On Wednesday night, the U.S. central bank raised its key interest rate by 0.25%, triggering a lot of volatility.

As the markets try to gauge the impact of this new monetary tightening on the economy, let's try to stay away from the hubbub that traditionally follows Fed announcements. This week, we will instead focus on an element that is ignored by most analysts, but which is nonetheless essential for understanding whether inflation will pick up in the coming months: the level of metal inventories.

Regardless of the extent of the economic slowdown, and the extent of future demand, metal supply is being revised downwards in most markets. Forecasts for 2023 suggest that inventory levels will not follow the usual intrinsic demand cycle. Indeed, we are already seeing real "runs" in some markets as participants seek to secure future supplies in anticipation of shortages predicted by some analysts as early as 2023.

Let's start with copper.

The situation in Peru is getting worse every week. The social unrest is seizing the whole mining production of the country. The Chinese operator MMG has just announced the closure of its mine of Las Bambas "for maintenance", which represents more than 1% of the world production of copper. The Constancia, Antapaccay and Tintaya mines are now likely to suffer the same fate in the coming days, particularly because of the logistical and social disruption affecting transport and the entire Peruvian economy.

In the neighboring country of Chile, the government-owned company Codelco, the largest copper producer in the world, has announced a drop in production of about 10% in 2022 compared to last year.

Available copper reserves for the year 2023 are still declining.

