The global economy is facing a series of growing risks, such as financial market volatility, currency imbalances and economic tensions.

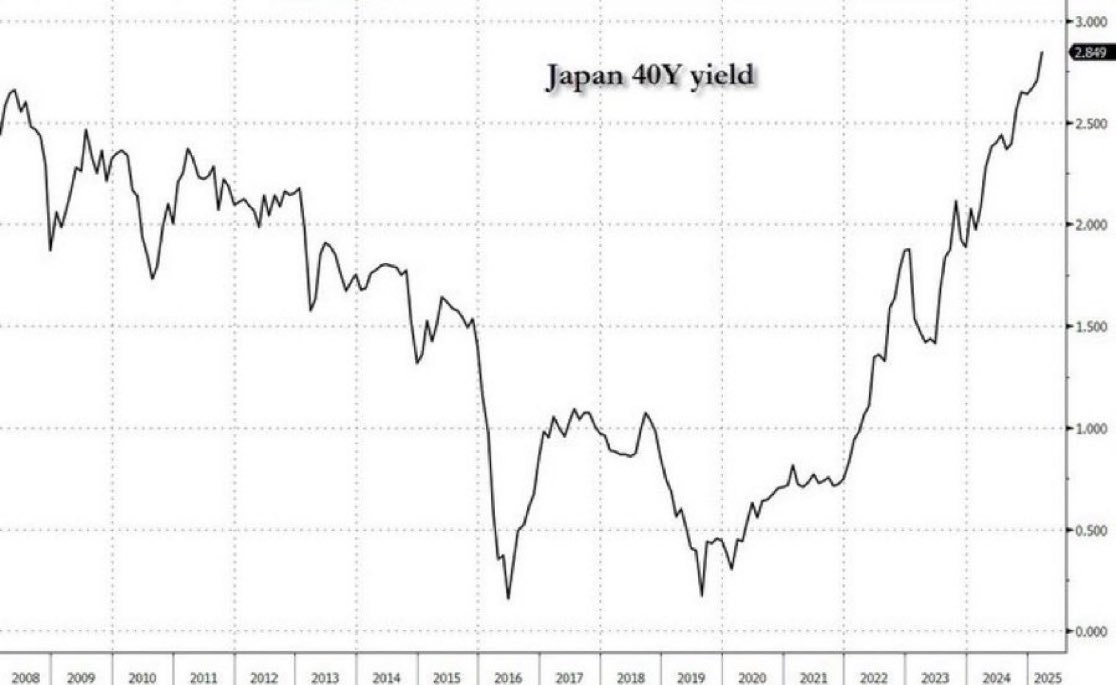

Last week's bond crash finally spread to Japan this week.

What was initially just a shock on Western bond markets - characterized by soaring yields and capital flight - has now crossed the Pacific. Despite its reputation as a bastion of stability thanks to ultra-accommodative monetary policy, Japan was not spared the contagion.

Japanese bond yields (JGBs) have surged, putting pressure on the Bank of Japan, already forced to intervene more and more frequently to contain volatility. This phenomenon illustrates a broader trend: the global sovereign debt market is faltering under the impact of restrictive monetary policies and an increasingly abundant bond supply.

In other words, bond shocks are no longer compartmentalized - they are becoming global.

Yields on 40-year Japanese bonds are reaching record levels, driven by the global sell-off in sovereign debt, expectations of rate hikes by the BoJ, persistent inflation (4% in January 2025) and a yen that is still too weak:

With domestic demand sluggish and the BoJ relaxing its control of the yield curve, the Japanese market is gradually emerging from the era of ultra-low rates. This trend is increasing the cost of borrowing, at a time when the country is facing a colossal debt burden.

