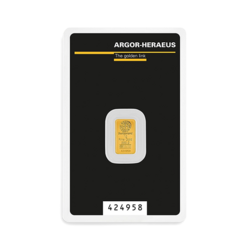

This week's chart is published by the research firm Apollo. The ongoing bank run has already wiped out $600 billion in bank deposits in the United States:

The Fed's aggressive monetary policy has caused an historic flight of deposits. Historic in its speed and size.

Never before have banks faced such a flight of customers, a movement that now threatens all regional banks not covered by the Fed's implicit guarantee.

After promising a guarantee on all deposits, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen backed down just hours after her announcement intended to calm the ongoing bank run. This about-face logically triggered panic in these small institutions.

According to a study, nearly 200 U.S. commercial banks are now in the same situation as SVB. JP Morgan estimates that a total of $1 trillion has been withdrawn from the "most vulnerable" banks in the last three weeks.

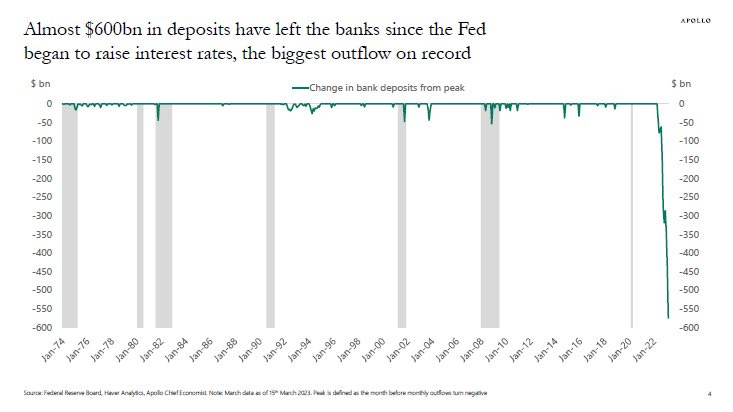

JP Morgan also indicates that half of this money is landing in government money market funds.

Goldman Sachs has calculated that the amount invested in mutual funds has reached a record $7 trillion, an increase of $282 billion since the beginning of the year:

The other half of this money is going to larger and safer banks. Smaller banks are being hit hard by the current run, while the larger banks are gaining customers.

The regional banks are even more vulnerable because they are massively invested in commercial real estate, a sector that has fallen sharply with the rise in interest rates.

The CMBS ETF, which measures the performance of this commercial real estate sector, is back down this week:

Investors face several structural problems:

- Low occupancy rates: the return to normalcy is still a long way off after the extension of teleworking in many industries.

- High debt and refinancing costs. Lease renewals for commercial real estate are particularly sensitive to rising rates.

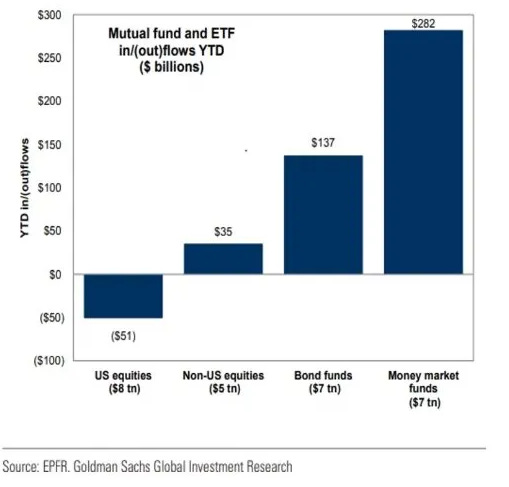

- A potential credit crunch due to the fact that regional banks are major lenders in this market. The more distressed these banks are, the more they restrict credit terms on commercial leases. And because they are the primary institutions active in this market, they are contributing to the decline in activity in the sector. Regional banks are also the largest holders of CMBS. The downward pressure on these products is all the greater because they constitute the bulk of the banks' liquidity, which they must liquidate in the current period of stress. It is precisely to avoid this downward spiral that the Fed has implemented a new tool allowing banks to exchange their CMBS at cost (and not at market price) for liquidity advances.

This mechanism, introduced as an emergency measure three weeks ago, has already significantly increased the amount of money banks borrow from the Fed:

The rush for the Fed's bailout is even greater than during the Covid-19 crisis in March 2020.

Regional banks are the most impacted, as they are the only ones to experience a bank run.

