The Kaplan scandal ought to be on the front pages of the newspapers: I cannot remember another case involving such an obvious abuse of the market on the part of someone so high-up in the institutions of the U.S. Federal Reserve...and coverage of all this in the media is extremely limited!

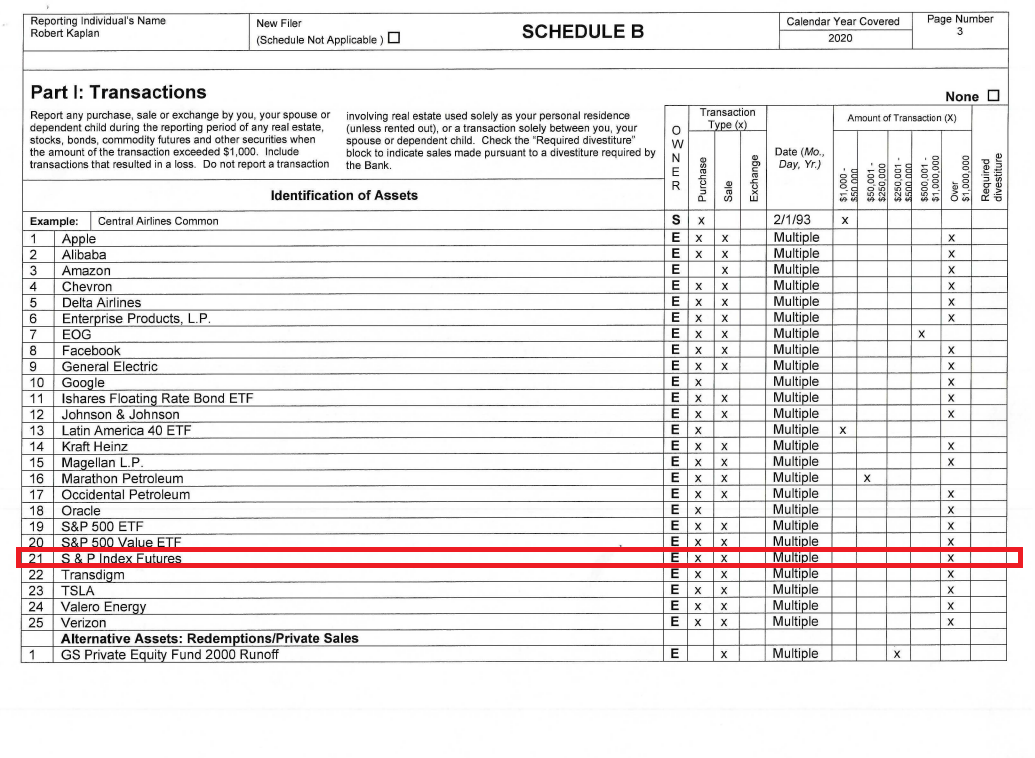

As a reminder: last week, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, Robert Kaplan, prompted a wave of indignation after the personal trades he made during the year 2020 were made public.

The case took on greater magnitude when the social medias (which are trying to play the role once played by investigative journalists) reported the notorious “disclosure”, the transaction statement that was published by Mr. Kaplan’s financial broker. The publishing of statements like this does not usually arouse the curiosity of the public, and Robert Kaplan himself must have been surprised by how much consternation was caused.

But there is one line in the statement that has left observers intrigued. It indicates that Mr. Kaplan negotiated futures contracts on the S&P 500 “multiple” times.

It should be noted that the E-mini S&P 500 (ES) future contract is a particularly useful product for investors who make their trades outside the opening hours of the markets, with a very significant leverage effect available.

Kaplan had access to information that was not made public in the context of his role on the board of the Fed, and this would have enabled him to take up a good position on products like this, at precisely the times when the markets were closed. The year 2020 offered configurations like this numerous times, particularly in March, when the Fed literally took the decision between two scheduled meetings to save the markets by launching a corporate bond purchasing program. This operation literally catapulted the stock market upwards, even as all the global stock indices were tumbling. The ability to access information like this, at a time of such volatility in the markets, is every trader’s dream!

