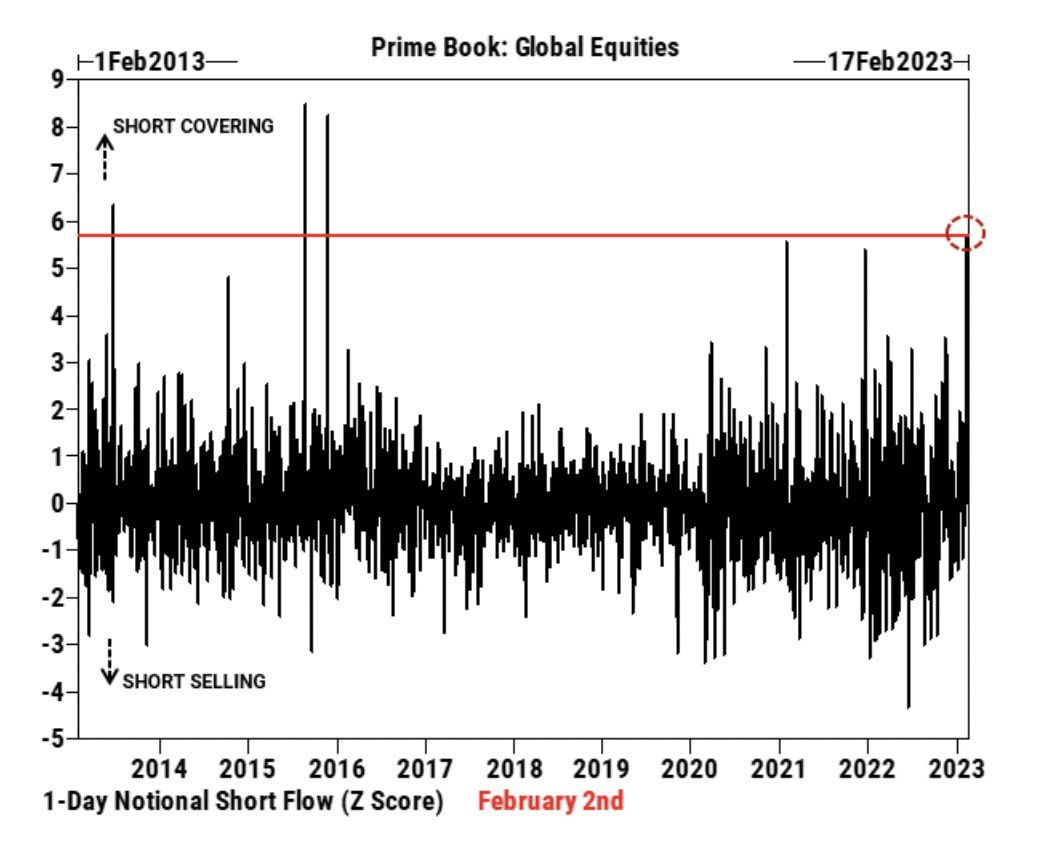

The stock markets have just experienced a bullish rally led by a short covering of a rare intensity. This is the most important short covering movement since 2016!