But the problem of unrealized losses on banks' balance sheets is widespread. Long-duration bond products generate monumental losses: a study published by NYU estimates the total amount of unrealized losses on the balance sheet of US banks at $1.7 trillion. According to the researchers, the total capitalization of these banks is $2.1 trillion. The total amount of deposits in the United States is $17 trillion. 10% of these deposits were unrealized losses in just one year because of rising interest rates!

Of that $17 trillion, $7 trillion is not insured by the FDIC. And even if an exception was made for uninsured deposits at the SVB, it is obvious that with such an amount of uninsured deposits, the FDIC will naturally not be able to cover all the losses in case the crisis spreads.

The situation in Europe is different, as the rise in rates has been less brutal so far. The difference in interest rates between bank accounts and government bonds has not yet forced European depositors to follow the example of their American counterparts (who are looking for a better return on their savings by transferring their cash to money market funds).

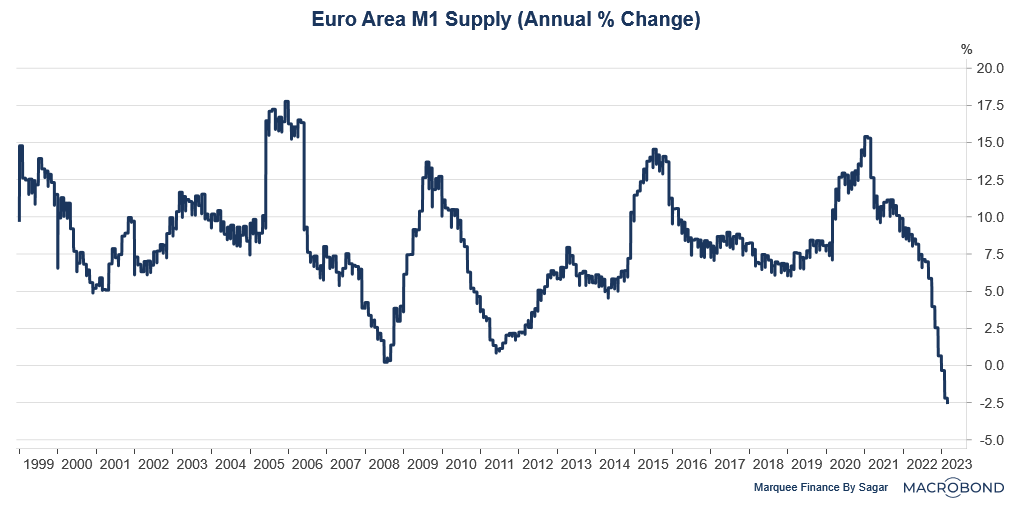

Yet, as in the United States, we are seeing a significant decline in bank deposits: the decline in the M1 money supply (which includes cash in circulation and demand deposits at commercial banks) is very significant. While this decline in M1 may also be caused by other factors such as reduced bank lending, or central bank operations, it is also largely due to the run on deposits that is affecting some European institutions.

This movement accelerated with the collapse of Credit Suisse last week.

After withdrawing $76 billion in assets from the U.S., Chinese nationals took another $165 billion out of Swiss banks, moving much of it to the Asian financial centers of Singapore and Hong Kong.

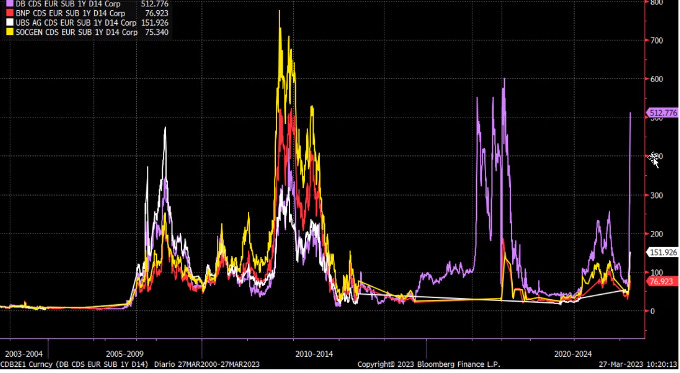

The takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS has not maintained the confidence of these clients in the Swiss banking system. The next bank to suffer from this crisis of confidence could be Deutsche Bank, whose insurance against default has risen again in recent days.

Deutsche Bank's CDS (Credit Default Swaps) are back to the highs reached during the sovereign crisis in the eurozone:

The other European banks are not affected by this stress, if the value of their CDS is to be believed. Nor are we witnessing a massive bank run like in the US.