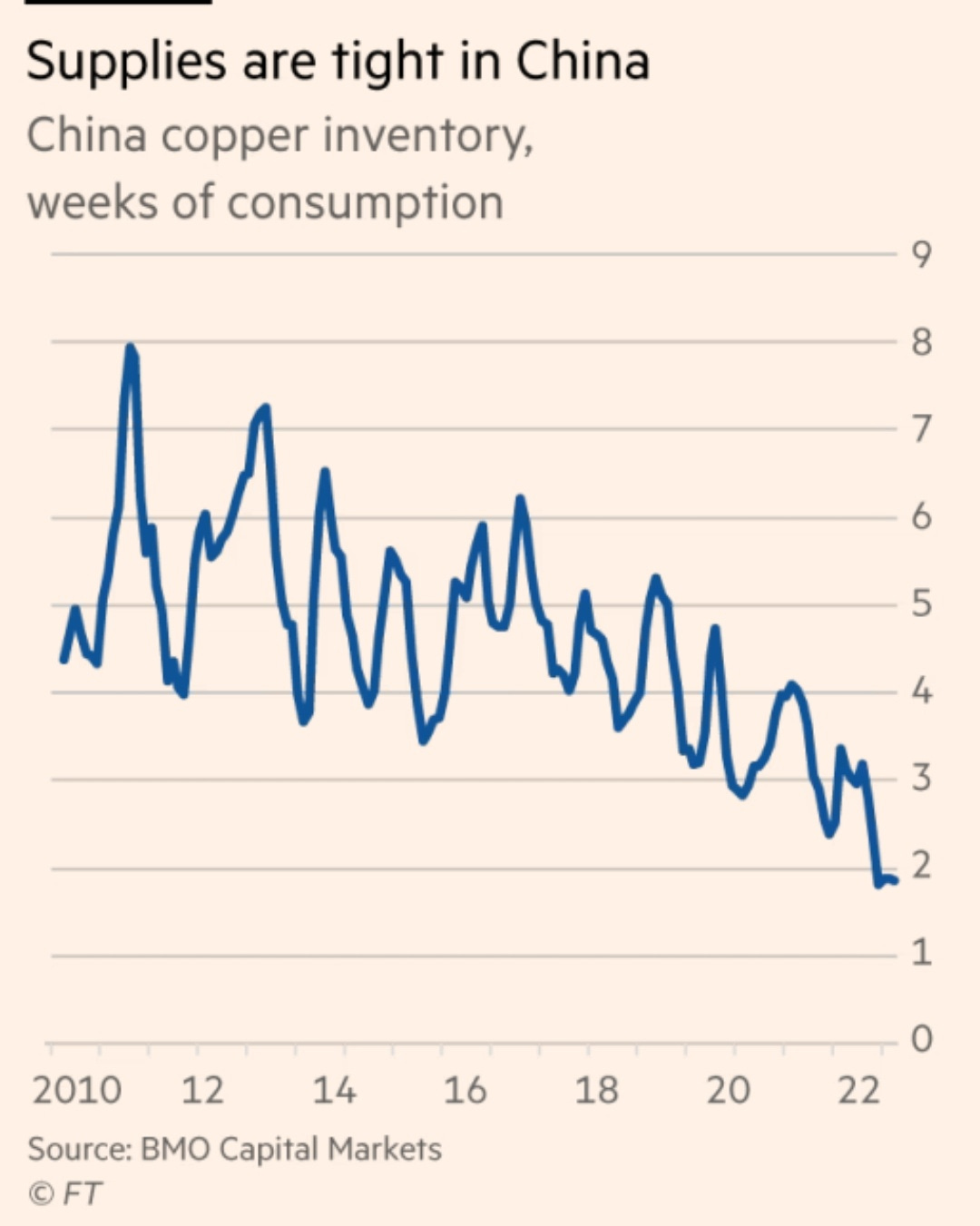

This decline comes at a time when Chinese inventories are at an all-time low:

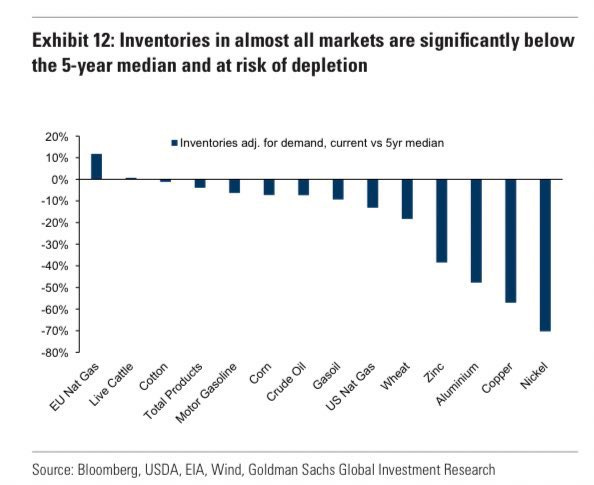

Copper is one of the metals with the highest risk of stock-outs in the short term:

Generally speaking, the available metals inventories on the London Metals Exchange have never been so low...

According to an article written by Mark Burton, the London Metal Exchange (LME) enters 2023 with inventories at their lowest level in at least 25 years, which could lead to future price spikes if demand proves stronger than expected. Inventories of the six major metals traded on the LME fell by two-thirds in 2022, with aluminum down 72% and zinc down 90%.

But let's get back to that special metal, copper.

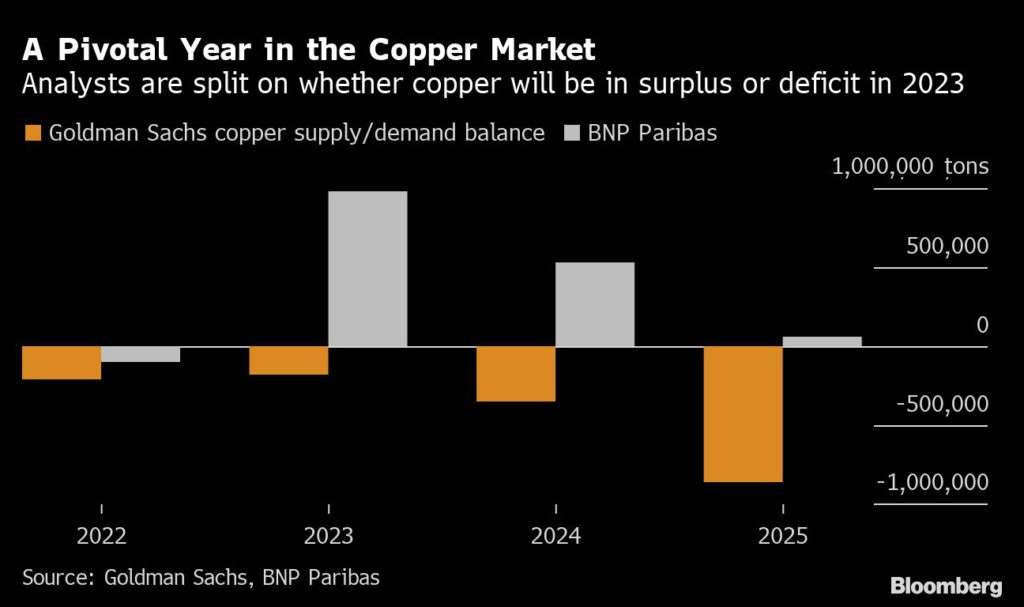

Analysts at Goldman Sachs expect a deficit as early as 2023, with the shortage accelerating in 2024. Conversely, BNP analysts believe that there will be ample supplies over the next three years:

This divergence between the two analyses is quite remarkable. It is a reflection of the total uncertainty in which we are currently navigating in terms of economic forecasting. The interventions of central banks have broken the classical analysis tools, and the models that used to be able to predict the timing of recessions no longer work. Interventions are so numerous, intense and uncoordinated that it has become very difficult to link economic data to a market movement.

For the copper market, one must compare two opposing movements and consider their potential for acceleration.

Will the announced economic slowdown be enough to slow the decline in copper inventories?

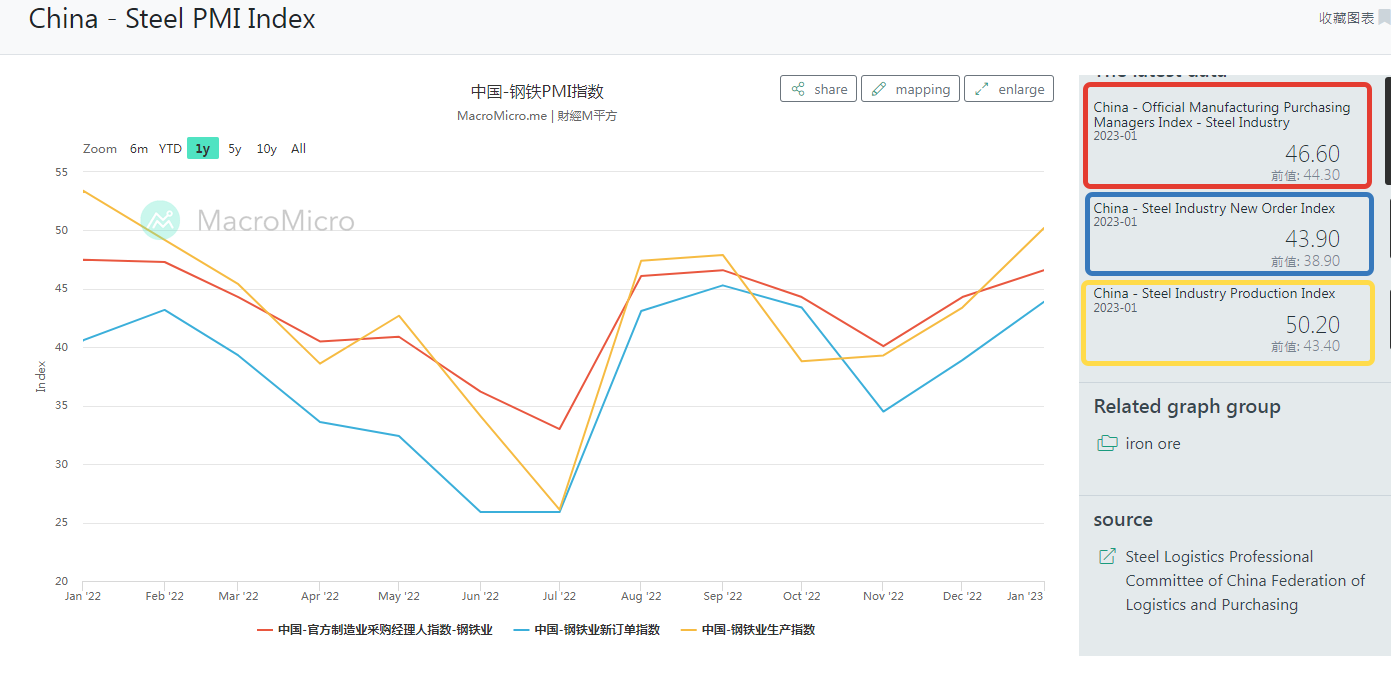

In China, the end of Covid has boosted demand for ferrous metals. Steel indicators (especially new orders) are once again trending upwards in this period of deconfinement:

Any continuation of this economic rebound will have a direct impact on the price of copper, as with such low inventory levels, the futures market will become increasingly sensitive to the slightest delivery demand.

