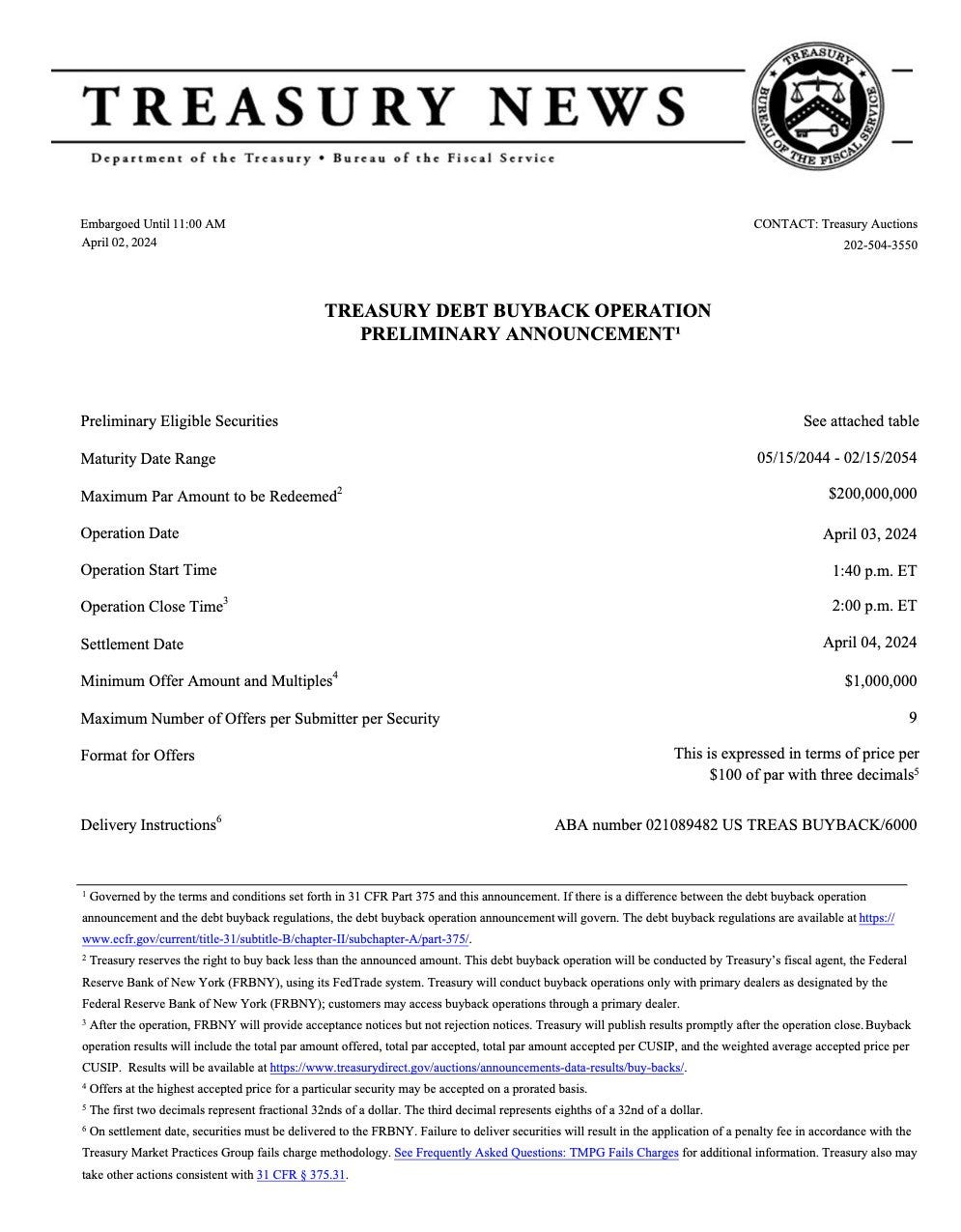

This week, the U.S. Department of the Treasury began its bond-buying program:

The U.S. Treasury has repurchased $200 million worth of Treasuries issued in recent years.

This debt buyback operation is conducted by the Treasury's fiscal agent, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York (FRBNY), through its FedTrade system. The Treasury conducts these repurchase transactions exclusively with prime brokers designated by the FRBNY; clients can access repurchase transactions through a prime broker.

