European industry is facing a shock like nothing it has seen in the last 50 years. As stated in these articles last spring, the hike in prices that is being felt on the ground is of phenomenal magnitude.

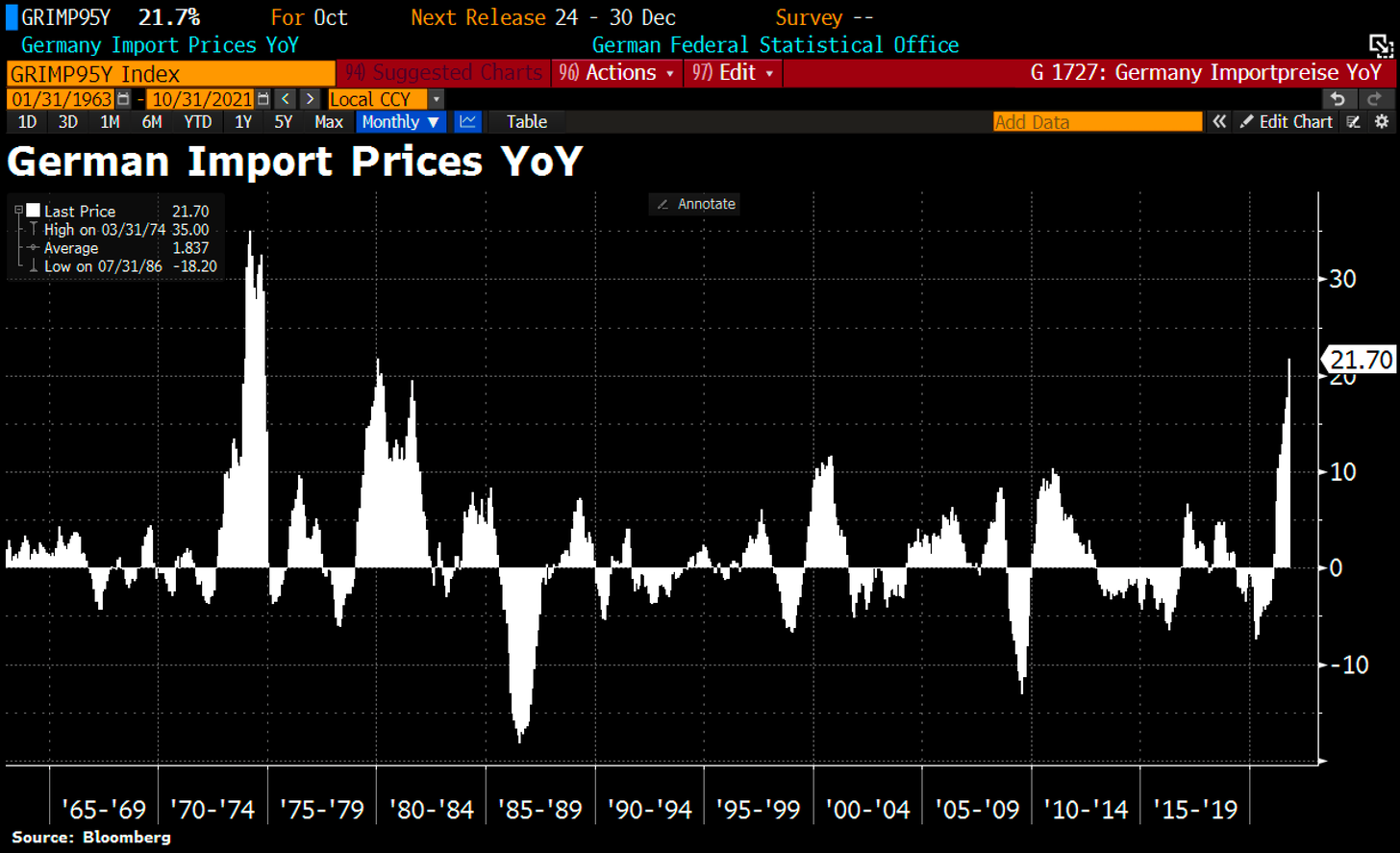

In Germany, the prices of imported goods are up by more than 20% compared to last year:

In Italy, the PPI index published at the start of the week exploded by 25.3% on the year, up 7.1% compared to last month...that corresponds to an annual growth rate of +128%!

