All of the models presented predicted that the recession would hit in the U.S. by the end of last year, but it still hasn't happened.

One model, Nordea, continues to forecast a decline in US GDP. This model is now well insulated from the current consensus that anticipates a slowdown in 2023, but not a recession.

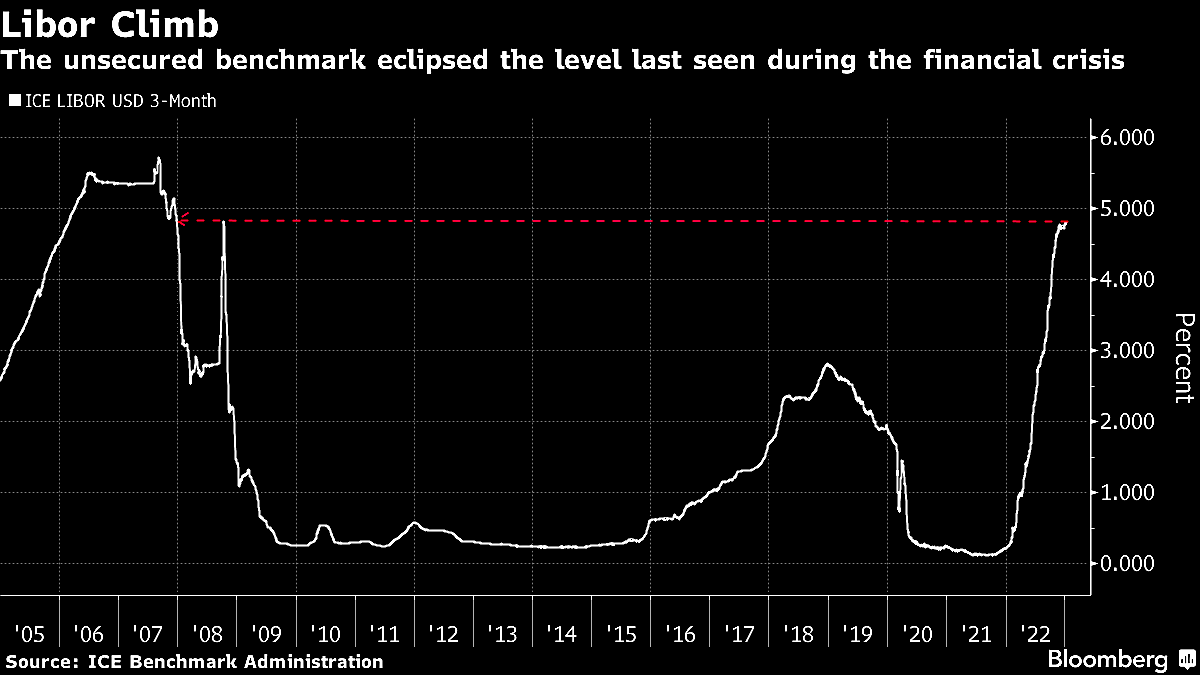

Analysts who were expecting a recession also pointed to the new excess stress in interbank liquidity.

A Bloomberg article states that the pressure on the LIBOR rate has reached a new high since 2008, signaling liquidity stress in the interbank market:

However, this reasoning should be taken with a grain of salt.

The conditions to access liquidity were not the same in 2008, and analysts who look to this indicator for warning signs in the banking sector may not have all the facts in hand: the tool that revealed a flaw in 2007 may not be as relevant in 2023.

If the results of the last few quarters are anything to go by, the US banks are far from showing any signs of alarm. Basically, there is nothing in their figures to suggest a recession. In fact, the opposite is true: when you see a bank like US Bancorp publishing such good results in the last quarter of 2022, it is hard to imagine a short-term disaster scenario for the US banking sector.

Despite the widespread talk of an impending recession, facts are now taking precedence over narrative, producing nice short squeezes on some US banking stocks. US Bancorp has rebounded sharply since the beginning of the year, with significant volume.

