Can the Fed ensure a soft landing for the economy and bring down inflation without causing a recession? This is the big economic question of the moment. It divides those who still believe that Mr. Powell has the tools to accomplish this feat and those who believe, on the contrary, that the Fed is at an impasse.

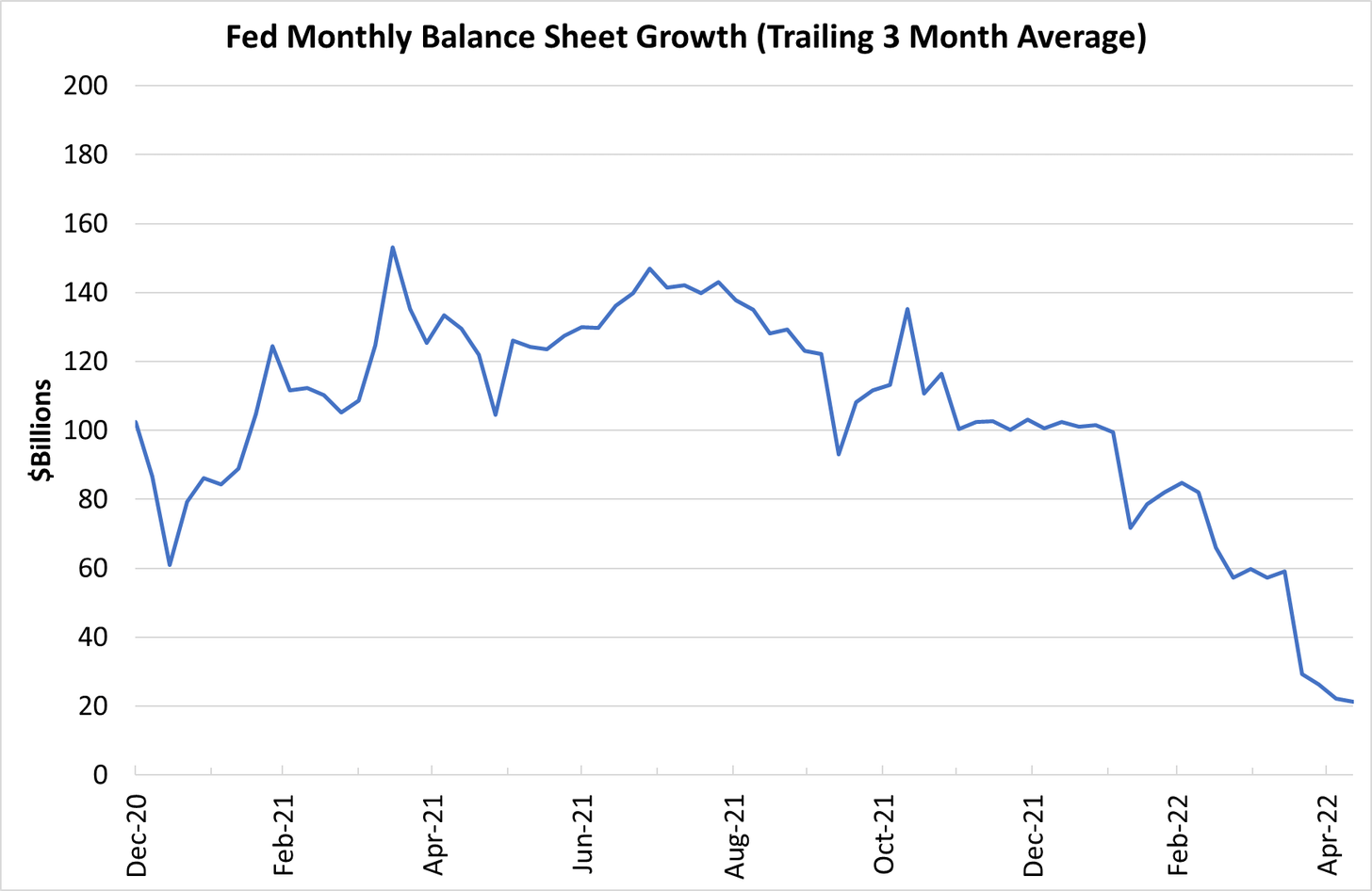

Although the U.S. central bank has not yet begun to reduce its balance sheet, it has already reduced the acceleration of balance sheet growth. If things go as planned, it should peak within a few days.

