As we saw last week, the fall of the bond markets has repercussions on the Treasury bill market. This decline is affecting these products in Europe, with consequences for life insurance contracts.

The question now is whether the sudden rise in rates will have an impact on the housing market. This article is devoted exclusively to the U.S. housing market.

In the U.S., the sharp rise in real estate rates has completely changed the borrowing capacity of first-time homebuyers. In just a few months, rates have risen from 2% to 7% for a 30-year rate, and the decision to raise them again this week could push these rates above 8% in the very short term.

The current rate hike is much faster than the one seen in 2007.

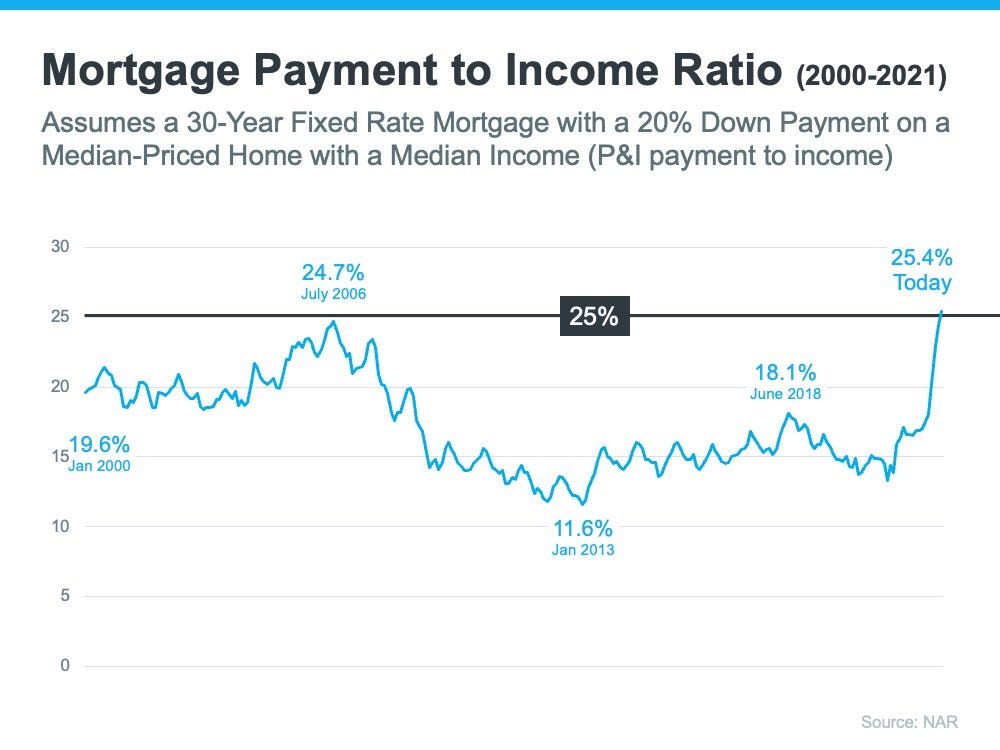

The cost of borrowing compared to the income of a first-time buyer is already at the same level as during the previous real estate crisis:

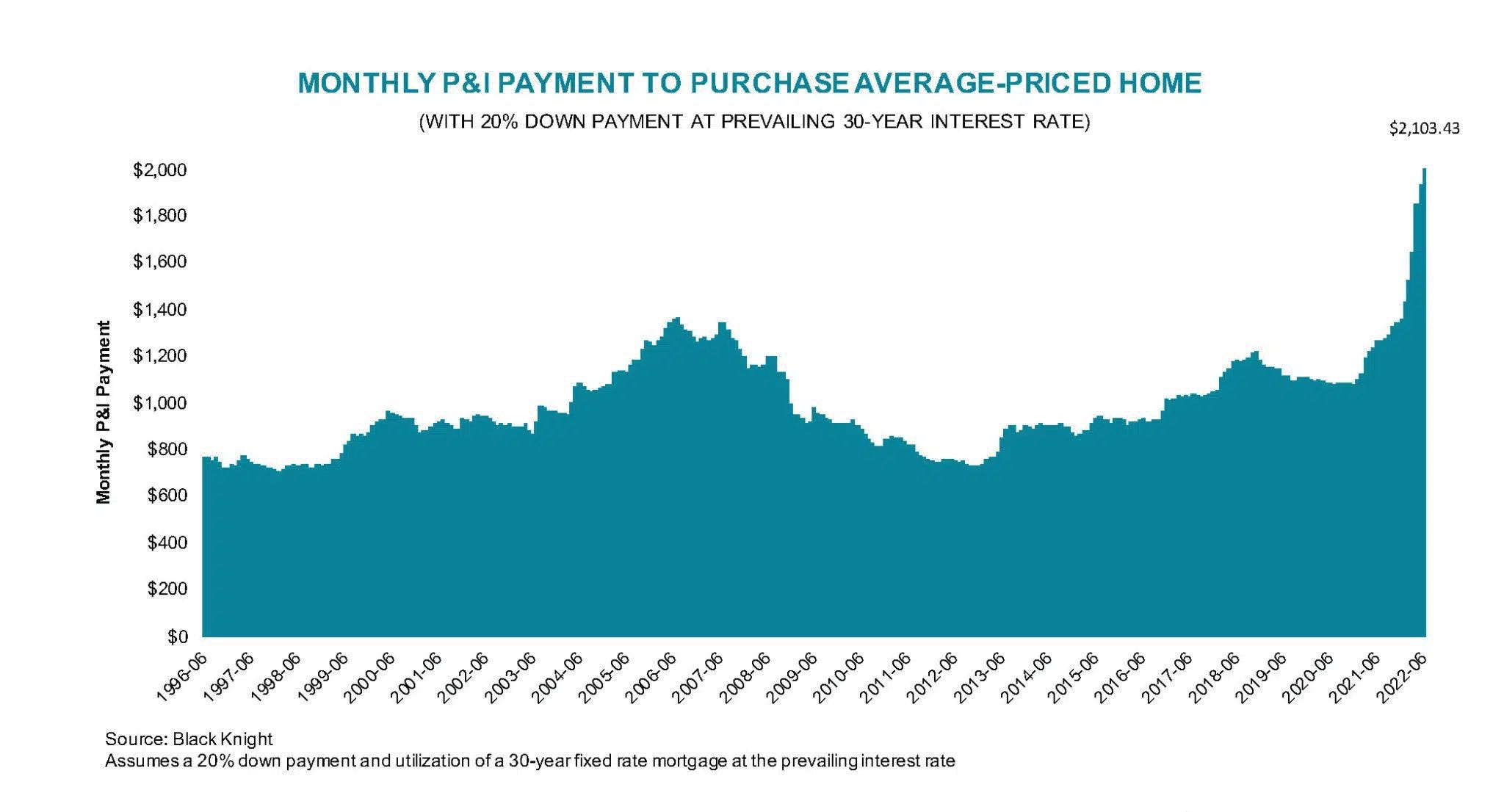

For a 20% down payment, the average monthly payment on a 30-year mortgage has already doubled in many parts of the United States in just a few months:

For example, to buy a home in Austin, Texas, it costs more than $3,000 per month (including $2,500 to cover interest from the first monthly payment), whereas with the same loan term and the same down payment it would cost only $1,100 in 2020 (the interest cost was only $600 at that time).

The violent rise in interest rates dramatically impacts the price level of a home that a household can afford. A household that could afford a $450,000 property a year ago can no longer afford a property that exceeds $300,000!

The consequences on transaction volumes are logically just as significant.

As in all highly leveraged markets, real estate prices are set by the next buyer's available margin level, i.e. his or her borrowing capacity. It is logical to see the market empty of potential buyers as this available margin capacity is reduced.

