Let us turn our spotlight this week on Europe, and on Germany especially.

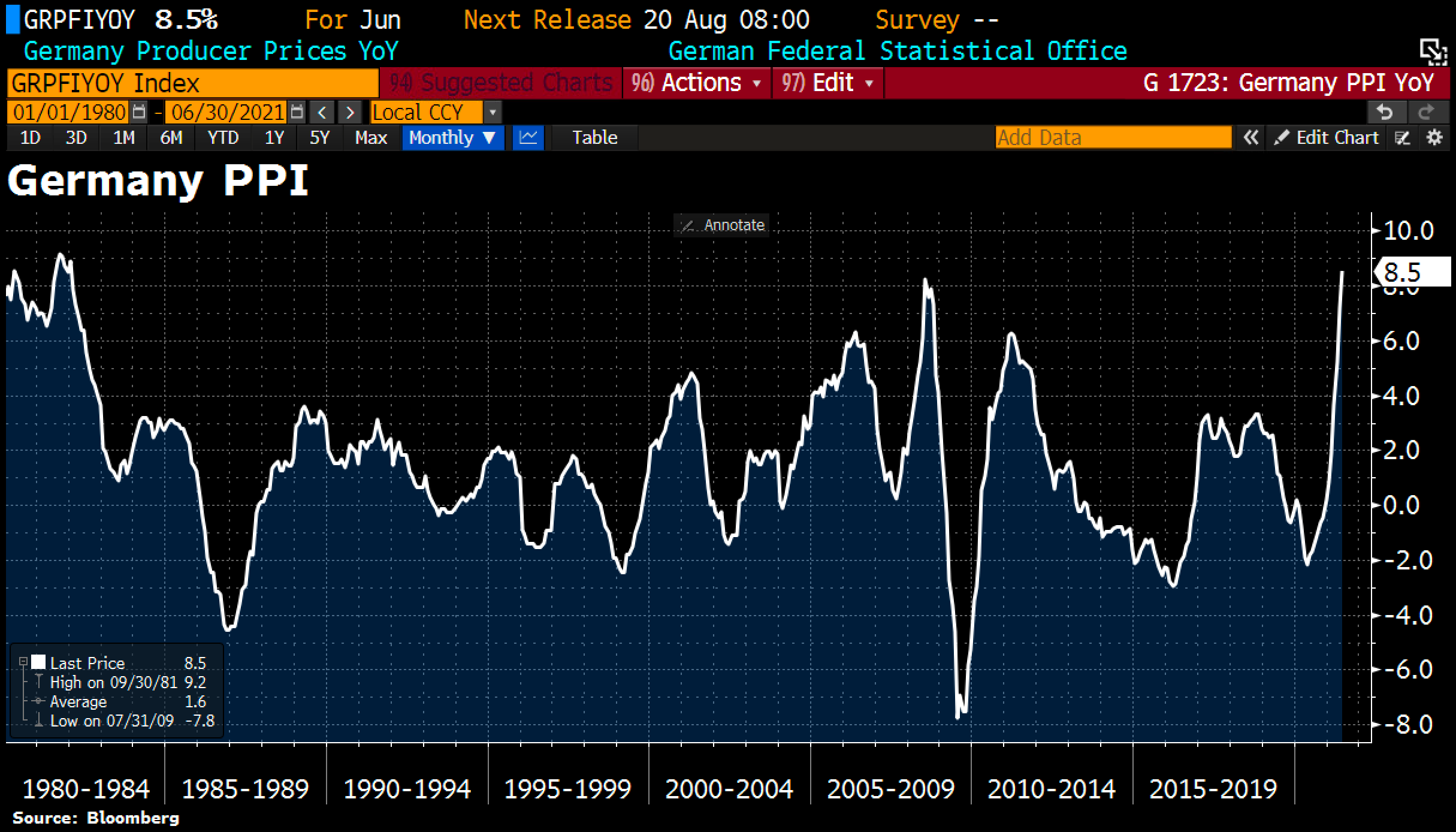

As announced in our previous articles, inflation is slowly but surely spreading towards ‘the Old Continent’. The latest figure for Germany’s PPI index has reached heights not seen since the 1980s:

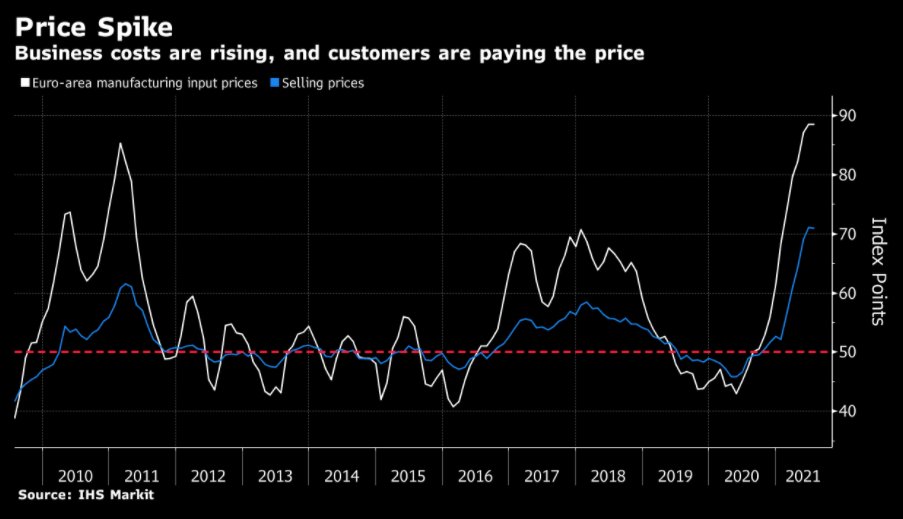

Up until now, the inflation was invisible to the European consumer, for it had been contained in commodities, but was not yet present in the prices at consumption level. Now, the inflation is being reflected in the rise in manufacturing prices, and this rise is then being transferred to the price of goods paid by the consumer.

This inflation is already having consequences on economic activity.

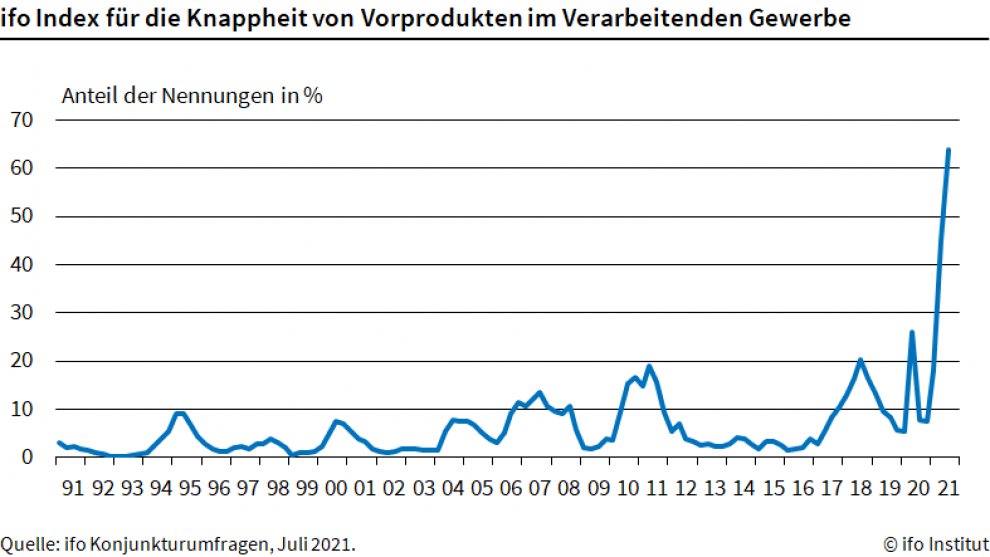

The IFO reports that, due to a rise in the prices of commodities and problems with logistics, more than 60% of German industry is starting to complain about bottlenecks that are affecting their production. It is a veritable industrial shock, as the chart below shows:

Index of the scarcity of intermediary goods in the manufacturing sector

Even if the authorities are hoping that these shortages and supply times will remain transitory, their effects are further sustaining the rise in prices. As anyone who works in the retail sector will tell you, any delay in supply necessitates an increase in tariffs, in order to absorb the reduction in the margin brought about by a shortage, for too long a period, of an essential industrial component. The calculations for offers must now factor in these delays and be refined as a result, so as to absorb this fresh uncertainty connected to the bottlenecks. It is our hope that the bottlenecks will be transitory, but the inflation certainly won’t be.