To calm the rise in copper prices would require a fairly sharp entry into a recession. A simple global slowdown will probably not be enough to calm the metals fever in the short term, especially since the stimulus packages are likely to jeopardize expectations of a halt in copper demand.

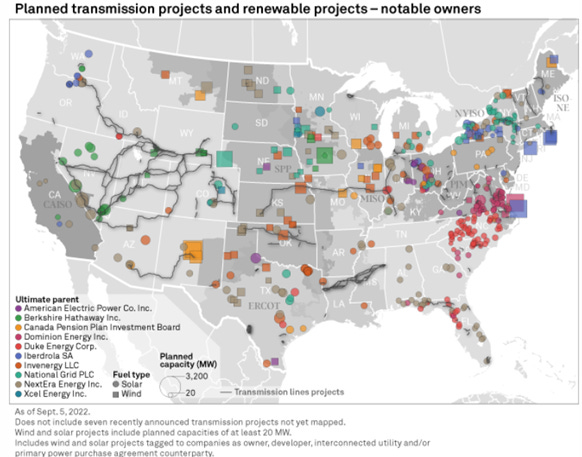

Little is known in Europe, but the United States has embarked on a vast renewable energy equipment project. Coupled with a significant effort to modernize the electrical grid, this investment project alone will be responsible for an increase in demand of several million tons of copper in the very short term...

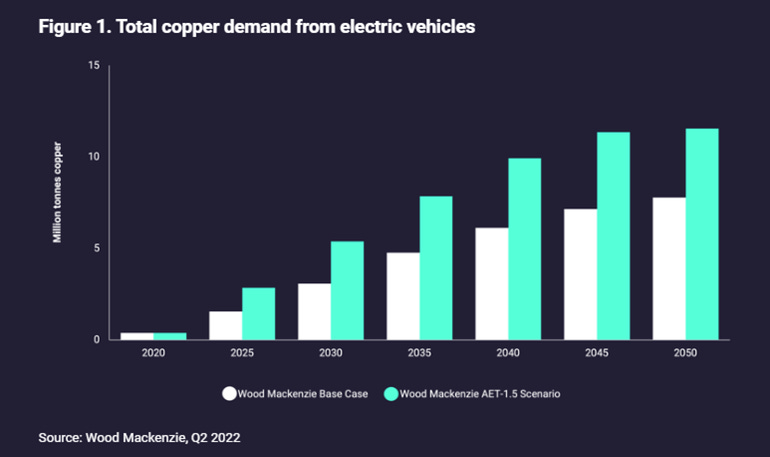

In addition to these needs related to renewable energies, there are also, of course, the needs related to the development of the automobile fleet, whose transition to electric power is just beginning.

Bearish copper speculators are hoping that the rebound that began in July draws a bearish flag and are probably strengthening their short positions on these levels:

This battle in the copper market, where the bears are watching for the inevitable deterioration in economic numbers and the bulls are watching the depletion of inventories, is also taking place in other metals.

As I explained in my last special mining bulletin, tin is also affected by this phenomenon.

