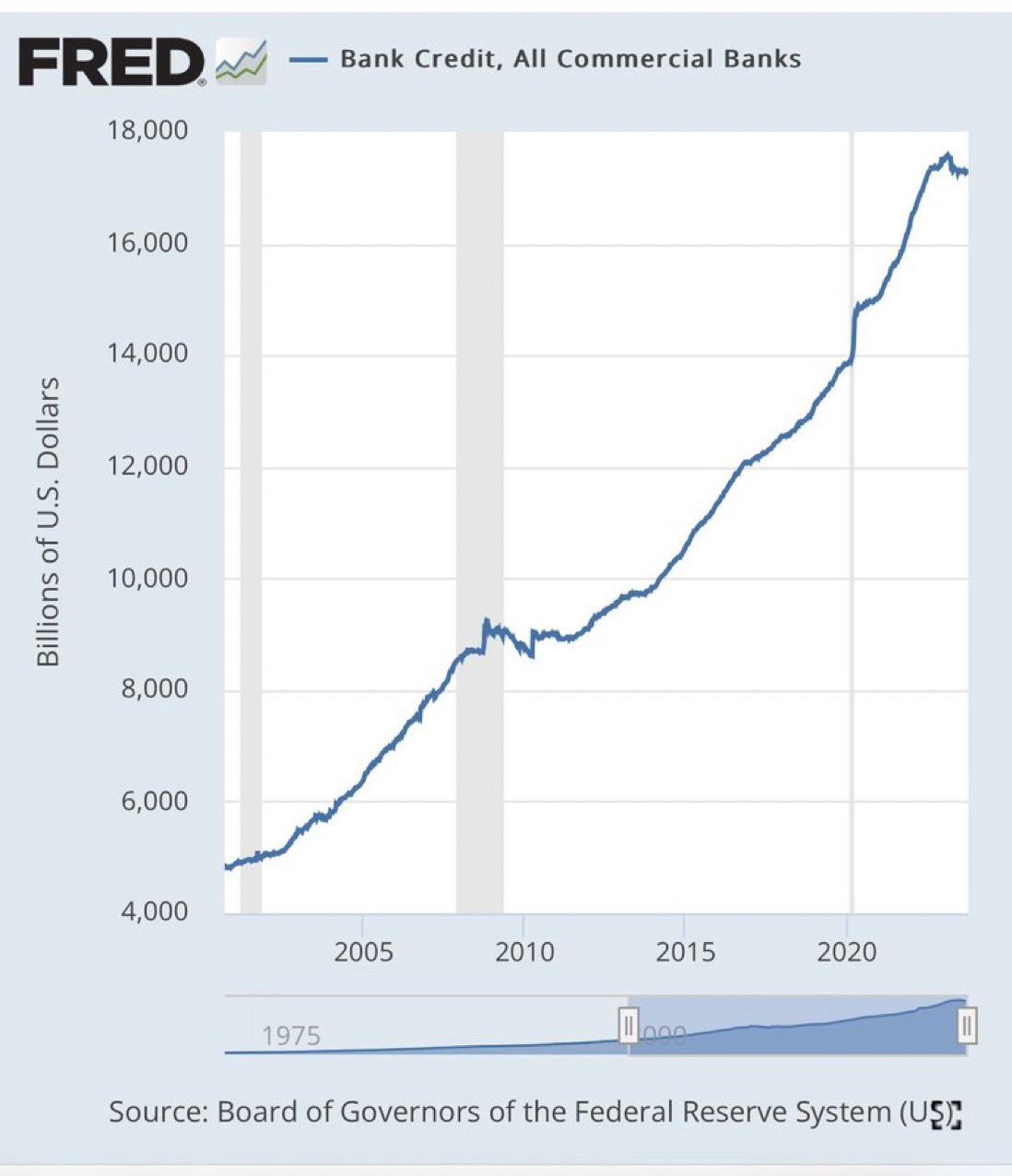

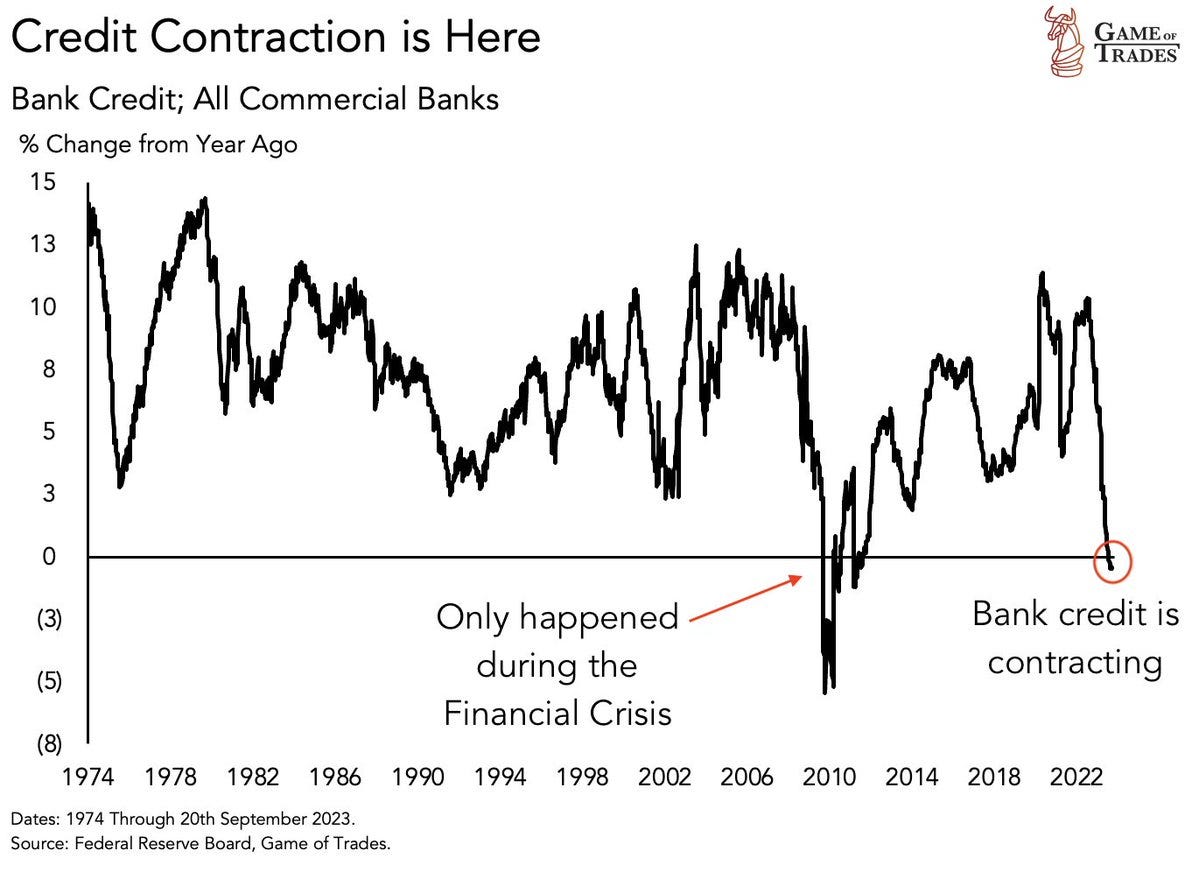

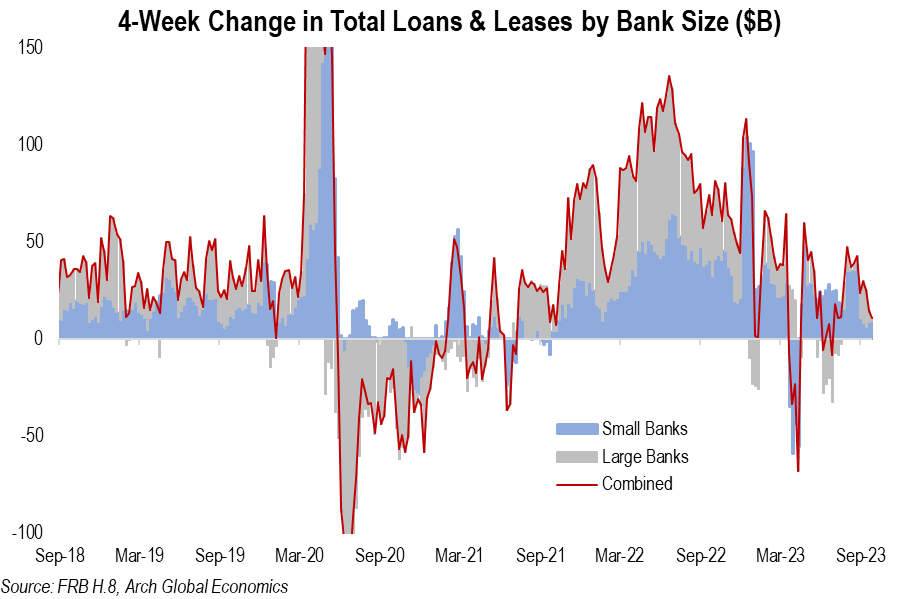