The economy cannot be rebooted in the same way that one would carry out a simple software reboot. This is another thing that the economists, hooked on their models and comfortably ensconced behind their screens during lockdown, failed to see coming.

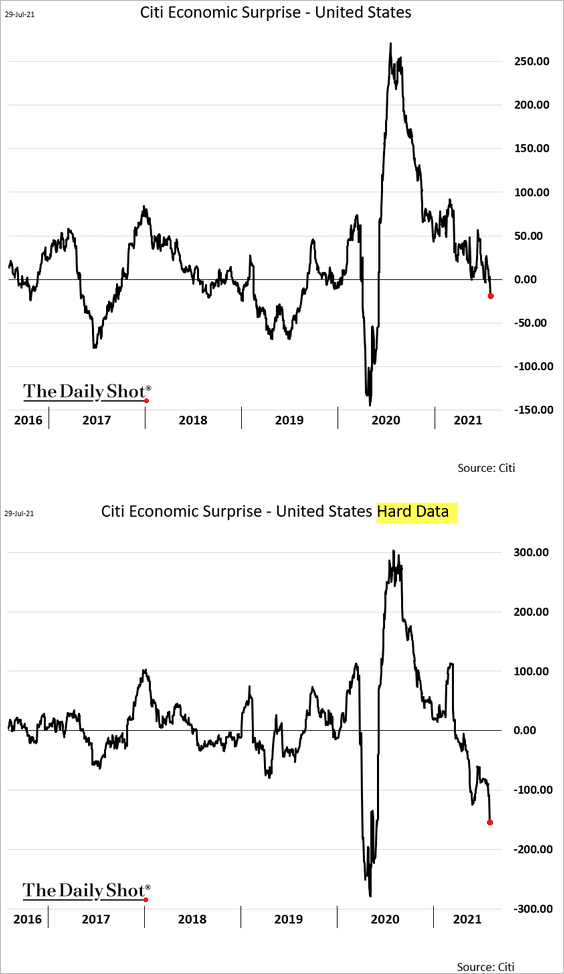

There is even a risk that the real economy might seize up, for the comeback of inflation is beginning to break the production chains. In the United States, some indicators are starting to fall again. Gross Domestic Product is not as high as expected this quarter. Above all, it was the Economic Surprise Index, published by Citi, that cooled observers’ expectations:

The markets continue to be bolstered by the hope of a new fiscal plan from the Biden administration.