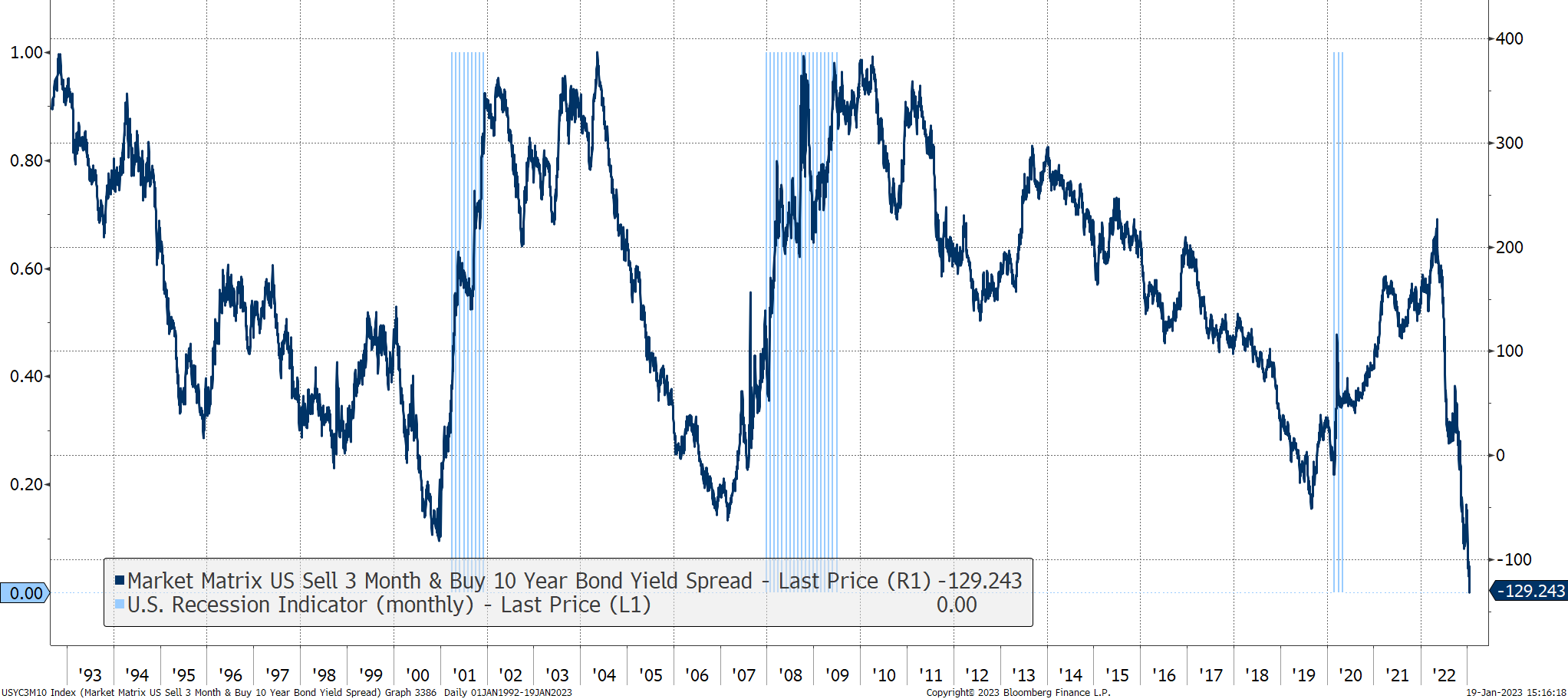

Those predicting a short-term recession are relying on signals of an inverted yield curve and the logical consequences of the decline in activity caused by the energy crisis in Europe.

The yield curve is the most inverted it has been in the U.S. in thirty years:

And for the past thirty years, every time there has been a sharp reversal of this type, an equally sharp recession has started in the following months.

What is going on? Why is the recession predicted by these models still not showing up?

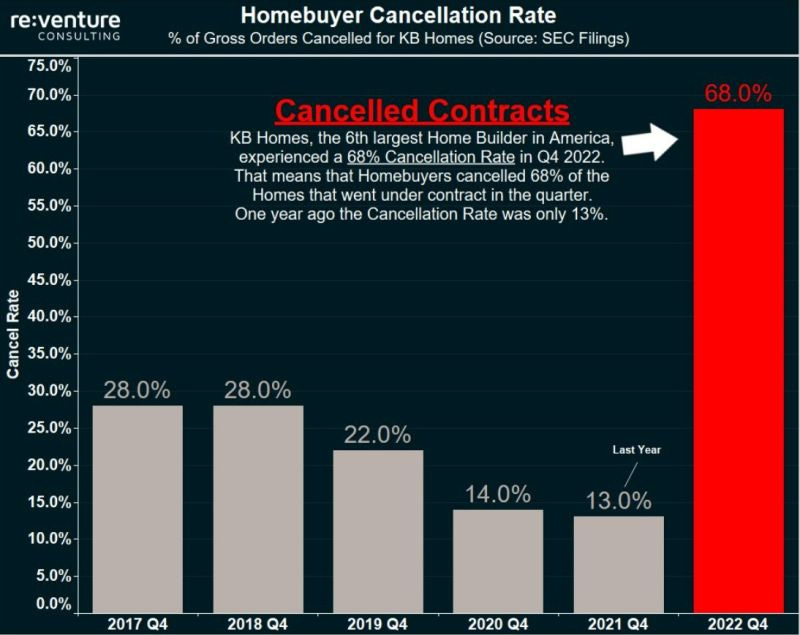

Yet the real estate sector is at a standstill, as we saw in my second article of the year.

The homebuyer cancellation rate is at an all-time high in the United States. For example, KB Homes reports a 68% cancellation rate on its latest sales. Last year at this time, the rate was 13%.