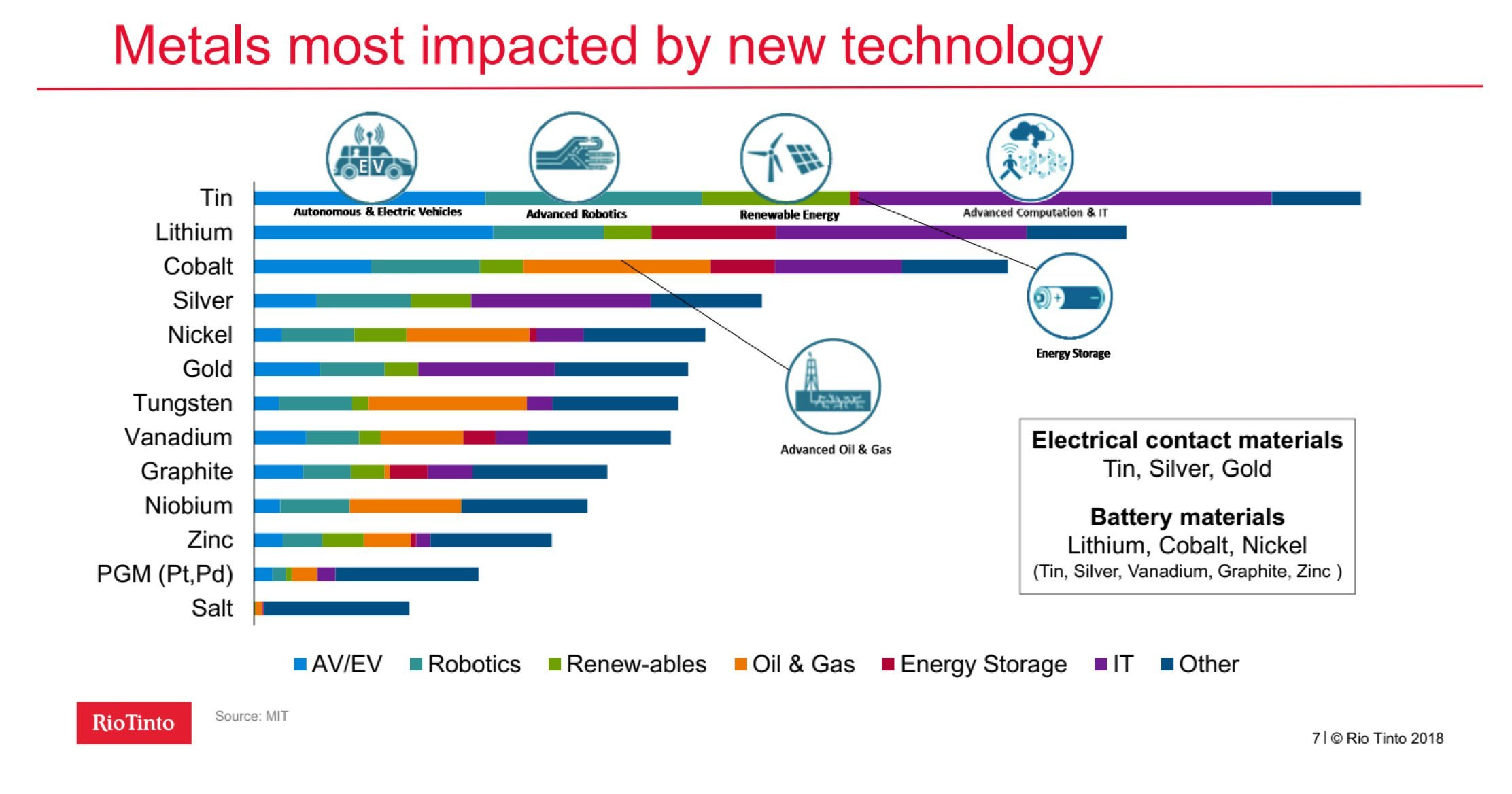

China is stockpiling tin on a massive scale, as is the United States. It must be said that this is the metal whose use will increase the most with the energy transition:

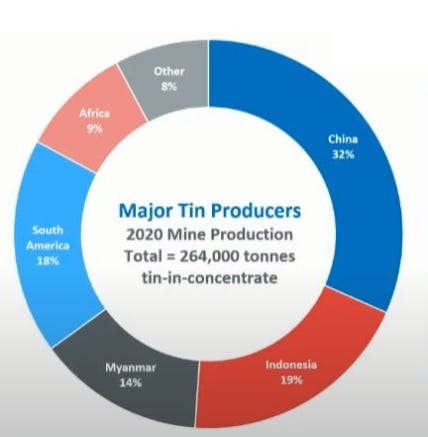

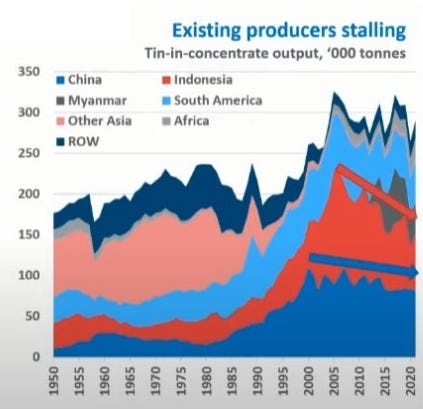

China and Indonesia supply half of the 300,000 tons produced each year (source International Tin Association):

Indonesia has just tightened its export conditions and production there has been in continuous decline since 2005. Chinese production is also drying up.