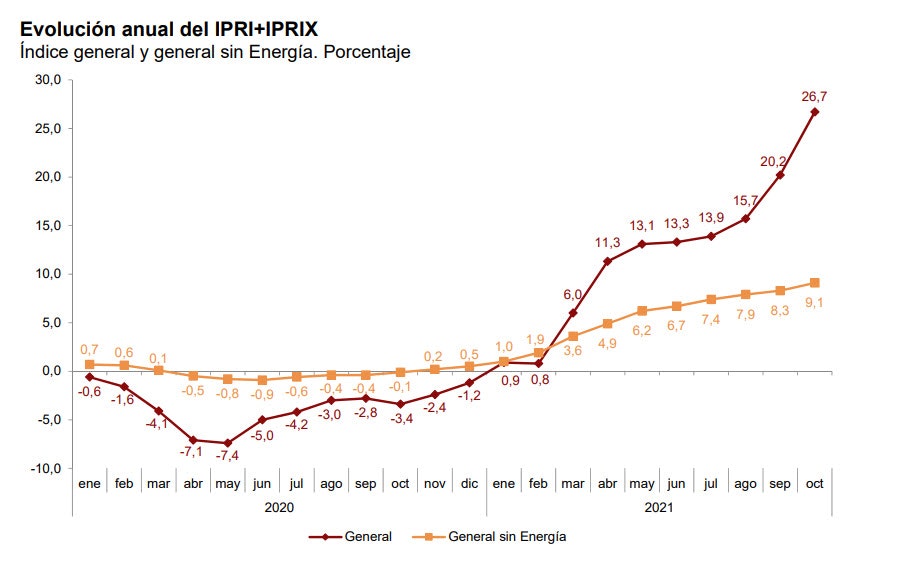

In Spain, energy prices are up 9.1% by comparison with last year, but it is the industrial prices index (the sum of import and export prices) that literally took off in October, hitting 26.7%.

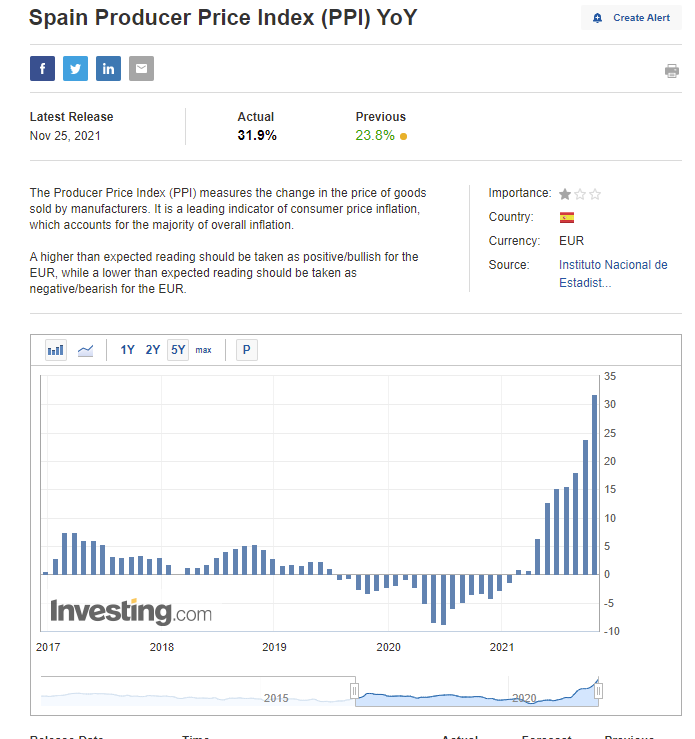

The PPI index has soared to 31.9% in the country:

The question that is now being asked in Europe is this: how are the industrial firms going to pass such a hike in prices onto the consumer, without bringing down on themselves the wrath of governments, who will undoubtedly make these same firms carry the blame for this hike?

These behaviors are very much a classic phenomenon in a phase of massive inflation. The next stage of the inflationary cycle that we are currently traversing will involve efforts to control the prices by the authorities, which will logically trigger even more pronounced shortages in a production chain that is already greatly weakened by the sanitary crisis and by the rise in transport and energy costs.