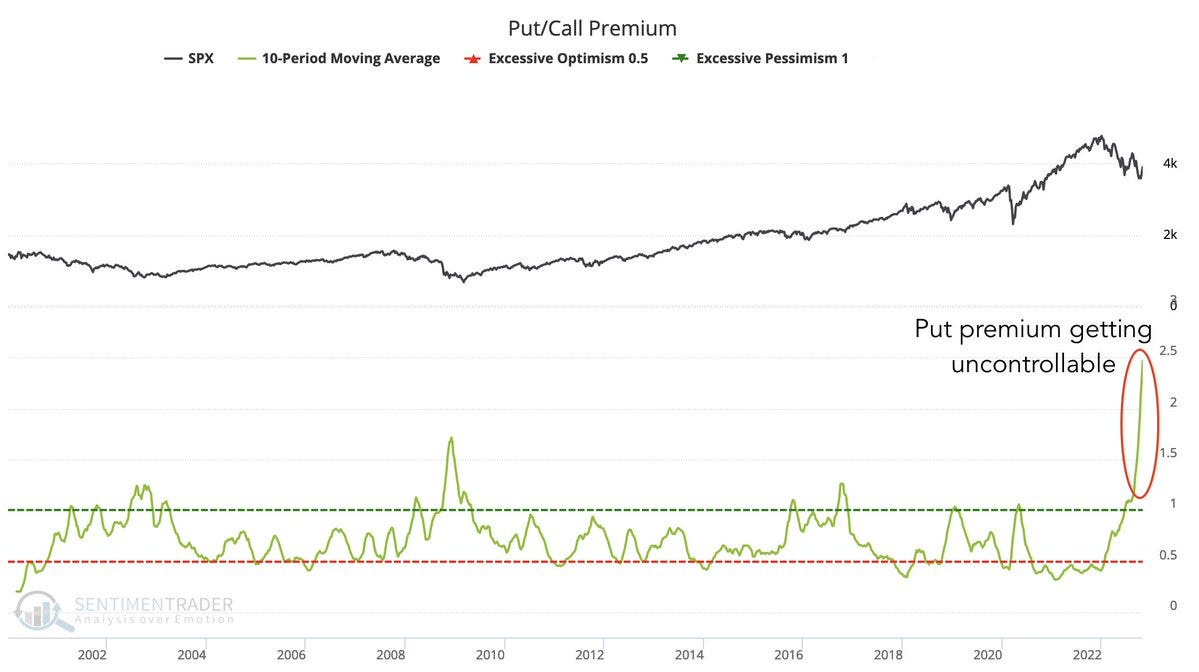

In my November 10 article, I wrote: "One major element is nevertheless protecting the indices from a downturn: the number of open bearish positions on the SPX is at a record high. These peaks of pessimism often coincide with market rebounds. Market makers love this type of configuration to initiate squeezes when too many put positions are open."

These bearish positions had been opened on justified macroeconomic considerations: with a manufacturing PMI index at 47.4 in January 2023, it was legitimate to anticipate a contraction in the production sector.

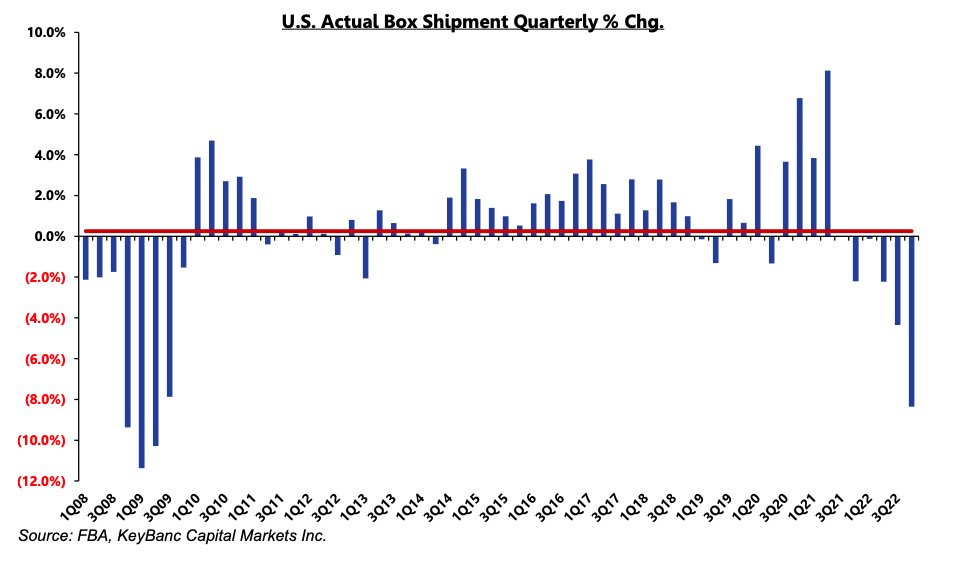

After real estate, it is the retail sector that is starting to seize up. An indicator linked to distance selling even announces an overall slowdown in internet sales in the months to come: shipments of boxes have fallen sharply in recent months and point to a fairly substantial slowdown in US consumption.

Although retail sales are still at a very high level, medium-term expectations are lower.

For the moment, the figures are far from confirming a sharp slowdown in the economy.

