On September 6, 2024, I wrote: "The United States Plunges Into Stagflation". Then, on March 7, I issued a new alert with an article entitled: "Stagflation Risks Worsening in Europe and the United States". At the time, the US economy was showing signs of slowing, with industry in decline, consumption at half-mast, and prices rising again. The cycle of defaults was already underway...

The Federal Reserve has just confirmed this: by revising its growth forecasts downwards, its unemployment expectations upwards, and by admitting persistent underlying inflation, the institution is now acknowledging a stagflationary future for the US economy.

The Fed anticipates more moderate growth in the years ahead, lowering its GDP forecasts to 1.4% for 2025 (from 1.7% previously) and 1.6% for 2026 (from 1.8%). At the same time, the unemployment rate is revised upwards, from 4.4% to 4.5% in 2025, while projections for 2026 and 2027 confirm a gradual deterioration in the job market.

In addition, core PCE inflation — a key indicator for the Fed — is expected to remain higher than previously forecast. It is now projected at 3.1% in 2025, compared with 2.8% previously, with levels also raised for 2026 and 2027. These adjustments confirm that the disinflation process will be slower and more uncertain than anticipated.

Finally, the Fed is forecasting a key rate of 3.6% in 2026, compared with 3.4% previously — a sign that it intends to maintain a restrictive monetary policy over an extended period to combat stiffer inflation. This cocktail of sluggish growth, rising unemployment and persistent inflation corresponds to the typical pattern of stagflation, seriously complicating the equation for monetary authorities.

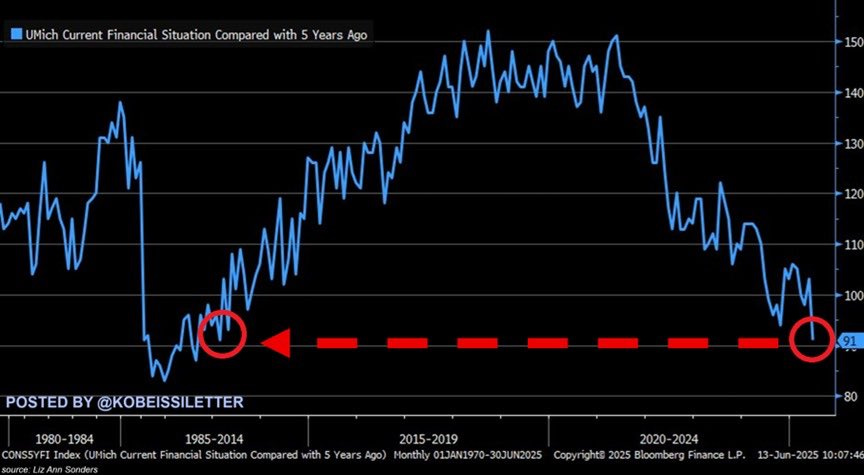

Back from the States, it's clear: the bottleneck facing American consumers is real, almost palpable on a daily basis. The debate is no longer so much about future inflation, but about the well-entrenched effects of the inflationary wave of recent years. This rise in prices has left deep scars. Even in the middle class, many people can no longer get by. Prices have risen above tolerable levels in relation to incomes, despite the fact that many people have several jobs. This structural imbalance is fuelling widespread pessimism: the consumer confidence index has fallen to its lowest levels since the 2008 crisis.

In June, US consumer sentiment regarding their personal financial situation fell to a twelve-year low of just 91 points. This decline is all the more striking given that in four years, the index has lost almost 60 points — a drop of around 39%. Consumer sentiment is now at a level comparable to that seen during the 2008 financial crisis, revealing deep and widespread concern among the population.

This deterioration in sentiment is due to a combination of factors: persistent price rises in recent years have severely eroded purchasing power, while the job market is showing signs of running out of steam. Many Americans now feel less financially comfortable than they did five years ago, despite sometimes rising incomes. The cost of living — particularly for food, housing and healthcare — is weighing heavily on household budgets. This growing pressure is fuelling a long-lasting malaise and accentuating the feeling of economic insecurity, even among those who still have a job.

