When we compare the performance of different investments (gold, real estate, stocks, bonds, commodities, etc.), we often forget an essential element: are we talking about a homogeneous asset or a category? It's not the same thing: "You can't compare apples and oranges", as the saying goes.

Gold is gold everywhere on the planet, it's perfectly homogeneous, so its price has real meaning. "Real estate" means nothing. You buy this or that property, and each one is unique. The same goes for bonds (which country? which company? which maturity? which currency?), commodities (each with its own logic) and equities (this or that company).

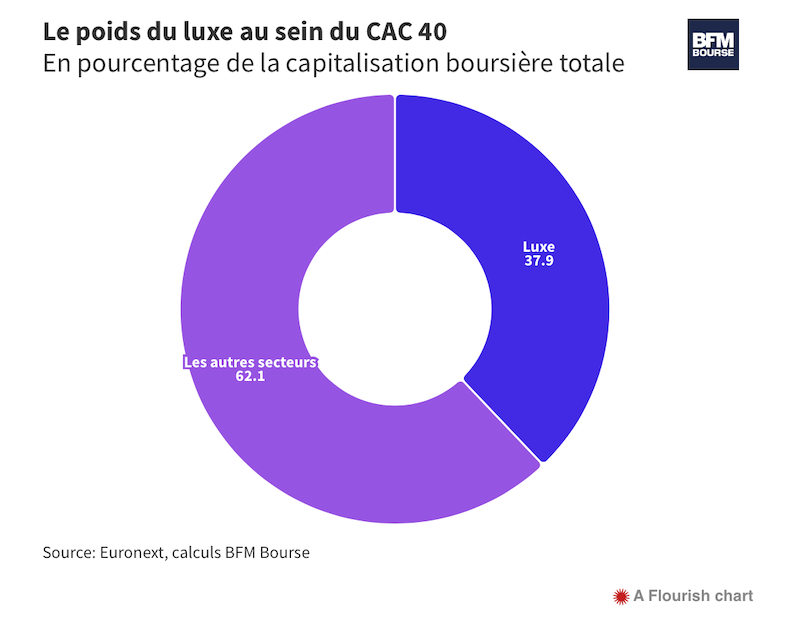

Let's take a look at the latter. Often contrasted with gold, stocks are said to yield higher returns, and are the best long-term asset. But what are we talking about? Most often, indexes. We forget that these are completely distorted by an optical effect known as weighting: the higher a stock price rises, the greater its weight in the index... which pushes the index up all the more. It's like a snake biting its own tail. In the end, the index is completely distorted, representing only the few best-performing companies. For example, luxury brands - just three companies (LVMH, Hermès, Kering) - account for almost 40% of the CAC40. (BFM Bourse) :

So you might as well buy LVMH, Hermès and Kering outright, but only if you did so a long time ago, when the luxury goods industry wasn't so glittering, which is quite a gamble. On the other hand, those who have bought Danone, Axa, BNP Paribas or Renault have not performed breathtakingly well, far from it.

The same applies to the Nasdaq: the five best-performing technology companies account for 43.6% of the index (Apple 12.07%; Nvidia 7.29%; Microsoft 12.8%; Amazon 6.91%; Tesla 4.46%), almost as much as the other 95 companies that make up the index! Tesla's recent fever pitch has pushed this figure up to 48%. Obviously, those who bought Apple when Steve Jobs took over the reins (1997) pulled off an exceptional coup, even though it was no longer a question of buying "stocks" but of making a very specific and, at the time, very risky bet. How many people have such flair? Warren Buffet and a few others... Nvidia is booming thanks to artificial intelligence, but will it last? Tesla's stock price is extremely volatile, and the Chinese competition is proving to be very sharp... Performance is not without risk.

Aware of the problem, Nasdaq is planning to reduce the weighting of these five companies from 43.6% to 38.5% on July 24. But this won't fundamentally change anything - our vision will still be distorted. The general idea will prevail that "stocks" are a great investment, when in reality they are just a few ultra-performing global companies that few investors had spotted in their early days.

You can also say "I'll buy the index", the CAC40 or the Nasdaq, in the form of an ETF, and wait. Of course, and that's the best thing to do, because you benefit from the weighting effect. You're no longer really buying equities, but an index that becomes very sensitive to a few companies. Diversification is almost non-existent, even though it is one of the basic principles of stock investing (Markowitz's portfolio theory), and the risk is therefore high. In short, all these factors need to be borne in mind when comparing different investments, and in the end, stocks don't really shine as brightly as they used to...

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.