Without demand from the Fed, the supply of new U.S. debt securities may not find sufficient demand. In general, the issuance of bonds is likely to be confronted with a drastic drop in demand. After a boom in stock buybacks, the supply of equities is also becoming greater than demand. This simple fact alone explains the downward movement we are seeing in both the equity and bond markets. Without a buyer of last resort, the market has no choice but to reassess the true price of assets that have been boosted by accommodative monetary policies over the past few years. The market has less and less artificial capacity to absorb a surge in securities issuance. The decline in assets is therefore logical.

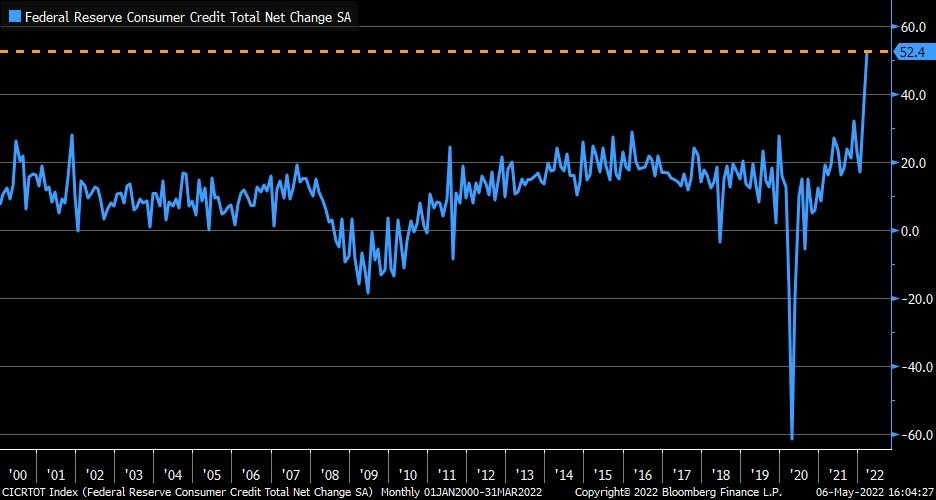

New debt issuance is accelerating, even in consumer credit. Americans have never used their credit cards more:

In the United States, consumption is holding up (retail sales figures are down only slightly this month), but at the cost of record debt.