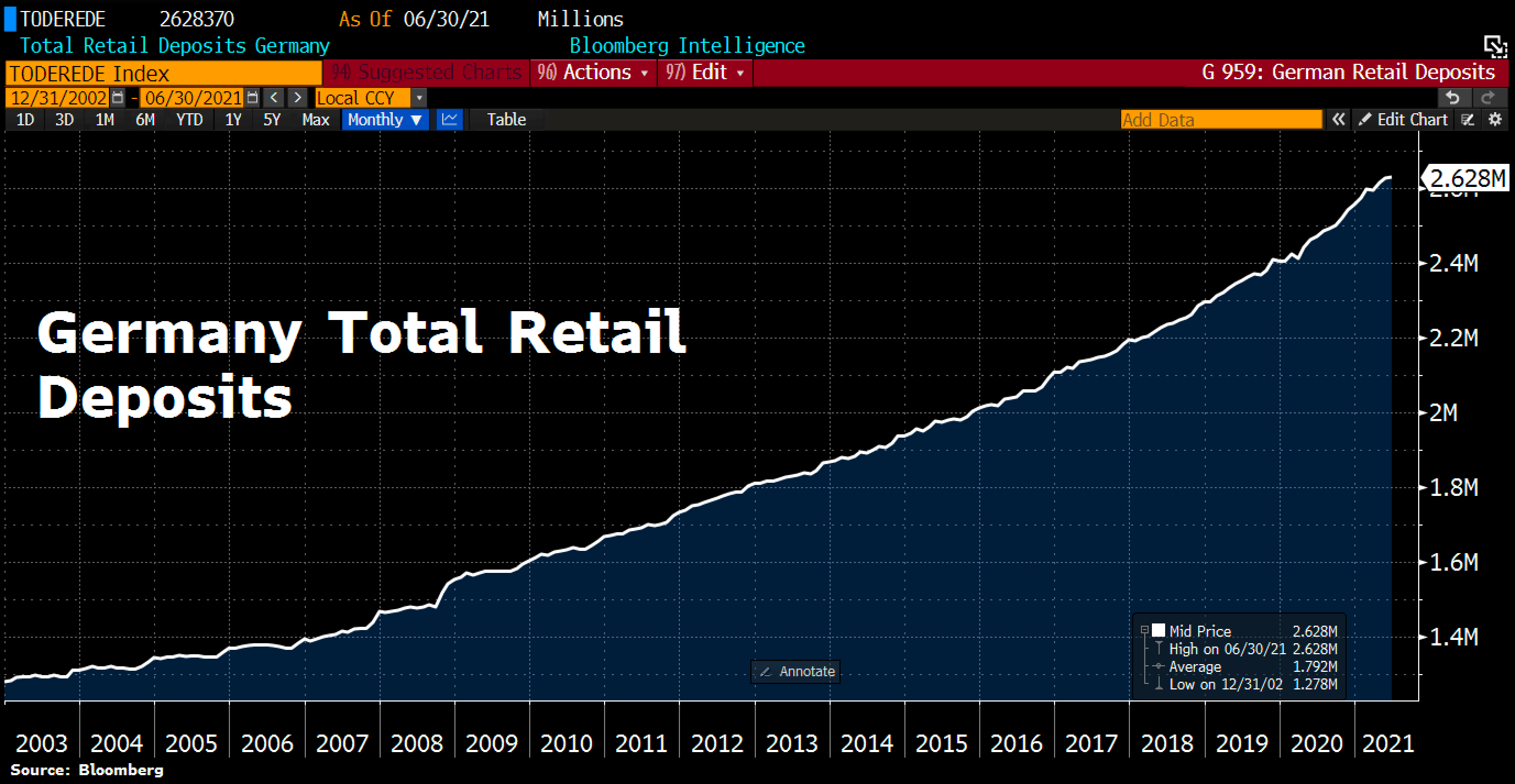

But anxiety is returning in Europe, and this is translating into a new deposits record in Germany.

The Germans are continuing to accumulate savings, with their combined deposits reaching an all-time high of 2.63 trillion euros this week!

Knowing as we do that the German banks are now charging increasingly sizeable commission on these deposits (most commonly in the form of negative interest) and that annual inflation is currently at almost 4%, the net cumulative loss for these German savings must now be in the hundreds of billions.

This cash rush is costing dear, but the bond investments are also beginning to cost their owners a fortune.