The U.S. Treasury is issuing Treasuries in order to buy back long-dated bonds. This strategy is designed to inject more liquidity into a bond market that is beginning to tighten. This tension is mainly due to rising interest rates: bonds issued until 2022 are no longer finding many buyers. The intervention of the U.S. Treasury is essential to restore the proper functioning of this market, which plays a crucial role in the financial system. Treasury bills are widely used in a variety of leveraged financial products. A lack of liquidity in this market could jeopardize the very foundations of the financial system.

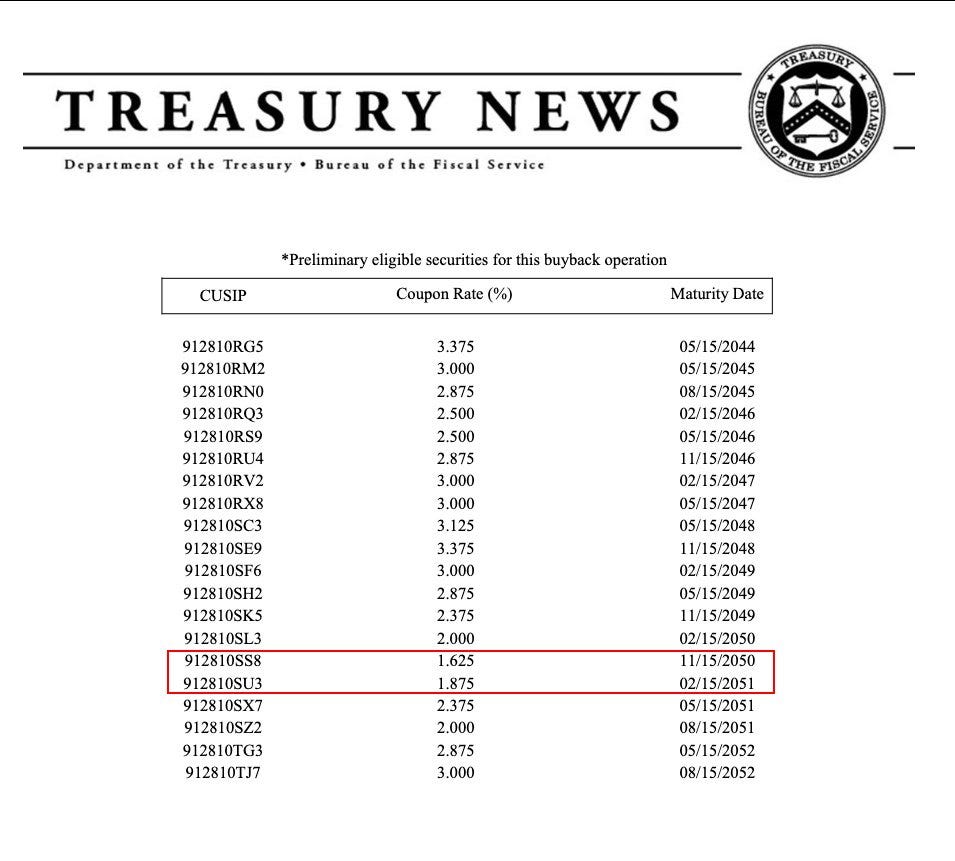

These first buyback operations concern numerous products issued between 2014 and 2022. Two of these bonds have a very long maturity date, set in 2050, with a ridiculous rate:

In effect, the Treasury bought back bonds with virtually zero yield. One imagines that these products did not find many buyers outside the Treasury itself, meaning that the market for this type of product had all but disappeared. It is crucial to limit the unrealized losses associated with these products, and restoring liquidity to these securities is essential to ensure the smooth functioning of the sovereign debt market.

The Treasury is sending a clear message to the market: even in times of bond market tension, there is now a back-up solution. The purpose of this intervention is to guarantee the continued availability of liquidity.

This is not the first time that the Treasury has used this trick to restore product liquidity after a rate hike. In fact, this policy was already implemented in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

But unlike that period, the U.S. government is not currently enjoying a budget surplus. On the contrary, the United States is embarking on a costly bond-buyback program at a time when the country is recording a record public deficit of $1.7 trillion.

