The bond market remains under pressure.

Japan has just held another auction of its 30-year sovereign bonds (JGB), with a yield of 2.941%, up sharply on the previous 2.414%.

Japanese 30-year yields have now reached an all-time high, surpassing their 2008 level. But what is most worrying is the speed of this surge.

The yield curve of the Japanese 40-year bonds is even more impressive: the rise is dizzying, reflecting a sudden rejection of extreme duration and a loss of confidence in the long-term sustainability of Japanese public debt.

Long-term Japanese bond yields have doubled over the past two years.

The Japanese sovereign debt market is exploding before our very eyes.

The US market has not been spared either: the 30-year yield is once again flirting with 5%, the 20-year has exceeded 5%, while the 10-year continues its rapid rise, a sign of investors' growing distrust of duration risk and fiscal uncertainty.

The new budget bill proposed to the House of Representatives is highly expansionary in nature. It does more than simply extend the TCJA (Tax Cuts and Jobs Act), the major tax reform adopted under the Trump administration in 2017, which had notably lowered taxes massively for businesses and households. This project clearly worsens the budget outlook, with an estimated slippage of $2.5 trillion compared with forecasts drawn up a few weeks earlier! Even in a context of solid economic growth, it would put the United States on a trajectory of public deficits exceeding 8% of GDP. Initial ambitions for fiscal austerity were abandoned in favor of politically popular short-term measures, such as accelerated 100% depreciation on real estate investments. As for the spending cuts announced for the future, they mainly serve to mask the reality of a rapidly expanding deficit, the resolution of which is left to future generations.

This is a political U-turn and investors are starting to realize that this headlong rush is weakening the entire financial system.

Yields are now back to where they were at the end of 2018, when Trump announced a 90-day truce on tariffs under pressure from the bond markets.

When the bond market, and in particular that of US sovereign bonds (Treasuries), becomes unstable or loses investor confidence, it's not just bad news for financial portfolios: it's a crack in the very foundations of the global financial architecture. Government bonds are not just another asset. They are the foundation on which a whole series of essential mechanisms rest, which could be called the four pillars of financial stability:

- Collateral chains

- Risk parity strategies

- Pension fund models

- Dollar-anchored exchange rate regimes

Let's try to explain these four pillars in detail.

Let's start with collateral chains. In certain specialized markets, notably the interbank and short-term financing (“Repo”) markets, financial players borrow by depositing securities as collateral. Government bonds such as Treasuries, which are considered “risk-free”, are the most prized collateral. But when their price falls sharply - because interest rates rise, for example, or investors lose confidence in the sustainability of US debt - these bonds lose their value as collateral. In practical terms, this means that borrowers have to deposit more collateral to obtain the same amount, triggering margin calls, liquidity withdrawals and a freeze on short-term financing. This is exactly what we began to see on the US Repo market in early 2023, and more dramatically in September 2019, when the Fed had to intervene in an emergency to inject hundreds of billions of dollars into a dried-up market.

Is a new Repo market crisis still possible today?

The risk of this crucial market suddenly grinding to a halt remains, even if it is now much better regulated than it was in 2019. That year, the US Repo market experienced extreme tension, almost overnight. Interest rates on very short-term secured loans soared above 10%, while the Fed's key rate was below 2%. The market literally ran out of liquidity, revealing just how fragile the financial infrastructure was in the face of a simple imbalance between cash supply and demand.

This crisis took everyone by surprise, as it was not caused by a geopolitical event or a banking collapse, but by a combination of technical factors. That day, companies had to pay their taxes, suddenly withdrawing hundreds of billions of dollars from the banking system. At the same time, the major banks were refusing to lend out their excess liquidity, as they had reached their balance sheet limits. What's more, the US Treasury had just issued a large quantity of bonds, absorbing even more liquidity without it being recycled.