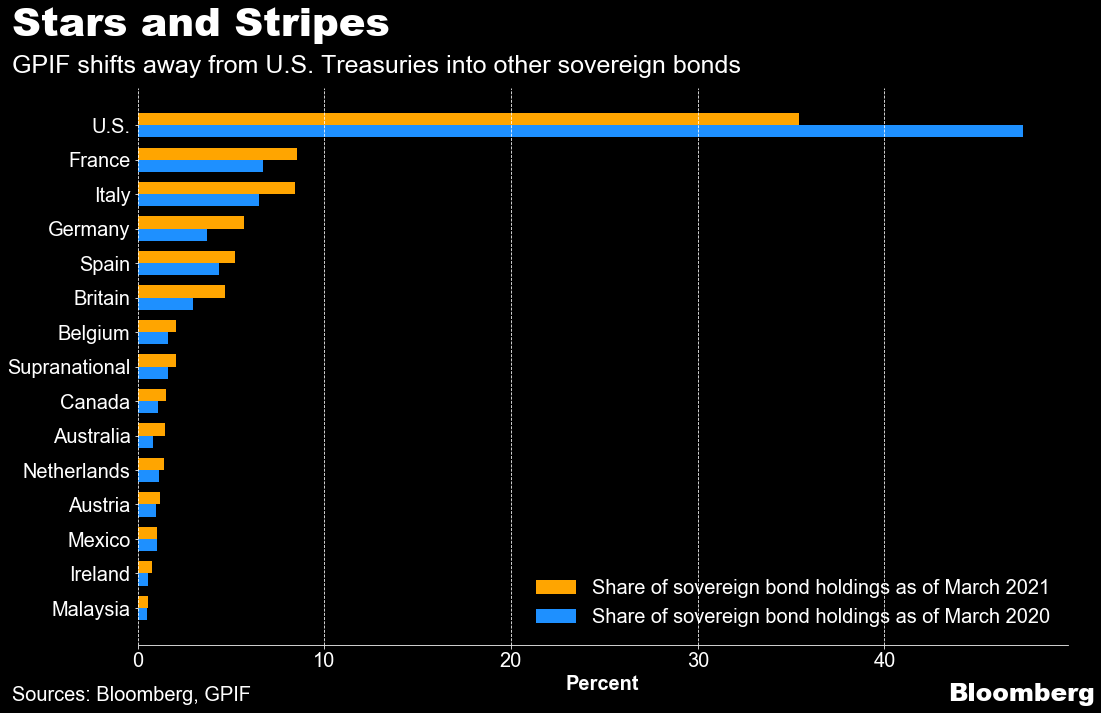

In this rush towards cash, it stands to reason that we are seeing high demand for treasury bonds in Europe. This demand is sustained in the retail sector, but it is also being driven by the institutions, which are changing their strategies and starting to come back to the Euro zone. This is the case for the Japanese fund GPIF, which manages the country’s pensions on the government’s behalf. Bloomberg informs us that this fund has significantly increased its bond investments in Europe.

The primary cause of this sudden appetite in Europe, however, is the fact that it has been unleashed from the U.S. bonds market. Last year, U.S. bonds constituted half of the portfolio of foreign bonds. The fund reduced its exposure to 35% in just a few months, underlining the de-dollarization movement by institutions and central banks all over the world. Russia made the news last month by announcing the complete “de-dollarization” of its exchanges. Seeing the largest Japanese fund reduce its exposure to the dollar, today, is even more significant. Even if this only affects some 100 billion liquidated bonds, it confirms there is a movement that is spreading to Asia. It is a real alarm bell for the greenback. The activity of the U.S. monetary printing press is starting to have consequences: the more money the Fed prints, the more it puts off the buyers of the U.S. debt... prompting the Fed to do even more printing, to fill a demand that is disappearing... thereby weakening the next round of auctions, and exporting even more inflation to its trading partners. Even though the dollar is still the currency of international exchanges, the U.S. currency risks going back to a less central role in a world that is becoming increasingly multi-polar. The dollar is therefore at risk of having to abandon its privileged status; it will therefore be unable to escape the classic rule whereby investors turn their backs on the currency issued by a country whose central bank is doing too much printing.

The demand for bonds in Europe has also had an impact on the strengthening of the market for private debt, a consequence of this strong demand. Today, there are almost 2 trillion euros’ worth of private negative-yield European bonds. That is more than half of the entire private bond section of the market. We have returned to the absurdly low valuation levels seen in 2016.

Savers are losing the economies they have made on their cash assets, and they are also losing on their bond assets.

This time around, the ECB doesn’t even need to do anything to reduce the rates. The European bonds market is currently benefiting from the distrust in the U.S. market, because inflation there is (for the time being) higher!

Admittedly, what is happening in the United States is fairly jaw-dropping and has taken all of the Fed’s economists by surprise (it is fair to say that their surprise at each new shock is no longer surprising!).

Each week, the price of a commodity literally soars. This week, it was the turn of hot-rolled coil steel, an essential industrial component:

As far as agricultural commodities are concerned, potash barge has gone from $190 to $550 in a year, an increase of exactly $1 a day. One does not need to be an expert on agriculture to imagine what this rise signifies for the global agricultural industry. The repercussions for food prices may well be significant - as early as in the fall.

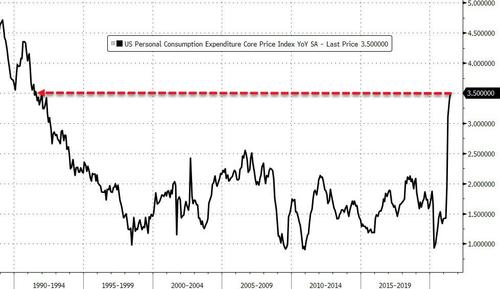

On the statistical front, the latest index measuring inflation (published last week) is one of the tools most closely watched by the monetary authorities in order to identify variations in inflation. It is the PCE index, which, to be more precise, measures sentiment about this inflation at the level of the consumer:

The rise in this index is vertiginous. In just a few months, the index has returned to the heights it reached in the early 1990s.