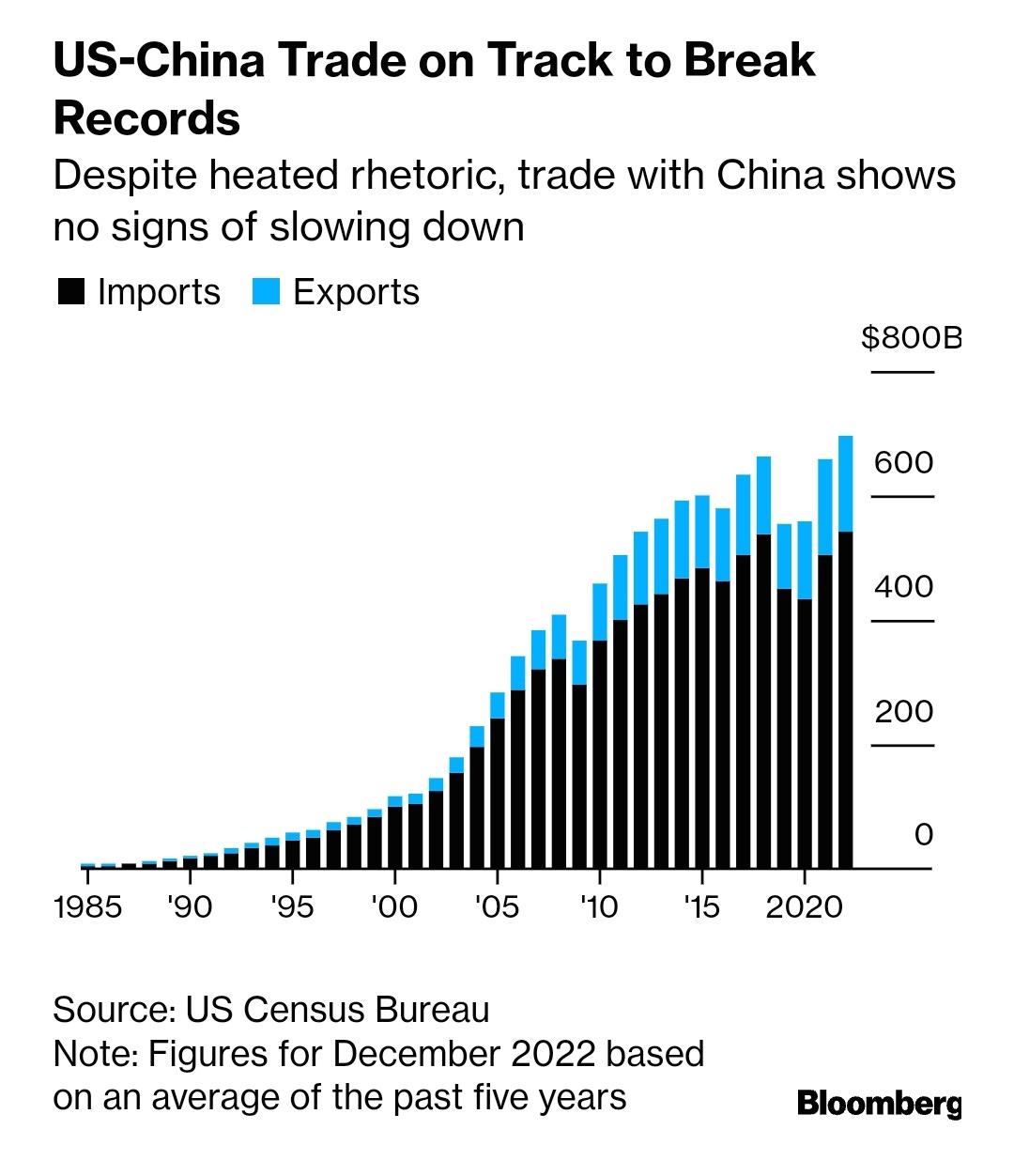

Moreover, Sino-US trade is at a record level, despite the current rhetoric about geopolitical tensions between the two countries:

The dynamism of the US economy combined with the end of lockdown in China did not confirm expectations of an economic slowdown.

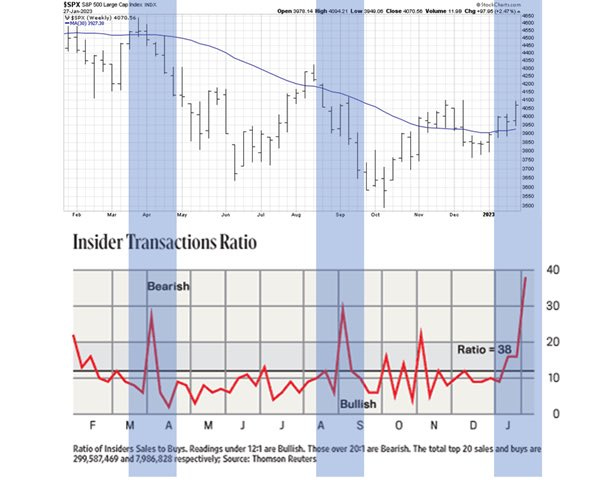

The stock market rally has been devastating for short hedge funds. In any case, it has allowed insiders who do not believe in the sustainability of this situation to sell at a record pace.

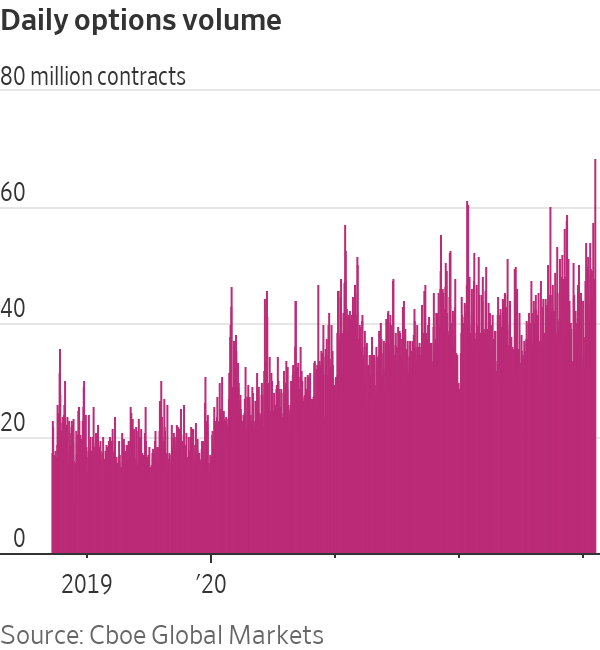

This bullish rally has also triggered an unprecedented wave of speculation in derivatives (options): short funds re-entering bearish positions, long investors trying not to miss this rebound with the maximum leverage possible...