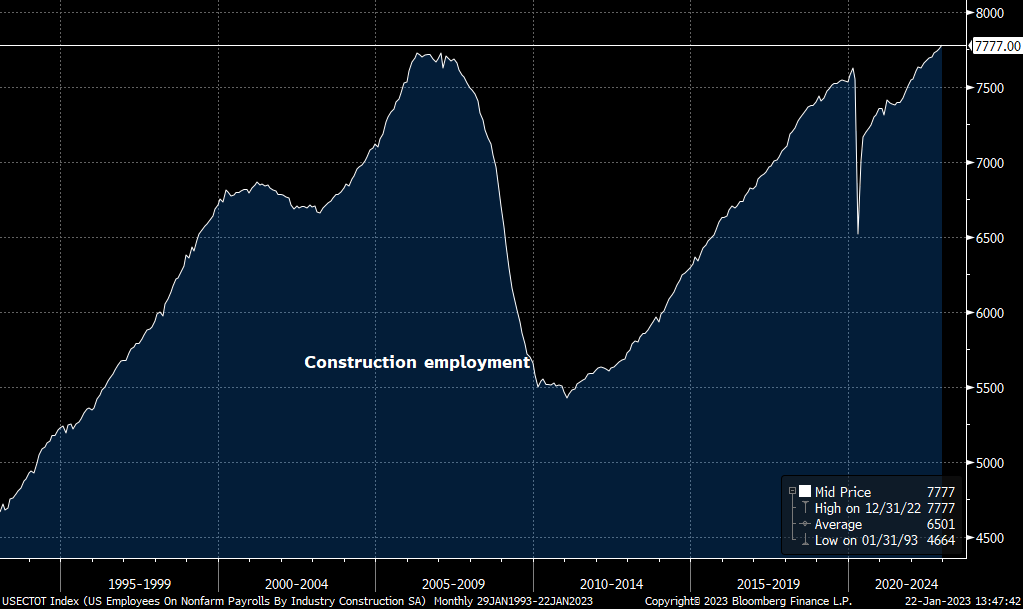

While the real estate sector has run out of steam, strangely enough, the construction sector continues to do well. The decline in real estate activity is causing a slowdown in construction activity, but unlike 2007, this decline in activity is not accompanied by layoffs in the construction sector, at least for the time being.

Employment levels in this sector are even continuing to break records!

How can this paradox be explained? Why is the decline in activity not leading to layoffs?

Despite the downturn in real estate, industry players are holding on to their employees, probably because they know the job market is very tight and that the Biden administration's infrastructure investment plan will create strong demand in the coming months. It is better to keep qualified and motivated human capital on hand than to risk missing out on this year's public investment projects because of a lack of personnel. The fear of "job switcher", which drives up the price of a work position and which I mentioned in a previous article, is also to be taken into account in this disconnection between the real estate figures and those of employment in construction.

The recession is being postponed as government spending is about to replace private spending in the US. The huge $1 trillion infrastructure investment plan passed in August 2021 is capable of reviving the construction sector. Without this plan, the sector would have already lost hundreds of thousands of jobs and the U.S. recession would likely be well underway.

When we look at business forecasts, we forget the radical change that this post-Covid period has brought about in public spending. In France, we are familiar with Emmanuel Macron's "Whatever it takes", which has shifted a large part of the cost of the crisis onto the shoulders of future generations by creating new public debt. The French government has also preferred to increase this public debt to alleviate the impact of inflation on French households.

This reflex is not a French specialty. The German government has also chosen to increase its debt by freezing the price of energy for individuals and companies. The idea of creating public debt to support the private sector is spreading around the world. In California, the numbers are even more impressive. In this state, the accounts have gone into the red in only ten months (from a profit of +25 billion to a deficit of -100 billion) after a record public spending program. The State of California is going into debt to support the effects of inflation, while at the same time revenues are collapsing due to the real estate crash. One of the richest states in the country is now in a budgetary bind and running an unprecedented deficit.

And what is happening in California is likely to happen on a larger scale.

With rising interest rates, states that have increased their debt are forced to incur more expenses to pay down more and more debt at a time when tax revenues are declining. And on top of that, these states are now being asked to relieve economic activity in the face of slowing private demand.

The equation is becoming impossible and this is reflected in the monthly budget deficit figures.

U.S. tax revenues, at $455 billion, were down 6.5% in December compared to the same month last year.

U.S. spending for the same period was up 6.3% to $540 billion.

The country is no longer able to maintain its course, the deficit is widening at a record pace and shows -$85 billion in a single month. It was -$21 billion last year.

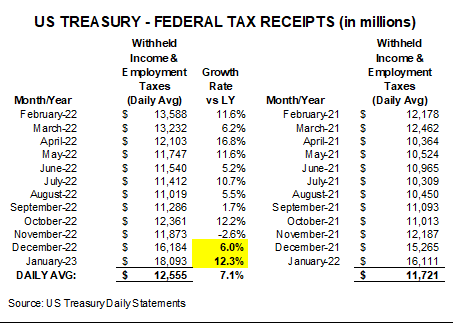

These bad numbers come at a time when payroll tax revenues are rising.

Despite the positive effect of inflation on these payroll tax receipts, the amount the government has to pay to pay down its debts and for its public spending programs is far too high for these inflationary revenue increases to affect the overall figure: the United States is in a budgetary bind.

In this impasse, there are unfortunately not many choices left.

Turning back would trigger the recession that the country has avoided so far, precisely in anticipation of this policy action.

Continuing in this impasse leads us to the great wall of debt.

The presence of this wall is the primary reason to invest in physical gold. Gold is now the only protection against the damage of a collision with the debt wall.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.