The bond market continues to face severe turbulence.

The British bond market has been under pressure since Rachel Reeves, Chancellor of the Exchequer in Keir Starmer's Labour government, was forced to abandon her plan to cut social spending. This sudden turnaround, which occurred against a backdrop of heated debates in the House of Commons, cast doubt on the government's ability to stick to its budget line. The market is now anticipating that Reeves will be politically weakened, and some are even considering replacing him with a more left-wing minister, perceived as being more in favor of a more aggressive fiscal stimulus policy.

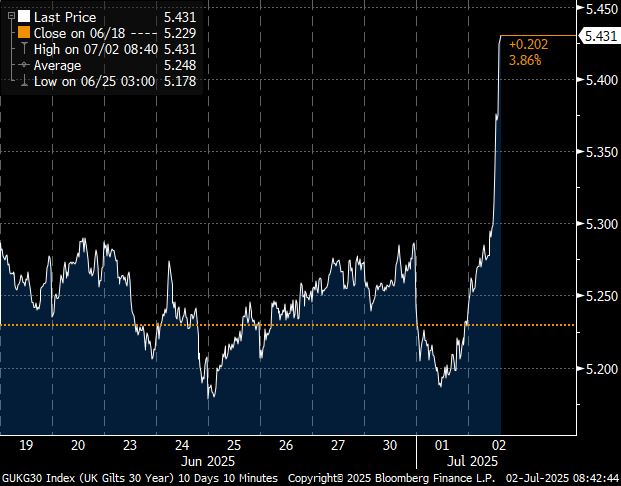

This political uncertainty had an immediate effect on long-term Gilts. The yield on 30-year government bonds jumped by over 22 basis points in a single session, reaching a level not seen since the crisis of confidence triggered by Liz Truss's mini-budget in autumn 2022:

The movement has spread across the entire yield curve, with 10- and 30-year maturities posting their steepest rises in almost two years.

The 10-year Gilt is close to breaking point:

At the same time, the sterling pound fell sharply, losing over 1% against the US dollar. This reflects international investors' distrust of the UK's budgetary path. Abandoning the planned cuts creates an estimated £5 billion hole in the public finances, jeopardizing the rules of fiscal discipline promised by the government. As a result, investors are demanding higher yields to compensate for this increased risk.

The mechanism at work is reminiscent of the one observed in 2022: political uncertainty leads to an increase in the perceived risk on public debt, which pushes up long rates, weakens the currency, and fuels a vicious circle of pressure on the cost of financing. The Bank of England, already faced with persistent inflation, finds itself trapped between the need to restore financial stability and the risk of further dampening economic activity.

The parallel with the Gilt crisis of 2022 is not insignificant. It shows just how hypersensitive British markets remain to signals of fiscal indiscipline. Today, it's no longer a program of unfunded tax cuts that's causing stress, but uncertainty over the budgetary direction of a newly-elected government. The UK could thus enter a new phase of financial tension, at a time when political and monetary stability are crucial to reassuring investors.

This episode illustrates the extent to which bond markets remain under high tension.

The Japanese 30-year yield is on the rise again at the beginning of July, continuing an abrupt adjustment across the entire Japanese long yield curve. This rise in yields marks a potential turning point in the dynamics of the Japanese bond markets, which had long remained anchored at artificially low levels thanks to the Bank of Japan's Yield Curve Control (YCC).

Since this control was gradually relinquished at the end of 2023, investors have been anticipating gradual monetary normalization. But recent movements, and in particular this tension on the 30-year, suggest that markets are now taking the lead, incorporating the possibility of a faster-than-expected tightening. This rise in yields may also reflect growing concern over Japan's fiscal sustainability, in a context where the debt/GDP ratio exceeds 250% and the aging of the population is increasing long-term financing needs.

This movement is taking place against a tense international backdrop on the fixed-income markets: the rise in US and UK long yields, questions about the US Treasury's issuance strategy, and growing nervousness about the potential loss of control over short rates are creating a widespread climate of mistrust. Japan, which has long been spared, no longer seems able to resist this global wave of long-term sovereign risk reassessment.

This stress on the long end of the Japanese curve could have major international consequences, notably via the deflation of certain yen carry trades and the return of volatility to Asian currency markets.

The intensifying friction between the Federal Reserve and the US Treasury is part of this already unstable climate, where the slightest fiscal or monetary uncertainty can trigger brutal rate reactions.

For several weeks now, an influential Bloomberg analyst, Simon White, has been warning of the systemic consequences of an uncoordinated fiscal and monetary policy in the United States, which could be described as "fiscal QE". The term refers to a strategy whereby the Treasury issues massive amounts of short-term debt (T-Bills), while the Fed prepares or begins to cut its key rates. The apparent aim is to avoid increasing the cost of long-term debt, by borrowing only on very short maturities, artificially cheapened by central bank policy.