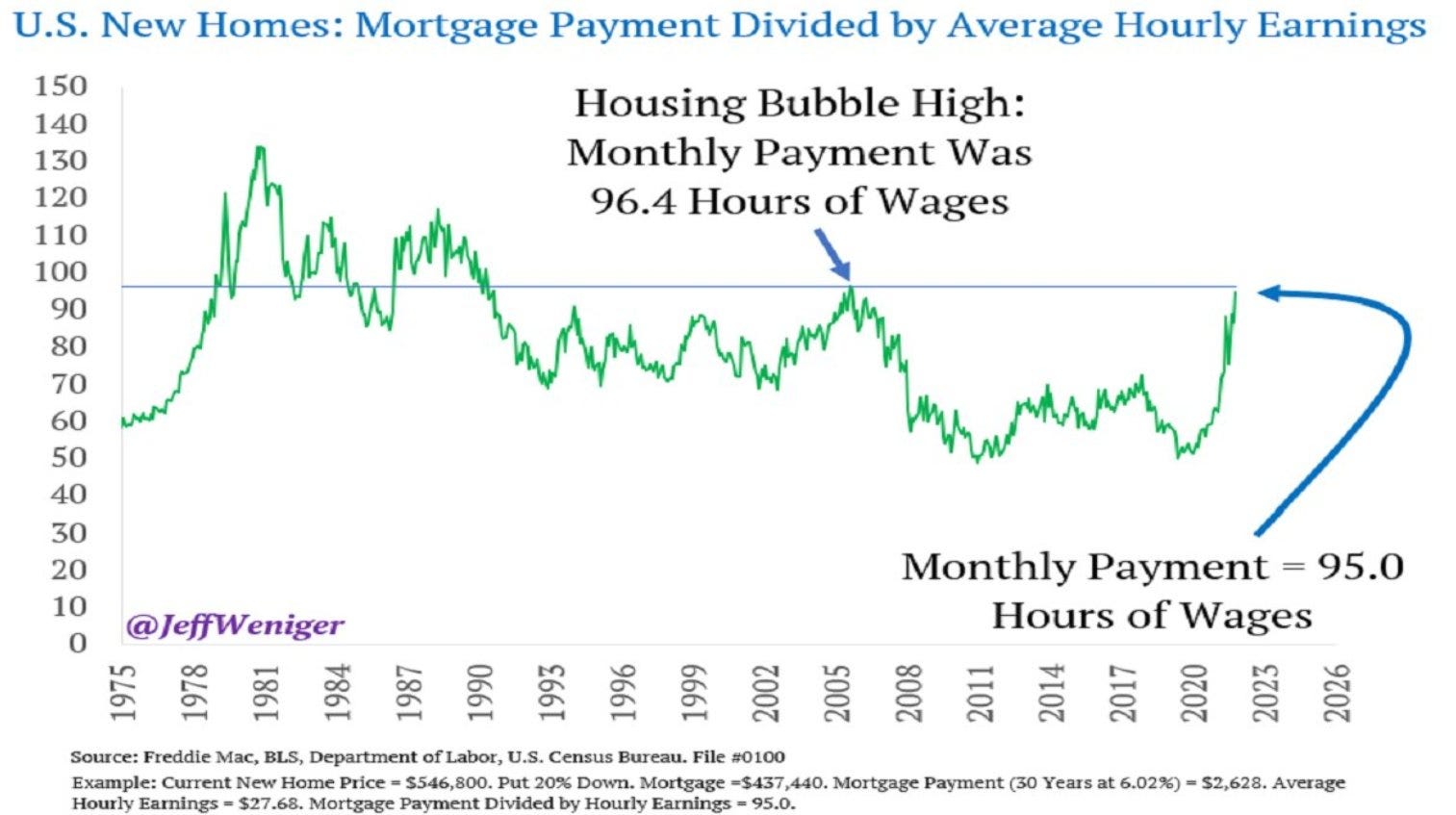

Analyst Jeff Weninger has even calculated that compared to 2020, it takes twice as many hours worked to meet an average new mortgage payment.