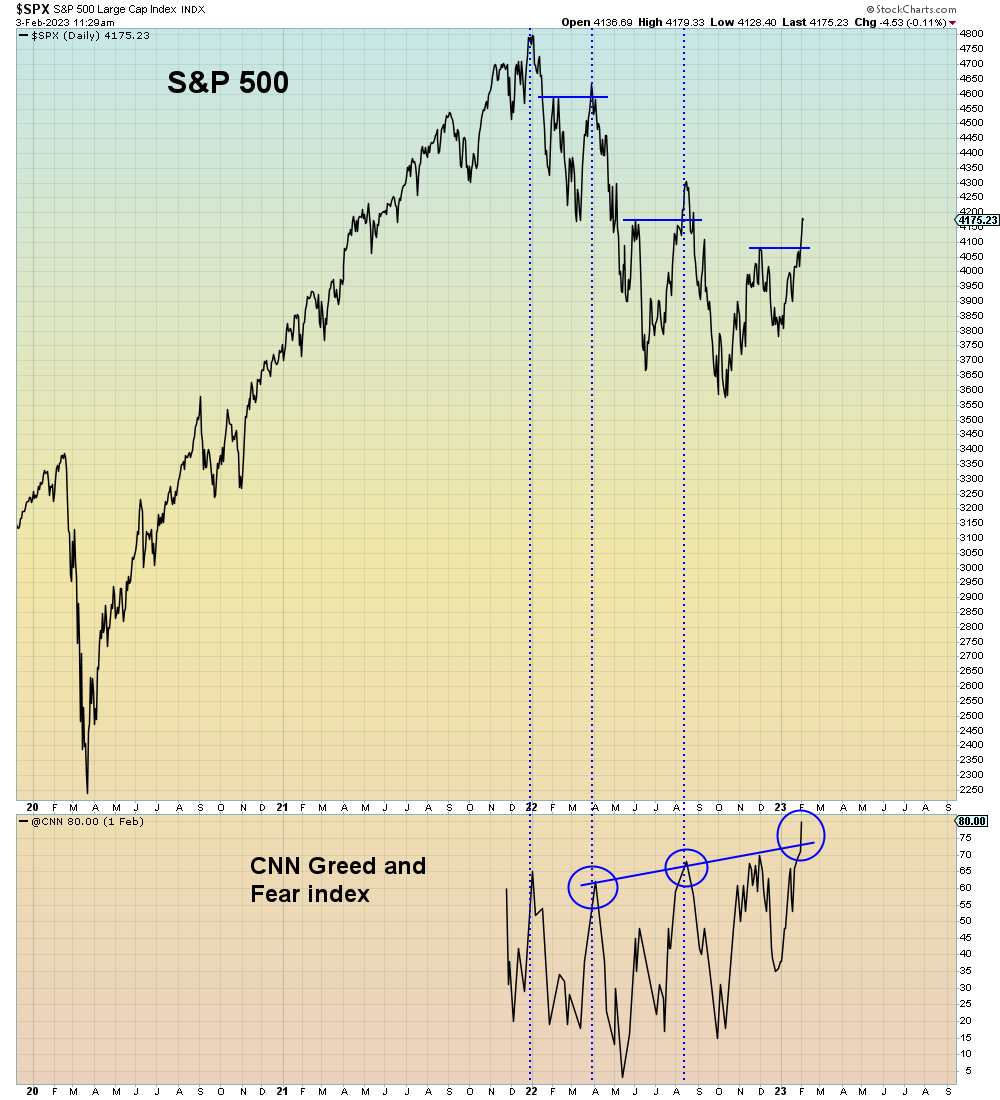

We went from a record number of put options opened in November 2022 to a record Greed Index (which measures the level of bullish speculation in the markets) a few weeks later!

If Jerome Powell thought that the rate hikes would push investors to reduce their speculative bets on the markets, he failed.

On the contrary, speculation has increased, and with it the leverage of all these bets. Americans are taking on debt to consume and more and more of them are now taking on debt to speculate in the markets.

Financial institutions have encouraged this increase in debt. They have not accompanied the central bank's firm monetary tightening rhetoric in any way.