This skyrocketing of inflation is a threat to the yield from the bond market.

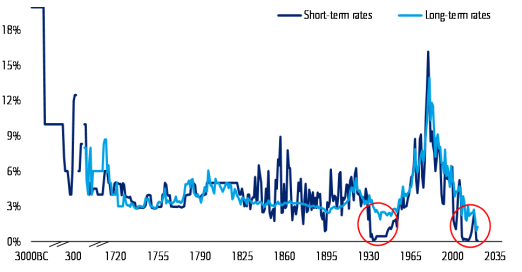

Bank of America has calculated that global output is at its lowest for 5000 years...

To put it plainly, the bonds market has never yielded so little, at a time when inflation has never been so high. The fact that this market has never been so big is an even more problematic issue.

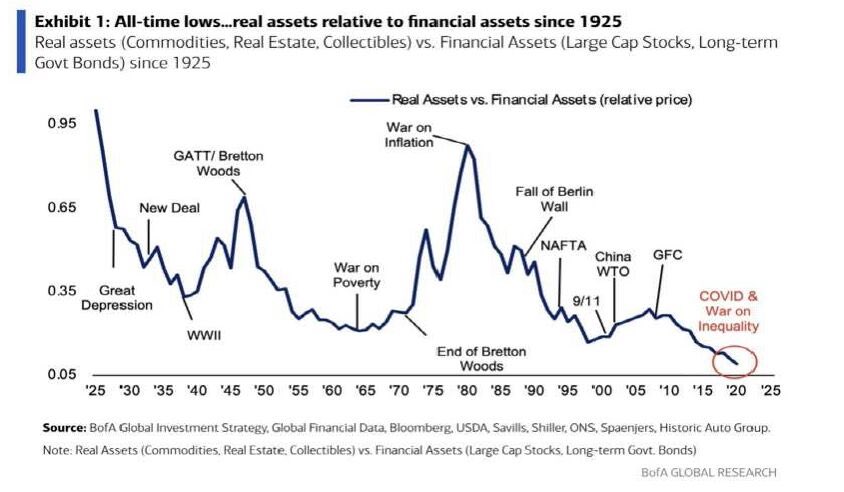

In the same report, the U.S. bank measured the ratio between financial assets (bonds and the stocks of major companies) and tangible investments. There, too, the chart is striking. The financial assets are at an all-time high price in relation to the prices of tangible assets:

In these tangible assets, real estate and collectibles are already at stratospheric levels.

Right now, it comes as no surprise to see a rotation taking place from financial assets to commodities. This is precisely what is happening before our very eyes, and it explains these vertiginous rises from one week to the next. The rises are affecting cereal crops, and next it will be the turn of industrial materials. Each week, a commodity skyrockets. The corrections that follow are violent, and then they get even worse; it’s the sign of an era of speculation that could be very dangerous for the price of food, but is also a classic phenomenon in a movement of uncontrolled inflation.

Gold and silver are still assets that are under the control of the paper futures market. Their price is linked to a financial asset that is completely under control. The true price of gold and silver will be the one that is displayed after the shift from paper to physical. The current price reflects precisely the preponderance of the financial market over the market for real assets. But for how long? Most of those who hold gold and silver are not directly exposed to physical. They think they have gold, when in fact they possess certificates or futures that are no more than a different form of financial asset, which has nothing to do with the physical product per se.

It stands to reason that the rotation from financial assets to real assets will be accompanied by a shift from paper gold assets to physical ones. The problem? There are a lot more financial “paper gold” / “paper silver” assets than real “physical gold” / “physical silver” assets available.

This shift from financial assets to real assets has already begun:

For gold: the movement has been initiated by the central banks which are repatriating physical gold into their vaults…

For silver: since the launch of the SilverShort Squeeze, retail has literally been drying up the physical market for this metal and forcing the bullion banks to cover their short positions on the COMEX.

The view among the observers of this market is unanimous: in this rotation from financial assets to tangible ones, all those who own “paper” precious metals will be unable to transfer their assets to physical ones. In this game of musical chairs, there are bound to be some losers.

Original source: Recherche Bay

Reproduction, in whole or in part, is authorized as long as it includes all the text hyperlinks and a link back to the original source.

The information contained in this article is for information purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or a recommendation to buy or sell.