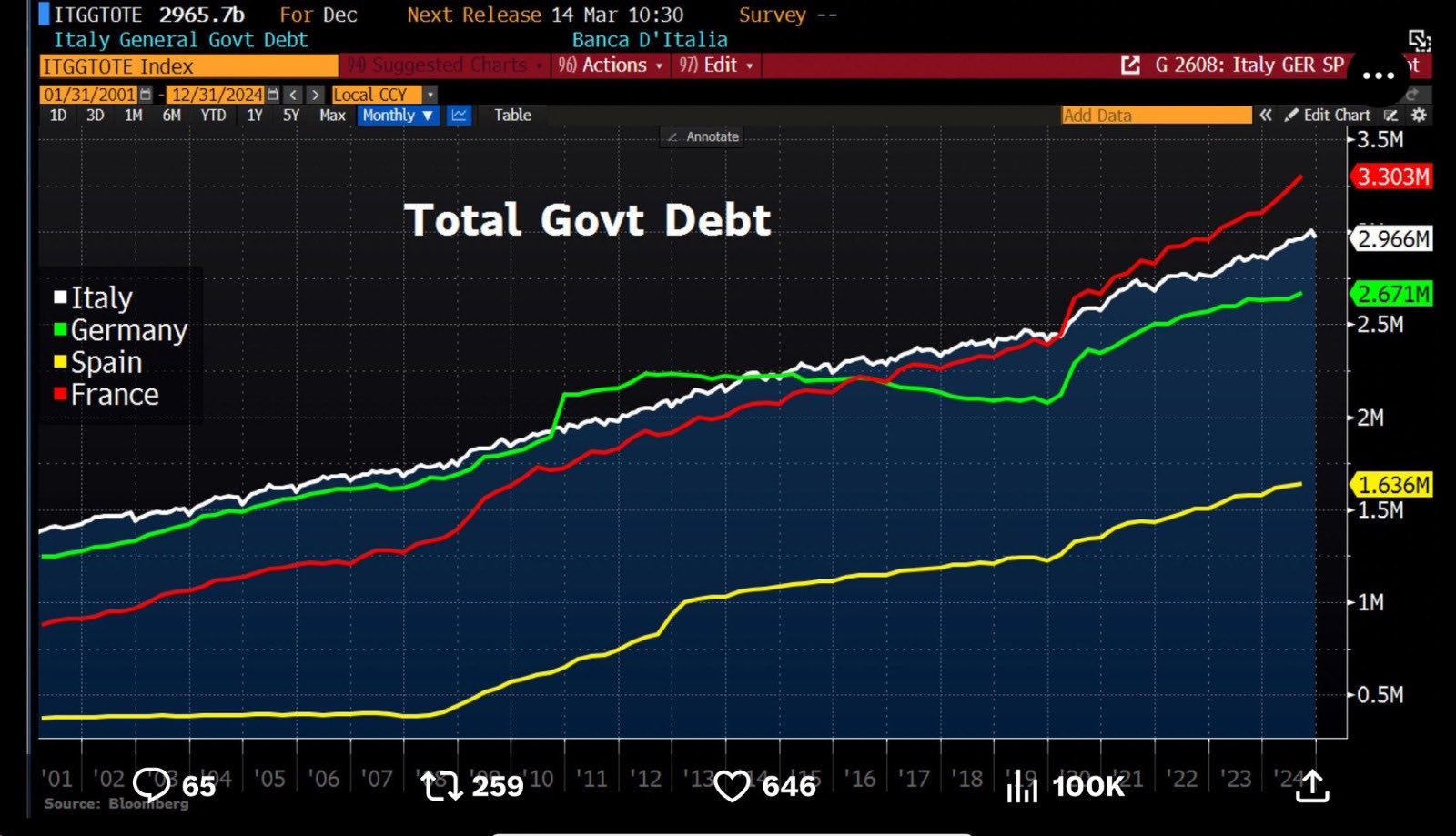

This trend could spread to Europe, where rising Japanese yields could encourage Japanese capital to stay at home, reducing demand for European bonds and exerting upward pressure on their yields.

This would weigh on equities and reduce liquidity, at a time when European debts are reaching unprecedented levels:

In the US, the dynamic could be even more pronounced: a reverse carry trade (Japanese investors selling Treasuries to repatriate their funds) would push US yields higher, increasing the cost of credit and weakening equity markets.

The carry trade has been a key driving force behind the rise in US markets - reversing it would have the opposite effect.

For years, Japanese investors, along with other global players, borrowed at ultra-low yen rates to invest in higher-yielding assets, notably US bonds and equities. This movement supported the valuation of US markets, boosted liquidity and kept bond yields low.

But with Japanese interest rates rising and the yen still weak, this carry trade is becoming less attractive. If Japanese investors start selling their dollar-denominated assets to repatriate their capital, this could trigger a series of cascading effects:

- Rising US bond yields: less foreign demand for Treasuries means higher rates.

- Pressure on US equities: a rise in rates would weigh on the valuation of equities, particularly technology and growth stocks.

- Global restructuring of capital flows: a stronger yen would force a redistribution of investments, with effects not only in the USA, but also in Europe and emerging markets.

In other words, what has been a powerful tailwind for the markets could turn into a brutal headwind.