However, the current situation is very different from that of the 2008 financial crisis. Back then, the main source of anxiety was the fear of losing one's job. Today, Americans are already feeling overwhelmed, even before considering their job security. What's eating away at them is the exorbitant cost of living, and the feeling of being trapped in a system that leaves them no room for manoeuvre. Working is no longer enough: no matter how hard you try, you just can't keep up. It's no longer just a question of economic crisis, but of profound psychological exhaustion — a feeling of dispossession in the face of a reality that seems to elude them completely.

Paradoxically, this stalemate remains a positive factor for gold. In a stagflationary environment — marked by sluggish growth, persistent inflation and growing consumer unease — the yellow metal is once again playing its role as a safe-haven asset. As traditional assets such as bonds lose their protective function in portfolios, gold becomes the natural alternative to guard against erosion of purchasing power, monetary instability and growing mistrust of current economic policies. This context automatically reinforces structural demand for the precious metal.

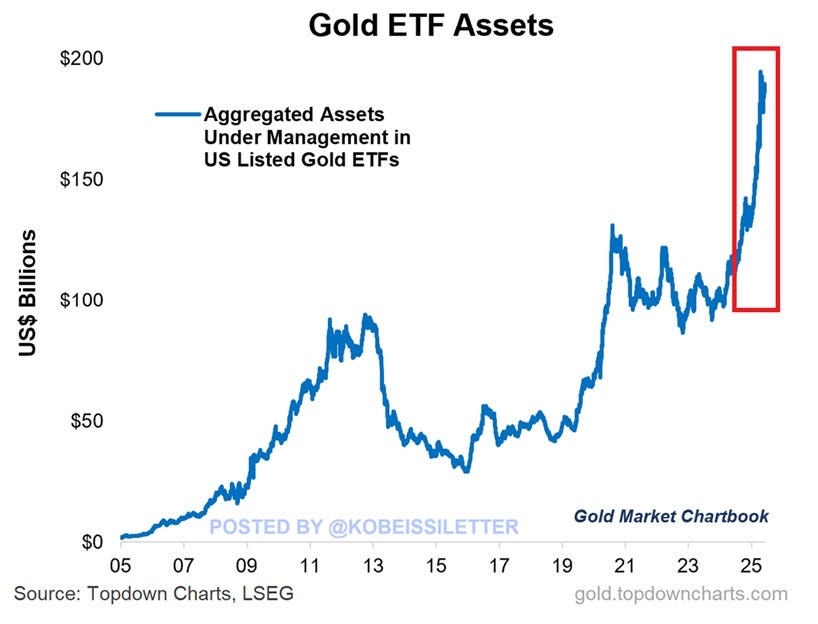

This week marks a historic milestone for the gold market: gold-backed ETFs in the United States have exceeded $190 billion for the first time. In just two years, the total value of assets held in these funds has jumped by around $100 billion, illustrating investors' growing appetite for the yellow metal.