Since the crisis, the Federal Reserve has taken structural measures to prevent such a situation from recurring. In particular, it has set up a permanent window called the Standing Repo Facility. This mechanism enables major banks and certain financial players to obtain immediate liquidity against government bonds, without having to go through the market. This acts as an automatic safety valve in times of stress. The Fed also has another tool at its disposal: the Reverse Repo Facility. This facility regulates excess liquidity in the system, but can also release hundreds of billions of dollars very quickly if necessary. As of May 2025, more than $500 billion is still parked in this facility, constituting a substantial mobilizable reserve.

However, these measures are not enough to eliminate all risk. The Treasuries market has grown spectacularly and now exceeds $34 trillion in outstandings, challenging banks' ability to absorb these issues. At the same time, the banking system is becoming increasingly asymmetrical: a few large banks concentrate the majority of reserves, while smaller banks or non-banks (such as hedge funds) have very limited access to liquidity. Yet it is often these marginal players who operate on the Repo market on a massive scale, notably via highly leveraged strategies such as basis trades.

In the event of an external crisis - such as a panic in the bond market, a crisis of confidence in US debt, or a major geopolitical event - even the current systems could be overwhelmed. The system remains vulnerable to chain reactions, especially if the Fed were to delay intervention or confidence were to suddenly disappear. Since 2019, it's not the nature of the risk that has changed, but the central bank's ability to frame it quickly. As long as the Fed remains vigilant and reactive, a crisis similar to 2019 can probably be avoided. But in a world of exploding debt and weakening liquidity, the system's resilience cannot rest forever on the agility of a single institution.

The second pillar to be weakened concerns so-called “risk parity” strategies, widely adopted by large institutional investors. The idea is to spread risk between equities and bonds, assuming that the two react differently to the economic environment: when equities fall, bonds rise, and vice versa. This model worked for almost forty years in a context of disinflation. But since 2022, this correlation has been reversed: both assets are falling at the same time, as inflation puts pressure on both corporate earnings and bond values. As a result, portfolios that are supposed to be balanced find themselves exposed to massive losses on all fronts.

In 2022, the "60/40” portfolios — made up of 60% equities and 40% bonds - long considered prudent, have recorded disastrous performances, among the worst since the 1930s. This shows that when bonds cease to play their stabilizing role, an entire generation of portfolio management is left without a compass.

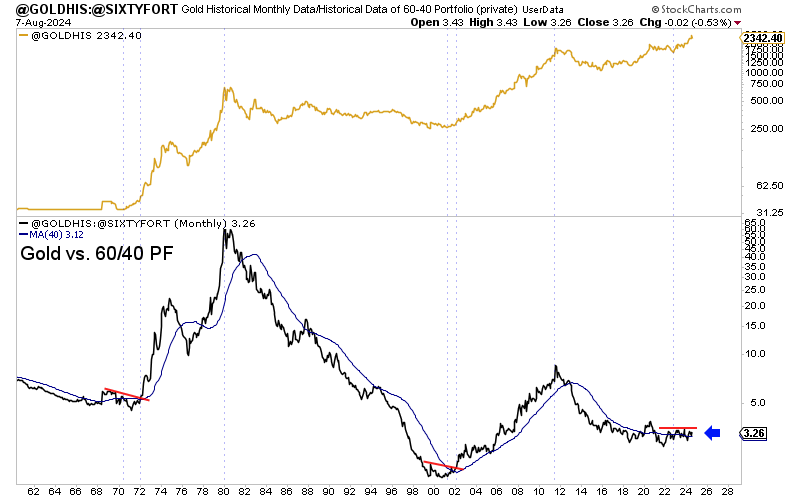

In my bulletin from August 28, 2024, I wrote:

"Since 1980, gold has never really managed to outperform a conventional portfolio composed of 60% bonds and 40% equities. The years 2000-2011 are an exception. Since Volcker's intervention in interest rates in 1980, gold has systematically underperformed this 60/40 investment strategy, which has enriched two generations of asset managers. Why invest in gold when such a simple, world-renowned strategy works so well?

Only when this chart breaks to the upside will gold become a must-have for Western investors. Gold will be favored provided it manages to outperform the classic strategy that has prevailed since 1980.”

