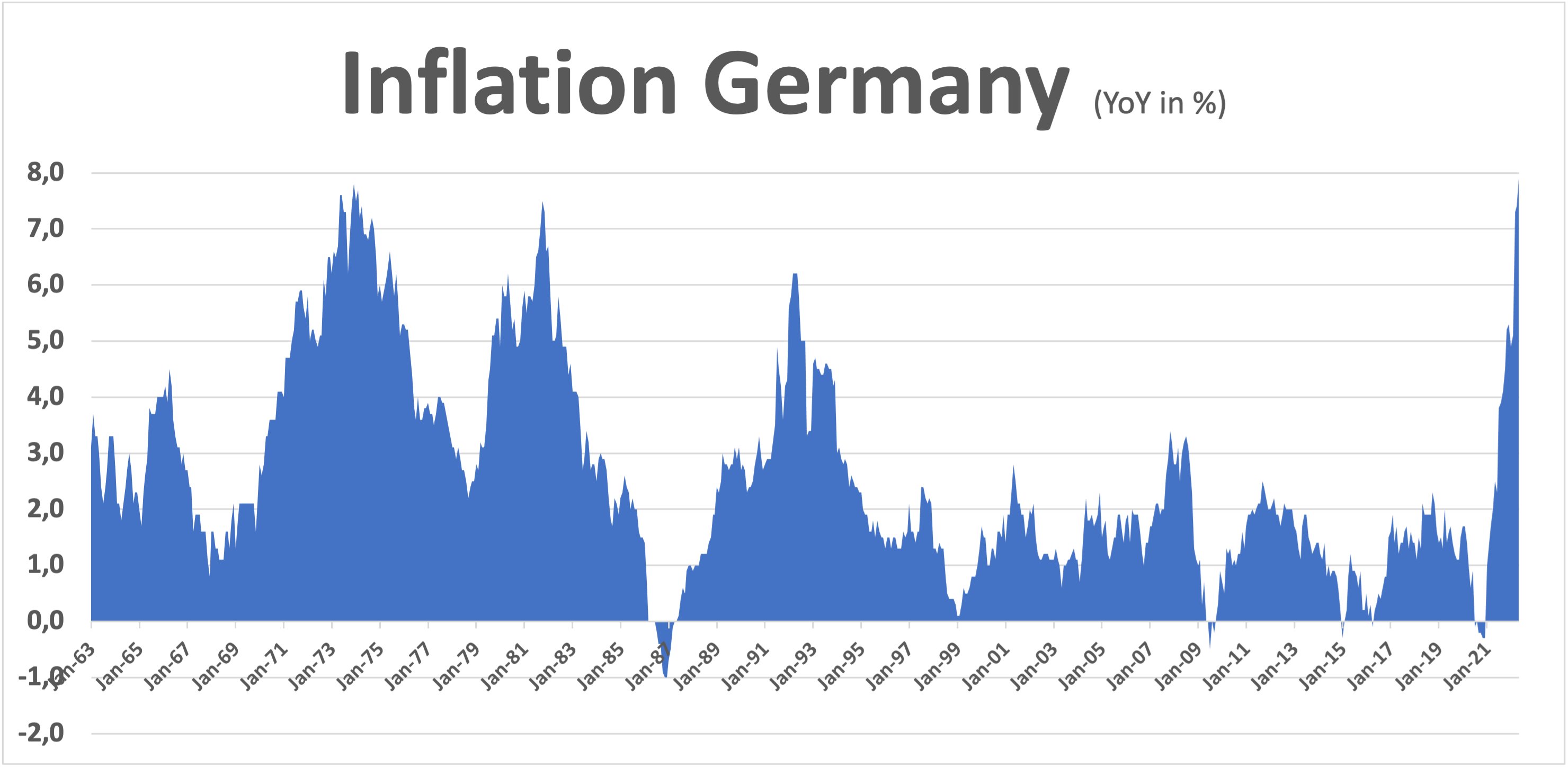

After the United Kingdom last week, the spotlight these days is on Europe where inflation figures, as expected, continue to soar. The February Producer Price Index (PPI) figures were already showing the color. What we wrote this winter is coming true: "the consequences of the current shock will have a very clear impact on the CPI indexes and therefore on consumer inflation." Today, inflation in Germany is even higher than the records of the 1970s:

With a figure of 7.9% and key rates still maintained at zero, the ECB is taking a huge risk that could plunge the continent into an unprecedented social crisis:

The differential between ECB rates and inflation has never been so high.