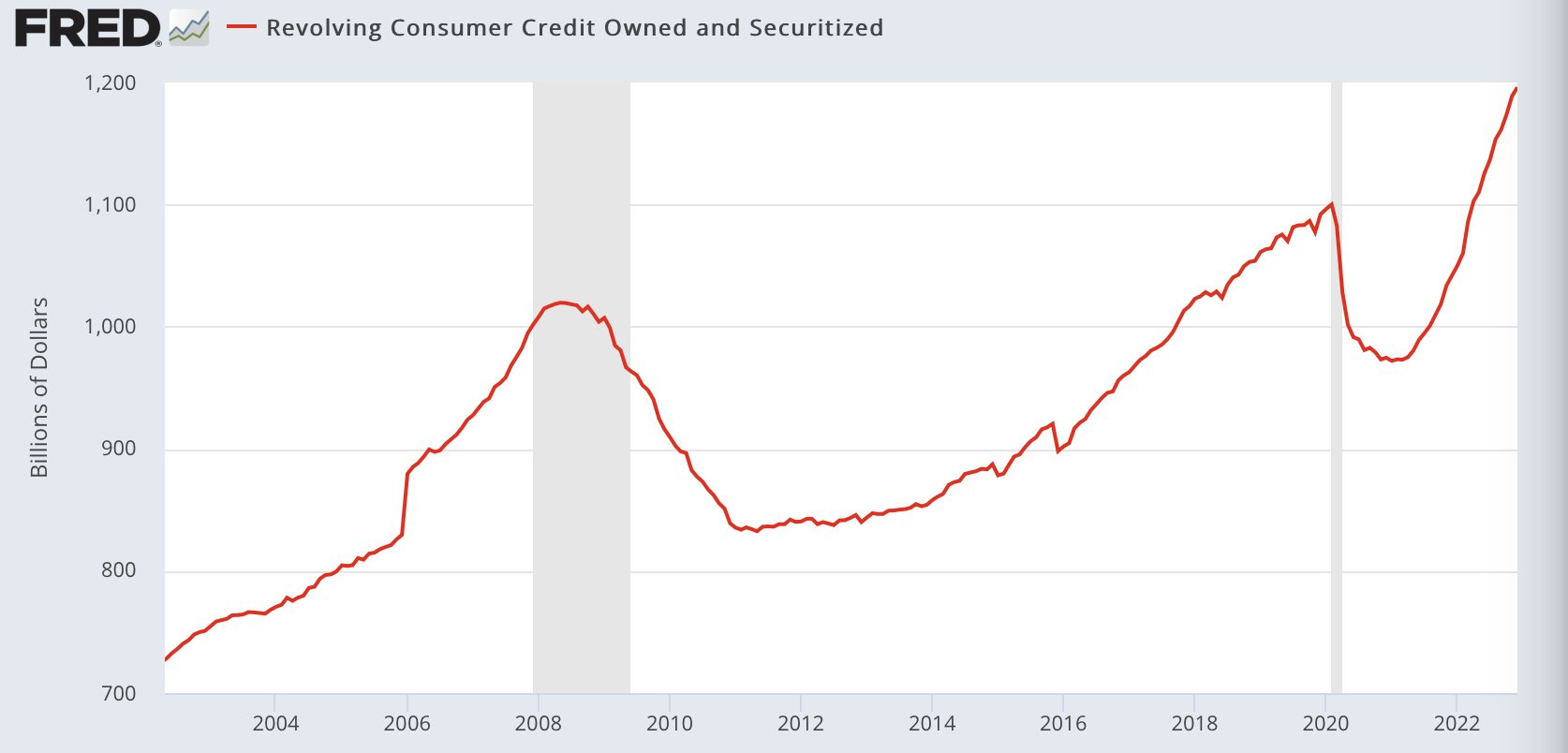

The amount of revolving credit allocated to consumers reached a record level in January:

In its latest business report, JP Morgan Bank says it is in a much better position to lend to businesses, even at high leverage levels.