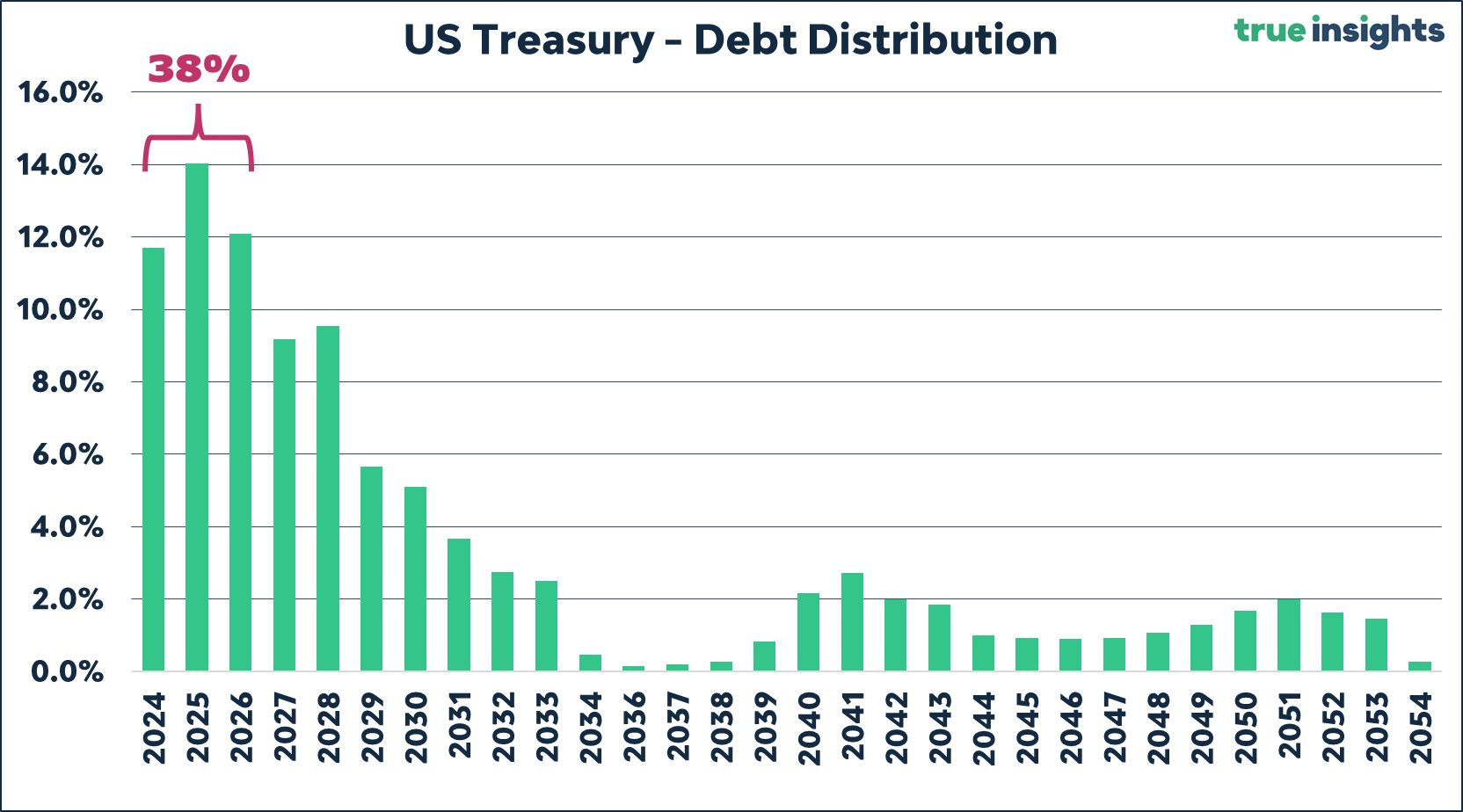

In order to buy back these long-term bonds, the government is issuing short-term bonds, even if this means further concentrating U.S. debt on very short maturities. 38% of the country's debt is already concentrated on maturities of less than two years:

One third of the country's debt must be refinanced by the end of next year.

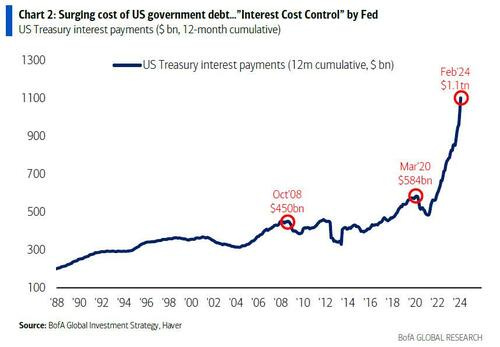

The problem is that, with 2-year rates so high, the cost of refinancing this debt is becoming ever more expensive. As a result, the annual interest cost of U.S. debt has just passed the $1 trillion mark for the first time:

Repayment of interest on the debt is becoming the largest single item of government expenditure, overtaking even military spending.