Inflation in Germany is the highest it has been in 60 years!

Given that the PPI is up again this month and that there is a significant catch-up margin between PPI and CPI, German inflation figures are unfortunately not about to reverse in the short term. The latest PPI figure has, in fact, climbed by +33.5% year-on-year! This is the highest figure since 1949!

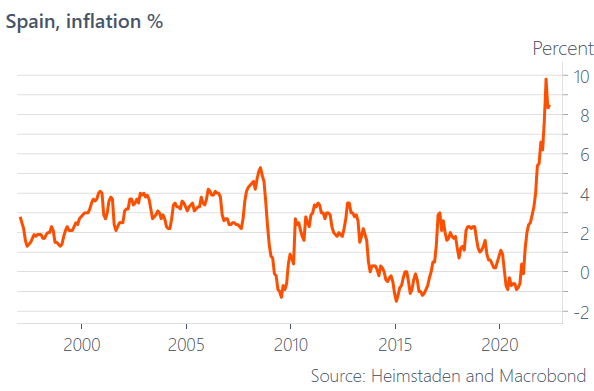

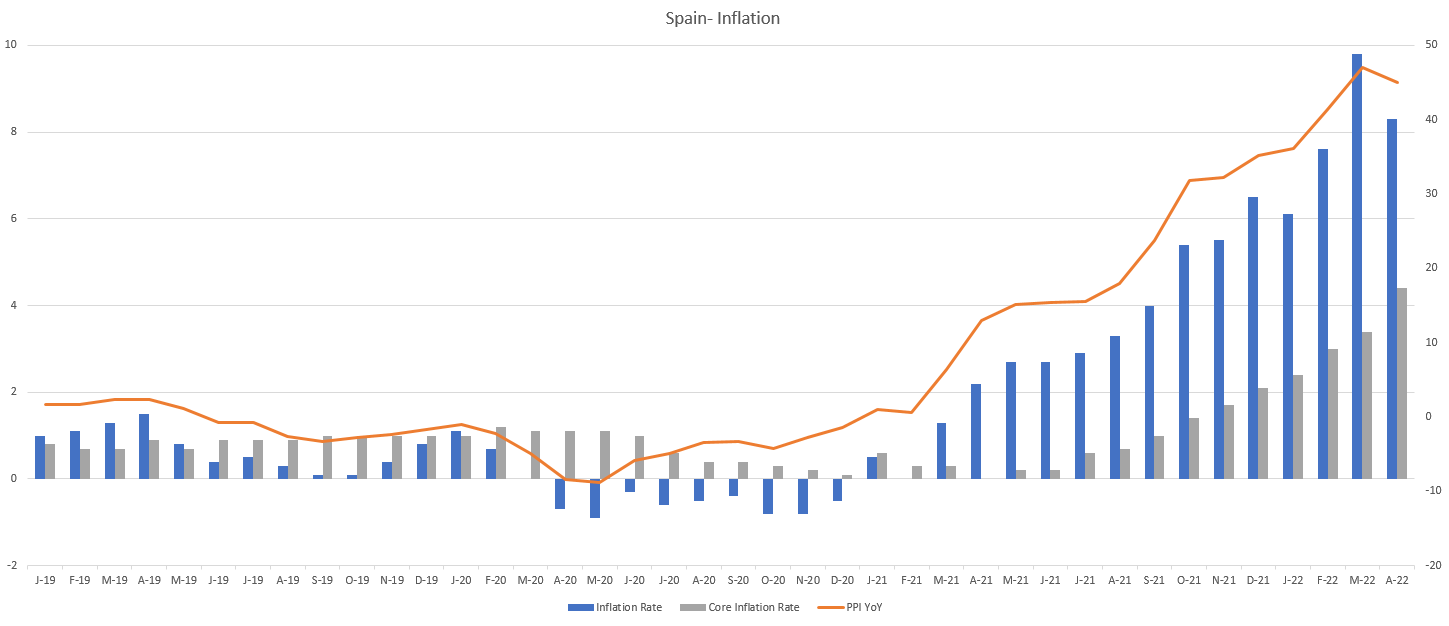

In Spain, after a lull last month, inflation is again accelerating upwards, and this is a surprise. The inflation rate stands at +8.5%, while most observers were expecting a further decline.