This strategy is not totally new: Janet Yellen had already resorted to this bias, concentrating around 30% of auctions on short maturities.

But the worsening economic situation could well prompt the Federal Reserve to accelerate its rate-cutting program.

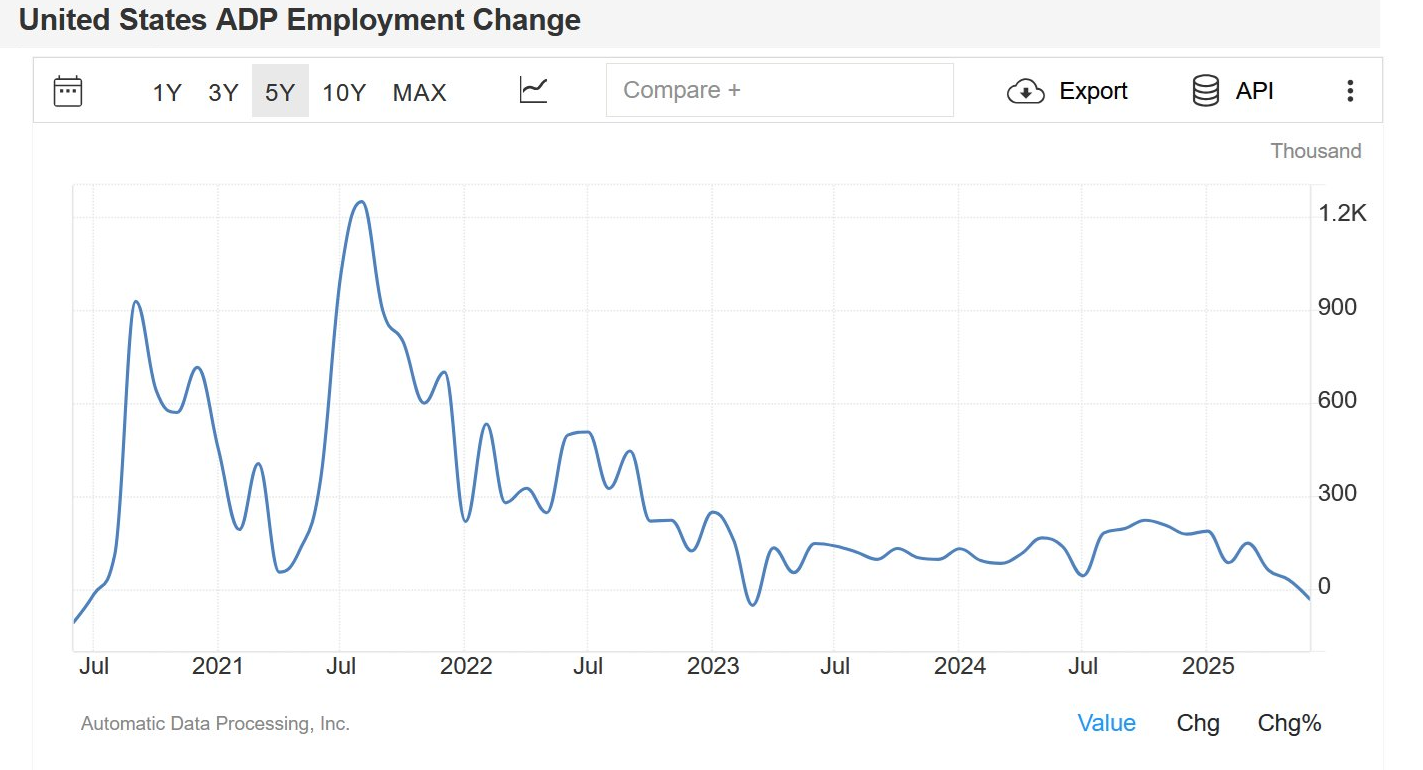

The latest economic indicators are unequivocal.

U.S. employment figures confirm a clear slowdown in the economy: in June, 33,000 jobs were destroyed, whereas the consensus was for 100,000 jobs to be created. This was the sharpest contraction in employment for several years.