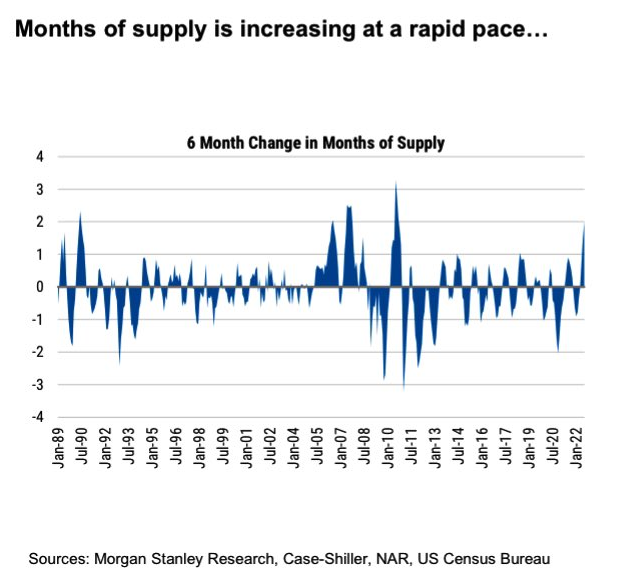

Under these conditions, cancellations of promises to sell are increasing significantly. The increase in unsold inventory is also rising at an alarming rate.

Mortgage application volume is down 64% from a year ago. The refinance index is down a dramatic 83.3%. These figures are consistent with the historic pace of interest rate increases.

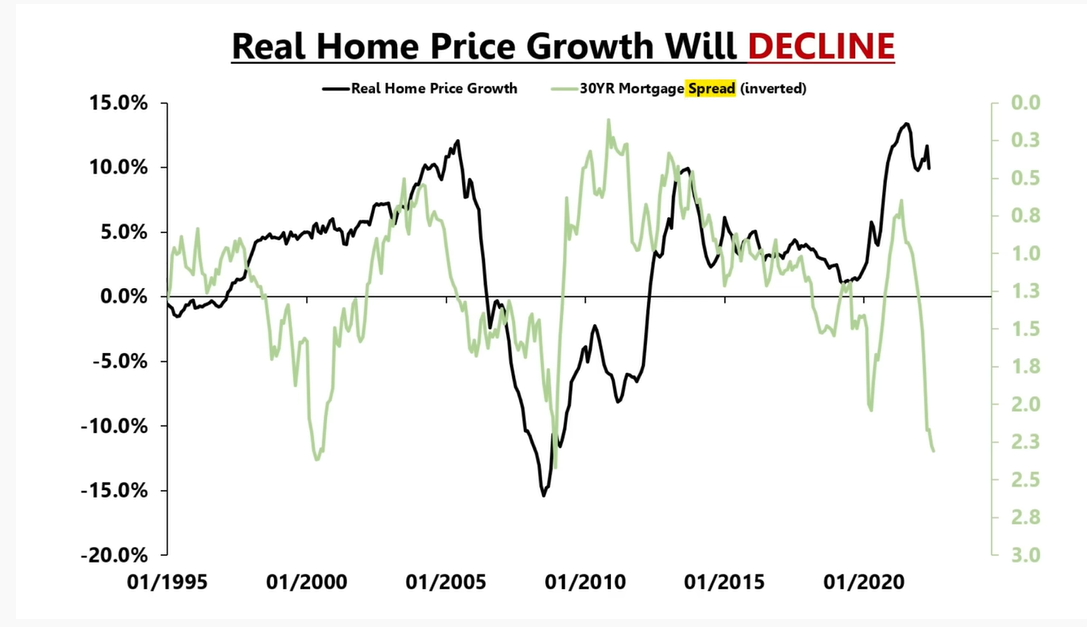

By abruptly raising rates, the Fed has brought real estate transactions in the U.S. to a screeching halt, but can we talk about a collapse in prices at this point? The decline in transaction volumes has not yet been reflected in prices. But if we look at what happened during the previous housing crisis, we see that the price decline occurred a few months after the sharp rise in rates:

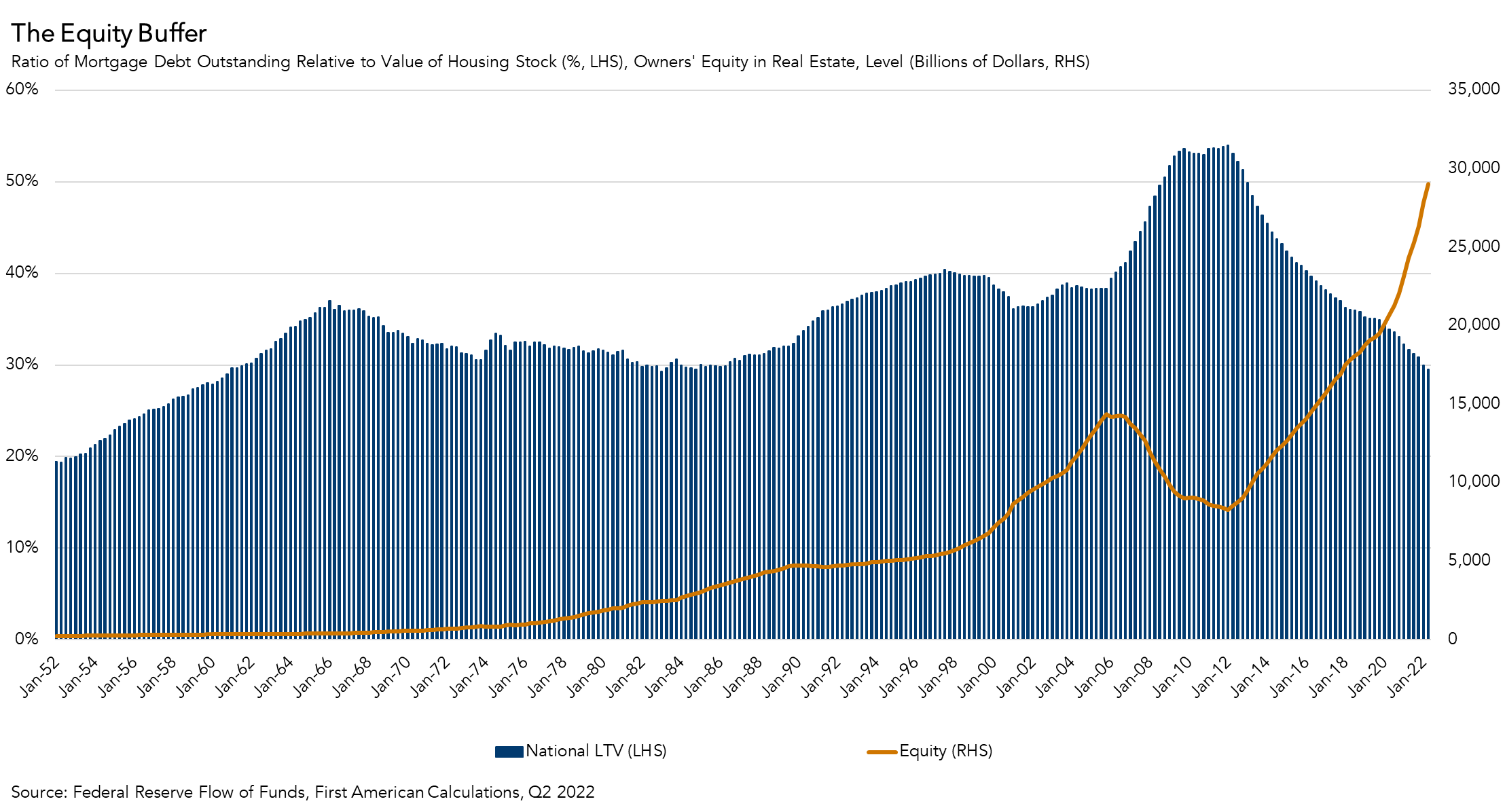

However, the conditions are not the same as in 2007. Toxic loans, the so-called subprime mortgages, were the main cause of the price decline during the last real estate crisis. There is nothing comparable today: recent buyers are not in the same fragile conditions as in 2007, loans are less toxic, and even if volumes are falling, there is no indication that households will be forced to sell in the short term. U.S. households own $41 trillion in real estate, with just over $12 trillion in debt and the remaining $29 trillion in equity. In the second quarter of 2022, the LTV (loan-to-value) was 29.5%, the lowest since 1983:

U.S. homeowners had an average of $320,000 of inflation-adjusted equity in their homes in the second quarter of 2022. An all-time high.