This new increase comes mainly from the purely structural component (core inflation):

In France, the Consumer Price Index (CPI) is at a lower level (+5.2% year-on-year - +4.8% in April), but the poor PPI figure (+27.8%) indicates a worsening of inflation for this summer.

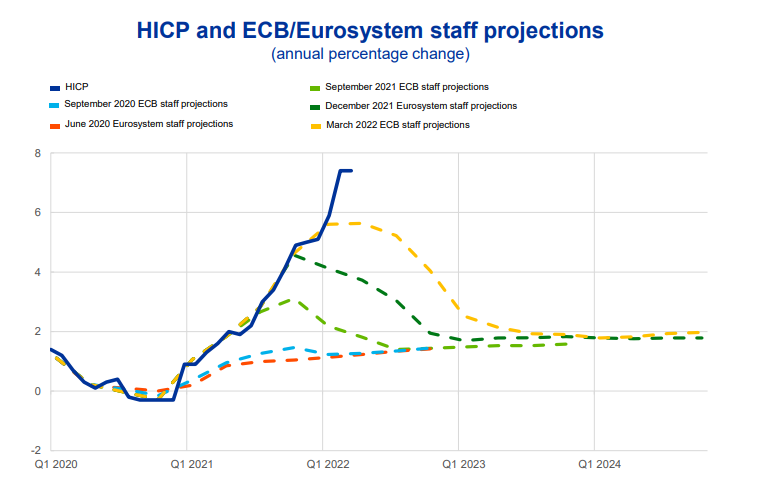

Inflation in Europe is derailing the ECB economists' five rounds of historical projections.

The European Central Bank's forecast failure will remain an example of a major error in the conduct of the continent's monetary affairs:

I challenge you to find a single board of a listed company that would not change direction after following forecasts that are so far from reality.

In the end, it is only at the ECB where such a result does not call into question the policy applied.

While the central bank is standing still, the European debt market is waking up. The ten-year rates of the southern countries (Italy, Spain, Greece) are rising again and risk once again leading to an episode of sovereign crisis within the eurozone.

This time, defending the rates of the countries of the South can only be done at the cost of worsening inflation, which is already at unsustainable levels. The ECB has much less room for maneuver than in 2011 to avoid a default by the countries of the South. Defending the sovereign debt of these countries can only be done at the cost of a significant weakening of the euro, which is socially untenable at a time when the loss of purchasing power is affecting the entire middle class in Europe.