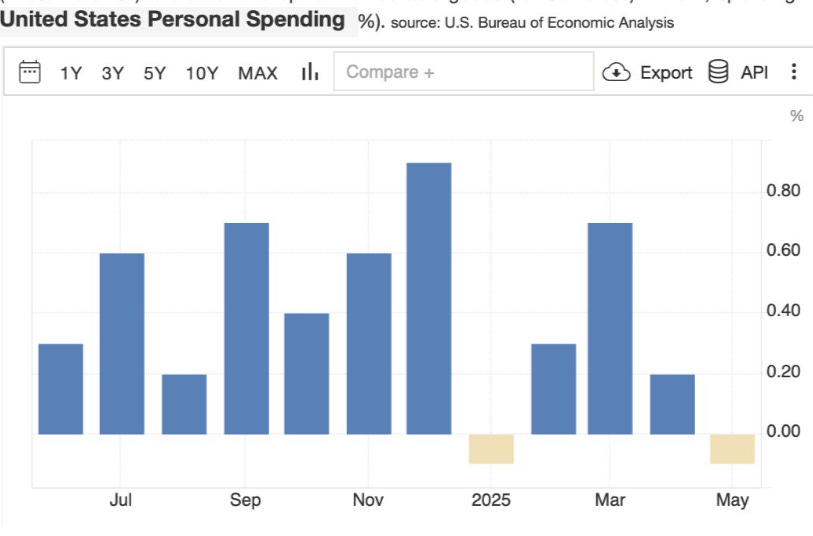

US household spending (PCE) fell by 0.1% in May 2025 compared with the previous month, to $21.441 trillion. This is the first contraction since January, when economists were expecting a slight increase of 0.1%. This weakness is due in particular to the sharp downturn in purchases of durable goods (-1.8% vs. +0.4% in April) and a more moderate decline in non-durable goods (-0.2%). Only spending on services held up, albeit with very limited growth (+0.1% vs. +0.2% in April).

More worryingly, household incomes also fell over the period, and the previous month's figures were revised downwards. This double signal of slowdown - on consumption and income - reinforces the scenario of a loss of momentum in US domestic demand, against a backdrop of growing economic tensions and uncertainty linked to inflation and trade policies.

The monthly ISM report is unambiguous. Testimony from respondents from a wide range of US industrial sectors reveals a rapid and widespread deterioration in economic conditions. Activity has slowed sharply over the past four to six weeks, under the impact of persistent trade uncertainty and a pricing policy deemed erratic.

Companies are reporting hiring freezes, cost increases in excess of budgeted inflation (+6 to +10%), and plummeting orders. In some sectors, sales have virtually ground to a halt. The global environment, marked by tensions in the Middle East, war in Ukraine and Chinese measures on rare earths, is fueling a climate of strategic confusion.

Supply chains are increasingly affected. Several manufacturers estimate that it will take years to re-establish domestic production capable of meeting demand. Investments are frozen: electric vehicle projects are postponed or even cancelled, and capital expenditure is put on hold pending greater visibility.

The term most often cited by respondents is “uncertainty”. This unhealthy climate is already weighing on activity in 2025, while the outlook for 2026 has been revised sharply downwards.

Faced with these worrying signals, the Federal Reserve may have to accelerate the timing of its rate cuts, to avoid a tightening of financial conditions.

Scott Bessent intends to go further than his predecessor Janet Yellen. He is seeking to intensify the use of T-bills, to the detriment of long bonds, by betting on a rapid reduction in key rates. His objective: to take advantage of a more accommodating monetary environment to refinance, at lower cost, the wall of debt - over $7 trillion to be renewed by the end of 2025 - while keeping federal debt servicing under control. This strategy amounts to forcing a form of fiscal and monetary coordination, with obvious political and systemic risks.

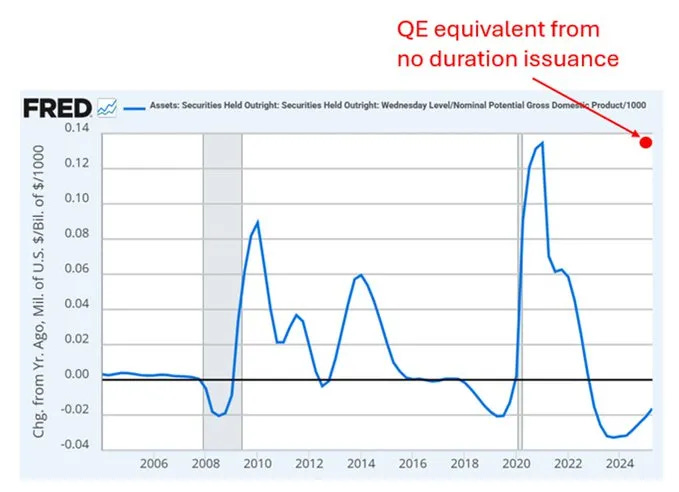

As Simon White points out, this strategy amounts to transforming public debt into quasi-money. By drastically reducing the average maturity of outstanding debt - i.e., by favoring T-bills at the expense of long bonds - the U.S. Treasury is increasing the "currency-ness" of debt: these ultra-short, highly liquid securities behave more and more like cash substitutes. This reinforces their role in day-to-day financial transactions, but in return weakens the structural stability of the yield curve.

Even if this does not constitute QE in the classical sense (no expansion of the Fed's balance sheet), this strategy is pushing investors, through the scarcity effect, away from long bonds and into riskier assets. In his view, this amounts to an implicit form of Treasury-led QE.