Technically speaking, the credit crunch is clearly reflected in the figures:

For the first time since 2008, banks have slowed lending to businesses and consumers:

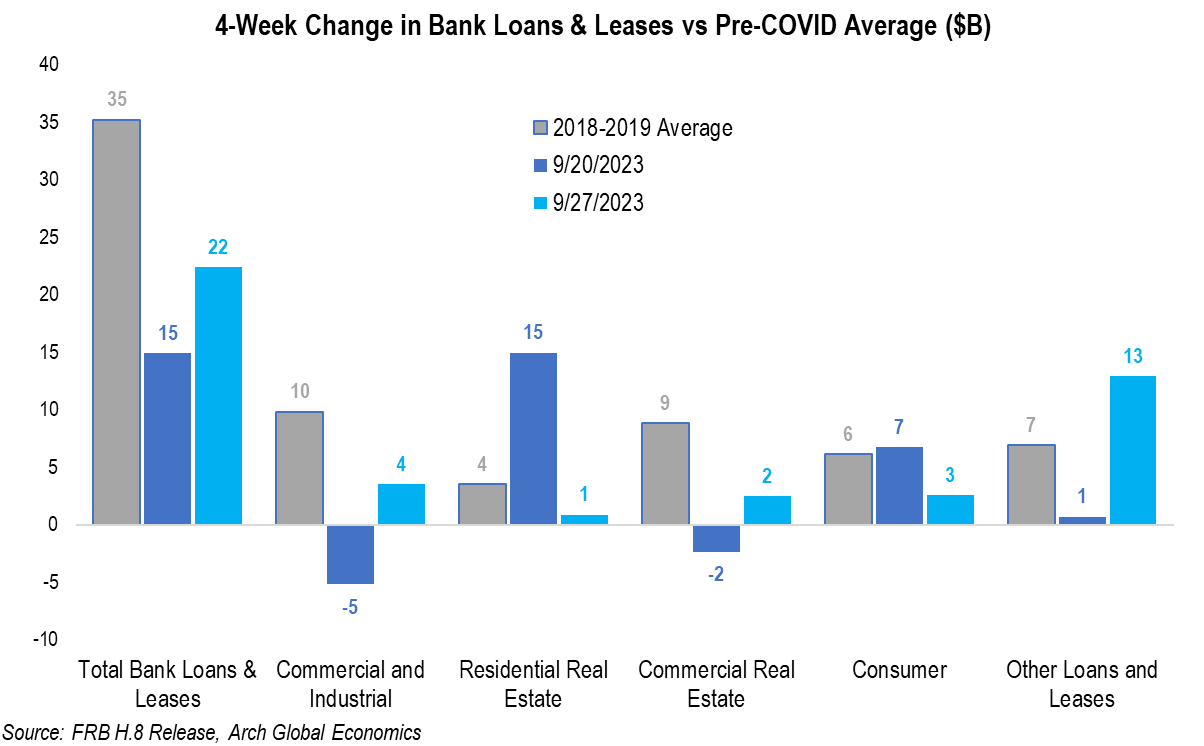

However, a closer look at the situation reveals some nuances:

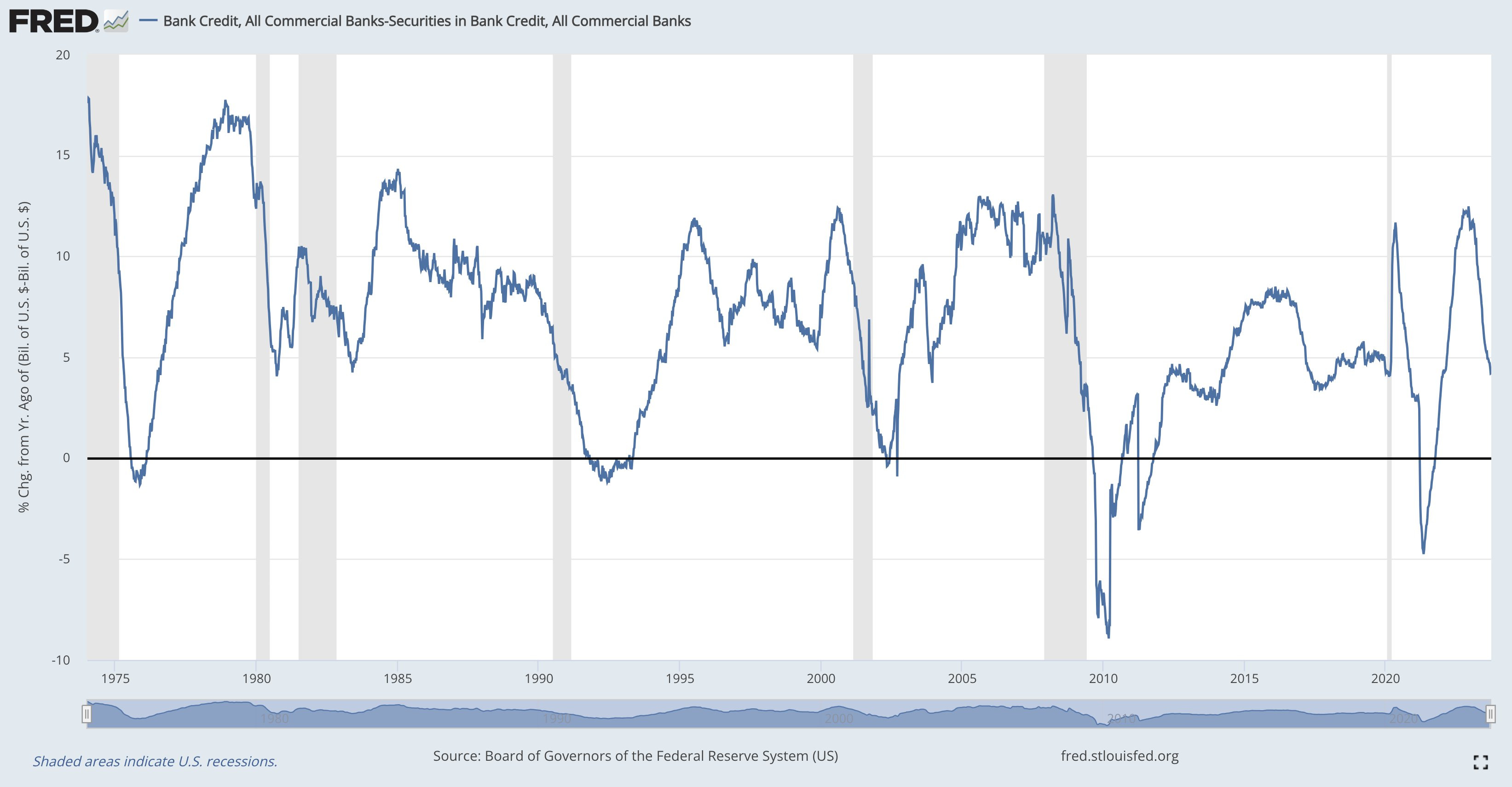

The contraction in credit is explained by the fall in SIBCs (Securities in Bank Credit). As these securities play a major role in the calculation of bank credit, their loss of value is one of the main reasons for the current contraction.