As we enter 2024, the country is on a very worrying fiscal trajectory.

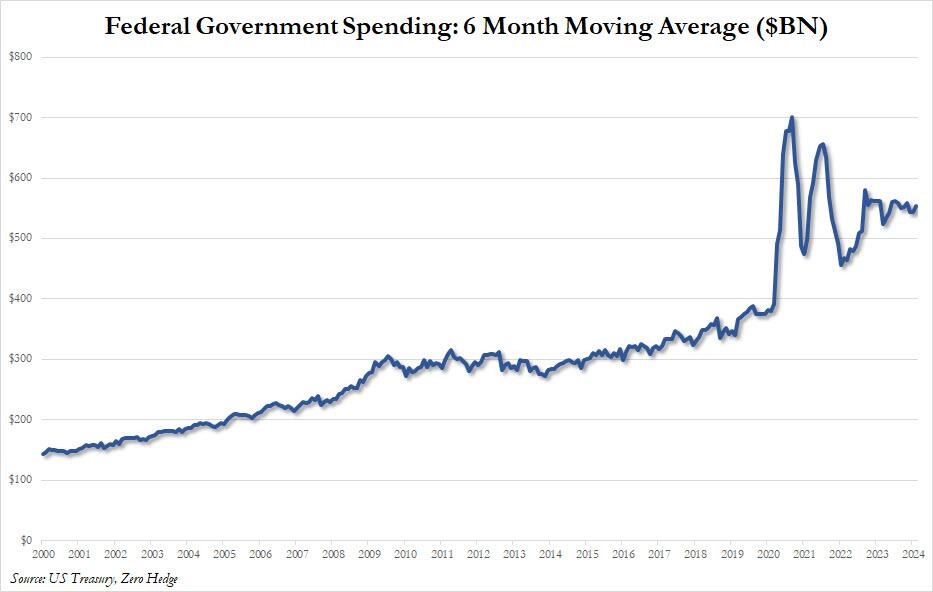

Spending continues at record levels...

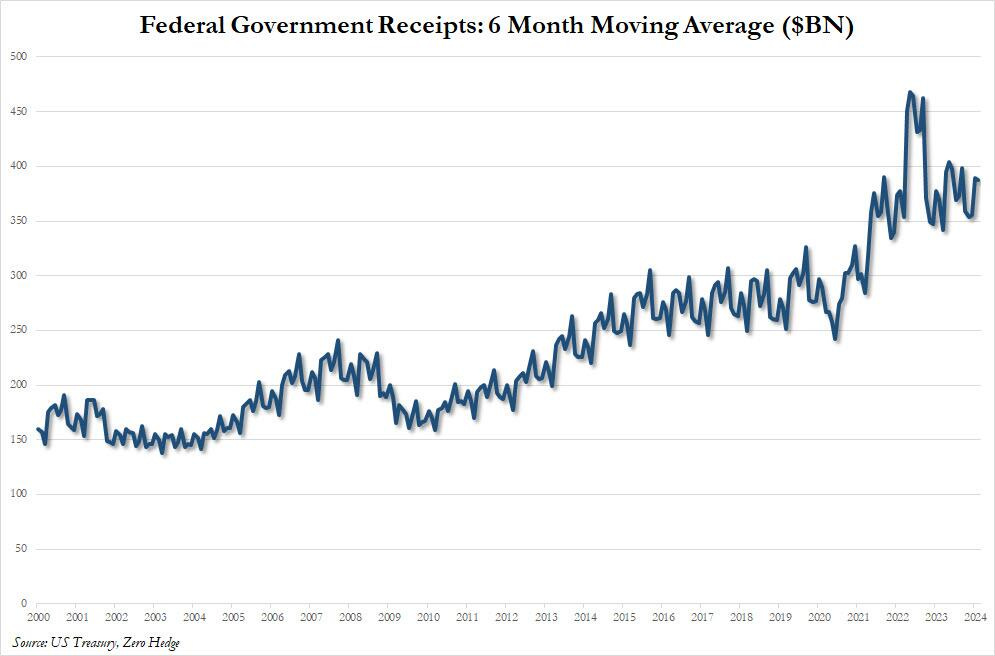

...with revenues failing to make up the deficit.