The search of the premises of several European banks earlier this week in connection with the "CumCum" fraud, which allegedly allowed foreign investors to avoid paying taxes on their dividends from French companies, has not significantly shaken bank stocks either.

In 2008, BNP's stock collapsed by 80% in a few weeks with the contagion of Lehman Brothers' collapse. Nothing comparable to this day, neither in volume nor in magnitude.

There are now €3 trillion in bank deposits in France. Using the estimates of the NYU study and based on the same forecasts of unrealized losses in French institutions, the rise in interest rates would have already caused 10% of unrealized losses on their balance sheets: if we scale this estimate to French banks, we could estimate that they are therefore sitting on a potential loss of €300 billion. This calculation assumes that they have suffered the same unrealized losses on long-dated bond products. This assumption does not take into account the difference in rates observed on European products, as the situation is undoubtedly very different from one institution to another.

These figures show that it is imperative to avoid contagion of the banking crisis throughout the country, so that these banking institutions do not have to sell their assets at a loss to make up for capital flight.

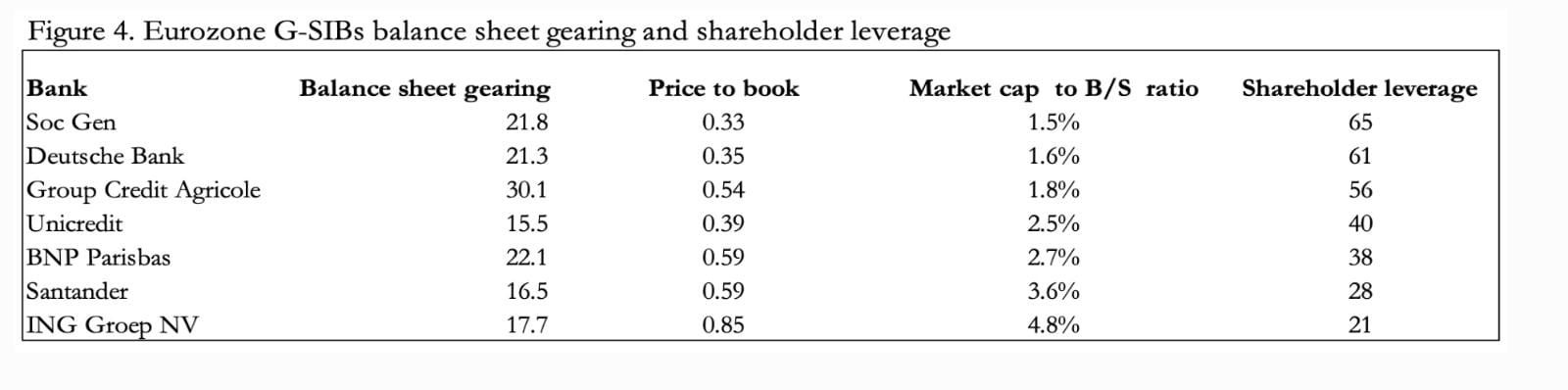

Two parameters accentuate the fragility of banks: their level of capitalization relative to their assets and their level of overall leverage. Credit Suisse's price-to-book ratio, which measures the bank's capitalization relative to its assets, was 0.24 before its collapse. In January, the French banks' price-to-book ratio was over 0.3, but the recent correction in stock prices has put these stocks at dangerous levels. SocGen's ratio, for example, is very low, currently at 0.27. The lower this ratio is, the higher the shareholder leverage is: each listed stock supports an increasingly large mass of assets... Société Générale is in the process of overtaking Deutsche Bank on this precise criterion.