Any person with inside knowledge who was able to place orders to buy futures contracts at the time of that famous intervention made enormous profits by taking advantage of the exceptional leverage effect of such instruments.

If this futures market was regulated by the AMF, Robert Kaplan’s trades would have unraveled and would likely have amounted to abuse of the market (more than just a simple violation, they amounted to the crime of insider trading). There would doubtless be sufficient cause to launch legal proceedings against the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas.

We are talking about a man, though, who is one of the major players in U.S. monetary policy, in a regulatory environment that is a long way away from the constraints imposed by the AMF, and it would be wrong to expect this case to result in Kaplan facing any accountability. What will live long in the memory about this episode is the fact that a junior French employee at an investment firm has more constraints imposed on him, when placing orders, than one of the directors of the Federal Reserve!

An interesting question arises: Has Mr. Kaplan taken a “short” position on the correction to the markets that we are currently experiencing? Since the time he promised he would sell his positions for “ethical” reasons, the market has been accelerating its correction...

Insiders at the Fed remain, without question, the best indicators for the markets’ ups and downs...

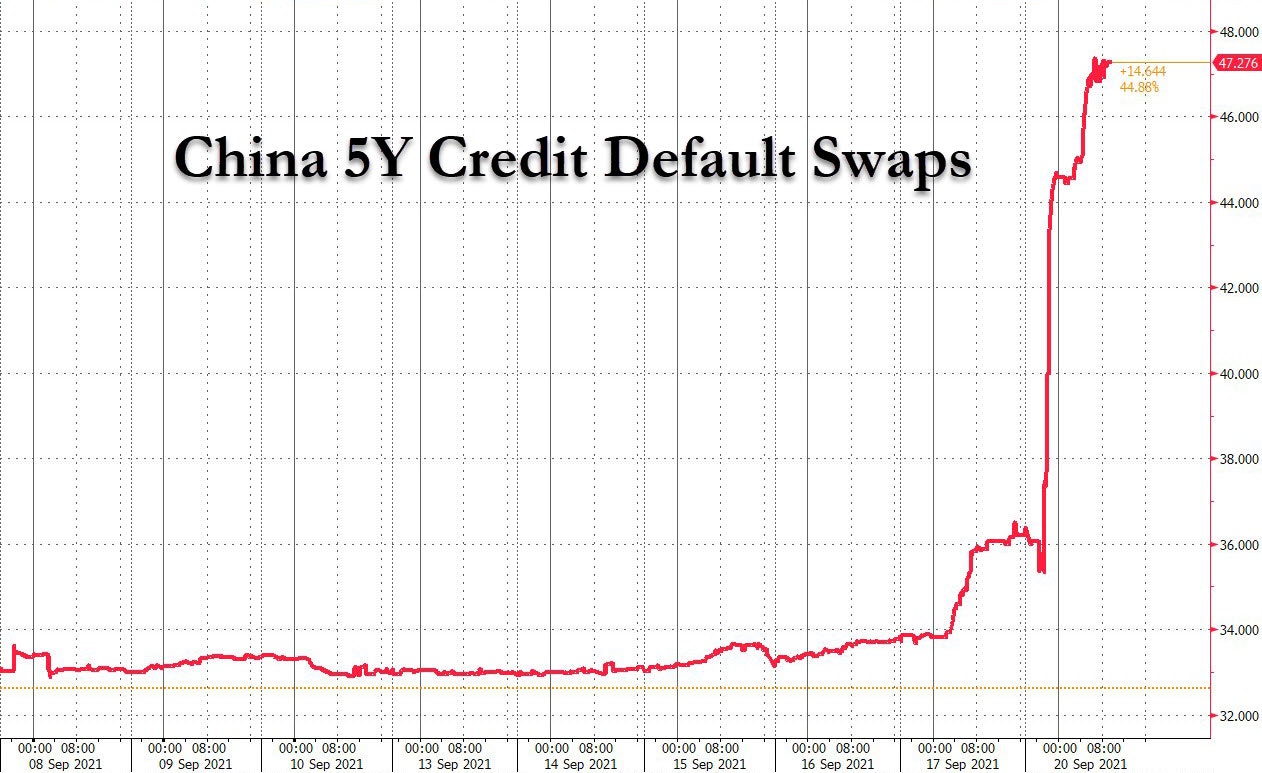

Markets that are having a tough time managing the threat of contagion from Evergrande, the bankrupt real estate giant, whose collapse is starting to have a knock-on effect along the entire Chinese stock market. The risk is even reaching the level of China’s CDS.