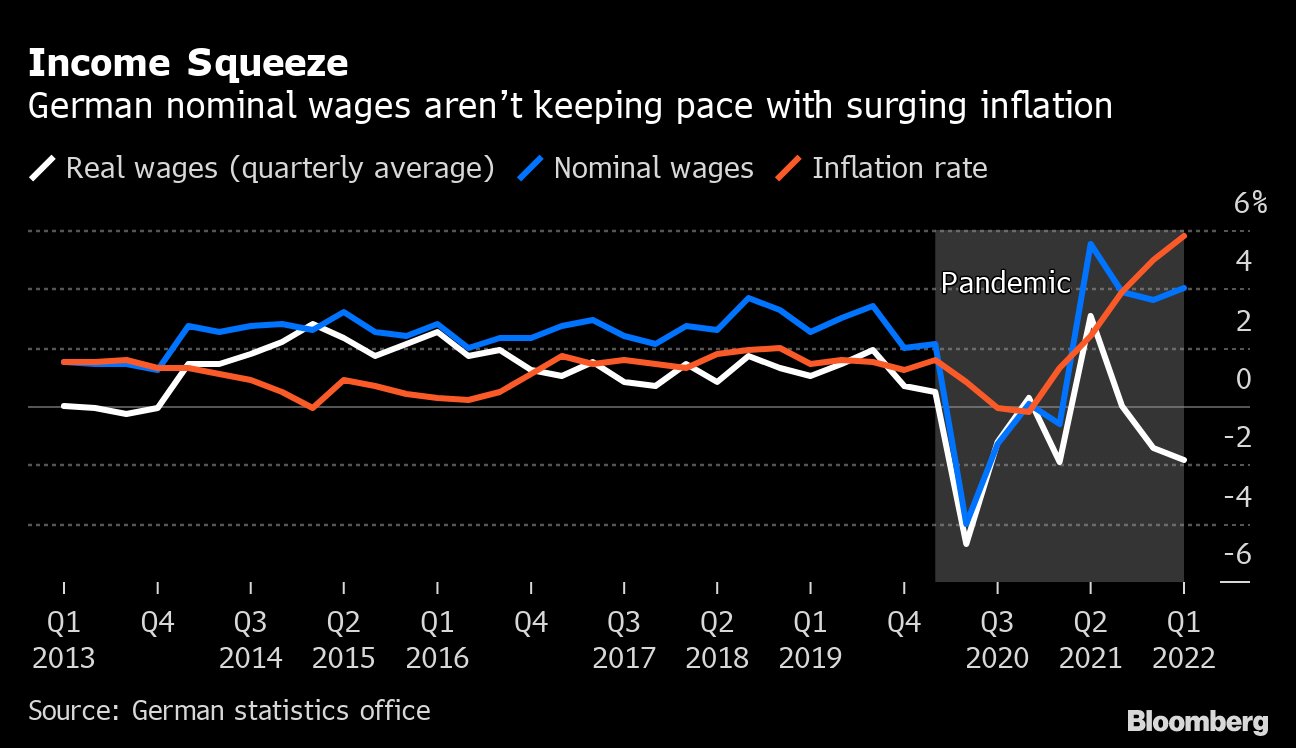

This is because, unlike in the United States, wage levels have not kept pace with inflation:

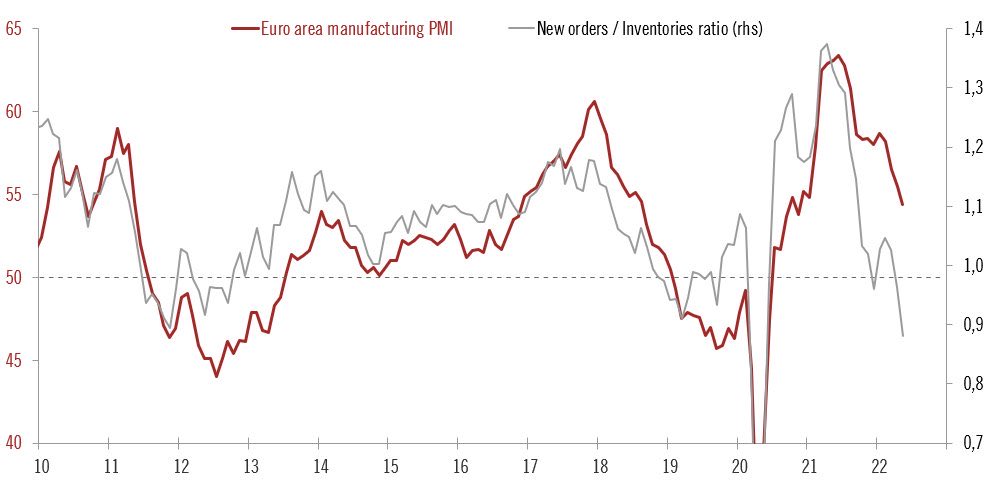

The decline in real wages may even accelerate in the coming months in Europe, at a time when industrial activity figures are experiencing a decline equivalent to that observed in 2020, at the start of the COVID-19 crisis.

The decline in orders in the eurozone is accelerating and has fallen back below the lows of 2011.

The level of the euro now reflects the ECB's inability to control soaring inflation.

This is measured in the euro/dollar parity, but also in the price of gold in euros.

The chart of gold in euros is drawing a parabolic ascension. The significant correction in the price of gold in dollars has had very little impact on this chart. It would take a radical change in the ECB's monetary policy to break this trend. Without such a change, gold may instead begin to accelerate upwards in this parabolic pattern:

The cup and handle pattern we drew at the beginning of the year has worked well. Gold prices in euros are currently testing their 2020 highs, levels that have become consolidation supports.

This situation is pushing many central banks to strengthen their gold reserves.

In the heart of Europe, we are even seeing a real gold rush.

Ales Michl, the next governor of the Czech National Bank (ČNB), announced that the country's gold reserves would increase from eleven to over 100 tons upon taking office.

After Poland and Hungary, a third Central European country has decided to increase its gold reserves.

Gold is logically regaining its stable monetary value in an increasingly tense geopolitical context, at a time when the energy future of the European continent poses many questions and when the risks of stagflation have never been so great since the Second World War.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.