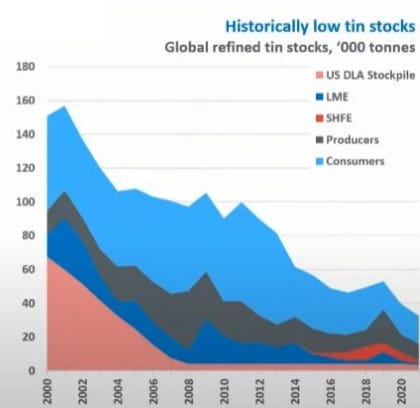

Tin needs will explode while inventories are decreasing. It is easy to understand the rush of countries to buy this strategic metal. As a result, inventories are at an all-time low:

Another market affected by this risk of shortages is the silver market. Here too, inventories are approaching historic lows.

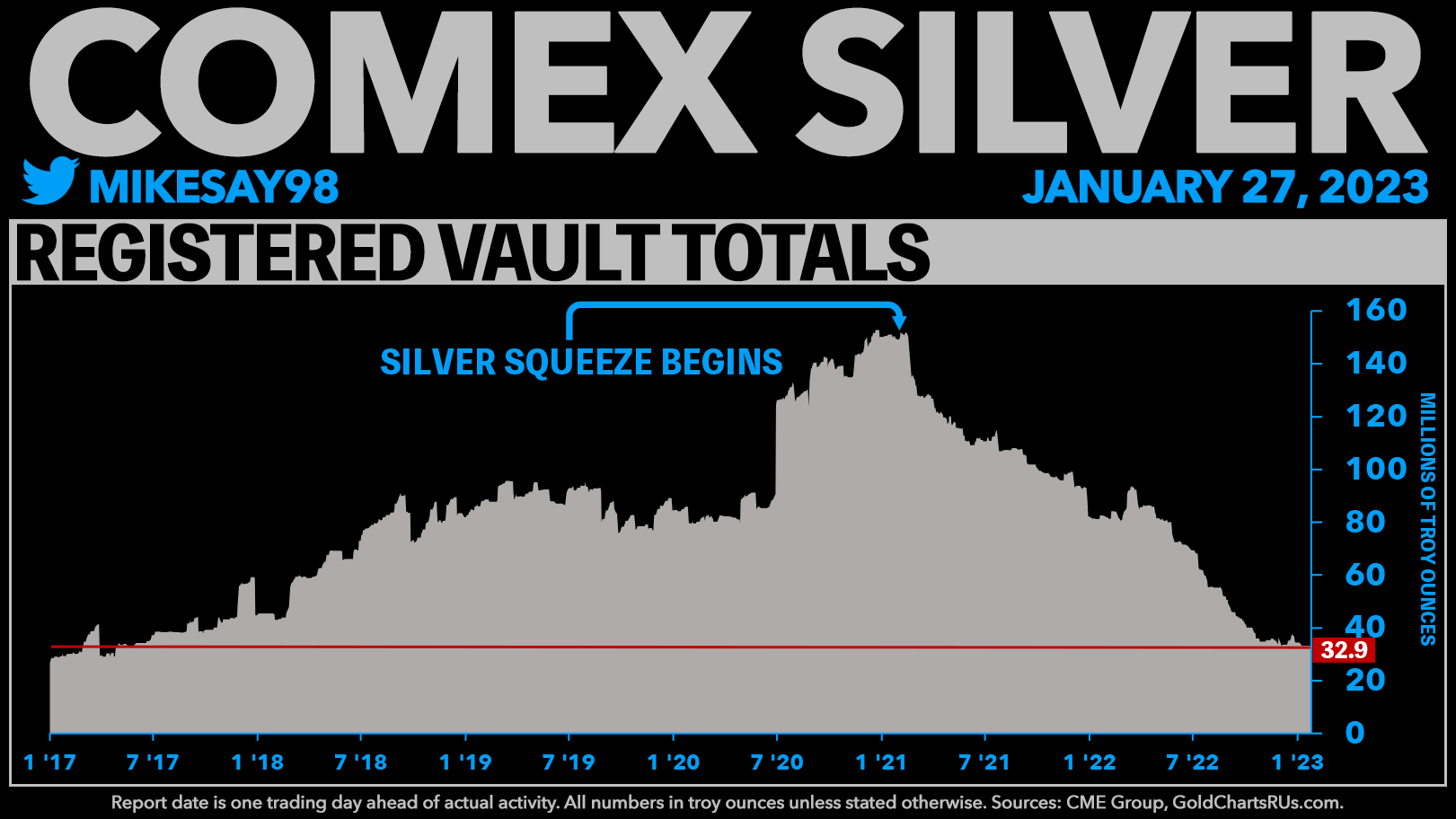

Michael Silversqueeze, whose weekly reports we follow, informs that silver inventories are at their lowest since 2017:

There are less than 33 million ounces of silver left in the COMEX vaults. Of that 33 million ounces, there are probably far fewer that are available quickly to meet futures deliveries.

According to the analyst Ronan Manly, the amount of silver available on the COMEX is much lower than expected, as 50% of the "eligible" would not be available.

The situation on the available inventories in Shanghai is also tense. The latest figures show a stockpile of 70 million ounces, or just over 2,100 tons of silver available.

In April 2020 and February 2021, the CME and CFTC exchanged correspondence regarding the delivery of gold and silver futures contracts. These letters stated that 50% of the eligible gold in COMEX-approved vaults in New York was not to be counted as deliverable supply, as these bars were held by long-term investors. In February 2021, the CME revealed that the situation was the same in the silver market. In other words, the COMEX silver inventory is actually twice as low as reported!