This type of intervention generally leads to a hyperinflationary risk (establishment of a parallel market, loss of confidence in the official prices, loss of confidence in the official currency). Let us hope that at this stage, where the European currency is really coming under pressure, the European authorities do not choose this path. Any attempt to control prices, by forcing producers to bear the burden of inflation alone, gets reflected in the level of the currency. We have had numerous examples in the past, notably in South America or in Africa, and just recently in Turkey.

The defense of the euro and the raising of interest rates ought, on the contrary, to be discussed by the European currency authorities as a matter of urgency. The inflationary shock that we are undergoing necessitates strong action on the part of the central bankers.

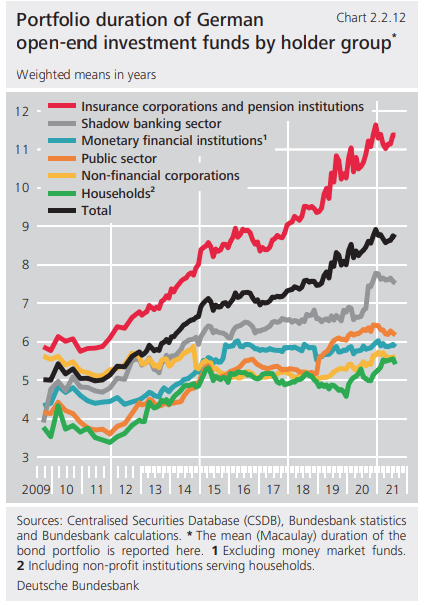

Regrettably, the ECB is faced with a situation that is far more delicate than 10 years ago. Its monetary policy has forced all the managers to increase the duration and risk of their bonds portfolio. Let’s take a look at the average duration of portfolios held in the German finance sector, the largest in Europe:

The average duration has risen, overall, by 5 years in barely 10 years, driven by an ever more intense quest for yields on the part of the portfolio managers. Today, any rise in the rates would therefore be a lot more painful for these portfolios, precisely because of the increase in the duration. Moreover, the ECB’s asset purchases have made the collateral of these bonds products deteriorate. This increases the risk of a loss of real-terms capital, insofar as a rapid hike in the rates would lead to an accelerated sale of these products.

The ECB faces an enormous dilemma: either it protects these portfolios, by refusing to act on the rates to counter inflation, or it takes urgent action on the rates to limit the stagflation and its impoverishing effects on the middle classes in Europe. The coming weeks will reveal to us which of these options it has chosen.

For the time being, the ECB still has its foot on the gas and is continuing to make the money printing machines work at full capacity. Its balance sheet is still growing in the same overwhelming manner:

TAPER WHAT? #ECB balance sheet keeps rising despite rampant inflation. Total assets have risen by another €14.7bn in the past week to hit fresh ATH at €8,457bn. ECB balance sheet now equal to 81.2% of Eurozone GDP vs Fed's 37.4%, BoE's 42%, BoJ's 134.6%. pic.twitter.com/SfkhW4jc5n

— Holger Zschaepitz (@Schuldensuehner) December 1, 2021

At this stage, the tangible signs of the comeback of inflation are very clear. In Europe, the fall in the euro and the energy crisis are aggravating factors.