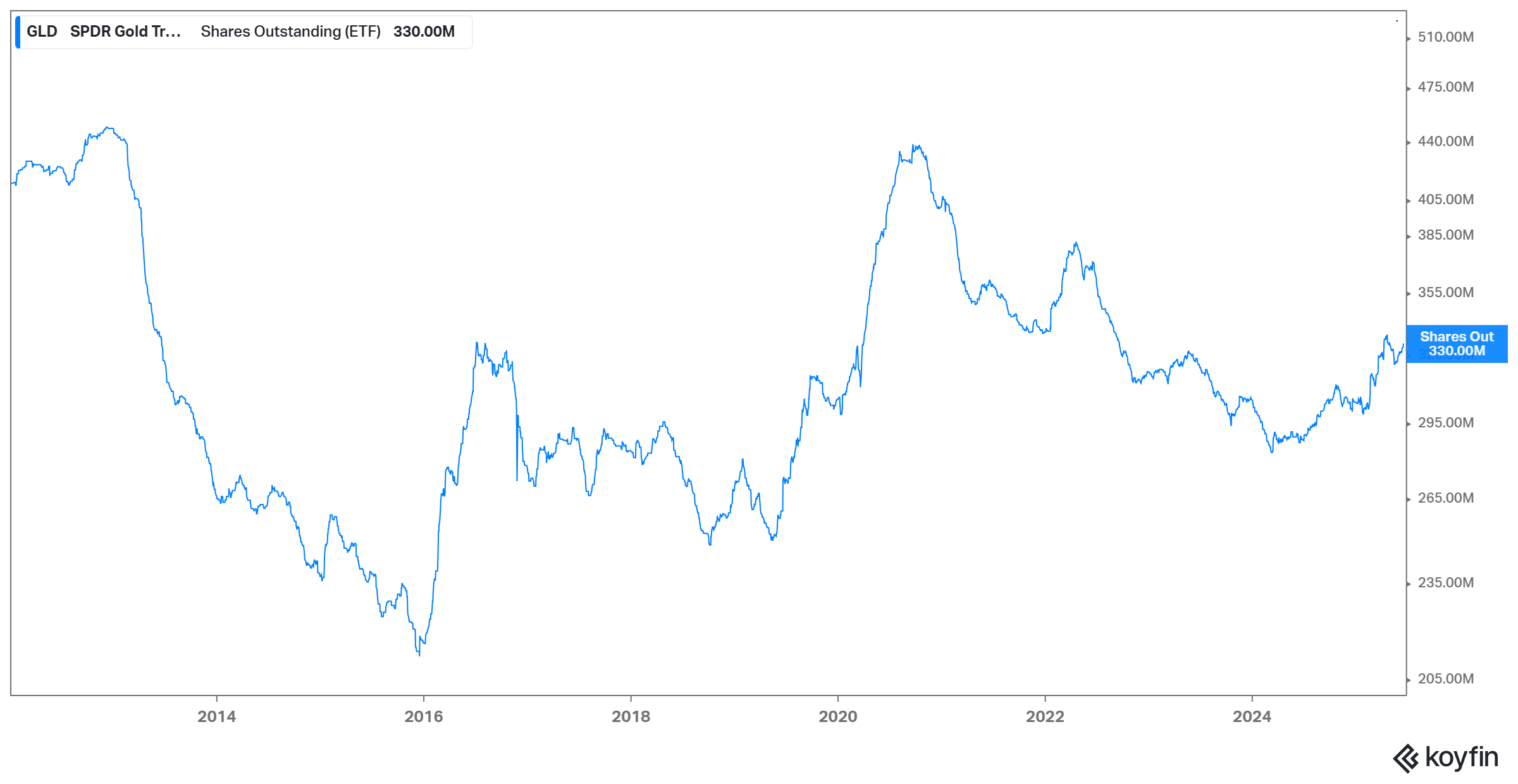

The most emblematic fund in this category, the SPDR Gold Trust (symbol: GLD), also passed a symbolic milestone: its assets under management exceeded the $100 billion mark for the first time. This spectacular increase reflects an underlying trend — a gold rush fuelled by a climate of economic and geopolitical uncertainty.

Although the dollar value of the $GLD fund's assets under management now exceeds $100 billion, this figure mainly reflects the appreciation of the gold price, and not a massive inflow of new physical gold. In fact, the actual quantity of gold held by GLD — 941.93 tons — remains almost 25% below its peak in August 2020, when it exceeded 1,250 tons.