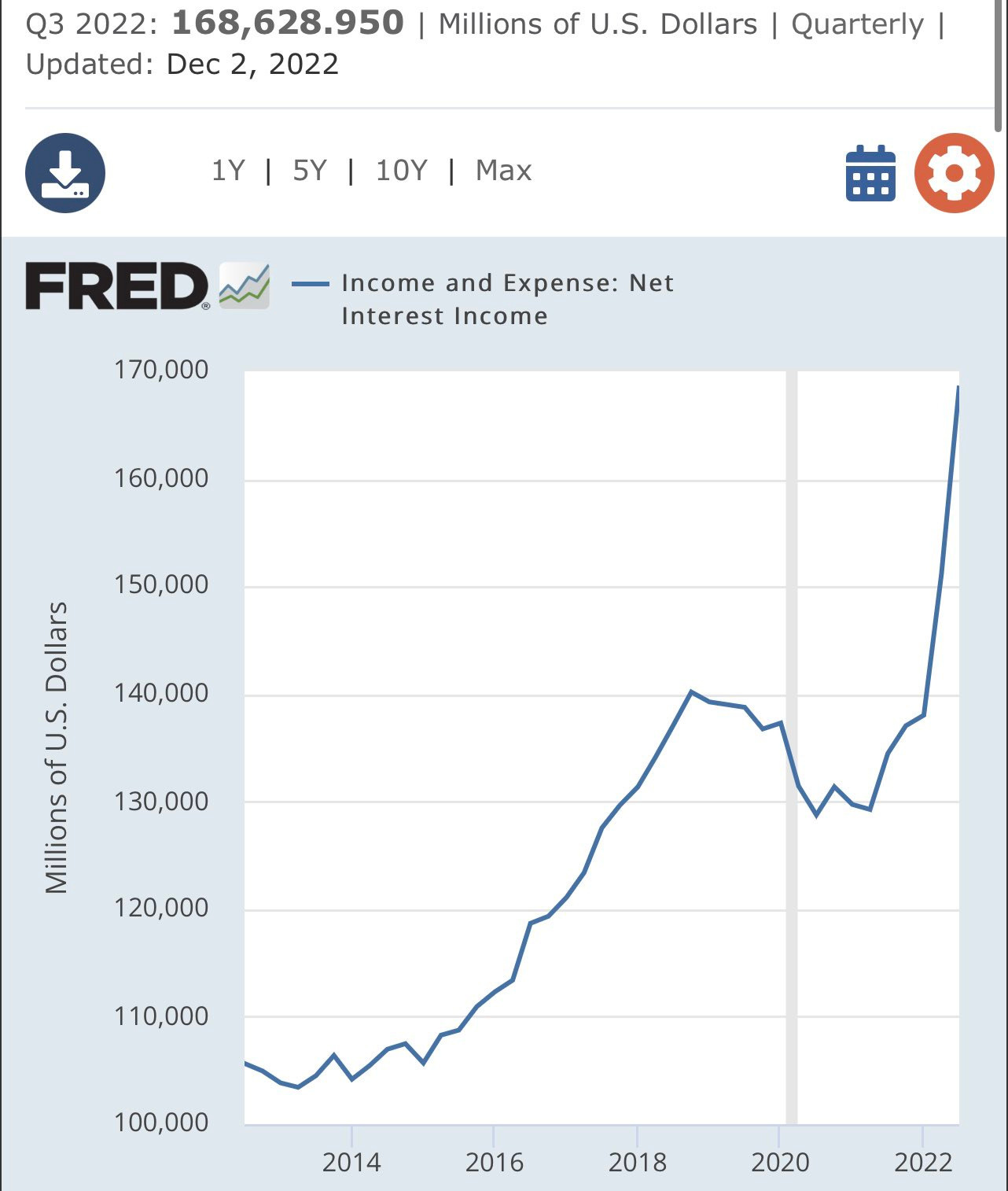

It should be said that with the rates rise, banks are now making much more money on the loans they make. Net interest incomes has skyrocketed:

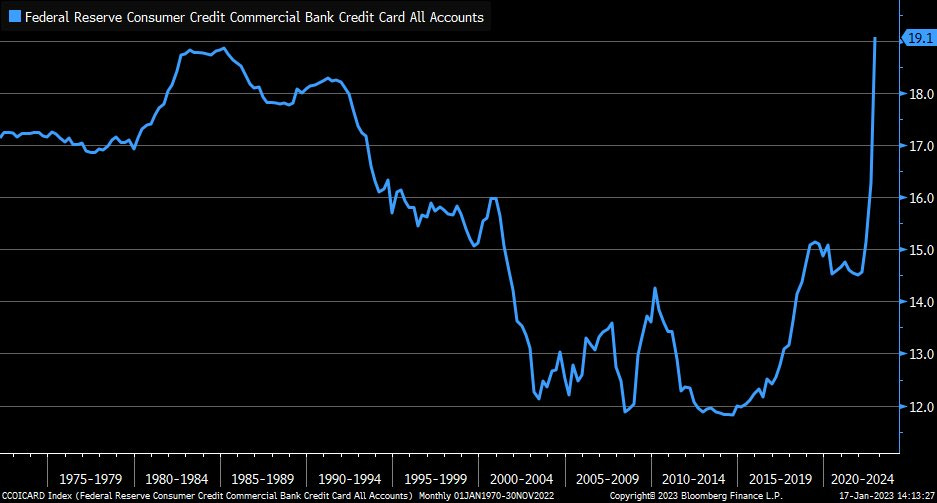

Consumers have never experienced such a high rate of repayment on their credit cards. At nearly 20%, it's even higher than in the 1980s...

In those days, to offset the costs of the credit card, you could count on a 15% rate of return on savings... what you spent on the card was offset by the earnings in the savings account. Nothing like that today. The cost of debt must be offset elsewhere. How can this be done? By holding several jobs, by changing jobs as much as possible to get a better salary! Wage inflation is the only bulwark against the rising cost of credit.

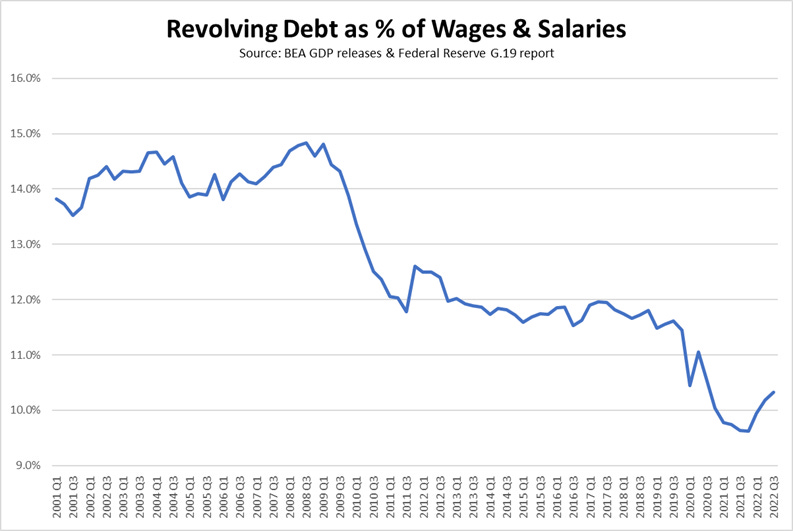

If we take the figures of the credit reserve described above and draw a chart by adjusting this reserve to the cost of wages, we get a totally different picture:

Households are taking on more debt. But for the time being, rising wages are protecting them from a "real" debt overhang that would pose real problems for banks, which are more willing to lend.