SIBCs include bank assets such as Treasury bills and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS).

Why has the value of these SIBCs fallen?

Rising interest rates are at the root of this decline. The value of MBSs is falling in the same way as other bonds:

If we ignore these SIBCs, there is no contraction in bank credit.

Banks have suffered unrealized losses, but have not yet restricted lending. Loans granted are below the pre-pandemic average, without giving rise to any major concerns for the time being:

Even if the credit supply is slowing down, we are still a long way from the situation experienced during the Covid crisis:

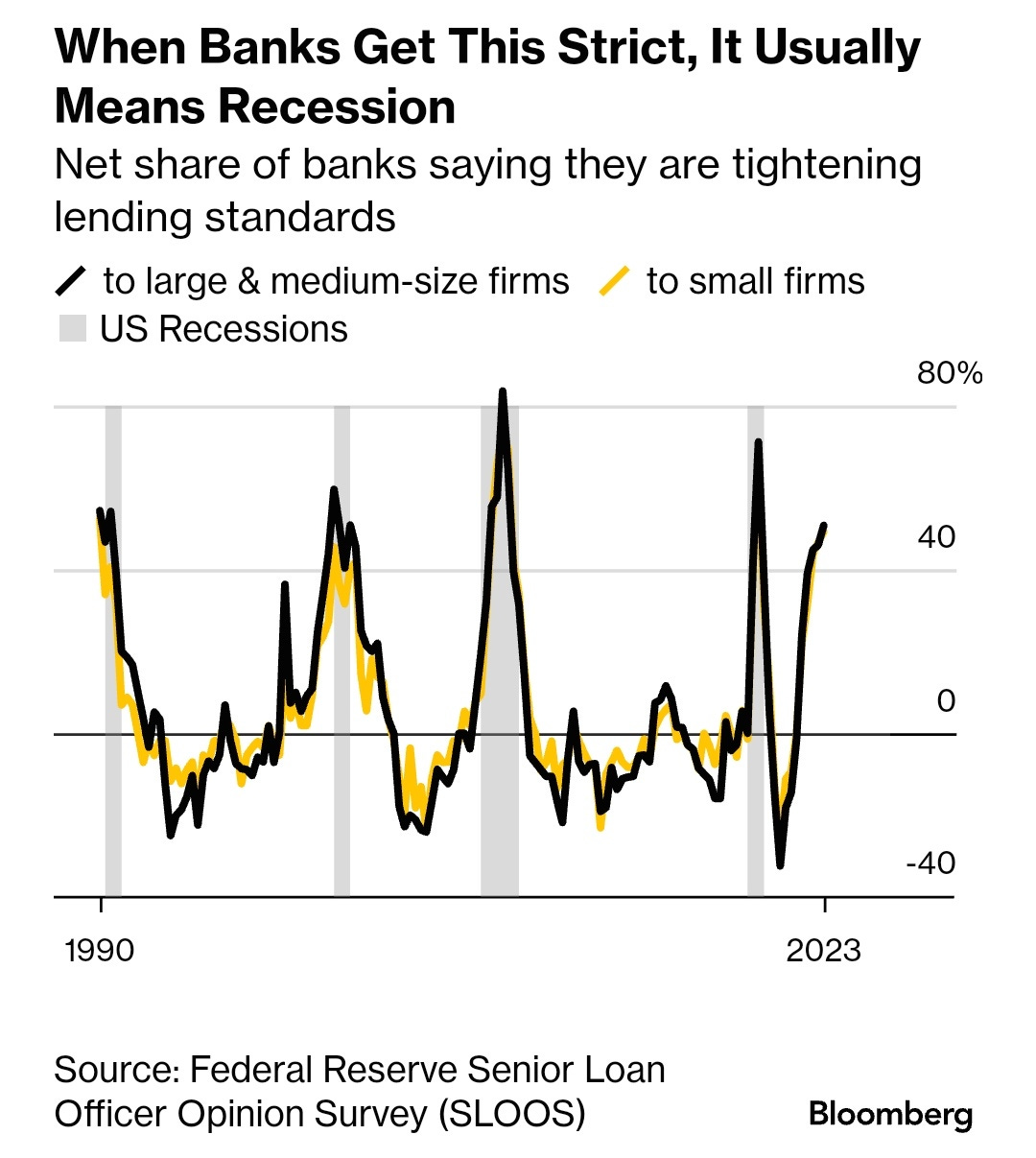

Unfortunately, the new conditions demanded by banks could well turn the current downturn into a real contraction:

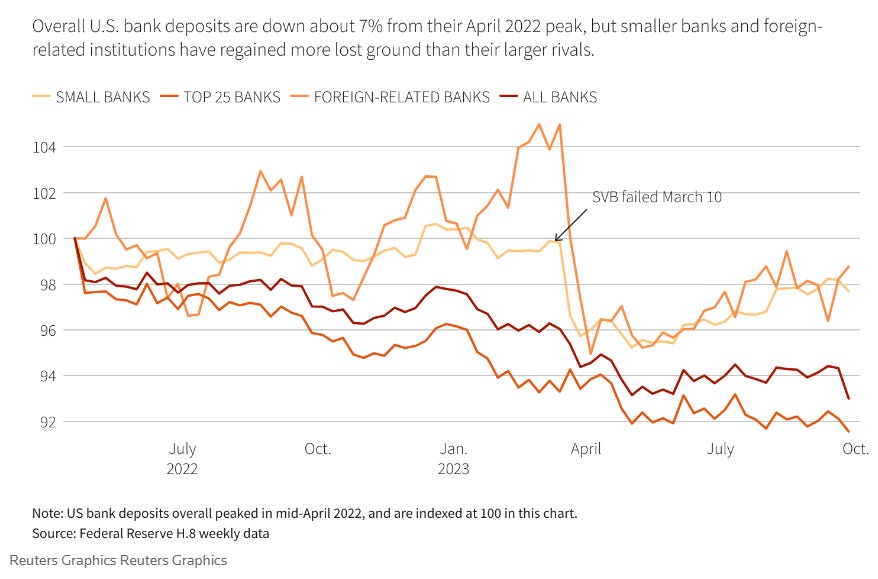

The increased complexity of credit conditions is also attributable to the increasingly complicated situation of banks, which have seen a flight of their depositors since 2022:

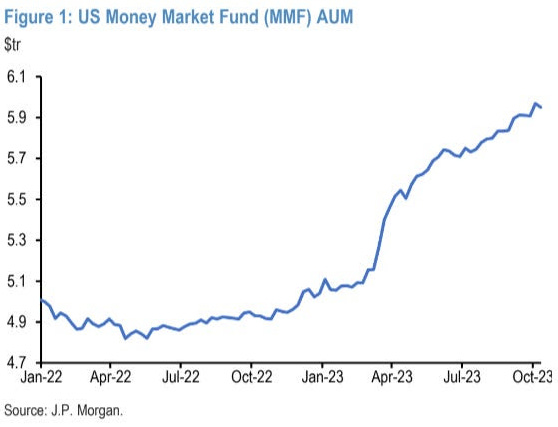

Americans are withdrawing their money from banks, as money market funds offer a better return on their savings. Money market funds are at a record high, approaching $6 trillion in assets under management:

The rescue plan put in place by the Fed when the SVB collapsed failed to stop the hemorrhaging in the US banking sector.