In the same bulletin, I published this chart:

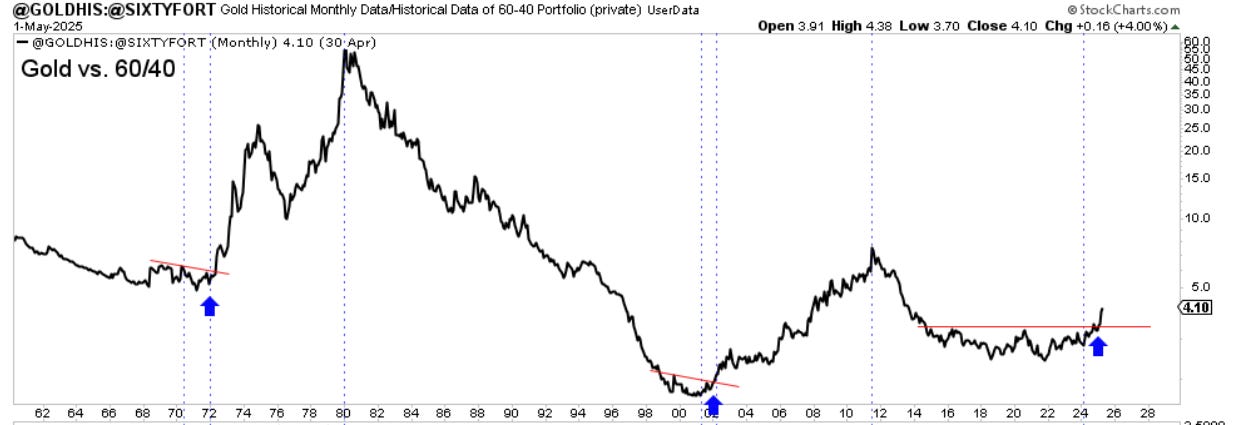

Nine months on, what do we see? The chart comparing gold to the 60/40 portfolio has broken through its resistance:

The price of gold is sending out the same signal today as it did in 1972 and 2001: that of a growing systemic risk, which 60/40 portfolio managers have yet to fully identify.

The third pillar at risk concerns pension funds, whose long-term commitments are based on relatively stable and predictable return assumptions. These funds generally hold a large proportion of bonds in their portfolios, as these provide them with regular income to finance future pensions. However, when interest rates rise rapidly, not only does the value of the bonds in the portfolio fall, but future commitments become more expensive to meet in discounted terms. This can lead to dangerous imbalances. A striking example is the UK in September 2022, when the Truss government announced a budget plan with no credible funding. Yields on Gilts (British sovereign bonds) soared, undermining the stability of pension funds that used derivatives to hedge their liabilities. Taken by surprise, these funds had to sell their assets in a hurry, threatening to collapse the entire British bond market. The Bank of England was forced to intervene to avert a systemic disaster.

Finally, the fourth pillar concerns fixed exchange rate regimes, in particular those of countries that have pegged their currencies to the US dollar. This choice is based on a crucial condition: the stability and predictability of the Treasuries market, since the foreign exchange reserves used to defend the peg are largely denominated in US bonds. If these bonds lose credibility or value, the central banks of these countries have to draw on their reserves to support their currencies, at the risk of rapidly exhausting them. The case of Hong Kong is emblematic: the city has maintained a strict peg to the dollar for decades, but recent pressure from rising US interest rates has forced its central bank to intervene more and more frequently to defend parity. This type of tension can degenerate into a currency crisis, as we have seen in the past in Thailand (1997), Argentina (2002), or more recently in Egypt and Nigeria, whose peg regimes eventually collapsed under the pressure of dollar debt and global tightening.

In short, a crisis in the US bond market is not an isolated or technical event. It touches the very foundations of the global financial system, disrupting collateral, investment strategies, the solvency of pension systems and international monetary equilibrium. If one of these pillars breaks down, the others tremble. And if all are weakened simultaneously, the whole edifice risks breaking up. This is why a collapse in the Treasuries market is not just another “rate shock”: it is potentially the signal for a global systemic crisis.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.