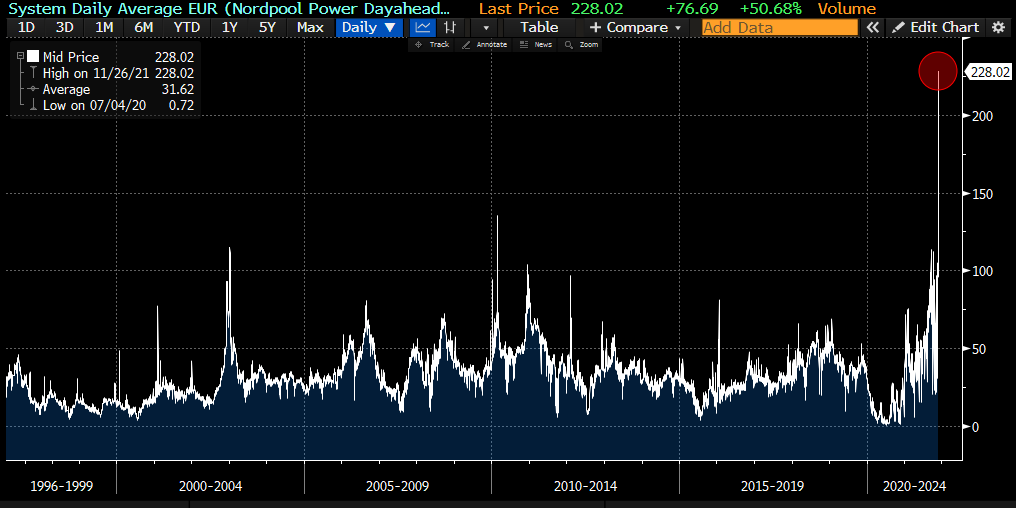

The Nordpool index, which measures the variation in the price of electricity in Europe, reached an all-time high of €228 per MWh last week!