Even as they scramble to sell their properties at the top of the market, these homeowners don't have a knife to the throat like they did in 2007. They even have a shield built into the equity of their homes, which is far greater than during the last housing crisis.

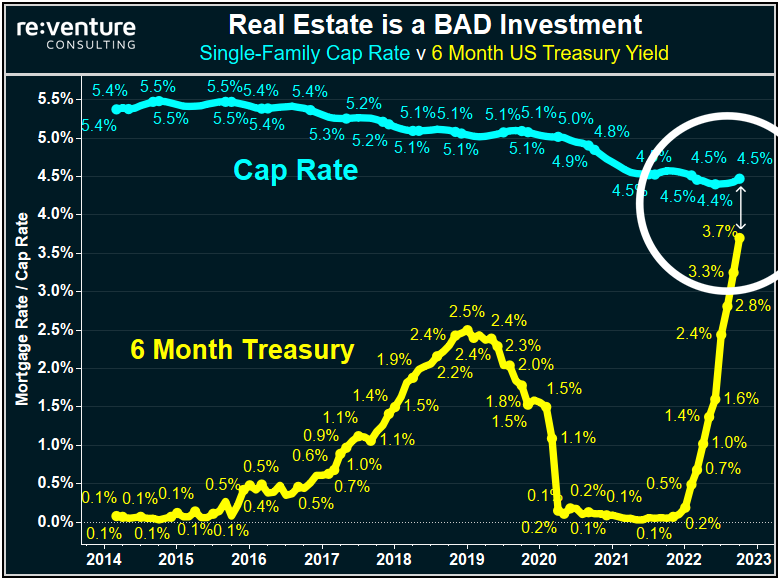

On the other hand, sales could come from institutional investors who have largely surfed on this last wave of real estate appreciation and who no longer have any interest in holding an investment of this type. The risk-free 6-month yields on Treasury bills are catching up with the average rate of return on a rental investment:

In other words, the risk of real estate investment will cause funds to slow down their purchases. But it is also likely that institutions will unload their assets, which they had intended to hold only during the bubble period.

Starwood Capital Group announced the sale of 3,000 previously acquired residential homes.

It is the sale by these institutions that is likely to trigger the price decline.