This flexibility on the part of the banks no doubt explains the robustness of American consumption.

A very tight labor market, broad access to credit that supports record consumption, upward pressure on wages, stronger-than-expected retail sales stimulated by increased trade with China... The Fed has not yet succeeded in provoking the slowdown in demand needed to rapidly ease inflationary pressures.

Under these conditions, the Fed's "pivot" is moving away and growth companies are likely to pay the price.

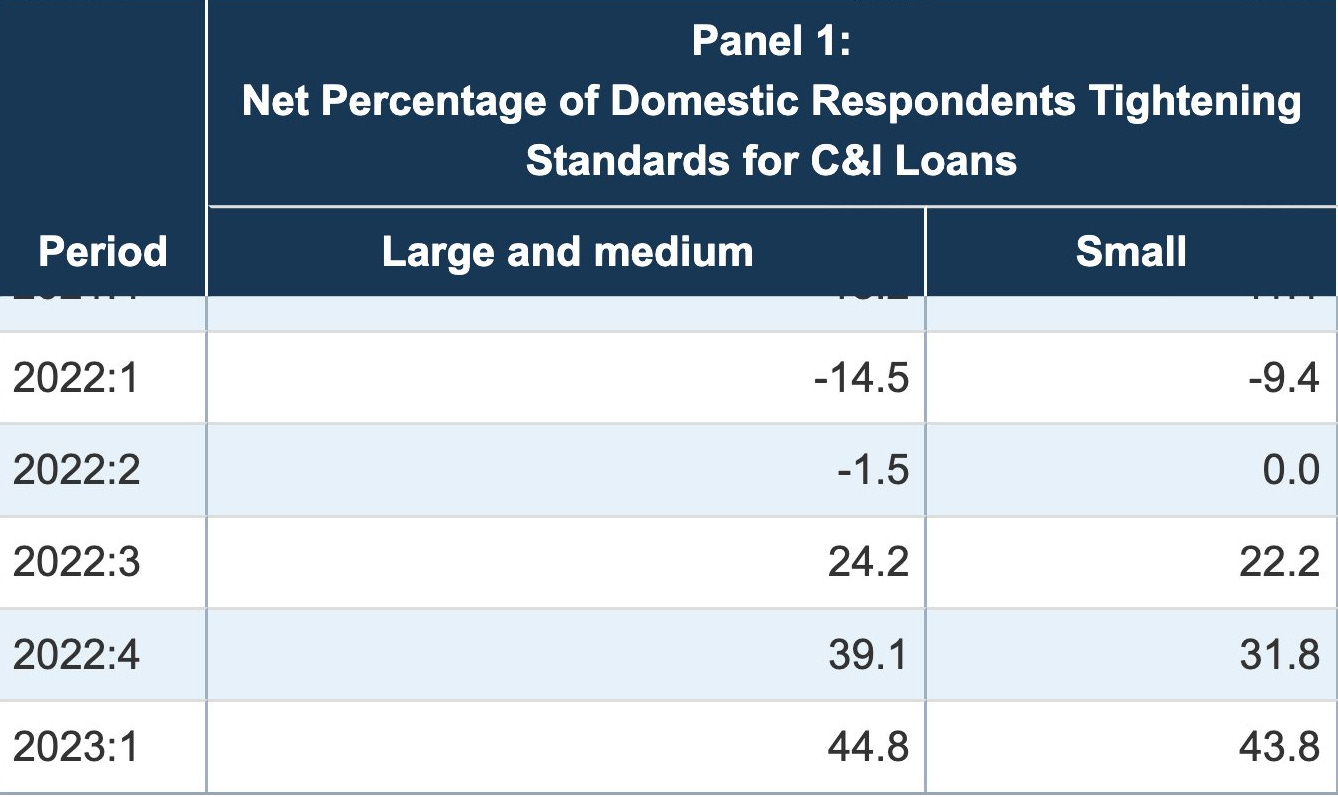

These companies, even if they enjoy consumer support, are beginning to see credit conditions deteriorate as a result of rising rates. Expectations of a slowdown in activity, caused by a longer than expected period of high interest rates, are making US banks more cautious about lending to businesses (C&I loans).

Nearly half of the banks report a tightening of credit to banks of all sizes. The tightening here is very clear. In just a few months, lending conditions have tightened significantly.

The risk of a slowdown does not concern household consumption in the short term, which, as we have seen, is benefiting from wage increases... but this time it is business investment that is at risk, as their conditions of access to credit are tightening.