As observers wonder whether the collapse of the Ponzi scheme that Chinese real estate effectively constitutes will spread to the entire bonds market, it is important to remind people that, by contrast with the situation in 2008, there is a lot more liquidity in the financial system, and that the banking sector appears to be far more reliable than it was then. Every day, the Fed accepts more than $1.2 trillions in “reverse repo” operations, the mechanism by which numerous institutions exchange their surplus cash for treasury bonds, subject to remuneration on the part of the Fed. The crisis in 2008 took place against a backdrop of a lack of liquidity, but this time, the reverse is true, really: there is too much liquidity, and the central banks have inundated the financial actors, even though neither the rate at which bonds are being issued, nor the yields provided by these products, are managing to compensate for this avalanche of fresh money.

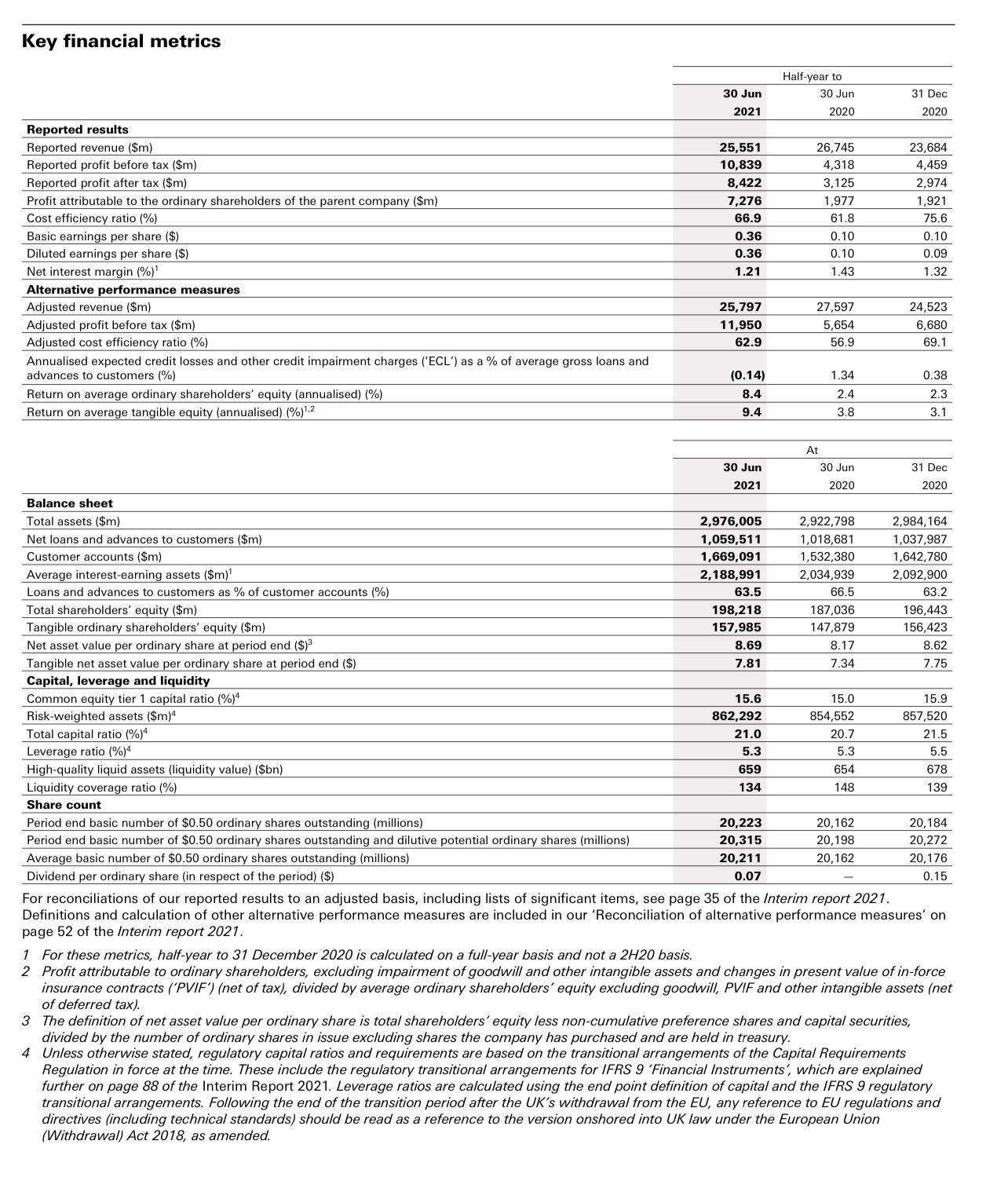

The banking sector is far more robust, as well. Especially in the United States. Europe is another matter. If we focus on the immediate risk, however, it is hard to find signs of imminent panic. When one looks at the latest results of HSBC, for instance - a bank that is in the front line in terms of facing the fallout from the collapse of Evergrande - it is difficult to imagine a brutal spreading of the contagion to the banking system at this stage: there is little leverage effect, and the solid loan-to-deposit ratio of almost 70% is quite capable of withstanding a major default.

It really would take a catastrophe for the Evergrande situation to trigger a banking crisis. Foreign investors hold 19 billion in debts that the company will likely never repay. That’s a lot of money, certainly...but the Fed is buying ten times more debt instruments every month, without the slightest scruple. China’s central bank was quick to take action Wednesday, moreover, by injecting just over $20 billion into its banking sector. What good would it have done, after all, to allow the fire to spread? There are, nonetheless, a fair few lingering questions (for the Chinese) in this affair, and the implications of default cascades should be monitored.