Concerns are now turning mainly to the Japanese financial system and its potential impact on the rest of the world.

One of the main areas of concern for analysts at the moment is the situation of Japanese bank Noren Chukin, which could be at the root of a global financial crisis. Although this institution is still little known to the general public, it is particularly exposed to the carry trade, a strategy in which investors borrow at low cost in yen to invest in more remunerative assets, such as US bonds. With the yen's recent fall below the critical 150 JPY/USD mark, this strategy is becoming increasingly risky. Rising financing costs are jeopardizing the banks and funds that have massively used this method. If investors are forced to liquidate their positions, this could trigger a wave of massive selling, creating a domino effect on Western financial markets.

The US bond market is also under pressure, with a colossal volume of debt to be refinanced by 2025. If interest rates remain high, the cost of refinancing could explode, forcing investors to sell their bonds en masse. This would trigger a spike in bond yields, increased instability and, potentially, a liquidity crisis similar to that seen in 2022 on the UK gilt market.

In contrast to previous corrections, US Treasuries did not play their safe-haven role this time, reflecting the current tension in this asset class.

Traditionally, in times of market turbulence, investors flock to US sovereign debt, driving yields down and bond prices up. This time, however, the pattern broke down: Treasuries fell in tandem with equities, instead of serving as a haven of stability.

Why did this happen? Because the dynamics have changed. With public debt soaring, inflation persisting and the Federal Reserve forced to keep rates high, investors are beginning to doubt the reliability of the bond market as a defensive asset. The traditional “equities down, bonds up” relationship no longer works when the systemic risk comes directly from the debt itself.

In other words, when the crisis originates in bonds, they can no longer act as a safe haven.

The collapse of bonds proves that public debt is no longer defensive.

When governments go on a spending spree, they build up uncontrollable debt. The result is excessive expansion of the money supply, which fuels persistent inflation. As this dynamic takes hold, the perception of sovereign debt as a safe-haven asset is eroding.

What was once a pillar of stability is now becoming a factor of instability. The more governments take on unlimited debt, the more they undermine the bond markets that are supposed to embody prudence and resilience. "Sovereign security” is no more than a mirage, dissipating under the weight of fiscal irresponsibility.

At the same time, the US housing market is showing more serious signs of distress than in 2008. Mortgage defaults are on the rise, exceeding even the levels seen during the global financial crisis. The situation is exacerbated by a number of factors: record-high property prices, making buying a home unaffordable for a majority of Americans; mortgage rates at levels not seen in 25 years, increasing the cost of borrowing; an explosion in maintenance costs, property taxes and insurance due to inflation; and a collapse in the commercial real estate market, marked by empty offices and plummeting rents. If the crisis intensifies, it could lead to the bankruptcy of several banks exposed to the real estate sector, exacerbating the fragility of the global financial system.

