Is gold still the foundation of our monetary system? This question is worth asking as central banks accumulate record quantities of the golden metal. In fact, a detailed study of central bank gold inventories reveals a certain consistency in the monetary strategy of most countries. Gold, with a certain degree of sensitivity, still appears to be the monetary "base of the base". The counterpart of "hard" money, the heart of the monetary engine.

Despite the end of the gold standard in 1971, and the explosion in the quantity of money in circulation, gold appears with disturbing constancy in the news and in the balance sheets of central banks. The eternal metal seems to make up for the shortcomings of contemporary money, in an age of inflation and geopolitical upheaval. We live in a monetary system that does not reveal its true nature, as if it were free of everything and above all free not to reveal its foundations.

Gold on central bank balance sheets

Since 2000, the value of the European Central Bank's balance sheet has risen from almost 800 billion euros to almost 7 trillion euros in 2023. The value of the ECB's balance sheet has thus risen from 11% of eurozone GDP in 2000, to over 48% in 2023. Simple monetary dynamics or genuine institutional inflation? The absence of a gold standard has encouraged the free and sustained expansion of the quantity of money in circulation.

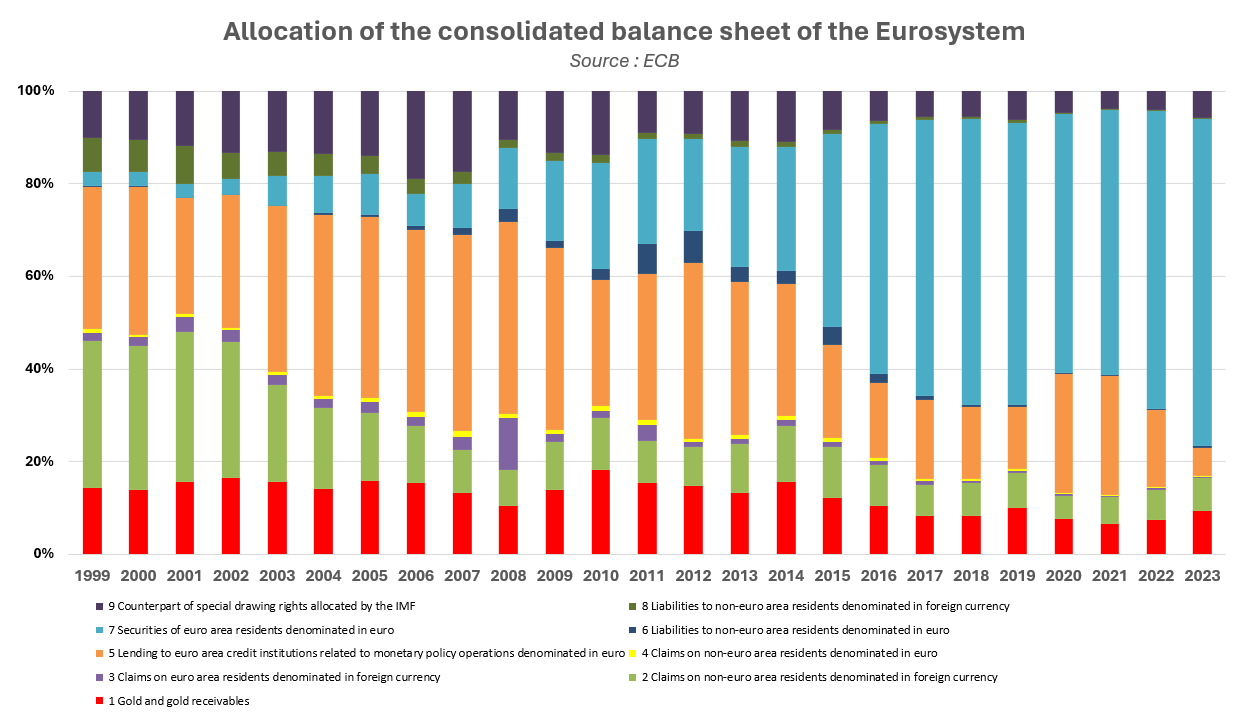

Despite this considerable monetary expansion, and the growing role of central banks, it is remarkable that the proportion of gold in central bank balance sheets has remained unchanged. Between 2000 and 2024, the share of gold in the ECB's balance sheet fluctuated between 6.5% and 18%. The chart above shows the share of different assets in the ECB's balance sheet over time. We can clearly see the persistence and stability of the red curve, i.e. gold's share of the ECB's balance sheet. Gold is remarkably rated "A1", i.e. the leading asset on the central bank's balance sheet!