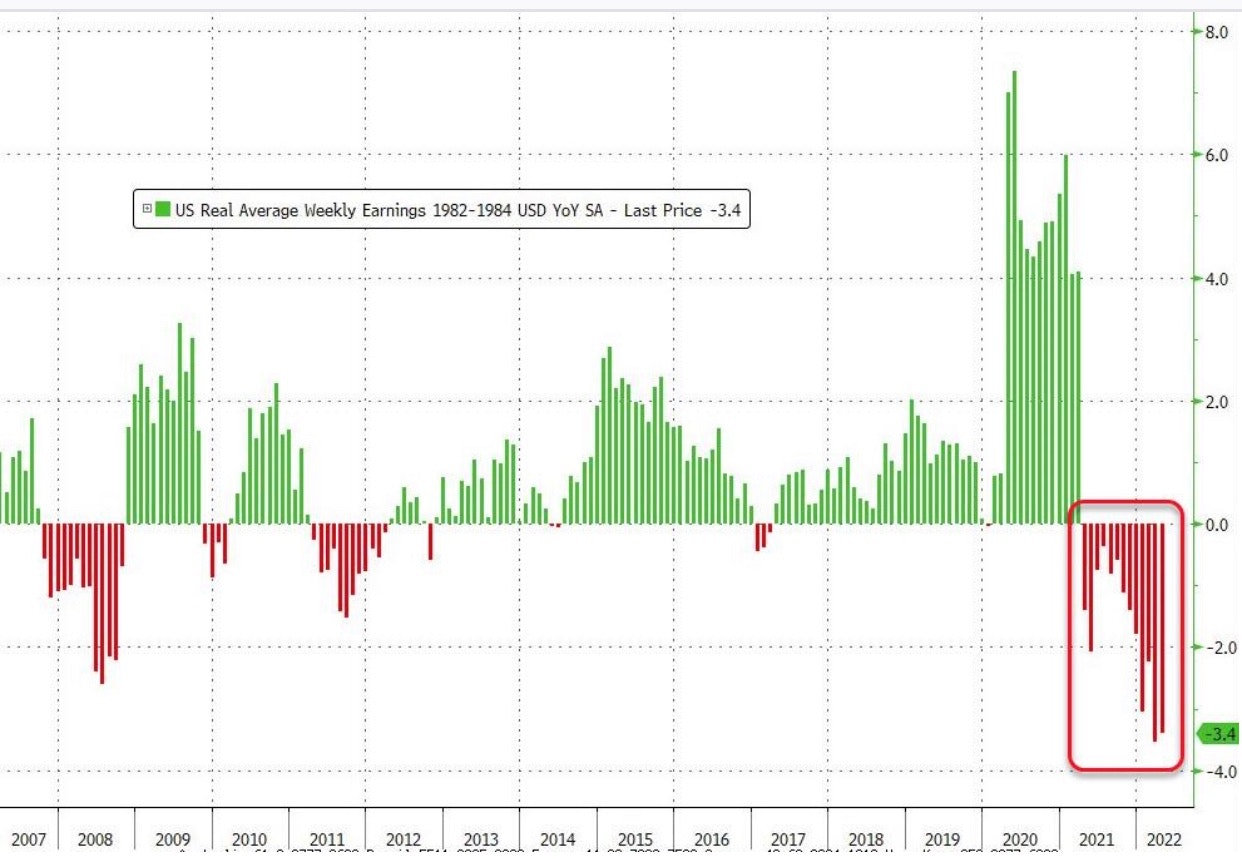

Americans are using their credit cards because their real income has collapsed:

Inflation is already depriving entire sectors of labor because wages are too low and do not keep pace with inflation. The restaurant sector is in danger in some stretched areas, precisely because of the lack of manpower.

This phenomenon leads to a unique historical situation: the unemployment figures appear to be excellent, but they mainly reflect a drop in applications for jobs that are too poorly paid in relation to the cost of living. This very low number of job applications comes at a time when the conditions for purchasing goods have never been so unfavorable, precisely because of the price level.

Usually, these poor purchasing conditions correspond to a tight employment situation. Right now, the two curves are inverted: a good unemployment figure coincides with low purchasing intentions! Inflation may be starting to reduce demand (some economists believe that we are a few weeks away from a very significant destruction of that demand, if inflation continues at this rate), but it has failed to put Americans back to work, especially in sectors where wages have not kept pace with rising prices.

The prospect of monetary tightening has already caused most assets to fall significantly.

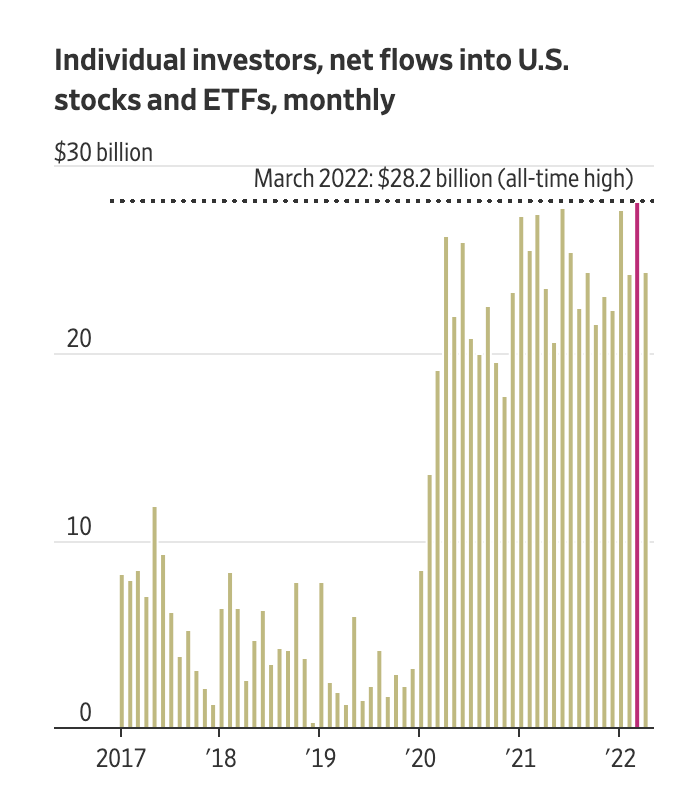

In the equity market, the decline is particularly pronounced in the retail market. We note that the real start of the stock market decline began just after a monthly record high in retail investor subscriptions...

Consumption continues to be strong in the US. We are also seeing a recovery in consumption in Europe, at some levels. This week, regional air traffic has returned to 85.5% of its pre-pandemic level, according to the network manager, Eurocontrol.

The recovery is also confirmed in China where health restrictions are gradually being lifted.