Analyst Bob Elliott estimates that the impact on financial markets of an outright halt to medium- and long-term bond issues (coupon bonds) would be equivalent to that of a maximum Quantitative Easing (QE) program. To be clear: such an "instruction", equivalent to the cancellation of $3.3 trillion of long debt in nine months, would represent an annual rate of $4.4 trillion of implicit QE. In other words, twice the pace of any official QE program in history.

But this strategy entails a major risk: completely destabilizing the yield curve, by causing a disconnect between Fed Funds (the Fed's key rate) and short-term market rates. Simply put, the market could demand higher yields on T-Bills due to oversupply, even if the Fed continues to lower rates. This would be a loss of control.

Worse still, this artificial imbalance would add fuel to the fire of an already over-financialized economy. It would rekindle speculation and re-inflate bubbles in risky assets - equities, real estate, private credit - at a time when many indicators are pointing to extreme fragility. This false QE, fueled by T-Bills, would therefore run the risk of artificially prolonging a financial cycle at the end of its course, by exacerbating the excesses already present.

This scenario is not theoretical. It already happened in January-February 2022.

Let's take a look at the chart that measures the spread between the Fed Funds rate (the key rate set by the Federal Reserve) and the yield on 3-month Treasury bills. This often-overlooked indicator is an essential advance signal of the market's confidence in the Fed's ability to steer short rates.

When the two curves coincide, this means that the market is obediently following the central bank's indications. But when a gap widens - whether upwards or downwards - it indicates a break in the transmission of monetary policy: either because the market anticipates a future rate hike or cut that the Fed is slow to acknowledge, or because a supply/demand imbalance (such as a massive T-Bill issue) disrupts the money market.

This is precisely what we saw at the beginning of 2022, when 3-month rates abruptly exceeded Fed Funds, despite the Fed's apparent inaction. Today, while official speeches speak of rate cuts, the 3-month rate is rising again. A signal that the market no longer believes in the scenario of rapid monetary easing - or that it fears another source of tension, such as a saturation of the T-bill market.

At the time, the Fed was keeping its key rate at zero, but the market, worried about inflation, was already demanding 3-month yields above 0.30%... The banks did not close this gap by arbitrage, when in theory they could have borrowed at 0% and bought T-bills, which climbed to 0.80%, to take advantage of the spread.

Why didn't they arbitrate? Because they were faced with a number of structural obstacles: balance sheet constraints (Basel III regulations), uncertainty over the duration of the time lag, reluctance to mobilize liquidity in an unstable environment. In other words, the market was already actively distrustful, and natural restoring forces were no longer working.

The question now is: will we see a repeat of the 2022 scenario? If Scott Bessent actually implements his "fiscal QE" plan, T-Bill issuance will reach historic levels. However, the first signs of tension are already perceptible: the 3-month rate is starting to rise, even as talk of rate cuts is multiplying. If, as in 2022, banks find the trade-off between Fed Funds and T-Bills too risky - due to balance sheet constraints, lack of visibility or growing mistrust - the disconnect between official Fed policy and real market rates could worsen. A situation that would considerably weaken the central bank's credibility.

Such a disconnect would be no small matter: it would call into question the Fed's ability to manage monetary policy. If the market no longer follows the Fed, the central bank's very credibility would be shaken. And if the Fed is perceived as a mere tool of the Treasury, then the dollar is likely to falter in its turn. International investors could flee the T-Bills, further exacerbating the pressure on rates.

The temptation would then be strong for the Fed to intervene again, but this time in the short term: by buying back T-Bills itself or injecting liquidity via targeted facilities. This would be a form of QE targeted at the short term. It would be tantamount to institutionalizing the monetization of short-term deficits. A very risky shift.

A scenario reminiscent of Erdogan's Turkey, where the political authorities imposed rate cuts while the market demanded the opposite. The result was a massive loss of confidence, capital flight and exploding inflation. The United States is not Turkey, but the mechanisms of monetary confidence are universal. The Fed can lower rates, but it can't force the market to believe it.

The systemic risk stems from this dissonance between politics, technique and psychology. If the short term gets out of hand, the whole scaffolding of sovereign financing can be caught between inflation, deficits and loss of control.

The Turks were aware of this risk long before their currency was destabilized. Faced with the gradual erosion of confidence in monetary and fiscal policy, they turned en masse to gold, perceived as a historic and tangible refuge. Today, Turkish households hold an estimated $311 billion in unregistered gold, much of it kept outside the banking system, at home or in parallel circuits. This phenomenon reflects a deep-seated mistrust of monetary institutions and a desire to preserve their wealth outside official channels.

Physical gold, in this context, is not just a financial asset: it becomes an instrument of economic survival and a defence against the erratic or politicized decisions of the authorities. It illustrates, on the scale of an entire country, what a collapse in monetary credibility can produce.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.