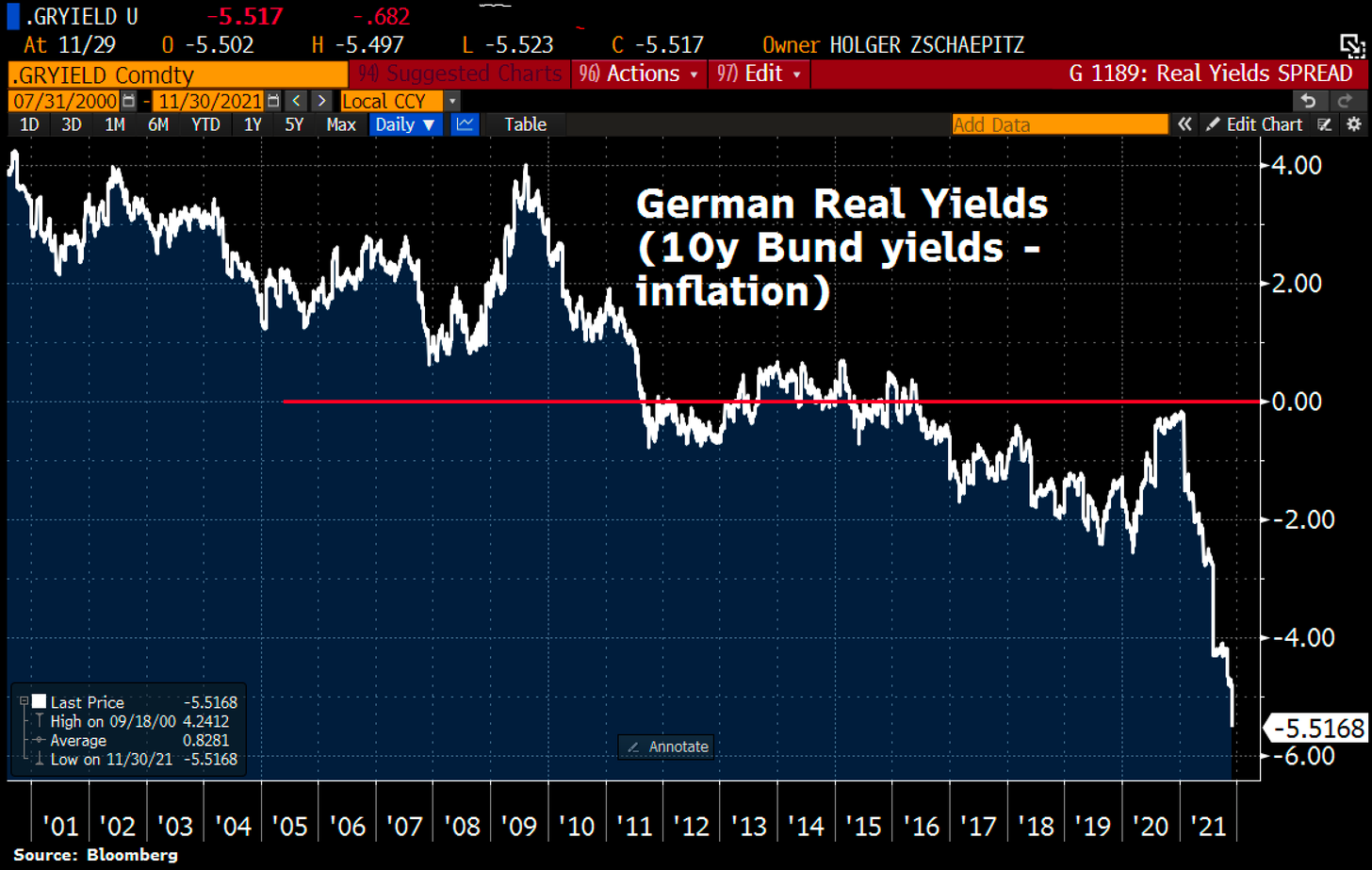

Not to take action on the rates today would mean leaving the single currency to bear the burden of this shock on its own, at a time when the real yields are collapsing, amplifying the risks of a loss of capital in this asset department:

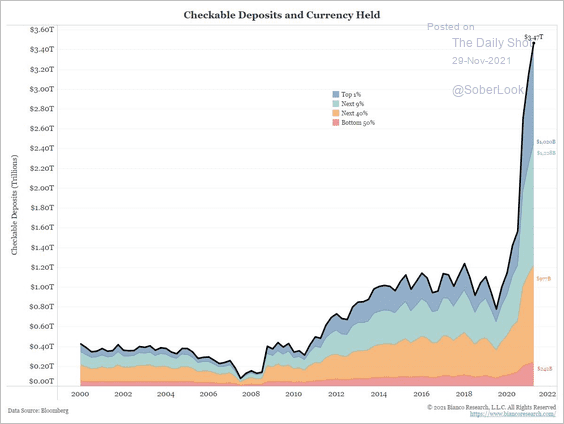

This risk of a loss of capital is appearing at a moment when the checkable deposits of wealthy households are reaching new highs. In the last two years, the amount of money that the affluent classes are setting aside has exploded.

This is even more true in the United States, where the reserves of the wealthiest are at an all-time high:

Never before have the rich accumulated so much in savings. The value of this cash, however, is in the process of being gnawed away at by inflation, at a rate that is even more spectacular in Europe.

The inflation is making a large portion of the middle class plunge into poverty. For the richest, the inflation is self-fueling the cycle of price hikes.

In this context and for this category of the population, the inflation is leading to spending, and this is driving the prices upwards, resulting in a rise in salaries...and when salaries go up, income goes up in turn, generating new spending. We have now plunged into a lasting cycle of inflation, and a growing number of economists appear (at last) to have realized this.

Faced with the risk of a devaluation of the currencies, an increasing number of central banks in Europe are stepping up their purchases of gold.

After China, Russia and India… new countries are being added to the list.

For the first time in 20 years, Singapore increased its gold reserves by 20% this year, as part of a movement that went largely unnoticed.

The Central Bank of Ireland purchased 1 extra tonne of gold in October. The net purchases since the start of the year have risen to just over 2 tonnes, taking the global gold reserves to 8 tonnes.

This accumulating of gold by the central banks is now being accompanied by requests for gold reserves held abroad to be repatriated. After Germany, it is now the turn of Serbia to act: the country decided to urgently repatriate 37 tonnes of gold that it was storing in Switzerland. Serbia’s central bank is participating in a general movement aimed at securing ‘allocated’ accounts, which, if it continues, risks posing a real problem for the ‘unallocated’ architecture of the metals accounts at several financial establishments.

At the same time and as part of the same process, the nations that produce metals are becoming very protective of their resources. Chile and Mexico are planning to increase the taxes on mining, while Indonesia is considering an outright ban on all exports of tin, forcing its customers to open metal refineries on their own soil. The time of ‘paper’ investment on commodities is coming to an end; investors are now looking for genuine exposure on tangible assets and on the players who actually have their hands on the material!

If one steps back to take a more long-term view of the gold prices, one sees that gold is still trapped between $1760 and $1800, in that famous consolidation triangle initiated in 2020. The bearish speculators on gold have succeeded in containing the latest breakout, and since then, we have gone back down onto the bullish trend line initiated in 2018:

To finish with, a brief look back at the markets: the Crab harmonious pattern detected on the Nasdaq (see this article) has certainly given a bearish signal whose first target has still not been reached:

Even if the end of the year logically means that the markets will be kept high off the ground for the recording of annual performances, on the charts, the bearish target has still not been reached and the short pressure on the indices remains present on the latest tops.

Original source: RechercheBay

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.