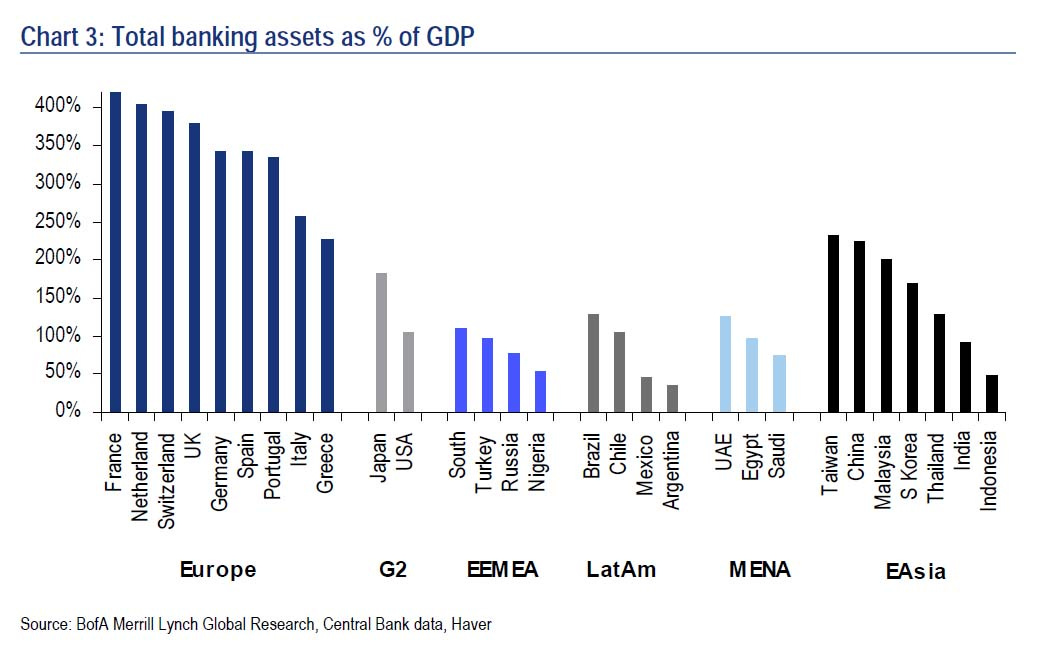

In the French banking sector, the low level of capitalization contrasts with a record volume of assets. France is the country where banking assets are the largest in relation to national GDP, which makes the banking sector a national priority, linked to the very sovereignty of the country.

The level of French banks' CDSs does not currently present any risk for these institutions, probably because of a less aggressive monetary policy in Europe, which limits the damage.

An acceleration of the rise in interest rates in Europe would threaten the French government's deficit, but it is its banking sector that would be most affected. And given its small capitalization and the very large size of its assets, it is impossible for France to envisage a continuation of the aggressive rise in rates.

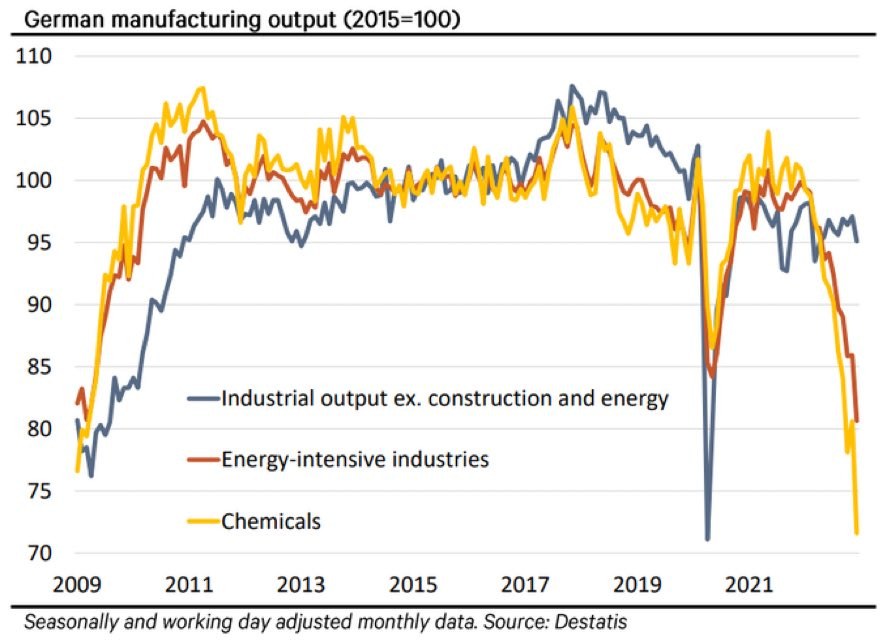

In contrast, Germany, whose main priority is to fight inflation, is encouraging this rise. The country has been much more affected by inflation than its French neighbor. And the latter has already had a considerable impact on industry and the chemical sector:

The ECB will have to make a choice between saving the French (and European) banking sector or stopping to destroy German industry. The ECB's next monetary decisions are likely to be met with a real blockade by the two countries. The consequences of the international banking crisis are accentuating the tensions between the two countries, which will weigh on the next meetings of the central bank.

In our monthly bulletin reserved for GoldBroker clients, we will analyze the consequences of this stalemate on the price of gold.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.