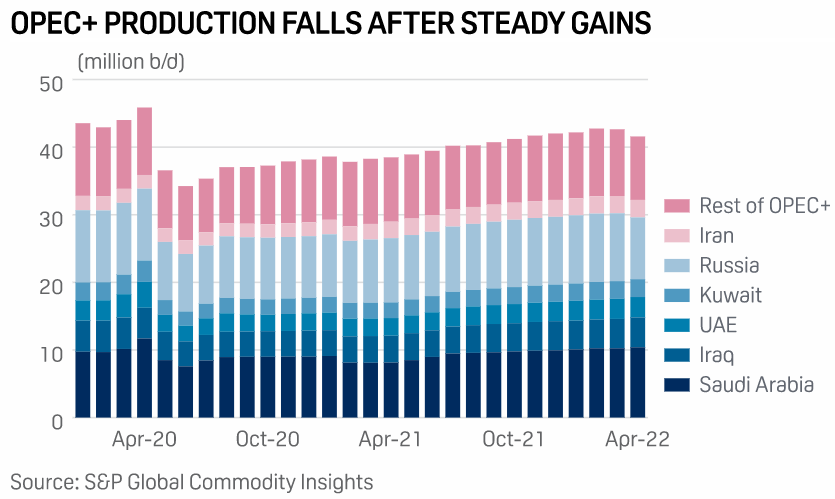

This global recovery is taking place in a context where oil supply is increasingly tight.

The supply of OPEC+ countries has never been able to recover its pre-COVID level and is even falling again in April:

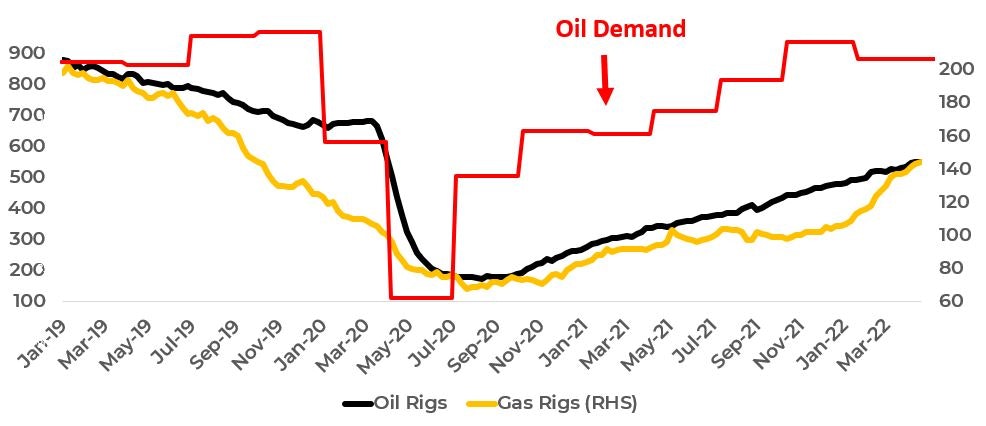

Demand for oil has already largely returned to its pre-COVID level, but extraction activity is far from being back to a level sufficient to meet that demand:

Beyond the supply of oil, it is the supply of refined oil that poses the most concern. Diesel and kerosene inventories are at historically low levels, and shortages of both refined products are likely to be a reality this summer.

We have moved from an oil supply problem to an even more challenging refined petroleum product supply problem.