While the proportion of gold in the ECB's balance sheet has remained broadly unchanged, despite the significant increase in the balance sheet since 2000, other assets have been squeezed out. For example, the proportion of debt owed to the rest of the world in euros or foreign currencies has plummeted. Conversely, the proportion of financial securities composed mainly of government bonds has risen from less than 3% of the balance sheet in 2000 to over 70% in 2023. Assuming a stable balance sheet, the ECB holds 23 times more financial securities than in 2000...

This structural change indicates a new reality: the ECB has become a creditor of its own economy rather than of the outside world! It's always better to be a creditor to the outside world than to your own economy... But despite these radical changes, central banks have chosen to keep gold on their balance sheets.

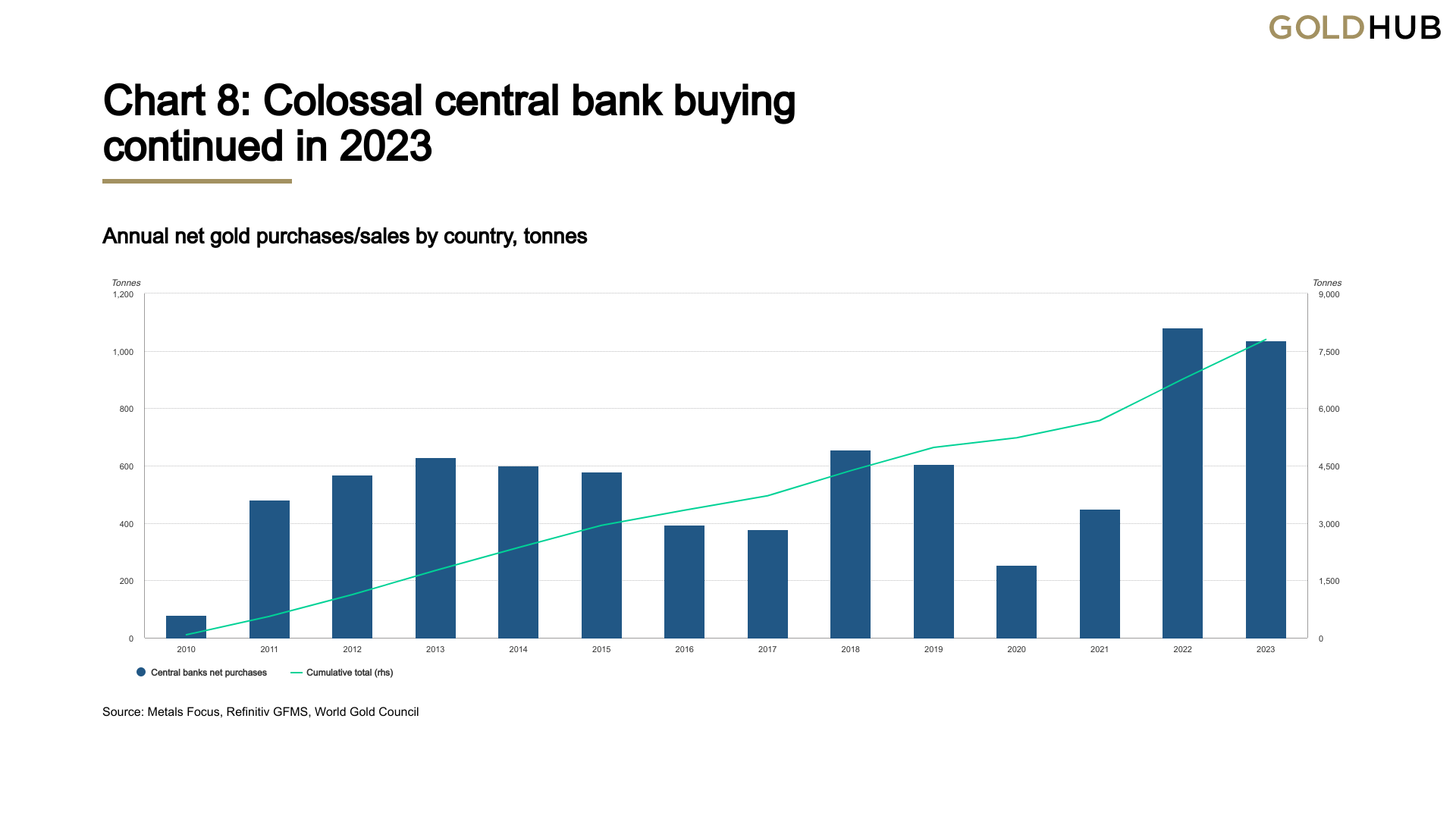

The massive accumulation of gold in recent years

We also note that in 2023, central bank demand accounted for almost 20% of all physical gold market demand. Since 2010, central banks have accumulated nearly 8,000 tons of gold worldwide, almost as much as the entire US gold stockpile, or around 5% of all foreign exchange reserves by value in 2023. Gold is therefore an integral part of global monetary, financial and geopolitical strategies.

Gold and foreign exchange reserves

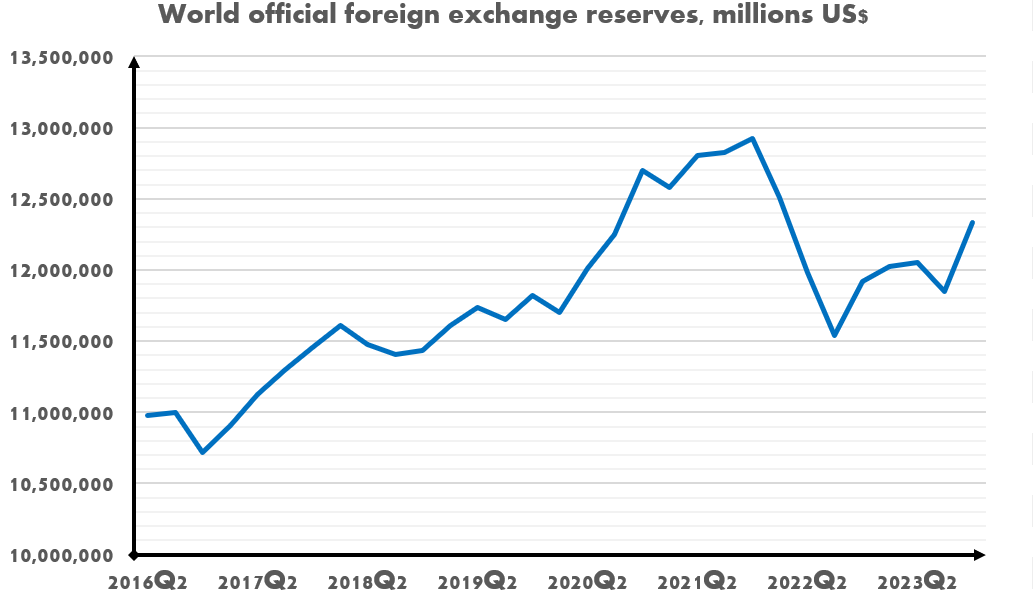

Managing foreign exchange reserves is another key task for central banks. Foreign exchange reserves enable countries to stabilize their currencies, hedge their international bonds, foster investor confidence, etc. Consequently, if central bank foreign exchange reserves increase, and the share of gold in central bank balance sheets remains constant, then central banks will drive gold purchases.

The chart below shows the evolution of foreign exchange reserves since 2016. We can clearly see that the increase in foreign exchange reserves between 2016 and 2020 was broadly symmetrical with the price of gold. Similarly, the peak in 2012 and the major trough in 2016 in the value of global foreign exchange reserves were synchronized with the price of gold.

The greater the volume of trade, or the greater the devaluation of the national currency, the greater the need for foreign exchange reserves. In the presence of excessive inflation, the resulting devaluation of the currency leads to a greater need for foreign exchange reserves. But in the face of a tense geopolitical situation, and to ensure strong stability for reserves, physical gold often appears to be the best solution. This is one of the reasons why Turkey has bought large quantities of gold in recent years. Similarly, China buys gold on a massive scale, mainly because the proportion of gold in its foreign exchange reserves is relatively low.