On November 18, an article from Reuters confirmed what we have been saying for several months: silver is about to enter a period of chronic deficit.

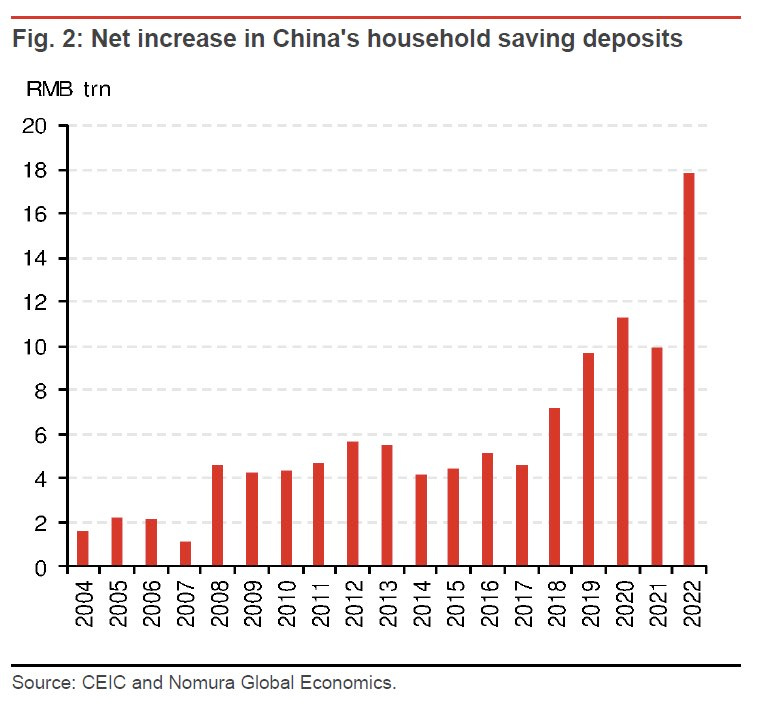

Silver inventories are dwindling, at a time when the saving capacity of Chinese households is rising sharply following the lockdowns caused by the health crisis:

It would only take a very small portion of these savings to be invested in silver to cause available inventory levels in China to fall to historically low levels as well.

In Western countries, buying physical silver is not always seen as a way to protect one's wealth, unlike in India or China, where gold and silver play a safe haven role when fears about the economy and real estate yields resurface, as is currently the case in Asia.

These considerations on silver inventories are far from worrying the bears on the metal's prices, who took advantage of an invalidation of the bullish flag breakout to strengthen their bearish positions:

The hourly chart shows that silver's failure to regain the bullish momentum it began in early November has led many speculators to play a short-term price correction:

Until the last ounce of silver in storage in London or Shanghai is exhausted, there will probably always be speculators in futures, even if the risk of a short squeeze increases as inventories decrease.

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.