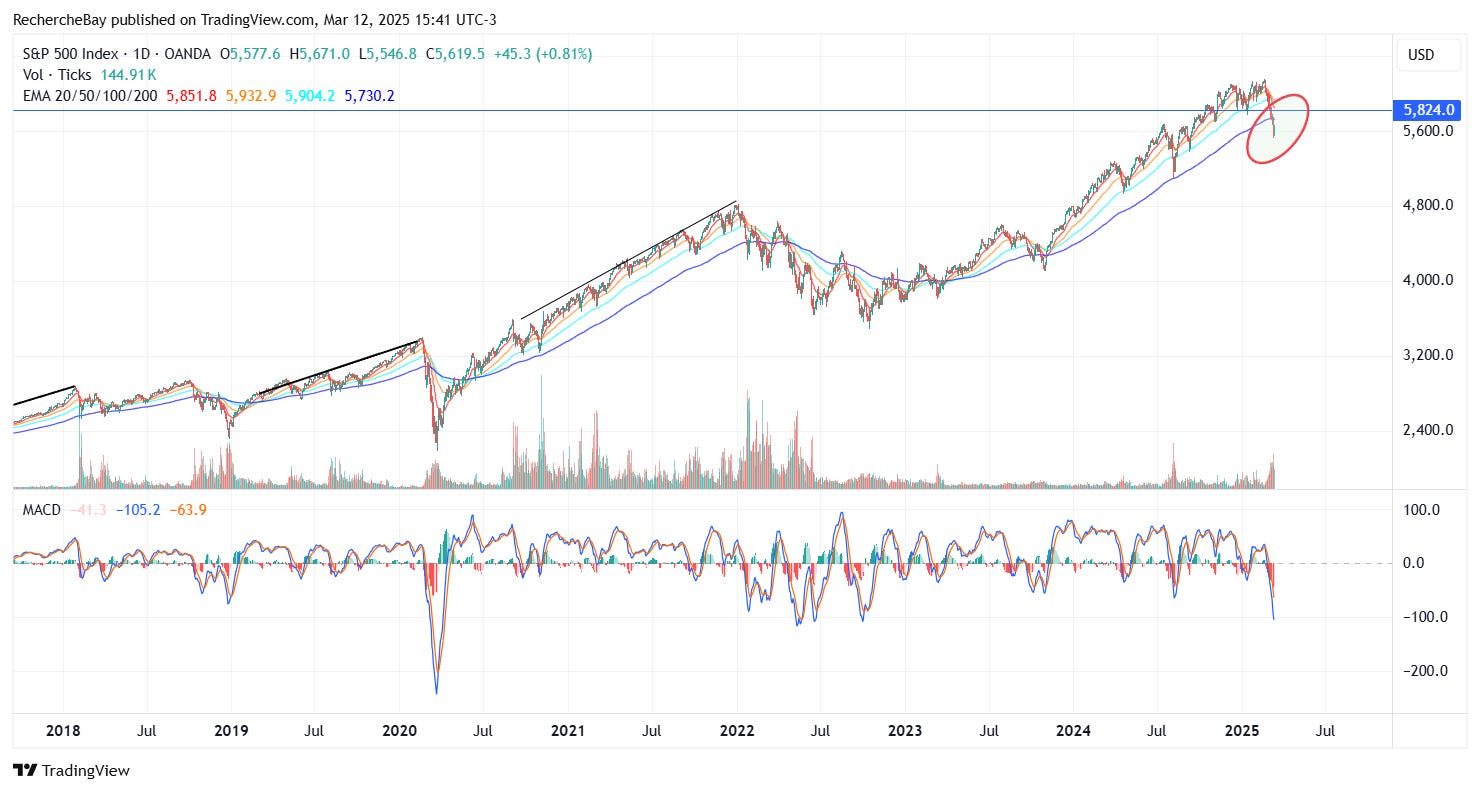

Stock markets, especially the technology stocks of the Magnificent 7 (Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, etc.), are overvalued and highly sensitive to economic fluctuations. Even a small withdrawal by some major investors could trigger a spiral of selling and trigger a stock market crash.

SPY on the verge of breaking through the mythical 200-day moving average...

When market capitalization exceeds 200% of GDP, markets no longer simply reflect the economy, they become the economy.

In other words, a fall in the equity markets - whatever the cause - will inevitably drag the real economy into recession in such a financialized world. It's not the economy that causes the markets to fall, but the reverse: the stock market contraction spreads to the underlying economy.

Financial markets, economic imbalances and geopolitical tensions are converging towards a major systemic risk. The question is no longer whether a crisis will occur, but rather when and in what form. A stock market crash, a bond market implosion or a major bank failure could be the trigger for a global shock.

The current gold rush comes at a time when the global credit bubble is threatening to burst.

With unprecedented levels of debt and rising interest rates undermining bond markets, confidence in sovereign debt - once seen as the ultimate safe haven - is eroding. Soaring yields are putting pressure on governments, businesses and households, exacerbating fears of a liquidity crisis.

In the face of this systemic risk, physical gold is once again the safe-haven asset par excellence. Unlike bonds, whose value plummets with rising interest rates, and currencies, which are subject to past expansionary monetary policies, gold is not dependent on any single issuer and is not exposed to counterparty risk.

The rush to the yellow metal thus reflects a loss of confidence in the foundations of the current financial system, exacerbated by the inability of central banks to curb inflation without causing a shock to the credit market. If the credit bubble bursts, demand for gold could intensify further, propelling its price to new heights.