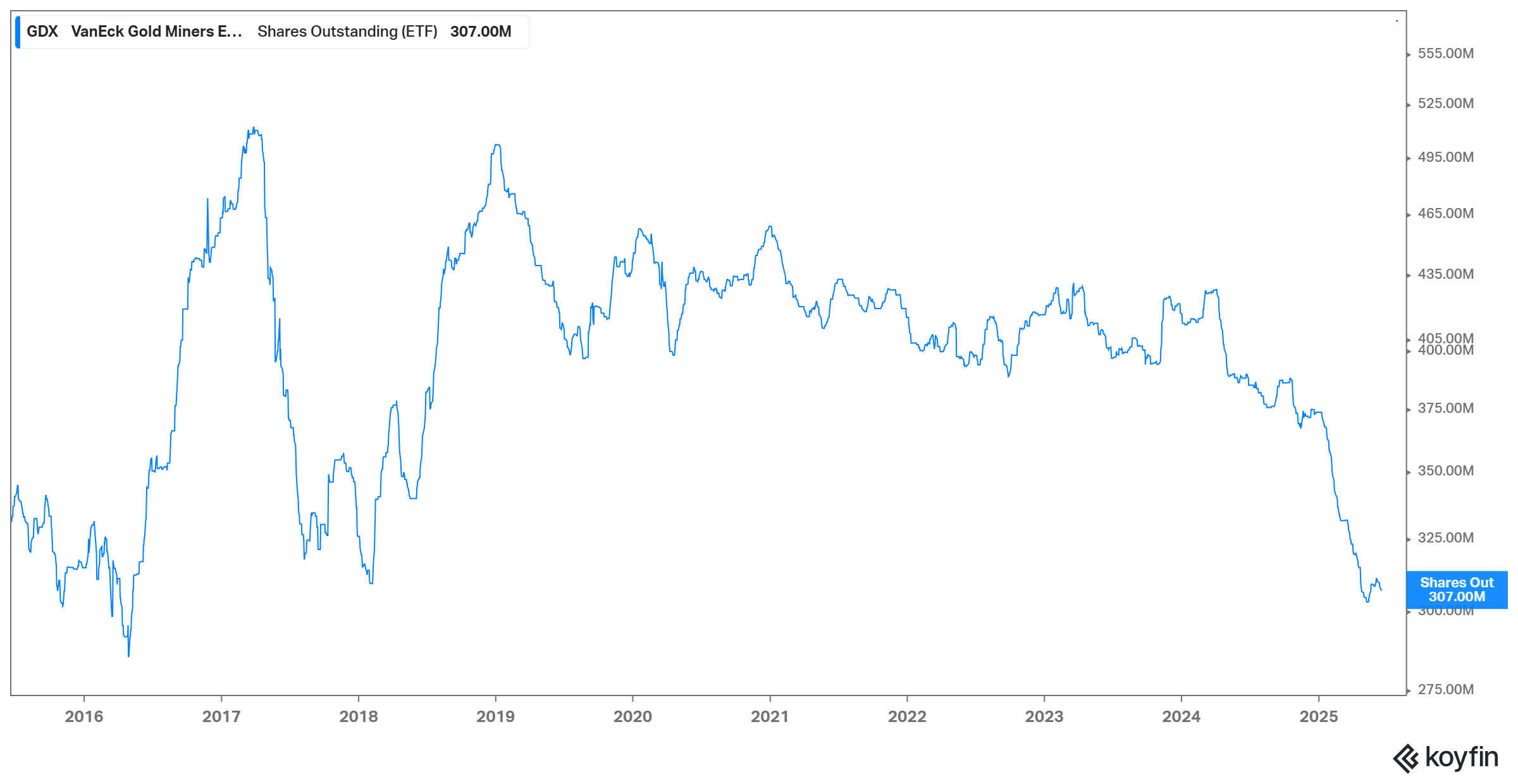

In other words, massive institutional flows into gold-backed ETFs have yet to return. The increase in total value is mainly driven by the rise in the gold price, not by an accumulation of physical metal. Despite a favorable environment for gold, most major investors have not yet fully returned to the asset class. This suggests a significant catch-up potential if a wave of buying really gets underway — particularly in the event of worsening economic or geopolitical instability. Catch-up potential for gold mining companies is even more spectacular than for physical gold itself. In fact, while the price of the yellow metal has returned to its all-time highs, and the assets under management of ETFs such as $GLD reflect this recovery, mining ETFs — in particular GDX, which groups together the sector's large caps — are still lagging far behind.

Assets under management in GDX are still close to their lows, a far cry from the peaks reached in 2020 or even 2011. This reflects investors' persistent disaffection with mining companies, despite a clear improvement in their fundamentals: rising margins with gold prices above $2,300 per ounce, massive deleveraging, strong growth in free cash flow (FCF) and historically high dividend levels.

In other words, miners have not yet benefited from the appetite for gold seen among central banks and private investors. This historical decorrelation between the price of gold and the valuation of producers creates an asymmetrical opportunity: as soon as flows return to this segment, the readjustment could be severe. This makes miners a lever on the metal, still under-utilized today, and a strategic target for investors seeking performance in a stagflationary environment.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.