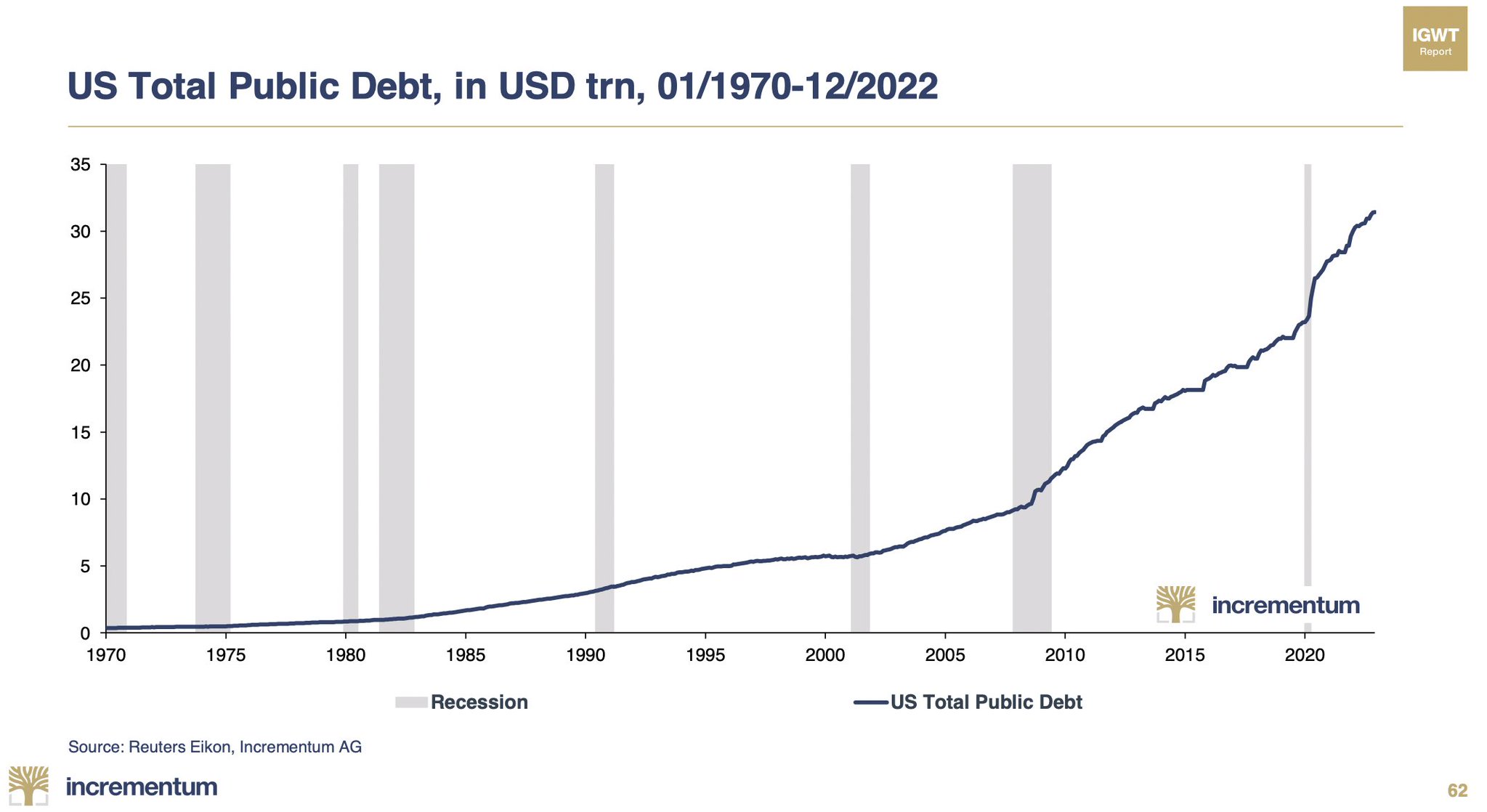

The other victim of this stalemate is the U.S. federal government, which is no longer able to finance its deficits as the rates at which it borrows to pay off its past debts rise. The higher the rates go, the more money is needed to pay off old loans. The federal government is in a dramatic situation because the costs of its repayments have increased dramatically. The US public debt has tripled since 2008:

We are experiencing a 2008 crisis in reverse.

In 2008, the risk came from the banks and spread to households and businesses. The government intervened to restore the stability of the entire system.

Today, the risk comes from the State. It is the government that has to ensure the survival of businesses through its stimulus plan and that has to assume a longer than expected period of rising interest rates. For the moment, the risk does not come from a possible consumer default. And this time, the banks are making a lot of money in this configuration...

In 2023, the main risk is the default of the sovereign state, since all credit risk is now transferred to it.

The government can default in two ways: either it asks its central bank to print the money needed to repay its debts, or it opts for an outright default and refuses to pay its creditors at current rates.

It is mainly this risk of default that is currently driving so many investors into physical gold.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.