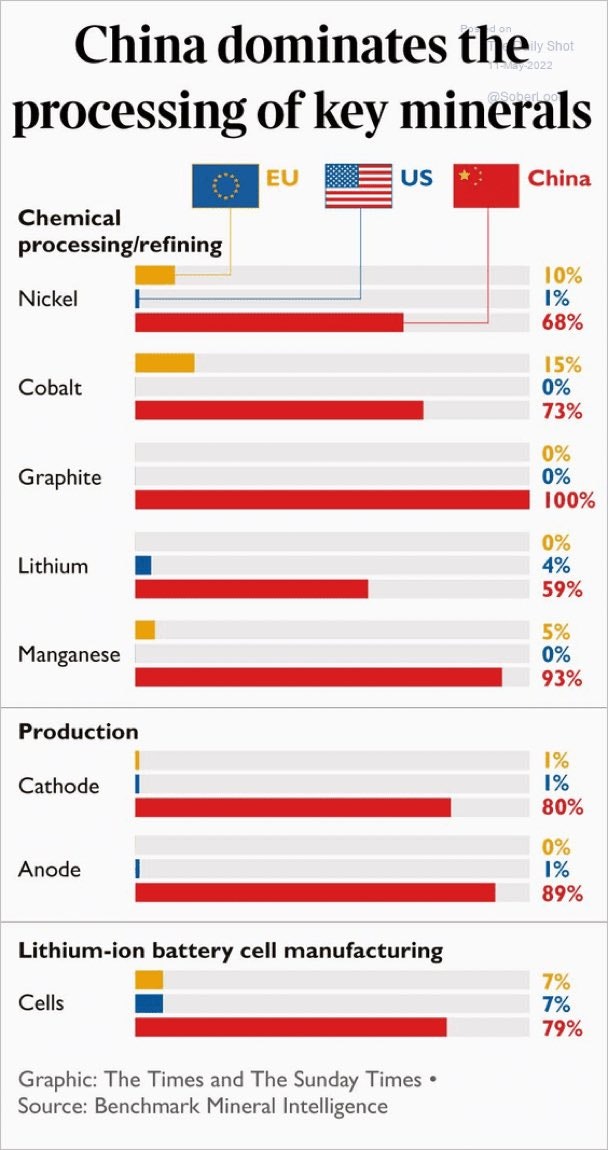

In fact, we are seeing something similar in the metals sector. Finished metal stocks depend on refining capacity, which is concentrated exclusively in China. When China stops, the entire supply of metals essential to the industry suffers.

Unfortunately, no monetary policy can do anything about the supply of essential refined products. Until this supply problem is resolved, inflation is unlikely to come down.

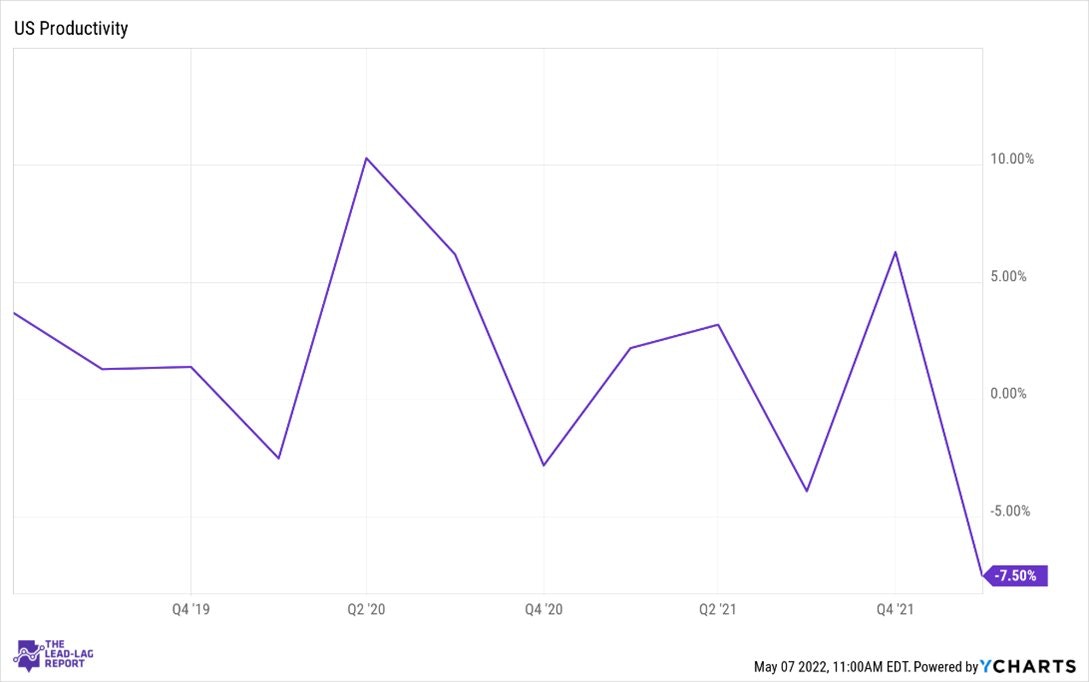

This tension on raw materials further fuels the deterioration of the geopolitical situation, as do protectionist measures that further complicate breaks in the production chain. These new conditions are reducing business productivity, which has been a deflationary driver in recent years. The decline in productivity is accelerating in the developed countries and this phenomenon is further accentuating inflation.

U.S. worker productivity is down 7.5% from last year, its worst figure since... 1947!

Rising wages, falling productivity: inflation is not transitory and is becoming uncontrollable for the Fed, because it is linked to a problem in the supply of raw materials. The Fed has decided to lower demand to fight inflation, even if it means risking an explosion of the asset bubble that its monetary policy has artificially inflated. In the 1970s, the Fed managed to burst the commodity bubble by tightening its monetary policy.

In 2022, the Fed is not in the same situation. The bubble is not at this level, but at the level of financial assets and all their derivatives (real estate, stocks, bonds, works of art, etc.). It is this bubble that the Fed risks bursting by tightening its monetary policy.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.