There are far more worrying things going on than the Evergrande affair, however.

Chinese real estate accounts for 20% of the country’s economy. U.S. consumption accounts for 70% of its economy. The engine for this essential component of our global economic system is at risk of a breakdown, because the consequences of inflation are in the process of taking hold over the entire production chain. In my opinion, this is the biggest threat we face.

Since the Evergrande situation started being on everyone’s lips, the U.S. small capitalizations market has corrected itself more than all of the emerging markets, and this would not be the case if the Chinese contagion were the sole source of the correction.

That does not mean that the collapse of an entire sector of the Chinese economy poses no risks of contagion at all.

But there is a problem that is even more serious, because it is more difficult to contain.

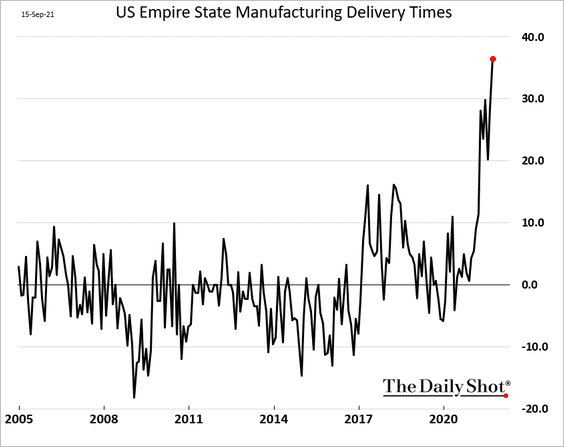

The latest figures on US Empire State Manufacturing Delivery Times are soaring to levels never seen in recent years:

Delivery times are getting longer, global trade is getting jammed up.

This is starting to have direct repercussions on certain companies’ results.

The U.S. company FedEx has just published some very disappointing figures: its operating profits for the first quarter of the year were negatively affected by a hike in costs estimated at 450 million dollars year on year, due to three things:

1. A sluggish labor market, leading to inefficiencies in the market

2. Higher wages

3. A hike in the costs of the services purchased

Each of these aspects has one common denominator: inflation.