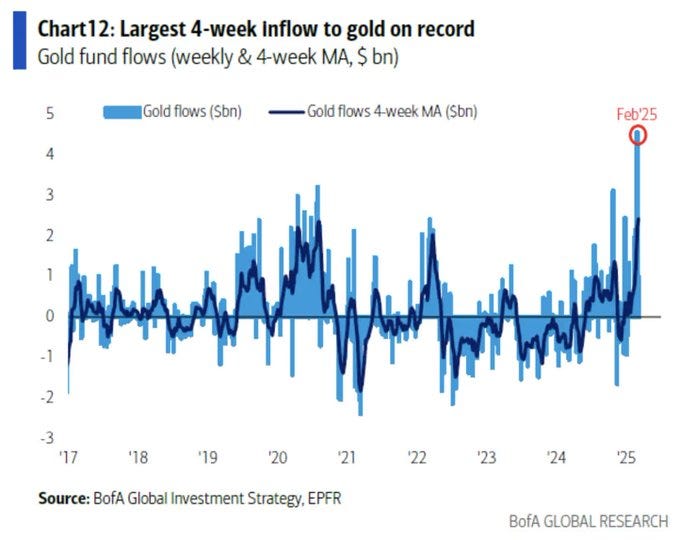

This week, gold funds reached unprecedented levels of outstandings:

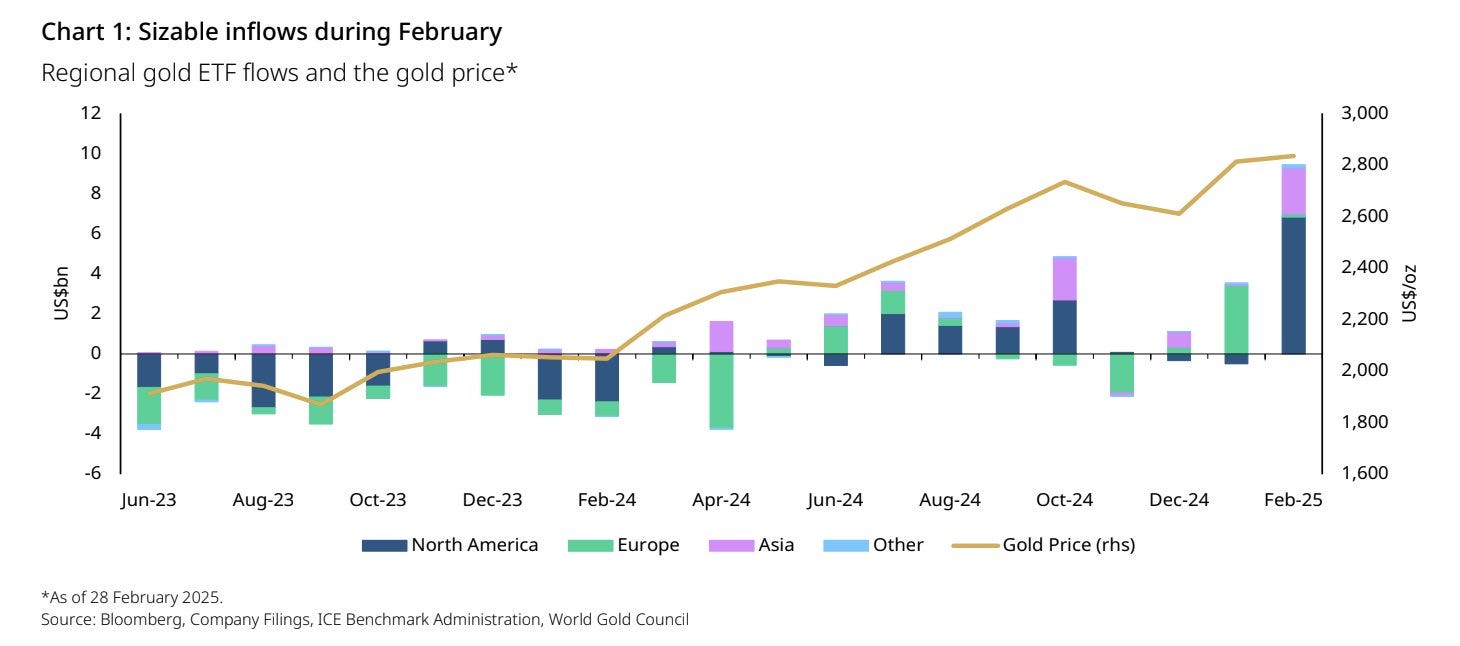

Gold-backed ETFs have seen an explosion in demand in the USA and China, while Europe seems to be surprisingly behind in this rush for the precious metal:

But the hot news isn't limited to gold - silver is also at the center of all tensions.

Silver stocks in London have reached critical levels, raising questions about the market's ability to meet growing demand. Pressure is mounting as physical supply dwindles, potentially leading to explosive price movements and heightened volatility.

This situation merits in-depth analysis. I'm preparing a special bulletin for you next week to decipher this impending crisis.

We'll be back to you very soon - so get ready!

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.