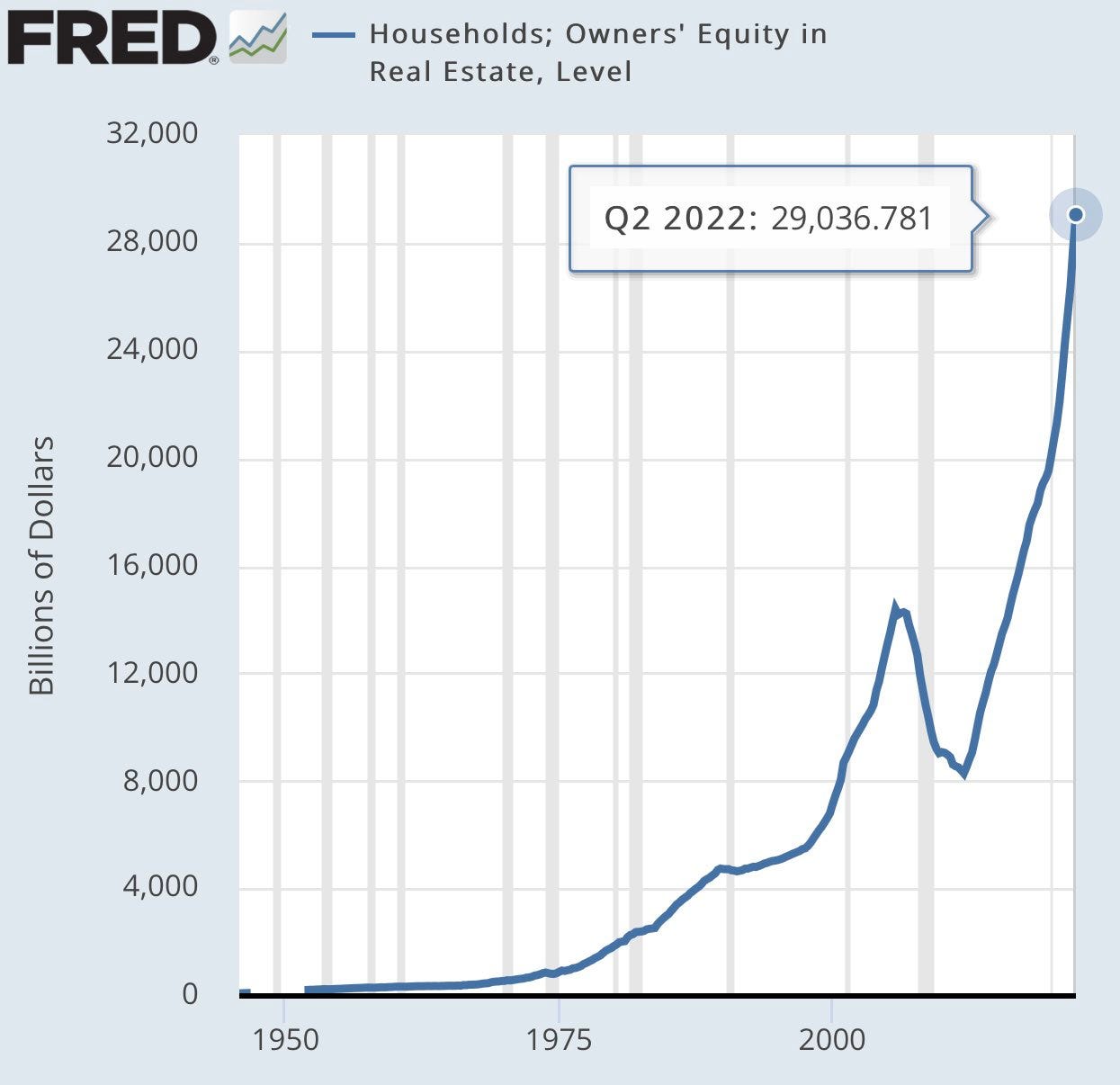

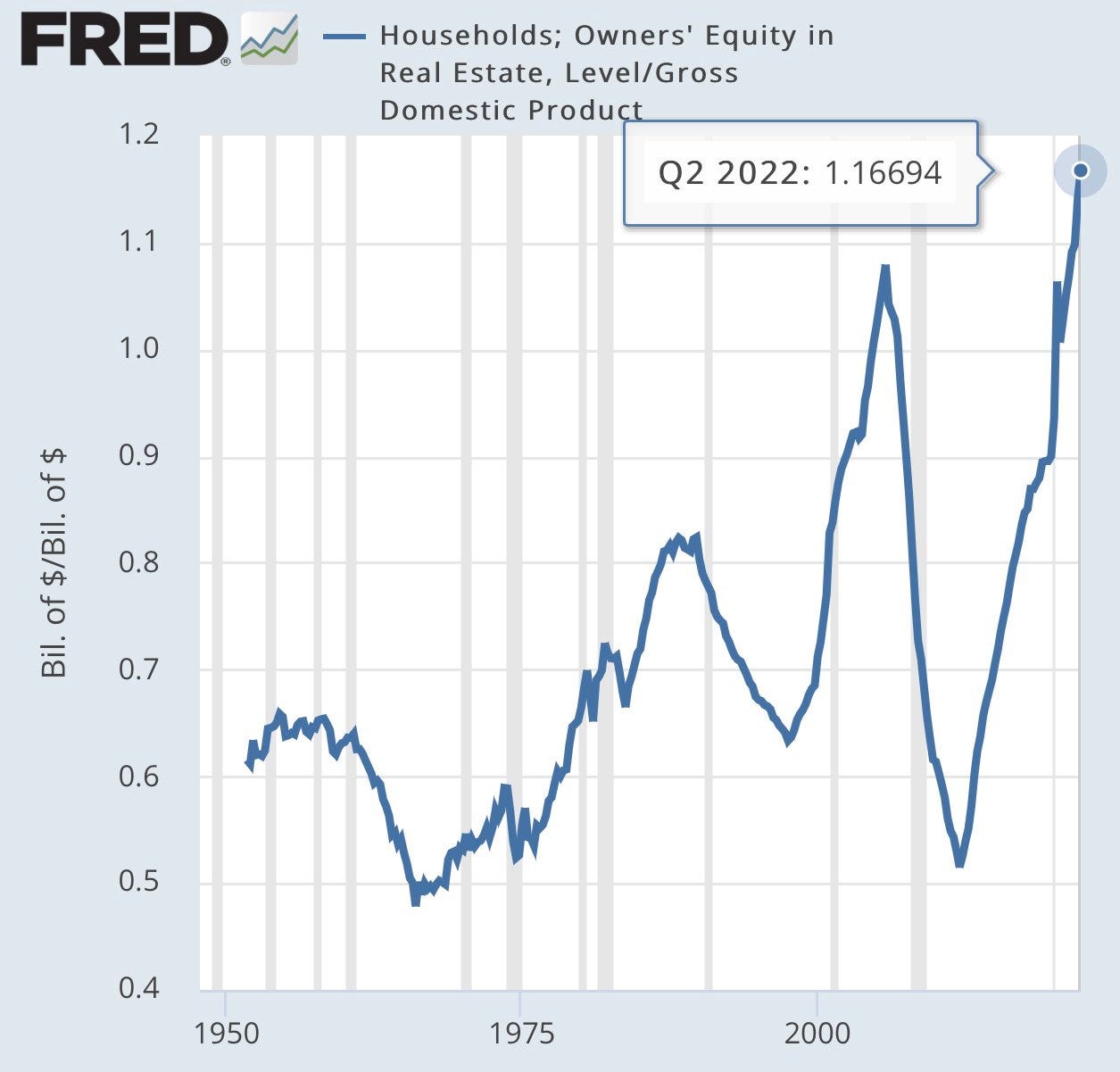

This decline would exacerbate the economic slowdown: the share of wealth held in real estate has never been so high in the United States:

Relative to GDP, this wealth represents an even greater level than during the last bubble in 2007:

When Paul Volcker initiated the sharp rise in rates in the 1980s, the wealth held in real estate was much less.

This time, by driving down real estate prices, the rate hike is likely to have a much more devastating wealth loss effect.

The Fed is looking at the temporary effects of a rate hike and thinks it can achieve a smooth slowdown in the economy.

It is ignoring the potential devastating effect of a housing bubble bursting even bigger than in 2007. The Fed's first mistake was to miss the start of inflation. We may now be witnessing the second mistake: in trying to create a useful recession to fight inflation, the US central bank is ignoring the unprecedented and irreversible impoverishment that the sudden rise in rates threatens to create.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.