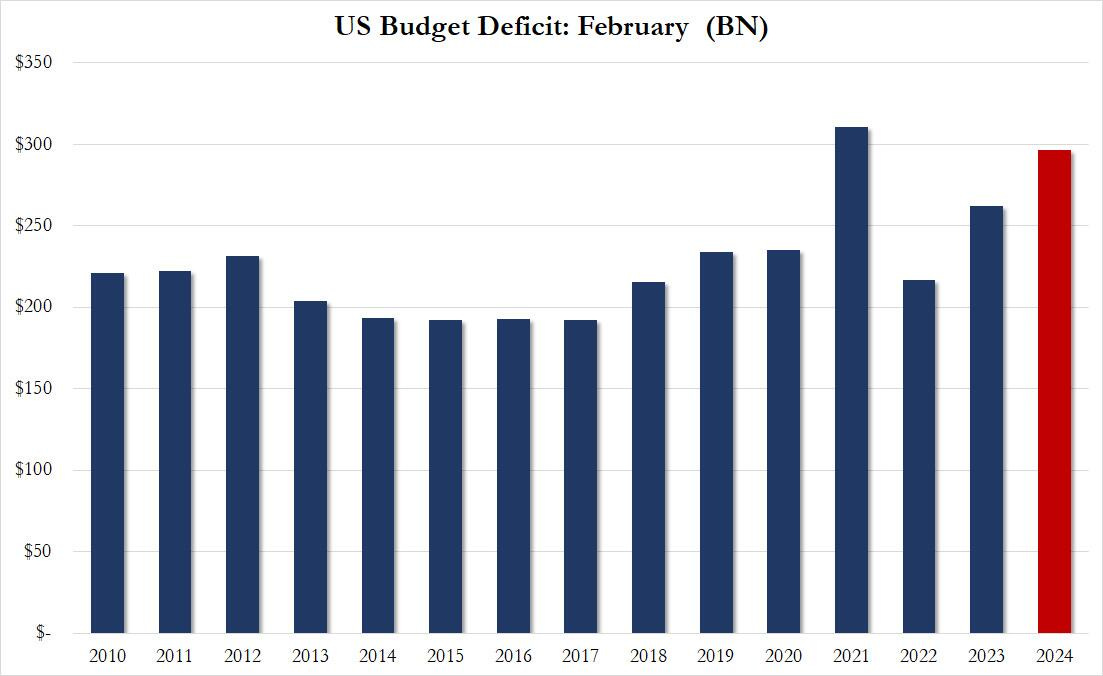

The deficit recorded in February is almost as large as that observed at the peak of the Covid crisis:

In February, the United States spent more than double what it generated.

This time, it's not health-crisis spending... The widening of this deficit comes exclusively from the rise in interest on the debt.

The Treasury injected liquidity into the markets during the Covid pandemic, leading to the first wave of inflation.

This time around, the Treasury is injecting liquidity into the market by issuing short-dated debt to finance its deficit and keep the T-bill market running smoothly.

This new injection of liquidity is triggering a second wave of inflation. Logically, this rise in inflation will not allow the Fed to lower interest rates, which will increase the cost of refinancing short-term debt.

If the Fed cuts rates just as inflation picks up again, this could be interpreted as a shift in the objective of monetary policy. Instead of focusing on stabilizing inflation, the Fed could be seen as an instrument of U.S. fiscal policy.

When a central bank pursues the objective of financing a country's debt, its currency collapses. This phenomenon can be observed in many countries. In the USA, however, this has been less obvious until now, due to the dollar's status as the reserve currency, and because U.S. bonds were considered the most stable and reliable foundation of the financial system.