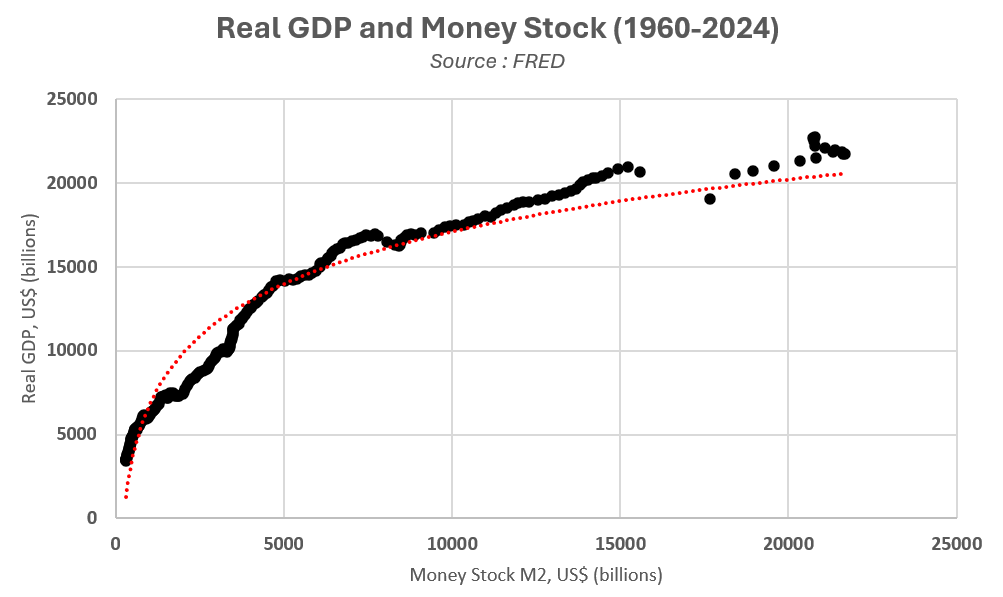

Sustained growth in money supply increases risk

A fundamental dynamic of the current monetary system is the increasing expansion of the money supply to generate the same unit of growth. The quantity of money needed to generate the same euro (or dollar) of growth is becoming ever greater. The chart below shows the value of GDP for the United States as a function of the quantity of money in circulation. We observe a logarithmic relationship between the two variables, meaning that more and more money is needed to generate one additional unit of production. This relationship clearly reflects the fact that the current monetary system is inefficient at actually generating sustainable growth, without a significant increase in debt and in the weight of financial institutions (thereby increasing the risk of systemic bankruptcy...).