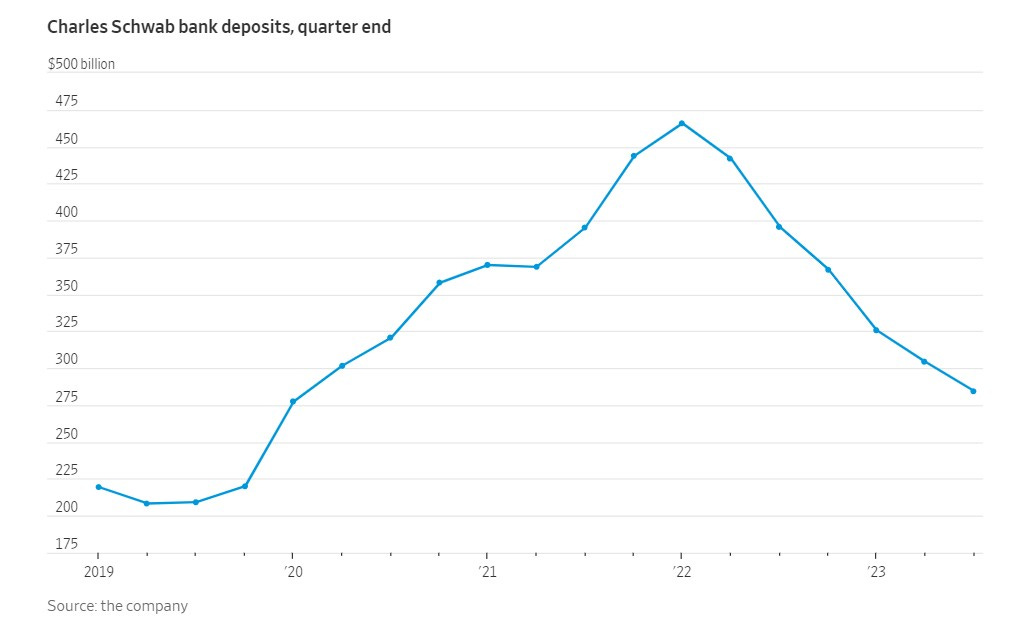

Charles Schwab's latest data confirms that this loss of deposits is not just affecting regional banks.

Since 2022, deposits at Charles Schwab have fallen from $475 billion to $275 billion:

The decline in the deposit base should logically have a direct effect on the bank's new lending restrictions.

Analysts tracking this reduction in deposits are sounding the alarm: in a fractional system, logically, the smaller the deposit base, the smaller the supply of loans. This reasoning was correct when we still had a real fractional banking system, i.e. before 2008. Since the last financial crisis, the Fed has changed the rules of the game, and banks have started charging interest on excess reserves. The deposit multiplier has not existed since 2008.

In other words, concluding that the erosion of deposits represents a systemic risk for banks is no longer very relevant since the Fed turned the tables with its numerous rescue plans.

The real systemic danger lies in credit activity itself. We're not yet in negative territory, but the situation can only logically deteriorate.

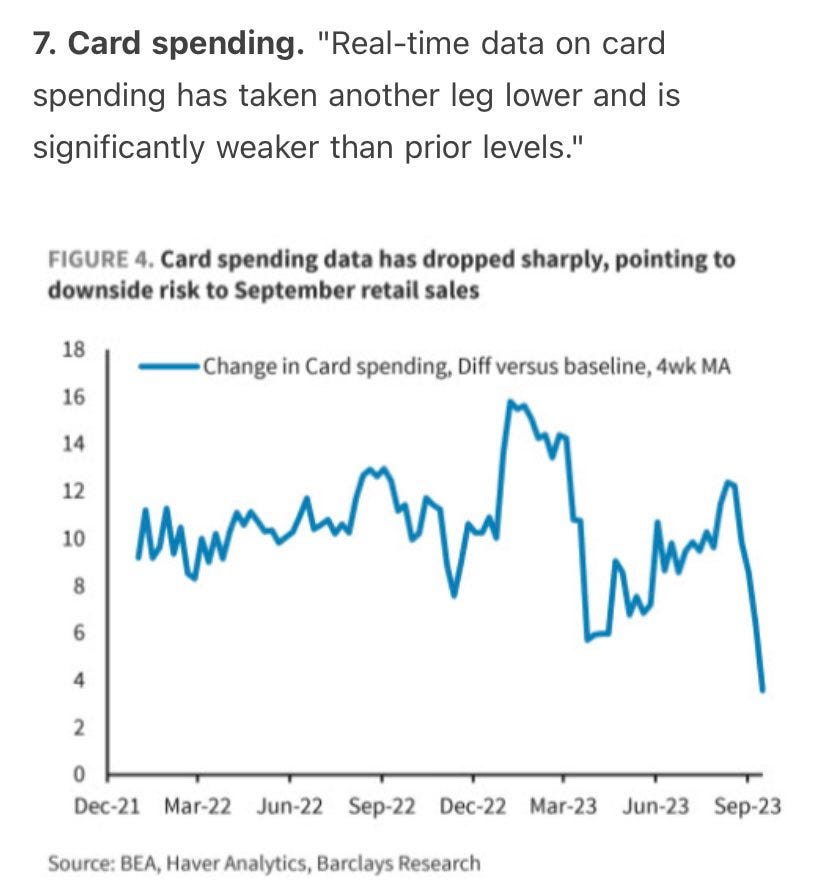

Naturally, the most fragile sector, consumer credit, is likely to be the first to suffer. Current consumer spending on credit cards has already fallen sharply in recent weeks:

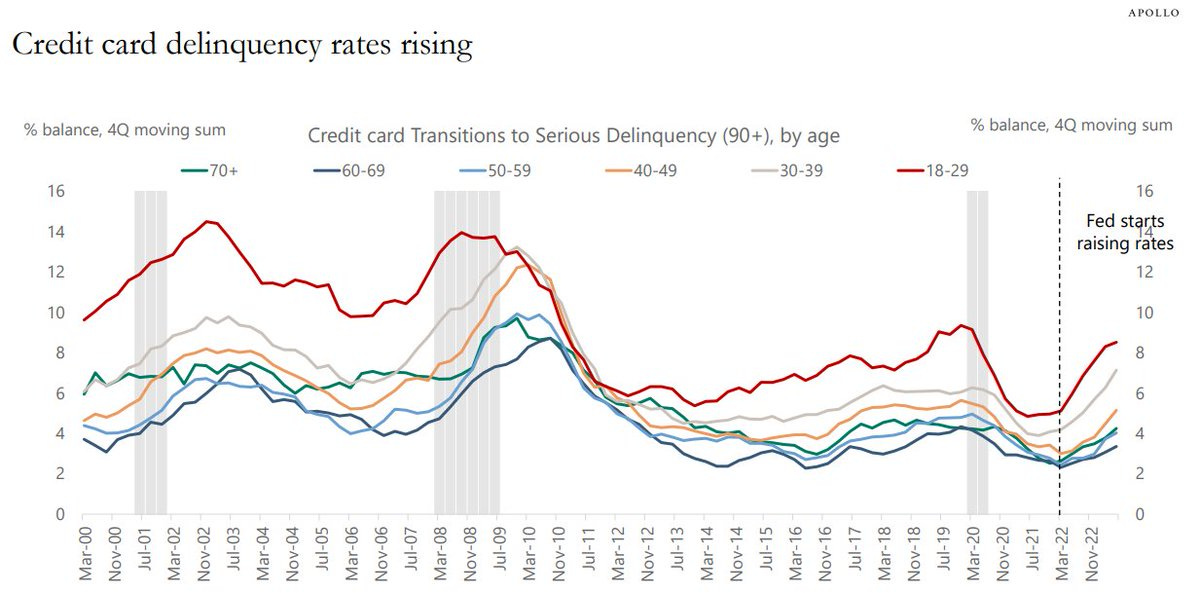

Credit card delinquencies are now accelerating in all age categories:

Defaults among 30-39 year-olds are increasing at the same rate as during the last financial crisis.

In the event of a more severe credit crunch, the risk of recession in the US would increase significantly.

The risk of a credit crunch increases as interest rates continue to rise: the higher interest rates rise, the more banks slow down new borrowing, and the more consumers are squeezed.

The US 10-year yield has risen back above 4.8%:

The price of gold should correct in this context of rising rates, but the tense geopolitical situation and the avalanche of upcoming Treasury auctions are keeping the yellow metal above $1,900:

A magnificent "morning star" pattern has just formed on the gold chart, providing a bullish signal.

It's been six years since we've seen such a reversal pattern in gold. The last "morning star" was in December 2017, at the $1,125 support level, a level that was never tested again thereafter.

Let's look at what happened then:

This bullish signal is undoubtedly behind the short squeeze on gold that has taken place in recent sessions. It remains to be seen whether rising rates will once again attract bearish speculators to these levels. It's hard to go short on gold at the moment! The indicators (real rates, dollar) that worked until 2022 are no longer as reliable as they used to be...

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.