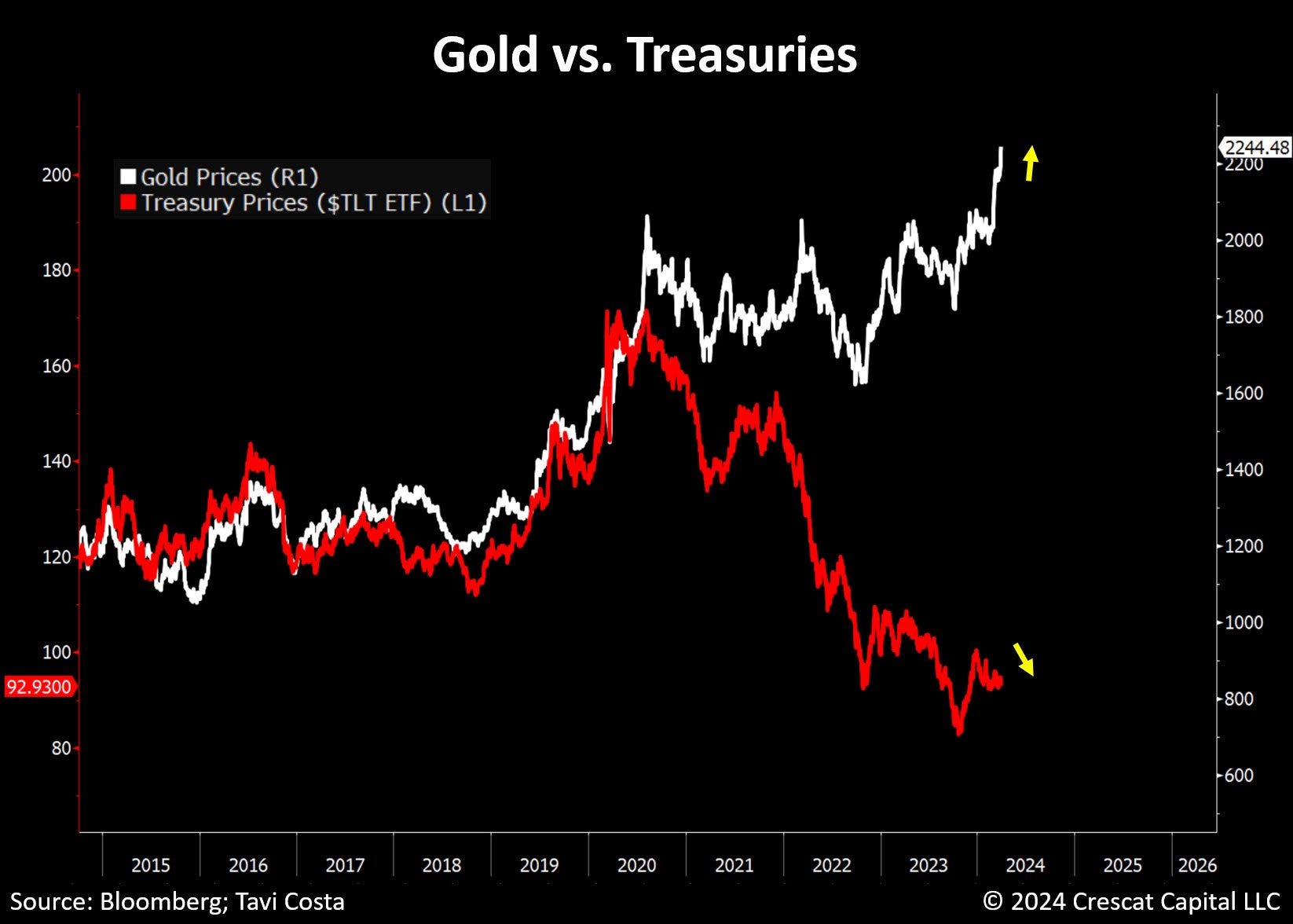

This period does indeed seem to be coming to an end, as the evolution of the gold market suggests. It seems that Treasuries are no longer considered the financial benchmark in the international monetary order:

Increased and rapid issuance of very short-dated bonds is typical of the practices observed in emerging markets, and not among issuers of the world's reserve currency and reserve assets considered to be neutral.

This headlong rush by the U.S. Treasury risks relegating the dollar to the status of a secondary currency, and turning Treasuries into risky assets.

By refusing its dual mandate of maximum employment and price stability, the Fed, by announcing a rate cut, seems to be adopting a logic of fiscal intervention. This could further weaken the dollar's place in the reserves of other central banks.

Gold purchases by these same central banks reflect the change in U.S. monetary and fiscal policies.

Moreover, the price of gold is setting new records at the beginning of this month, confirming its breakout of last month:

The other precious metal, silver, is also testing the resistance of the consolidation trend that began 3 years ago:

If silver does manage to break out of this bullish flag, short sellers on the futures markets and on the SLV ETF, who have increased their bearish positions by a record amount in recent weeks, have plenty to worry about.

Last week, a single participant added a quarter of a billion dollars in short positions in a single session on the SLV ETF.

Who can take such a risk in the face of such a surge in silver?

If silver continues its impulsive ascent, we could quickly be faced with a real short squeeze risk, due to the sheer number of short positions and the extent of leverage in this particular silver market.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.