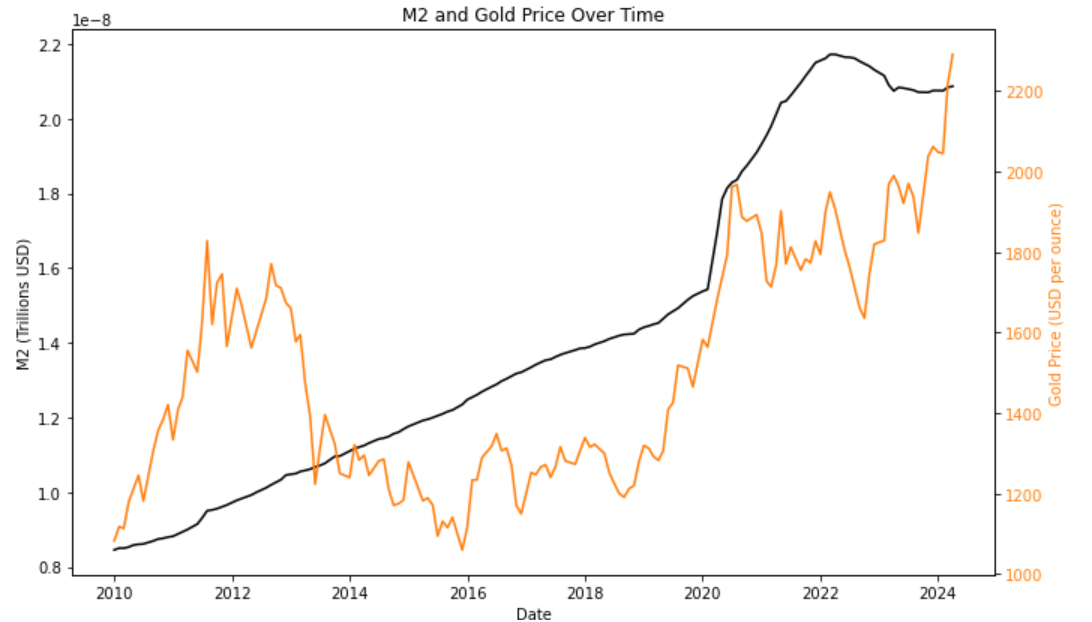

Furthermore, the growing expansion of the money supply can be attributed in part to the expansion of central banks' balance sheets. Central banks are increasing their monetary support to the economy. However, money creation in itself can be explained by more favorable credit conditions and growing indebtedness on the part of economic players. It is therefore clear that an increase in the quantity of money leads at the very least to inflation in financial assets. Note the high correlation between the S&P 500 and money supply over the long term. It would seem coherent to observe a link between money supply and the price of gold.

Changes in the money supply appear to be a relatively decisive factor in the price of gold. The coefficient of determination is close to 50%. Nevertheless, the dependence of the gold price on the money supply is not sufficient to affirm that the latter is a strategic determinant. It should also be noted that, over the very long term, the price of gold rises in roughly the same proportions as the stock market, i.e. four to five times faster than inflation.

Towards a sustainable outperformance of gold on the stock market?

Inflation in financial assets, induced by increasing money creation, gives rise to valuation cycles in financial assets. For example, government bonds gained in value from the 1980s until the historic bond crash of 2022. This crash led to major financial instability, causing intermediate banks to fail. An increase in bond volatility also leads to instability in central bank balance sheets. What's more, the long-term volatility of bonds has recently become greater than the volatility of the price of gold. The only way for central banks to reduce the volatility of their balance sheets is therefore to add gold to their inventories, which they have largely been doing since 2022.

Against this backdrop, gold looks increasingly attractive. The S&P 500/Gold ratio also points to a possible reversal towards gold's outperformance. Since the crash of 1929, the S&P 500 has outperformed gold three times: 1942-1969, 1980-2000, and finally since 2011. Overall, we can see a cycle of around 30 to 40 years taking shape on a regular basis. The recent levelling-off of the S&P 500/Gold ratio thus points to a potential outperformance of gold in the coming years or decade. Such an outperformance of the major asset classes would confirm gold's strategic role in the monetary and financial system.

Source : S&P 500 to Gold Ratio | MacroTrends

Towards a reform of the monetary system?

The inefficiency of the current system to generate growth without monetary inflation highlights the very limits of today's currencies. Despite the abandonment of the gold standard in 1971, and the sell-off by central banks in the 1990s, gold remains a strategic asset for central banks. Moreover, gold purchases are stimulated by the geopolitical situation. Many central banks therefore prefer to gain exposure to gold rather than foreign currencies, which could potentially serve as an international target.

We've already had the opportunity to point out that the life expectancy of a currency, like most major currency reforms, is more or less regular (every 25 to 30 years, read more). The growing expansion of central banks' balance sheets since the turn of the century could come up against the structural limits of increased balance sheet volatility and geopolitical instability. In this context, gold appears to meet the essential qualities of a central bank's balance sheet: independence and stability.

The accumulation of gold by many countries does not therefore constitute a gold standard in itself. The problem with a gold standard in today's world is the rigidity of the gold/currency parity. Such rigidity of gold on the balance sheet of central banks would require balanced public budgets and trade balances, which is strictly impossible for many countries today. Nevertheless, gold appears to be an indispensable asset for the smooth functioning of our contemporary monetary system. Neither government bonds, nor any other asset, can provide the essential qualities of gold, which ensure a minimum of durability for money.

According to the World Gold Council, "gold’s performance during times of crisis and its role as a long term store of value are key reasons for central banks to hold gold”. A new geopolitical instability, a new global supply shock, or increased money market volatility, would jeopardize today's currency. It therefore seems more necessary than ever for central banks to hedge with gold, in order to respond, one day, to the imperative historical need to reform the monetary system.