Service providers are suffering from rises in costs. This phenomenon is accelerating, and what’s more, it is spreading to all service activities, across the globe.

Wages are going up, and that’s bad news for anyone who thought the inflation would be transitory. A rise in wages is rarely transitory.

Today, however, the major problem is firms’ inability to mobilize a suitable labor force, in sufficient numbers. The bad capital allocations of the last few years are the consequences of the monetary and fiscal policy of our dear friends, the central bankers. The monetary creation has been accompanied by a poor distribution of capital: less engineering, less training, less investment in areas where it was so badly needed, more financial operations (stock buybacks and so on), more speculating...on the part of companies that ‘over-financialized’ themselves amid the euphoria of this unprecedented period when money is free. It is a classic phenomenon that one sees whenever there is uncontrolled monetary expansion. When the printing machines are put into overdrive, the bad money chases the good money!

The bad news is that we have reached the end of the cycle. The consequences of this monetary inflation are now spreading to the real economy, and the phenomenon is increasingly out of control.

This time, neither the Fed nor any of the central banks can do anything about it. One can’t print the employees that FedEx needs in order to ship the Christmas presents people would like to order online, but that are increasingly becoming “unavailable”. And one can’t print additional cargos that can somehow avoid the ports that are now clogged up.

Even if one were to print money and give it away for free in order to prop up consumption, it would be impossible to avoid the consequences, which are now clearly visible, of the inflation created by this monetary madness. The difficulties at the level of the production chain brought about by this inflation are now squeezing companies’ margins, and that is what FedEx’s results show us.

In response, the carrier decided to introduce an unprecedented rise in its rates to try to save its margins. This will be the path chosen by numerous companies caught in the same trap: try to push back against the squeezing of margins by increasing the prices paid by the end customer...and this will have an effect both on consumer prices and on the upcoming figures for inflation expectations.

This environment is, of course, a direct threat for consumption. Faced with a shock such as this, with price rises passed on directly to the consumer and with delivery times getting longer and shortages appearing, the engine is at risk of quite simply failing.

In such a context, the Fed’s mission, as it seeks to stave off fuel exhaustion, appears increasingly complicated.

This risk has not as yet been truly measured by the market: a close eye will nonetheless need to be kept on the warnings from companies in the sectors concerned, and the spread of the falls in stocks will need to be measured.

In the market that interests us, namely that of precious metals, we have seen this week that gold is retaining its safe haven faced with the violent correction of stocks. Gold is still supported by a very intense physical demand, and the closeouts of paper contracts in the margin calls are producing entry points that are only reinforcing these purchases of physical gold.

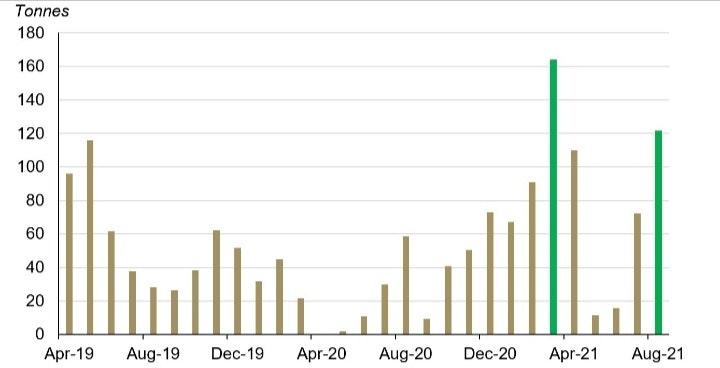

Imports of physical gold from India are continuing to be robust in the month of August:

The premiums on physical silver are also up since last week, and this indicates that the ‘paper’ market will have a hard time pulling the spot price down in any significant way.

This has become a classic situation: the algorithms that control the prices of precious metals react in a very volatile manner in the periods when the Fed announces decisions about its rates policy.

This volatility offers unique investment opportunities for the protection of our savings, which are at risk of being greatly affected by this new inflationary period and the economic shock it is going to provoke.

Original source: RechercheBay

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.