Central banks still neglect gold too much

U.S. gold is not directly on the Federal Reserve's (Fed) balance sheet, but on the U.S. Treasury Department's balance sheet. However, the Fed indirectly holds gold via gold certificates, worth $42.20 an ounce since 1973! Nevertheless, the Fed makes it clear that "gold certificates do not give the Federal Reserve any right to redeem the certificates for gold". It is therefore a "fictitious stock". On the other hand, under a gold-standard system, the Fed had a stock of almost $22 billion in 1948, or the equivalent of over 90% of the value of its balance sheet.

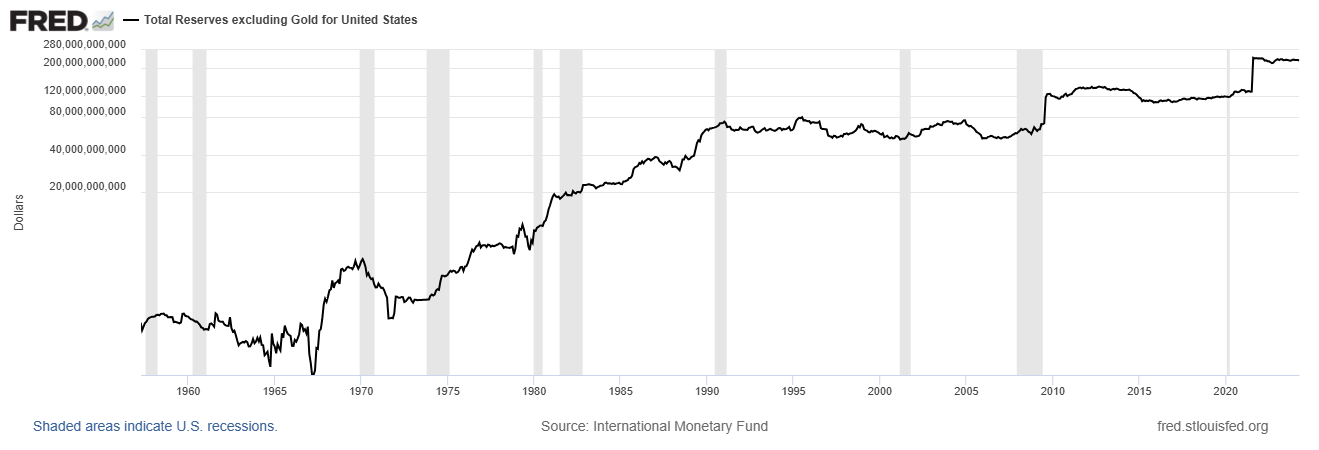

In the case of the United States, gold does not directly constitute a standard (counterparty) for the money created by the central bank. Gold is therefore largely detached from the dollar in the United States: in fact, if the Fed's balance sheet were covered by gold today, it would be equivalent to a standard of almost $28,000 per ounce of gold! The fact is, the amount of reserves outside gold stocks is increasing significantly, particularly in the wake of each crisis (see below). In the case of the US central banking system, this would mean that the Fed would be "prepared" to pay up to twelve times the current value of gold, in the event of a systemic crisis on the assets held on its balance sheet to ensure the financial stability of its commitments. Gold is still the forgotten commodity in the monetary system...

In the case of the Banque de France, the same method would result in a "balance sheet calibration" of €1,610 per ounce for the year 2021, i.e. roughly the market value of gold. On an individual basis, France therefore appears to be better covered than the Fed when it comes to gold. In the eurozone, over the last ten years, the average share of gold in the ECB's balance sheet has been close to 12%. But it is clear that the proportion of gold in central bank balance sheets has fallen significantly since the end of the gold standard.

Despite this, gold remains an essential hedge against central bank liabilities. A central bank's liabilities mainly include: banknotes in circulation, commercial bank deposits, other deposits and liabilities, and so on. Gold is the primary counterpart of "hard" money, i.e. money issued for no consideration, like banknotes. Clearly, most countries remain largely underexposed to gold. An independent, stable central monetary system would rationally require gold stocks well in excess of current levels.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.